Reluctant Gangsters: Youth Gangs in Waltham Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E Guide the Travel Guide with Its Own Website

Londonwww.elondon.dk.com e guide the travel guide with its own website always up-to-date d what’s happening now London e guide In style • In the know • Online www.elondon.dk.com Produced by Blue Island Publishing Contributors Jonathan Cox, Michael Ellis, Andrew Humphreys, Lisa Ritchie Photographer Max Alexander Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound in Singapore by Tien Wah Press First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Dorling Kindersley Limited 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL Reprinted with revisions 2006 Copyright © 2005, 2006 Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 4053 1401 X ISBN 978 1 40531 401 5 The information in this e>>guide is checked annually. This guide is supported by a dedicated website which provides the very latest information for visitors to London; please see pages 6–7 for the web address and password. Some information, however, is liable to change, and the publishers cannot accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of this book, nor for any material on third party websites, and cannot guarantee that any website address in this book will be a suitable source of travel information. We value the views and suggestions of our readers very highly. Please write to: Publisher, DK Eyewitness Travel Guides, Dorling Kindersley, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, Great Britain. -

Happy Bollock Goblin!

Lady Ga-goyle kicks off the Halloween celebrations with a surprise visit to G-A-Y happy bollock goblin! QX_973_Cover.indd 2 29/10/2013 20:09 Killer Once upon a time there was an evil queen, but you know all about her – and have probably seen her in Soho – so this Halloween we’re going to go one better and look at queens that kill. Gays may be one of the most peace- queens loving minorities in the world, but, just like the straights, our community has had its fair share of twisted minds – and these guys take it much further than a poisoned apple! BY DARREN PALFREY Murderer of Gianni Versace -Andrew Cunanan The Milwaukee Cunanan shot and killed four men across Cannibal The Kansas Butcher America, with no known motive. And we – Jeffrey Dahmer – Bob Berdella could have forgiven a little bit of serial killing, but Cunanan’s Dharma started early, Now this was a twisted next move was the committing his first bitch - Berdella sexually murder of Gianni murder at 18 years abused, raped, tortured Versace. Crimes old, but graciously spared the world from and killed at least six gay against fashion are anymore of his bloodshed for nine years. men in the late 1980s. He unforgivable – But then… this sista went on the rampage. drugged his victims before end of! (Beneath He’d lure men to his house and drug them turning them into unwilling sex slaves; he the botox, before killing them by strangulation. Often tied them up, beat them, gave them electric Donatella he would sexually molest the corpse shocks and put burning chemicals in their was deeply and then eat it – wonder if they’ve got eyes. -

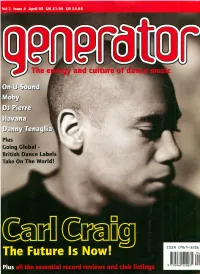

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head. -

Bloc South Further Submissions

BLOC SOUTH FURTHER SUBMISSIONS 1. Wayne Shires Witness Statement 2. Wayne Shires Exhibit 1 – East BLOC Premises liCenCe WS/01 3. Wayne Shires Exhibit 2 – The BloC Group Presentation WS/02 4. Wayne Shires Exhibit 3 – Letters of support WS/03 5. Wayne Shires Exhibit 4 – Letter of support from WS/04 Jonathan Simpson 6. Wayne Shires Exhibit 5 – Letter of support from Lord WS/05 Brian PaddiCk 7. Wayne Shires Exhibit 6 – Companies House ExtraCt WS/06 8. Wayne Shires Exhibit 7 – The Guardian Newspaper WS/07 ArtiCles 9. Wayne Shires Exhibit 8 – Revised proposed Conditions WS/08 10. Wayne Shires Exhibit 9 – Dispersal policy WS/09 11. Report prepared by Adrian Studd STATEMENT OF WAYNE SHIRES Proposed Operator of Bloc South Introduction 1. With the permission of Lambeth Council, I hope to open and operate a new nightclub and community premises to be called “Bloc South” in the railway arches at 65 Albert Embankment in Vauxhall. The club will be dedicated to serve the LGBTQ community in Lambeth and further afield. I am of course aware of the chequered history of this premises when it previously housed Club 65. 2. Within this statement I will set out : a. The reasons behind this application and my relationship with the previous operators; b. What I hope to achieve for the good of the LGBTQ community in Lambeth; c. The Bloc South concept and the operating hours required to make the project commercially viable; d. The steps I will take to ensure the licensing objectives are promoted and addressing issues raised by those who have made representations objecting to this application. -

Homo Floresiensis

Hobbit man Awesome Alps How to build a house Kings of the Hill How Homo floresiensis The Outdoor Club’s summer Imperial students visit The Cross Country Club start rewrites human history, page 3 expedition, page 10 El Salvador, page 12 their season, page 24 The student newspaper of Imperial College ● Established 1949 ● Issue 1304 ● Thursday 4 November 2004 ● www.felixonline.co.uk Ball boom Over 500 students attended a successful Freshers Ball last Varsity match to be expanded Friday. uNEWS page 2 Dangerous drinks “There still remains a lot of into festival of sport confusion and misinforma- tion about what happens in By Dave Edwards PHOTO: IAN GILLETT an attack and what happens Editor if you are unfortunate enough to have your drink spiked.” Next term’s Varsity match, u COMMENT page 6 already one of the most pres- tigious events in Imperial Eastern experience College sport, is set for expan- Felix Arts enjoys a feast of sion. Under new proposals, Russian music at the Royal eight matches will be played Festival Hall. in one day across three differ- uARTS page 18 ent sports to celebrate friend- ly rivalry, good sportsmanship Not Neverland and enjoyment of the game. “Suffice to say that the plot Since 2003, the annual was predictable and the Varsity match has seen characters were about as Imperial Medicals Rugby interesting as the Sherfield Football Club take on Building.” Imperial College Union Rugby uFILM page 19 Football Club for the JPR Williams Cup. The cup is Frisbee fun named after former Wales full Imperial College’s Ultimate back and St Mary’s old boy Frisbee team, the Disc John Peter Rhys Williams, Doctors, took part in a begin- who made 55 appearances for ners’ tournament in Hyde his country during a success- Park. -

An A-Z of Planning and Culture 2 3

1 AN A-Z OF PLANNING AND CULTURE 2 3 Copyright Contents Greater London Authority Page 4 Introduction Page 6 Challenges and opportunities for the capital October 2015 Page 9 Section 1: embedding culture within planning ISBN 978 1 84781 611 5 Page 10 From national to local plans Page 12 The London Plan Greater London Authority Page 14 The local plan Page 16 Planning frameworks City Hall, London SE1 2AA Page 18 The neighbourhood plan Page 20 Section 106 www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 Page 23 Section 2: working together to sustain culture minicom 020 7983 4458 Page 24 Asset of community value Page 27 Community ownership Page 28 Conservation area Written and researched by Page 30 Listed buildings The Mayor of London’s Culture and Planning teams Page 31 Special Policy Areas Page 32 Article 4 directions With thanks to London Councils, Historic England, London Borough Page 34 Agent of change of Camden, London Borough of Wandsworth, London Borough of Hackney, Page 36 On the horizon London Borough of Lambeth, Consolidated Developments Ltd, Transport Page 38 ‘Magnificent Seven’ for London, Friends of Stockwell Skatepark, RVT Future, Fortune Green and West Hampstead NDF, Antwerp Arms Association, TCPA, Bentley Priory Page 41 Section 3: case studies Museum, Cathedral Group PLC, Acme Studios. page 74 Further support and information page 76 Further reading Front cover: Gieves & Hawkes, Savile Row © GQ magazine / Conde Nast Back cover: Of Soil and Water, King’s Cross Pond Club designed by architects Ooze and artist Marjetica Potrč as part of the King’s Cross public art program RELAY © John Sturrock 4 5 Introduction The planning system plays a vital role in helping make sure we get the right balance. -

551-600 Redacted, Item 131. PDF 952 KB

From: To: Licensing Subject: Closure of Fabric Nightclub Date: 24 August 2016 14:04:06 Good afternoon, I am writing to you today to urge you to reconsider the closure of one of London's longest running and most legendary nightclubs which is Fabric. I am a regular clubgoer and I attend Fabric regularly and I can honestly say that the door security are very strict with searching you for illegal substances being bought into the club but obviously there is only a certain amount of body searching they can do before it becomes a case of them crossing the line which they could then get in trouble for. I am always thouroughly searched every single time I go. People will continue to take illegal substances and bring them to venues whether fabric is closed or not - this becomes the person taking the substance fault and not the venue who have done all they can to prevent you from bringing these into the venue. I really hope that you will help us in saving Fabric and London's club culture. Kind regards, From: To: Licensing Subject: Fabric license & possible closure Date: 24 August 2016 14:04:31 Hello, I know you have probably been inundated with many an email like the one I am sending you now in regards to Fabric. I however do believe that the club should be kept open as it's such an amazing club and is known all over the world as a pioneer in the drum and bass, house, garage etc, scene and it would be a massive loss in London's nightlife, as alongside Ministry of Sound they are known in all corners of the world for their music and how they contribute to the music industry. -

Former Prodigy Star Assaults Imperial Student at Union

Imperial innovation Bouncy boxing Cheeky monkeys Sword sport The puffer fish and cancer This, and ten other photos Daren King’s new novel The Fencing Club compete research, page 5 from Freshers Week, page 15 Jim Giraffe reviewed, page 21 in Hong Kong, page 24 The student newspaper of Imperial College ● Established 1949 ● Issue 1301 ● Thursday 14 October 2004 ● www.felixonline.co.uk Change of heart The President of Imperial College Union offered his res- Former Prodigy star assaults ignation on Tuesday morning but then withdrew it a day later. uNEWS page 2 Imperial student at Union Own Man Utd Forget supporting the big- By Dave Edwards gest football club in the world Editor – own them! It’s not quite as ridiculous as it sounds... An Imperial College student uBUSINESS page 4 was assaulted in dBs last Wednesday by Keith Flint, the Mobile mysteries former Prodigy vocalist, and “Mobile networks in the UK two other men. are known to be dodgy when Mr Flint, 35, and his new it comes to educating poten- band Clever Brains Fryin’, tial customers about the true played live at the Union cost of using their services.” as part of Freshers Week. uCOMMENT page 7 During their performance, the student, who does not Rat race wish to be named, was appar- “We decided to hide with ently dancing the ‘macarena’ our water guns and launch a in front of the stage. This may surprise attack from behind, have offended the band mem- showering all the racers and a bers. According to witnesses, fair few passers by as well.” Mr Flint and two of his col- u CLUBS AND SOCIETIES leagues then jumped down off page 8 the stage and began to punch Shooting success? “The student A report on a mixed year for the Imperial College Union was left with Rifle and Pistol Club. -

Every Year DJ Mag Hosts the Best of British Awards — Shining a Light on UK Talent on Our Own Doorsteps

BEST OF BRITISH Every year DJ Mag hosts the Best Of British Awards — shining a light on UK talent on our own doorsteps. A counterpoint to the global Top 100 DJs poll, which has grown into an international phenomenon, the way the awards work is that the staff at DJ Mag HQ nominate five names for each category — Best DJ, Best Label etc. This is then put to a public vote, and the winners interviewed and profiled over the following 18 editorial pages. By now our star-studded Best Of British awards party at Egg LDN will have happened, with all the winners and nominees celebrating everything that’s great about the UK scene. Read on for who has received the accolades for this latest edition… djmag.com 027 BEST OF BRITISH 2016 BEST DJ OTHER NOMINEES DANIEL AVERY DJ HARVEY DJ EZ MAYA JANE COLES 24-HOUR PARTY-STARTER SASHA The UK garage pioneer who raised £60,000 for Cancer Research with his around-the-clock live stream had his biggest year yet in 2016... rom his past on pirate radio to the arenas he’s Ever since his days on Kiss FM and mixing the ‘Pure He’s also hinted that he’s going to test his musical filling today, DJ EZ has gone from the face of UK Garage’ compilations, he’s served as the undisputed limits too. “I’m really into the music right now,” he garage to a world-famous brand almost in the flag-bearer of his chosen sound. However, subsequent explained when he appeared on the cover of DJ Mag F space of a year. -

Points Asked How Many Times Today

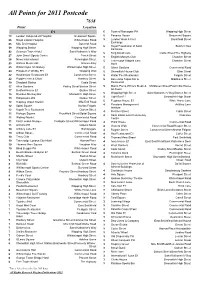

All Points for 2011 Postcode 7638 Point Location E1 6 Town of Ramsgate PH Wapping High Street 73 London Independent Hospital Beaumont Square 5 Panama House Beaumont Square 66 Royal London Hospital Whitechapel Road 5 London Wool & Fruit Brushfield Street Exchange 65 Mile End Hospital Bancroft Road 5 Royal Foundation of Saint Butcher Row 59 Wapping Station Wapping High Street Katharine 42 Guoman Tower Hotel Saint Katharine’s Way 5 King David Lane Cable Street/The Highway John Orwell Sports Centre Tench Street 27 5 English Martyrs Club Chamber Street News International Pennington Street 26 5 Travelodge Aldgate East Chamber Street 25 Wiltons Music Hall Graces Alley Hotel 25 Whitechapel Art Gallery Whitechapel High Street 5 Albert Gardens Commercial Road 24 Prospect of Whitby PH Wapping Wall 5 Shoreditch House Club Ebor Street 22 Hawksmoor Restaurant E1 Commercial Street 5 Water Poet Restaurant Folgate Street 22 Poppies Fish & Chips Hanbury Street 5 Barcelona Tapas Bar & Middlesex Street 19 Shadwell Station Cable Street Restaurant 17 Allen Gardens Pedley Street/Buxton Street 5 Marco Pierre White's Steak & Middlesex Street/East India House 17 Bedford House E1 Quaker Street Alehouse Wapping High Street Saint Katharine’s Way/Garnet Street 15 Drunken Monkey Bar Shoreditch High Street 5 Light Bar E1 Shoreditch High Street 13 Hollywood Lofts Quaker Street 5 Pegasus House E1 White Horse Lane 12 Stepney Green Station Mile End Road 5 Pensions Management Artillery Lane 12 Spital Square Norton Folgate 4 Institute 12 Kapok Tree Restaurant Osborn Street -

Endangered Nightlife

Endangered Nightlife by Silvia Bombardini Charles Jeffrey LOVERBOY, SS17 – via i-D Over the last decade, nearly half of British nightclubs have called it quits: The Night Time Industries Association reports that there were 3144 of them in 2005, and only 1733 still stood in 2015. On September 6 this year, London’s illustrious Fabric forever shut its doors, in the wake of Passing Clouds, and Studio 338 that in August went up in flames. Madame Jojo’s and The Black Cap, storied burlesque venues with over half a century of parties each under their roofs, had danced before them to their swan songs – along with Power Lunches, Crucifix Lane, Dance Tunnel and Plastic People, Cable, The Fridge, Turnmills, and The End. London’s nightlife, it seems, is a species in dire need of protection, and major cities across the UK appear to suffer of a similar plague: when Glasgow’s The Arches lost its licence last year, countless mourned its loss. Yet just across the Channel, clublands prosper. Not a week had passed since Fabric’s closure that its German cousin, Berlin’s Berghain, was to be officially recognised as a cultural or high art institution, and will thus be allowed to pay less taxes. There’s more to it than Kapital, too: lifted in the eyes of the authorities to the same category of concert halls, Berghain’s legal case validates that techno is as quintessential as classical music to Berlin’s cultural scene. But if Berlin’s nighttime crown shan’t be questioned yet, it’s the newfound international relevance of venues like Nordstern in Basel, or festivals such as KaZantip in the Crimean town of Popivka that marks a shift of perspective. -

Booklet Is a Series of Objects That Form Part of the Museum of London’S Vast and Truly Welcome to the Night Museum Fantastic Collection

Welcome to The Night Museum Jes Fernie and Lauren Parker 2 Lost Joanna Walsh 4 Objects from the Museum of London Darkness Matthew Beaumont 12 Objects from the Museum of London A Natural History of the Theatre Frances Morgan 24 Objects from the Museum of London The Night Museum Programme The Museum of Lost Sounds 34 The Museum of Dark Places 37 The Museum of Last Parties 43 To the morally benighted and mentally unhinged: Interspersed throughout the booklet is a series of objects that form part of the Museum of London’s vast and truly Welcome to The Night Museum fantastic collection. They are presented here in a playful way, making oblique and curious connections to the night, across time, subject matter and media. The Museum of London invites you to celebrate the dark, Nicky Deeley’s mythical creatures gleefully stalk these the illicit, and the lost. Here you can immerse yourself in pages, echoing her performance in The Museum of Dark an eclectic and magical series of events involving mythical Places in which two species engage in a nocturnal rite of creatures, sonic installations, whispering objects, ghost exchange and ingestion in the parks and gardens around clubs, drinking dens, experimental performances, thought the Museum of London. experiments and tours of the night. The guidebook concludes with an homage to London’s Musicians, artists and writers will inhabit secret and ghost clubs and lost night haunts, resurrected for one night evocative spaces in and around the museum, including the only in The Museum of Last Parties. Barber Surgeons’ Garden, Postman’s Park, and Roman City We wish you strange and unexpected encounters and, Wall.