The Language Attitudes of Minangkabau People Towards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Use and Attitudes Among the Jambi Malays of Sumatra

Language Use and Attitudes Among the Jambi Malays of Sumatra Kristen Leigh Anderbeck SIL International® 2010 SIL e-Books 21 ©2010 SIL International® ISBN: 978-155671-260-9 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair Use Policy Books published in the SIL Electronic Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or educational purposes free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Editor-in-Chief George Huttar Volume Editors Grace Tan Rhonda Hartel Jones Compositor Margaret González Acknowledgements A number of people have contributed towards the completion of this study. First of all, I wish to express sincere appreciation for the assistance of Prof. Dr. James T. Collins, my academic supervisor. His guidance, valuable comments, and vast store of reference knowledge were helpful beyond measure. Many thanks also go to several individuals in ATMA (Institute of Malay World and Civilization), particularly Prof. Dato’ Dr. Shamsul Amri Baruddin, Prof. Dr. Nor Hashimah Jalaluddin, and the office staff for their general resourcefulness and support. Additionally, I would like to extend my gratitude to LIPI (Indonesian Institute of Sciences) and Pusat Pembinaan dan Pengembangan Bahasa (Indonesian Center for Language Development) for sponsoring my fieldwork in Sumatra. To Diana Rozelin, for her eager assistance in obtaining library information and developing the research instruments; and to the other research assistants, Sri Wachyunni, Titin, Sari, Eka, and Erni, who helped in gathering the data, I give my heartfelt appreciation. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

Minangkabau Traditionally Specific Language Intext of Pasambahan Manjapuik Marapulaiused in Solok City: a Study on Politeness Strategy

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 24, Issue 8, Ser. 3 (August. 2019) 14-24 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Minangkabau Traditionally Specific Language inText of Pasambahan Manjapuik MarapulaiUsed in Solok City: a Study on Politeness Strategy Zulfian ElfiandoProf. Dr. N.L Sutjiati Beratha, M. A. Prof. Dr. I Ketut Darma Laksana, M. Hum.Prof. Dr. Oktavianus, M. Hum. Corresponding Author: Zulfian Elfiando Abstract: This article aims to study Textof Pasambahan Manjapuik Marapulai (TPMM),a speech of traditional language of Minangkabau used in bringing-home proposal of bridegroom to bride’s house. It is a culturally important and traditionally specific language on which implementation of Minangkabau traditions (ceremonies) are greatly based. The traditions cannot be implemented traditionally regardless of the language. Doe to the language role, this article discusses two things, namely the strategy of positive politeness and the strategy of negative politeness in the text pasambahan manjapuik marapulai in Kota Solok as an effort to preserve and develop it to young generations. Additionally the study on the specific language is fewly held by scholars.This article applies qualitative descriptive research. Data areobtained from surveyin Solok city that took place during the pasambahan ceremony, and analyzed qualitatively using socio-pragmatic theorycarried out in four stages, namely data collection, data reduction, data presentation followed by conclusions of research results. The result is that PMM contains negative participant's politeness strategy includingthe use of indirect expressions andthe use of expressions which are full of caution and pessimistic tendency, the use of the respecting words, and apology. -

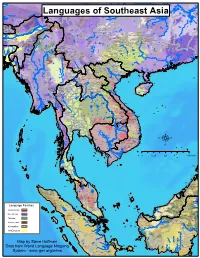

Languages of Southeast Asia

Jiarong Horpa Zhaba Amdo Tibetan Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Wu Chinese Central Tibetan Khams Tibetan Muya Huizhou Chinese Eastern Xiangxi Miao Yidu LuobaLanguages of Southeast Asia Northern Tujia Bogaer Luoba Ersu Yidu Luoba Tibetan Mandarin Chinese Digaro-Mishmi Northern Pumi Yidu LuobaDarang Deng Namuyi Bogaer Luoba Geman Deng Shixing Hmong Njua Eastern Xiangxi Miao Tibetan Idu-Mishmi Idu-Mishmi Nuosu Tibetan Tshangla Hmong Njua Miju-Mishmi Drung Tawan Monba Wunai Bunu Adi Khamti Southern Pumi Large Flowery Miao Dzongkha Kurtokha Dzalakha Phake Wunai Bunu Ta w an g M o np a Gelao Wunai Bunu Gan Chinese Bumthangkha Lama Nung Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Norra Wusa Nasu Xiang Chinese Chug Nung Wunai Bunu Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Min Bei Chinese Nupbikha Lish Kachari Ta se N a ga Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nung Large Flowery Miao Nyenkha Chalikha Sartang Lisu Nung Lisu Southern Pumi Kalaktang Monpa Apatani Khamti Ta se N a ga Wusa Nasu Adap Tshangla Nocte Naga Ayi Nung Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Nocte Naga Lisu Large Flowery Miao Northern Dong Khamti Lipo Wusa NasuWhite Miao Nepali Nepali Lhao Vo Deori Luopohe Miao Ge Southern Pumi White Miao Nepali Konyak Naga Nusu Gelao GelaoNorthern Guiyang MiaoLuopohe Miao Bodo Kachari White Miao Khamti Lipo Lipo Northern Qiandong Miao White Miao Gelao Hmong Njua Eastern Qiandong Miao Phom Naga Khamti Zauzou Lipo Large Flowery Miao Ge Northern Rengma Naga Chang Naga Wusa Nasu Wunai Bunu Assamese Southern Guiyang Miao Southern Rengma Naga Khamti Ta i N u a Wusa Nasu Northern Huishui -

Sijobang: Sung Narrative Poetry of West Sumatra

SIJOBANG: SUNG NARRATIVE POETRY OF WEST SUMATRA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London by Nigel Godfrey Phillips ProQuest Number: 10731666 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731666 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 ABSTRACT In the sphere of Malay and Indonesian literature, it is only re cently that students of oral narratives have paid attention to their character as oral performances, and this thesis is the first study of a West Sumatran metrical narrative to take that aspect of it into account. Versions of the story of Anggun Nan Tungga exist in manuscript and printed form, and are performed as dramas and sung narratives in two parts of West Sumatra: the coastal region of Tiku and Pariaman and the inland area around Payakumbuh. Stgobang is the sung narrative form heard in the Payakumbuh area. It is performed on festive occasions by paid story-tellers called tukang s'igobang,, who le a r n th e s to r y m ainly from oral sources. -

Inventory of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Library of the University of Leiden

INVENTORIES OF COLLECTIONS OF ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS INVENTORY OF THE ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LEIDEN VOLUME 7 MANUSCRIPTS OR. 6001 – OR. 7000 REGISTERED IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY IN THE PERIOD BETWEEN MAY 1917 AND 1946 COMPILED BY JAN JUST WITKAM PROFESSOR OF PALEOGRAPHY AND CODICOLOGY OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY INTERPRES LEGATI WARNERIANI TER LUGT PRESS LEIDEN 2007 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007. The form and contents of the present inventory are protected by Dutch and international copyright law and database legislation. All use other than within the framework of the law is forbidden and liable to prosecution. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First electronic publication: 17 September 2006. Latest update: 30 July 2007 Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007 2 PREFACE The arrangement of the present volume of the Inventories of Oriental manuscripts in Leiden University Library does not differ in any specific way from the volumes which have been published earlier (vols. 5, 6, 12, 13, 14, 20, 22 and 25). For the sake of brevity I refer to my prefaces in those volumes. A few essentials my be repeated here. Not all manuscripts mentioned in the present volume were viewed by autopsy. The sheer number of manuscripts makes this impossible. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Guanyinqiao Horpa Zhaba Amdo Guiqiong Queyu Horpa Chinese, Wu Muya Tibetan Khams Chinese, Huizhou Moinba Hmong, Eastern Xiangxi Luoba, Yidu Tujia, Northern Luoba, Bogaer LanguagesErsu of Southeast Asia Luoba, Yidu Tibetan Chinese, Mandarin Digaro Pumi, Northern Luoba, YiduDarang Deng Namuyi Luoba, Bogaer Geman Deng Hmong, Eastern Xiangxi Atuence Shixing Hmong Njua Tibetan Idu Idu Yi, Sichuan Tibetan Tshangla Miju Drung Hmong Njua Moinba Bunu, Wunai Hmong, Northeastern Dian Dzongkha Adi Phake Khamti Pumi, Southern Bunu, Wunai Kurtokha Dzalakha Choni Gelao Chinese, Gan Bumthangkha Moinba Lama Nung Yi, Guizhou Yi, Guizhou Bunu, Wunai Chinese, Xiang Norra Bunu, Wunai Chocangacakha Dakpakha Khamti Chinese, Min Bei Nupbikha Kachari Naxi Hmong Njua Brokpake Nisi Khamti Nyenkha Chalikha Naga, Tase LisuNung Lisu Hmong, Northeastern Dian Pumi, Southern Apatani Khamti Naga, Tase Yi, Guizhou Adap Tshangla Naga, Nocte Ayi Khengkha Rawang Gongduk Tshangla Sherdukpen Naga, Nocte Lisu Hmong, Northeastern Dian Dong, Northern Khamti Lipo Yi, GuizhouHmong Daw Nepali Nepali Maru Deori Hmong, LuopoheHmong, Chonganjiang Pumi, Southern Nepali Naga, Konyak Nusu Hmong Daw Gelao GelaoHmong, Northern GuiyangHmong, Luopohe Bodo Kachari Lipo Hmong Daw Khamti Lipo Gelao Hmong, Northern QiandongHmong, Eastern Qiandong Assamese Hmong, Northeastern Dian Hmong Daw Hmong Njua Naga, Phom Khamti Zauzou Lipo Hmong, Chonganjiang Naga, Ntenyi Yi, Guizhou Bunu, Wunai Hmong, Southern Guiyang Naga, Rengma Khamti Tai Nua Yi, Guizhou Hmong, Northern Huishui Bunu, Bu-Nao Naga, Ao -

The Impact of the West Sumatran Regional Recording Industry on Minangkabau Oral Literature

Wacana, Vol. 12 No. 1 (April 2010): 35—69 The impact of the West Sumatran regional recording industry on Minangkabau oral literature SURYADI Abstract Due to the emergence of what in Indonesian is called industri rekaman daerah ‘Indonesian regional recording industries’, which has developed significantly since the 1980s, many regional recording companies have been established in Indonesia. As a consequence, more and more aspects of Indonesian regional culture have appeared in commercial recordings. Nowadays commercial cassettes and Video Compact Discs (VCDs) of regional pop and oral literature genres from different ethnic groups are being produced and distributed in provincial and regency towns, even those situated far from the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. Considering the extensive mediation and commodification of ethnic cultures in Indonesia, this paper investigates the impact of the rise of a regional recording industry on Minangkabau oral literature in West Sumatra. Focussing on recordings of some Minangkabau traditional verbal art genres on commercial cassettes and VCDs by West Sumatran recording companies, this paper attempts to examine the way in which Minangkabau traditional verbal art performers have engaged with electronic communication, and how this shapes technological and commercial conditions for ethnic art and performance in one modernizing society in regional Indonesia. Keywords Oral literature, oral tradition, traditional verbal art, media technology, Minangkabau, West Sumatra, regional recording industries, cultural mediation, representation of traditional culture, commodification of cultural practices, cassette, VCD. SURYADI is a lecturer in Indonesian studies at Leiden Institute for Area Studies / School of Asian Studies, Leiden University, and a PhD candidate at Leiden University. His research interests are oral tradition, literary life, and media culture in Indonesia. -

Lexical Variations of Minangkabau Language Within West Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia: a Dialectological Study

GEOGRAFIA OnlineTM Malaysia Journal of Society and Space 13 issue 3 (1-10) © 2017, ISSN 2180-2491 1 Lexical variations of Minangkabau Language within West Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia: A dialectological study Reniwati1, Midawati2, Noviatri1 1Jabatan Sastera, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Andalas Padang, 2Jabatan Sejarah, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Universitas Andalas Padang Correspondence: Reniwati (email: [email protected]) Abstract Minangkabau people have a long history of migrating overseas especially to Peninsular Malaysia. They migrated to overseas with their soul, original culture and language. This study attempted to trace the Minangkabau of the language’s aspects, in particular, lexical aspect by using the theory in dialectology. For grouping variations of language is used the dialektometri’s method. Within the framework of solving the problem of research, there are three stages of the method used: 1) the stage providing data; 2) the stage analysing data; and 3) the stage presenting the analysis results. The population of this study was the whole speech Minangkabau society in the area of origin (Kabupten 50 Kota and Kabupaten Tanah Datar) and in the overseas area (Negeri Sembilan, Melaka and Pahang). The sample was speech Minangkabau society in Nagari Koto Baru Simalanggang and Nagari Rao-Rao. The sample in the overseas area is a region of Rembau, Naning and Kuantan. After being done the comparison, the fourth samples show the lexical similarities and lexical differences. However, the calculation of dialecttometric method is not indicating the degree of variation at the languages and dialects level. It is only at the subdialect and different talk level. The lexical differences in overseas areas show that there has been a change. -

Social Science Research and Conservation Management in the Interior of Borneo Unravelling Past and Present Interactions of People and Forests

SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH AND CONSER The Culture & Conservation Research Program in Kayan Mentarang National Park, East Kalimantan, constituted a unique interdisciplinary engagement in central Borneo that lasted for six years (1991-97). Based on original ethnographic, ecological, and historical data, this volume comprehensively describes the people and the environment of this region and makes MANAGEMENT VATION IN THE INTERIOR OF BORNEO a rare contribution to the understanding of past and present interactions between people and forests in central Borneo. Kayan Mentarang has thus become one of the ethnographically best known protected areas in Southeast Asia. By pointing at the interface between research and forest management, this book offers tools for easing the antagonism between applied and scholarly research, and building much needed connections across fields of knowledge. ISBN 979-3361-02-6 Unravelling past and present interactions of people and forests Edited by Cristina Eghenter, Bernard Sellato Cristina Eghenter, and G. Simon Devung Editors Cristina Eghenter Bernard Sellato G. Simon Devung COVER Selato final 1 6/12/03, 1:20 AM Social Science Research and Conservation Management in the Interior of Borneo Unravelling past and present interactions of people and forests Editors Cristina Eghenter Bernard Sellato G. Simon Devung 00 TOC selato May28.p65 1 6/11/03, 11:53 AM © 2003 by CIFOR, WWF Indonesia, UNESCO and Ford Foundation All rights reserved. Published in 2003 Printed by Indonesia Printer, Indonesia WWF Indonesia holds the copyright to the research upon which this book is based. The book has been published with financial support from UNESCO through its MAB Programme. The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the organisation. -

Variation Phonology of Indonesian Language in Minangkabau Speakers

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 8, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2019 ISSN 2277-8616 Variation Phonology Of Indonesian Language In Minangkabau Speakers Dea Rakhimafa Wulandari, Aninditya Sri Nugraheni Abstract: Indonesian is used as the main means of students who come from Padang to communicate, both in the fields of education, technology, and social activities. However, Indonesian is not the first language of Padang students. As a result, variations in certain vocabulary words appear in the Indonesian language. The purpose of this study is to describe variations of Indonesian phonology in Minangkabau language students. Things discussed were about vowels, consonants, and phenomena at the phonological level of Minangkabau language students in speaking Indonesian. The method used in this research is descriptive qualitative method with observation and recording techniques. The data that has been obtained in the analysis using descriptive analytic methods. The results of this study found that there are differences in vowels and consonants in the two languages, in Indonesian there are 6 vowels and 21 consonants and Minangkabau language 5 vowels and 19 consonants, launching vowels ê to a vowel phoneme both after phoneme i and phoneme u, vocal changes / a / becomes the vowel phoneme / o /, changes consonants to [s] and [k] to [h], sound absorption and sound addition. Keywords: Phonological Variations, Indonesian Language, Minangkabau Language Speakers —————————— —————————— 1. INTRODUCTION Minangkabau language students speak some vocabulary in The country of Indonesia is a country that has a diversity of Indonesian. This can be seen when both the Minangkabau languages [1]. Almost all of them are scattered throughout this people and the Minangkabau language users speak vowels in region of Indonesia. -

Challenges of Learning Spoken English in Minangkabau Context

ISELT-5 Proceedings of the Fifth International Seminar on English Language and Teaching (ISELT-5) 2017 CHALLENGES OF LEARNING SPOKEN ENGLISH IN MINANGKABAU CONTEXT Meylina STMIK Jayanusa Padang email: [email protected] Abstract Considering the background languages, there are internal and external challenges for Minangkabau-Indonesian EFL students in their speaking ability. Even within one indigenous language, they basically speak in different dialects and accents. They need to accomodate these challenges into a proper english usage. This paper is aimed at investigating the speaking problems of the students and the factors affecting their speaking performance. The writer uses a questioner addressed to 60 students from STMIK Jayanusa Padang and IAIN Imam Bonjol Padang. The findings of this paper indicates that psychological factors are the major problems in learning spoken English. Among these are lack of self-confidence, lack of aptitude, lack of motivation, anxiety, and shyness. The study was expected to help students improve their performance in speaking and have more exposure to the language. Key words : Speaking problems, Minangkabau-Indonesian EFL context, psychological factors. 1. INTRODUCTION Language is a media that is used to express humans’ opinions and feelings. Language can not be separated from human because it always exist in their activities. Through language, human can grant their culture to the next generation. The people of West Sumatera, as well as general language society in Indonesia, is bilingual society. Bilingualism is a characteristics of most societies in the world; most children in the world today is also bilingual. Minangkabau children who live in Padang are mainly bilingual; they can speak in their mother tongue, the Minangkabau language, and the national language, Bahasa Indonesia.