Colonized by the Dark Whites Freed by Grace: an Analysis of the First Two Mizo Written Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM (A UGC Notified Journal) Vol. XVIII Revisiting Mizo Heroes Mizo History Association September 2017 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor Rohmingmawii The views and interpretations expressed in the Journal are those of the individual author(s)’ and do not necessearily represent the views of the Editor or Mizo History Association. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XVII (A UGC Recognised Journal) September 2017 Editor Rohmingmawii Assistant Professor Department of History Pachhunga University College, Aizawl MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2015 – 2017) President : Prof. Sangkima, Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna, Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte, Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana, Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati, Govt. Hrangbana College Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga, Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo, Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana, Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga, Govt. Aizawl West College Mr. Robert Laltinchhawna, Govt. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

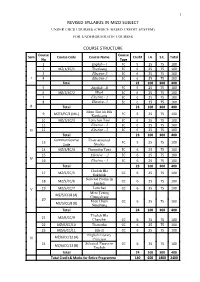

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

TDC Syllabus Under CBCS for Persian, Urdu, Bodo, Mizo, Nepali and Hmar

Proposed Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (Honours) Persian 1 B.A. (Hons.): Persian is not merely a language but the life line of inter-disciplinary studies in the present global scenario as it is a fast growing subject being studied and offered as a major subject in the higher ranking educational institutions at world level. In view of it the proposed course is developed with the aims to equip the students with the linguistic, language and literary skills for meeting the growing demand of this discipline and promoting skill based education. The proposed course will facilitate self-discovery in the students and ensure their enthusiastic and effective participation in responding to the needs and challenges of society. The course is prepared with the objectives to enable students in developing skills and competencies needed for meeting the challenges being faced by our present society and requisite essential demand of harmony amongst human society as well and for his/her self-growth effectively. Therefore, this syllabus which can be opted by other Persian Departments of all Universities where teaching of Persian is being imparted is compatible and prepared keeping in mind the changing nature of the society, demand of the language skills to be carried with in the form of competencies by the students to understand and respond to the same efficiently and effectively. Teaching Method: The proposed course is aimed to inculcate and equip the students with three major components of Persian Language and Literature and Persianate culture which include the Indo-Persianate culture, the vital portion of our secular heritage. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

September, 2019

September 2019 Ramthar 1 www.mizoramsynod.org September 2019 Ramthar 2 www.mizoramsynod.org September 2019 Ramthar 3 I BEI RUAL ANG U Editorial Nikum 2018 khán Beihrual Centenary hlim takin kan hmang a. Kumin hi Beihrual kum 101-na lai a lo tling leh ta. Beihrual hmangtu zawng zawngte Ramthar Editorial Board member-ten Pathian hmingin chibai kan bûk che u a, duhsakna kan hlàn nghâl bawk a che u. Ringtu hmasate kha ‘Pathian thuâwih’ tiin sawi an ni \hìn a. Hei hian Pathian mi an nih bâkah a thu zàwmtute an nih a hril nghâl bawk. Ringtu hmasate kha chuan sual leh thil \ha lo an hriat apiang kalsanin Isua an ring bur mai a ni. Chu chuan an nun a tihlim êm êm a; sual hmachhawn tùr pawh ni se, an hlau lo va, an zâm ve mai ngai lo. Chanchin |ha neitu chu hril duhna leh châknain a khat \hìn. Lal Isuan, “Khaw dangah te pawh Pathian Ram Chanchin |ha ka hril tùr a ni; chumi avàng chuan tirh ka ni si a,” (Lk 4:43) a tih angin, an chhúngte leh an khaw \henawmte an vei a. An hmuh leh hriat chu chang ve se an ti; ‘Fangrual Pawl’ te awmin a huhovin khaw hlá leh hnaiah Chanchin |ha chu an feh chhuahpui \hìn. Mizoten Chanchin |ha kan hrilna ram mite hi anmahni hnam invei zui apiangten an vànneihpui tlángpui. Chanchin |ha hrilh buaipui lo - mi mal, chhúngkua, kohhran, ram leh hnam chuan a aia \angkai lo leh \ha lo zâwk thil dang an buaipui tho tho va, an nunin a chhiatphah \hìn. -

New Additions to Parliament Library

NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English 000 GENERALITIES 1 Crouch, James S. A bibliography of Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy / James S. Crouch.-- New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2002. 430p.; 25cm. ISBN : 81-7304-428-7. 016.828 CRO-c C73781 Price : RS.**1000.00 2 Mathew, Mammen, ed. Manorama Yearbook 2015 / edited by Mammen Mathew.-- Kottayam: Malayala Manorama, 2015. 1038p.; 20cm. R 030 MAT-m B209257(Ref.) Price : RS.***250.00 3 McWhirter, Norris Guinness book of world records / Norris McWhirter and Ross McWhirter.-- New York: Bantam Press, 1974. 672p.: plates; 19cm. R 032.02 GUI B80309(Ref.) Price : RS.***895.00 4 General.-- [s.l.]: [s.n.], [2015]. v.p.; 33cm. Multilingual. R 070.403 GEN OB4138(2) (Ref.) 5 Rodrigues, Usha M. India news media: from observer to participant / Usha M. Rodrigues and Maya Ranganathan.-- New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2015. xiv, 240p.: plates; 22cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN : 978-93-515-0050-6. 079.54 USH-in B209246 Price : RS.***895.00 6 Aiyar, V.R. Krishna Letters and lectures of an anguished soul / V.R. Krishna Iyer.-- Madurai: Society for Community Organisation Trust , 2013. vi, 155p.; 21cm. 080 AIY-l C73627 7 Chawla, Bindu Conversations with Pandit Amarnath / Bindu Chawla.-- New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2004. xiii, 173p.: plates; 25cm. ISBN : 81-85503-07-9. 080 AMA-b C73799 Price : RS.***435.00 8 Champions: the world's greatest cricketers speak: conversations with Mike Coward.-- New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014. x, 243p.: plates; 24cm. First published by Allen and Unwin Australia, 2013. -

C:\Documents and Settings\All U

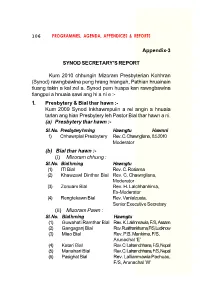

106 PROGRAMMES, AGENDA, APPENDICES & REPORTS Appendix-3 SYNOD SECRETARY’S REPORT Kum 2010 chhungin Mizoram Presbyterian Kohhran (Synod) rawngbawlna peng hrang hrangah, Pathian hruainain tluang takin a kal zel a. Synod pum huapa kan rawngbawlna tlangpui a hnuaia sawi ang hi a ni e :- 1. Presbytery & Bial thar hawn :- Kum 2009 Synod Inkhawmpuiin a rel angin a hnuaia tarlan ang hian Presbytery leh Pastor Bial thar hawn a ni. (a) Presbytery thar hawn :- Sl. No.Presbytery hming Hawngtu Hawnni 1) Chhawrpial Presbytery Rev. C. Chawngliana,8.5.2010 Moderator (b) Bial thar hawn :- (i) Mizoram chhung : Sl. No.Bial hming Hawngtu (1) ITI Bial Rev. C. Rosiama (2) Khawzawl Dinthar BialRev. C. Chawngliana, Moderator (3) Zonuam Bial Rev. H. Lalchhanhima, Ex-Moderator (4) Rengtekawn Bial Rev. Vanlalzuata, Senior Executive Secretary (ii) Mizoram Pawn : Sl. No.Bial hming Hawngtu (1) Guwahati Ramthar BialRev. K. Lalrinmawia, F/S, Assam (2) Gangaganj Bial Rev. Rualthankhuma, F/S, Lucknow (3) Miao Bial Rev. P.B. Mankima, F/S, Arunachal ‘E’ (4) Katari Bial Rev. C. Lalramchhana, F/S, Nepal (5) Manahari Bial Rev. C. Lalramchhana, F/S, Nepal (6) Pasighat Bial Rev. Lallianmawia Pachuau, F/S, Arunachal ‘W’ PROGRAMMES, AGENDA, APPENDICES & REPORTS 107 (7) Chakmaghat Bial Rev. C. Zorammawia, F/S, Tripura (8) Tuingoi Bial Rev. Ralthansanga Ralte, A/ S, Barak Area 2. Pastor leh Pro. Pastor Induction :- Synod Inkhawmpui 2009-in a rel angin Pastor thawklai, Nemngheh thar te leh Pro. Pastor lak tharte an vaiin an awmna turah 17th January, 2010 khan tluang taka dahngheh (induct) vek an ni a. Pastor zirna sang zawka zir, April 2010-a zir zote pawh 9th May 2010-ah an awmna turah dahngheh (induct) vek an ni bawk. -

Generating Knowledge on Lushai Hills: the Works of T.H Lewin

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Generating Knowledge on Lushai Hills: The Works of T.H Lewin H.Vanlalhruaia* Ramdinsangi** Abstract The main objective of this paper is to situate colonialism and European ethnographic practices in the process of Mizo history making in the second half of nineteen century Lushai Hills. Until the appointment of T.H Lewin [Thangliana] (1839-1916) as Deputy Commissioner of Hill Tract, the British had little knowledge on the details of the Mizos and their cultural history. He was appointed to confront the problem of how to come to terms with the Mizo (Lushai and Shendu) chiefs who were constantly “hostile” to the British. Lewin early career in India was describe by himself in his ethnographic text “A fly on the Wheel or How I helped to Govern India” published in 1885. The work of T.H Lewin has been described extensively in Mizo literary circles –mostly his contributions toward the Mizo society in a straightforward manner. He has been often portrayed as a paternalist figure of Mizo society. One of the main objectives of this paper is to inject further discussion and debate on his European background and his love for the Mizo people in the course of colonial territorial- making in North East India. Key Words: Knowledge, Colonial, Ethnography, Tribe, Lushai, European, Paternalist The main objective of this paper is to generated and produced throughout their situate colonialism and European association with the Mizos. Particularly ethnographic practices in the process of from the second half of the nineteenth Mizo history making in the second half century, Lushai Hills becomes – what of nineteenth century Lushai Hills. -

National Affairs

NATIONAL AFFAIRS Prithvi II Missile Successfully Testifi ed India on November 19, 2006 successfully test-fi red the nuclear-capsule airforce version of the surface-to- surface Prithvi II missile from a defence base in Orissa. It is designed for battlefi eld use agaisnt troops or armoured formations. India-China Relations China’s President Hu Jintao arrived in India on November 20, 2006 on a fourday visit that was aimed at consolidating trade and bilateral cooperation as well as ending years of mistrust between the two Asian giants. Hu, the fi rst Chinese head of state to visit India in more than a decade, was received at the airport in New Delhi by India’s Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Science and Technology Minister Kapil Sibal. The Chinese leader held talks with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in Delhi on a range of bilateral issues, including commercial and economic cooperation. The two also reviewed progress in resolving the protracted border dispute between the two countries. After the summit, India and China signed various pacts in areas such as trade, economics, health and education and added “more substance” to their strategic partnership in the context of the evolving global order. India and China signed as many as 13 bilateral agreements in the presence of visiting Chinese President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The fi rst three were signed by External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing. They are: (1) Protocol on the establishment of Consulates-General at Guangzhou and Kolkata. It provides for an Indian Consulate- General in Guangzhou with its consular district covering seven Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hainan, Yunnan, Sichuan and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. -

E-Newsletter

ALL-INDIA WRITERS' MEET 24-25 March 2018, Kohima, Nagaland In collaboration with Nagaland University, a two-day All-India Writers' Meet was organized on 24-25 March 2018 at Kohima, Nagaland. For the first time the Akademi organized a national-level programme at Nagaland. The very objective of this mega event was a challenge to bring reputed writers from various languages and from different parts of the country to Nagaland and usher in a new environment for the Naga writers. This was an opportunity to bring together different languages of the country with the languages of Nagaland. Dr K. Sreenivasarao, Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, while welcoming the delegates, encouraged the native writers to bring out the beautiful Naga cultural and literary traditions so as to make them known to others. Dr D. Kuolie, General Council Member, Sahitya Akademi, asserted that the idea of organizing this event was a constructive endeavour, an attempt to bring the writers of the country together. Professor Temsula Ao, eminent English writer, delivered the keynote address and observed that the Nagas have a rich oral tradition, but modern generation has lost many knowledgeable story-tellers and folk-singers, which she considered as the greatest casualties of progress and development of the society. She encouraged and appreciated the younger generation to create a new tradition where the soul of oral tradition resonates with new vigour. Prof. Temsula Ao delivering the keynote address Dr Madhav Kaushik speaking during the event Professor Ramesh C. Gupta, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Nagaland University, gave a brief historical account on the institutionalization of Sahitya Akademi and highlighted the aspiration of the pioneers.