Belarus Uprising: How a Dictator Became Vulnerable Lucan Ahmad Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romanian Political Science Review Vol. XXI, No. 1 2021

Romanian Political Science Review vol. XXI, no. 1 2021 The end of the Cold War, and the extinction of communism both as an ideology and a practice of government, not only have made possible an unparalleled experiment in building a democratic order in Central and Eastern Europe, but have opened up a most extraordinary intellectual opportunity: to understand, compare and eventually appraise what had previously been neither understandable nor comparable. Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review was established in the realization that the problems and concerns of both new and old democracies are beginning to converge. The journal fosters the work of the first generations of Romanian political scientists permeated by a sense of critical engagement with European and American intellectual and political traditions that inspired and explained the modern notions of democracy, pluralism, political liberty, individual freedom, and civil rights. Believing that ideas do matter, the Editors share a common commitment as intellectuals and scholars to try to shed light on the major political problems facing Romania, a country that has recently undergone unprecedented political and social changes. They think of Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review as a challenge and a mandate to be involved in scholarly issues of fundamental importance, related not only to the democratization of Romanian polity and politics, to the “great transformation” that is taking place in Central and Eastern Europe, but also to the make-over of the assumptions and prospects of their discipline. They hope to be joined in by those scholars in other countries who feel that the demise of communism calls for a new political science able to reassess the very foundations of democratic ideals and procedures. -

Global Human Rights

FINANCIAL REPORTING AUTHORITY (CAYFIN) Delivery Address: th Mailing Address: 133 Elgin Ave, 4 Floor P.O. Box 1054 Government Administrative Building Grand Cayman KY1-1102 Grand Cayman CAYMAN ISLANDS CAYMAN ISLANDS Direct Tel No. (345) 244-2394 Tel No. (345) 945-6267 Fax No. (345) 945-6268 Email: [email protected] Financial Sanctions Notice 29/09/2020 Global Human Rights Introduction 1. The Global Human Rights Sanctions Regulations 2020 (S.I. 680/2020) (the Regulations) were made under the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (the Sanctions Act) and provide for the freezing of funds and economic resources of certain persons, entities or bodies responsible for or involved in serious violations of human rights. 2. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office have updated the UK Sanctions List on GOV.UK. This list includes details of all sanctions enacted under the Sanctions Act. A link to the UK Sanctions List can be found below. 3. Following the publication of the UK Sanctions List, information on the Consolidated List has been updated. Notice summary 4. 8 entries listed in the annex to this Notice have been added to the Consolidated List and are now subject to an asset freeze. 5. The identifying information for one individual has been updated and he remains subject to an asset freeze. What you must do 6. You must: i. check whether you maintain any accounts or hold any funds or economic resources for the persons set out in the Annex to this Notice; ii. freeze such accounts, and other funds or economic resources and any funds which are owned or controlled by persons set out in the Annex to the Notice; iii. -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Dear Delegates, Congratulations on Being Selected to the Kremlin, One of VMUN's Most Advanced Committees. My Name Is Harrison

Dear Delegates, Congratulations on being selected to the Kremlin, one of VMUN’s most advanced committees. My name is Harrison Ritchie, and I will be your director for this year’s conference. I have been involved in MUN since Grade 10, and have thoroughly enjoyed every conference that I have attended. This year’s Kremlin will be a historical crisis committee. In February, you will all be transported to the October of 1988, where you will be taking on the roles of prominent members of either the Soviet Politburo or Cabinet of Ministers. As powerful Soviet officials, you will be debating the fall of the Soviet Union, or, rather, how to keep the Union together in such a tumultuous time. In the Soviet Union’s twilight years, a ideological divide began to emerge within the upper levels of government. Two distinct blocs formed out of this divide: the hardliners, who wished to see a return to totalitarian Stalinist rule, and the reformers, who wished to progress to a more democratic Union. At VMUN, delegates will hold the power to change the course of history. By exacting your influence upon your peers, you will gain valuable allies and make dangerous enemies. There is no doubt that keeping the Union together will be no easy task, and there are many issues to address over the coming three days, but I hope that you will be thoroughly engrossed in the twilight years of one of the world’s greatest superpower and find VMUN an overall fulfilling experience. Good luck in your research, and as always, if you have any questions, feel free to contact me before the conference. -

L319 I Official Journal

Official Journal L 319 I of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Legislation 2 October 2020 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1387 of 2 October 2020 implementing Article 8a(1) of Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus . 1 DECISIONS ★ Council Implementing Decision (CFSP) 2020/1388 of 2 October 2020 implementing Decision 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Belarus . 13 Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. EN The titles of all other acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. 2.10.2020 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 319 I/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2020/1387 of 2 October 2020 implementing Article 8a(1) of Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 of 18 May 2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus (1), and in particular Article 8a(1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 18 May 2006, the Council adopted Regulation (EC) No 765/2006 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Belarus. (2) On 9 August 2020, Belarus conducted presidential elections, which were found to be inconsistent with international standards and marred by repression of independent candidates and a brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in the wake of the elections. -

En En Amendments 1

European Parliament 2019-2024 Committee on Foreign Affairs 2020/2081(INI) 2.9.2020 AMENDMENTS 1 - 388 Draft report Petras Auštrevičius (PE652.398v01-00) Proposal for a Recommendation to the Council, the Commission and the Vice- President of the Commission/High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy on relations with Belarus (2020/2081(INI)) AM\1212303EN.docx PE657.166v01-00 EN United in diversityEN AM_Com_NonLegReport PE657.166v01-00 2/171 AM\1212303EN.docx EN Amendment 1 Viola Von Cramon-Taubadel on behalf of the Greens/EFA Group Motion for a resolution Citation 2 Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Council — having regard to the Council conclusions on Belarus of 15 February conclusions on Belarus of 15 February 2016, 2016 and the main outcomes of the video conference of Foreign Affairs Ministers of 14 August 2020, Or. en Amendment 2 Viola Von Cramon-Taubadel on behalf of the Greens/EFA Group Motion for a resolution Citation 2 a (new) Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Conclusions by the President of the European Council following the video conference of the members of the European Council on 19 August 2020, Or. en Amendment 3 Attila Ara-Kovács Motion for a resolution Citation 4 Motion for a resolution Amendment — having regard to the Joint — having regard to the Joint Declarations of the Eastern Partnership Declarations of the Eastern Partnership Summits of 2009 in Prague, 2011 in Summits of 2009 in Prague, 2011 in Warsaw, 2013 in Vilnius, 2015 in Riga and Warsaw, 2013 in Vilnius, 2015 in Riga, 2017 in Brussels, 2017 in Brussels and Eastern Partnership leaders' video conference in 2020, AM\1212303EN.docx 3/171 PE657.166v01-00 EN Or. -

U-M·I University Microfilms International a Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road

Castro's Cuba and Stroessner's Paraguay: A comparison of the totalitarian/authoritarian taxonomy. Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Sondrol, Paul Charles. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 11:08:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185284 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photogr2,pb and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted.. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this -reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is inciuded in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Prospects for Democracy in Belarus

An Eastern Slavic Brotherhood: The Determinative Factors Affecting Democratic Development in Ukraine and Belarus Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi, B.A. Graduate Program in Slavic and East European Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Trevor Brown, Advisor Goldie Shabad Copyright by Nicholas Hendon Starvaggi 2009 Abstract Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, fifteen successor states emerged as independent nations that began transitions toward democratic governance and a market economy. These efforts have met with various levels of success. Three of these countries have since experienced “color revolutions,” which have been characterized by initial public demonstrations against the old order and a subsequent revision of the rules of the political game. In 2004-2005, these “color revolutions” were greeted by many international observers with optimism for these countries‟ progress toward democracy. In hindsight, however, the term itself needs to be assessed for its accuracy, as the political developments that followed seemed to regress away from democratic goals. In one of these countries, Ukraine, the Orange Revolution has brought about renewed hope in democracy, yet important obstacles remain. Belarus, Ukraine‟s northern neighbor, shares many structural similarities yet has not experienced a “color revolution.” Anti- governmental demonstrations in Minsk in 2006 were met with brutal force that spoiled the opposition‟s hopes of reenacting a similar political outcome to that which Ukraine‟s Orange Coalition was able to achieve in 2004. Through a comparative analysis of these two countries, it is found that the significant factors that prevented a “color revolution” in Belarus are a cohesive national identity that aligns with an authoritarian value system, a lack of engagement with U.S. -

Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past: a Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region

CBEES State of the Region Report 2020 Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region Published with support from the Foundation for Baltic and East European Studies (Östersjstiftelsen) Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past A Comparative Study on Memory Management in the Region December 2020 Publisher Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, CBEES, Sdertrn University © CBEES, Sdertrn University and the authors Editor Ninna Mrner Editorial Board Joakim Ekman, Florence Frhlig, David Gaunt, Tora Lane, Per Anders Rudling, Irina Sandomirskaja Layout Lena Fredriksson, Serpentin Media Proofreading Bridget Schaefer, Semantix Print Elanders Sverige AB ISBN 978-91-85139-12-5 4 Contents 7 Preface. A New Annual CBEES Publication, Ulla Manns and Joakim Ekman 9 Introduction. Constructions and Instrumentalization of the Past, David Gaunt and Tora Lane 15 Background. Eastern and Central Europe as a Region of Memory. Some Common Traits, Barbara Trnquist-Plewa ESSAYS 23 Victimhood and Building Identities on Past Suffering, Florence Frhlig 29 Image, Afterimage, Counter-Image: Communist Visuality without Communism, Irina Sandomirskaja 37 The Toxic Memory Politics in the Post-Soviet Caucasus, Thomas de Waal 45 The Flag Revolution. Understanding the Political Symbols of Belarus, Andrej Kotljarchuk 55 Institutes of Trauma Re-production in a Borderland: Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania, Per Anders Rudling COUNTRY BY COUNTRY 69 Germany. The Multi-Level Governance of Memory as a Policy Field, Jenny Wstenberg 80 Lithuania. Fractured and Contested Memory Regimes, Violeta Davoliūtė 87 Belarus. The Politics of Memory in Belarus: Narratives and Institutions, Aliaksei Lastouski 94 Ukraine. Memory Nodes Loaded with Potential to Mobilize People, Yuliya Yurchuk 106 Czech Republic. -

The EU and Belarus – a Relationship with Reservations Dr

BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION EDITED BY DR. HANS-GEORG WIECK AND STEPHAN MALERIUS VILNIUS 2011 UDK 327(476+4) Be-131 BELARUS AND THE EU: FROM ISOLATION TOWARDS COOPERATION Authors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Dr. Vitali Silitski, Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann, Andrei Yahorau, Dr. Svetlana Matskevich, Valeri Fadeev, Dr. Andrei Kazakevich, Dr. Mikhail Pastukhou, Leonid Kalitenya, Alexander Chubrik Editors: Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck, Stephan Malerius This is a joint publication of the Centre for European Studies and the Konrad- Adenauer-Stiftung. This publication has received funding from the European Parliament. Sole responsibility for facts or opinions expressed in this publication rests with the authors. The Centre for European Studies, the Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung and the European Parliament assume no responsibility either for the information contained in the publication or its subsequent use. ISBN 978-609-95320-1-1 © 2011, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin / Berlin © Front cover photo: Jan Brykczynski CONTENTS 5 | Consultancy PROJECT: BELARUS AND THE EU Dr. Hans-Georg Wieck 13 | BELARUS IN AN INTERnational CONTEXT Dr. Vitali Silitski 22 | THE EU and BELARUS – A Relationship WITH RESERvations Dr. Kai-Olaf Lang, Dr. Martin Koopmann 34 | CIVIL SOCIETY: AN analysis OF THE situation AND diRECTIONS FOR REFORM Andrei Yahorau 53 | Education IN BELARUS: REFORM AND COOPERation WITH THE EU Dr. Svetlana Matskevich 70 | State bodies, CONSTITUTIONAL REALITY AND FORMS OF RULE Valeri Fadeev 79 | JudiciaRY AND law -

Яюm I C R O S O F T W O R

Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) MASS MEDIA IN BELARUS 2004 ANNUAL REPORT Minsk 2005 C O N T E N T S INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW /2 STATISTICAL BACKGROUND /3 CHANGES IN THE LEGISLATION /5 INFRINGEMENTS OF RIGHTS OF MASS-MEDIA AND JOURNALISTS, CONFLICTS IN THE SPHERE OF MASS-MEDIA Criminal cases for publications in mass-media /13 Encroachments on journalists and media /16 Termination or suspension of mass-media by authorities /21 Detentions of journalists, summoning journalists to law enforcement bodies. Warnings of the Office of Public Prosecutor /29 Censorship. Interference in professional independence of editions /35 Infringements related to access to information (refusals in granting information, restrictive use of institute of accreditation) /40 The conflicts related to reception and dissemination of foreign information or activity of foreign mass-media /47 Economic policy in the sphere of mass-media /53 Restriction of the right on founding mass-media /57 Interference with production of mass-media /59 Hindrance to distribution of mass-media production /62 SENSATIONAL CASES The most significant litigations with participation of mass-media and journalists /70 Dmitry Zavadsky's case /79 Belarusian periodic printed editions mentioned in the monitoring /81 1 INFRINGEMENTS OF FREEDOM OF MASS INFORMATION IN BELARUS IN 2004. REVIEW The year 2004 for Belarus was the year of parliamentary elections and the referendum. As usual during significant political campaigns, the pressure on mass-media has increased in 2004. The deterioration of the media situation was not a temporary deviation after which everything usually comes back to normal, but represented strengthening of systematic and regular pressure upon mass- media, which continued after the election campaign. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

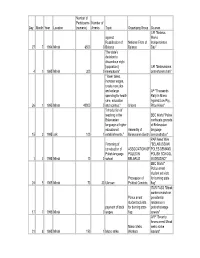

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with