E:\Pendrive\Last Edited Mizo St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

The State and Identities in NE India

1 Working Paper no.79 EXPLAINING MANIPUR’S BREAKDOWN AND MANIPUR’S PEACE: THE STATE AND IDENTITIES IN NORTH EAST INDIA M. Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE February 2006 Copyright © M.Sajjad Hassan, 2006 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Development Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Programme, Development Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. 1 Crisis States Programme Explaining Manipur’s Breakdown and Mizoram’s Peace: the State and Identities in North East India M.Sajjad Hassan Development Studies Institute, LSE Abstract Material from North East India provides clues to explain both state breakdown as well as its avoidance. They point to the particular historical trajectory of interaction of state-making leaders and other social forces, and the divergent authority structure that took shape, as underpinning this difference. In Manipur, where social forces retained their authority, the state’s autonomy was compromised. This affected its capacity, including that to resolve group conflicts. Here powerful social forces politicized their narrow identities to capture state power, leading to competitive mobilisation and conflicts. -

Aizol (アイザウル) Travel Guide

Aizol Travel Guide - http://www.ixigo.com/travel-guide/aizol page 1 Max: Min: Rain: 22.20000076 22.20000076 406.100006103515 When To 2939453°C 2939453°C 6mm Aizol Jul Sitting amidst beautiful sky high Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, VISIT umbrella. mountain peaks, tranquil ambiance Max: Min: Rain: and breathtaking scenic beauty, 22.20000076 21.60000038 320.399993896484 http://www.ixigo.com/weather-in-aizol-lp-1046874 2939453°C 1469727°C 4mm Aizawl is an ideal place to spend a Aug relaxed yet adventurous vacation. Jan Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, The capital of the state of the Famous For : City Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. umbrella. Mizoram, the city is a paradise for Max: Min: Rain: Max: Min: Rain: 22.29999923 22.20000076 320.600006103515 15.89999961 11.60000038 13.3999996185302 7060547°C 2939453°C 6mm nature lovers and history A nice place to explore the picturesque 8530273°C 1469727°C 73mm enthusiasts. beauty, Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, calls Feb Sep out to nature lovers. The sunlit days, crystal Cold weather. Carry Heavy woollen. Pleasant weather. Carry Light woollen, clear sky and dewy mornings would enthrall umbrella. Tam Lake, Waterfall Vantawng, Max: Min: Rain: you with their beauty forever. Plus, the place 17.29999923 13.30000019 23.3999996185302 Max: 22.5°C Min: Rain: Phawngpui, Saiha, Dampa and 7060547°C 0734863°C 73mm 21.29999923 305.200012207031 can be visited anytime during the year. On 7060547°C 25mm Reiek are some of the places you the local attractions front, you can visit the Mar Oct must pay a visit to when in Aizawl. -

Understanding the Breakdown in North East India: Explorations in State-Society Relations

Working Paper Series ISSN 1470-2320 2007 No.07-83 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan Published: May 2007 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Web site: www.lse.ac.uk/depts/destin 1 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan DESTIN, London School of Economics 1. Introduction Northeastern India – a compact region made up of seven sub-national states1- has historically seen high levels of violence, stemming mostly from ethnic and separatist conflicts. It was among the first of the regions, to demonstrate, on the attainment of Independence, signs of severe political crisis in the form of nationalist movements. This has translated into a string of armed separatist movements and inter-group ethnic conflicts that have become the enduring feature of its politics. Separatist rebellions broke out first in Naga Hills district of erstwhile Assam State, to be followed by similar armed movement in the Lushai Hills district of that State. Soon secessionism overtook Assam proper and in Tripura and Manipur. Of late Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh have joined the list of States that are characterised as unstable and violent. Despite the attempts of both the state and society, many of these violent movements have continued to this day with serious implications for the welfare of citizens (Table 1). Besides separatist violence, inter-group ethnic clashes have been frequent and have taken a heavy toll of life and property.2 Ethnic violence exists alongside inter-ethnic contestations, over resources and opportunities, in which the state finds itself pulled in different directions, with little ability to provide solutions. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

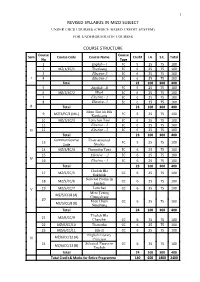

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority

~'iI'lI<l The Mizoram Gazette i EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority Regn No. NE-313 (MZ) 2006-2008 Rs. 2/- per issue VOL - XXXVIII Aizawl, Monday, 1.6.2009, Jyaistha 11, S.E 1931, Issue No.265 NOTIFICATION No.F.23012/2/05-REV, the 25th May, 2009. In pursuance ofthe Aide Memoire ofthe Asian Development Bank's Appraisal Mission under the Mizoram Public Resources Management and development Programme (MPRMDP) the Governor ofMizoram is pleased to approve restructuring ofRevenue Department, Govern ment ofMizoram as per the "Scheme for restructuring ofRevenue Department" at Annexure- 'A'. Lalbiaktluanga Khiangte, Commissioner/Secretary to the Govt. ofMizoram. • Ex-265/2009 -2- GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM REVENUE DEPARTMENT A PLAN FOR RESTRUCTURING AND RATIONALISING REVENUE ADMINISTRATION OF MIZORAM I. Present status of Land Revenue Administration. The primary purpose ofthe administrative struc ture developed by the Government was to deal with land and land revenue administration, including the assessment and collection of revenue, the maintenance of land records, survey for revenue purposes and records ofright, taxes on lands and buildings. An efficient land administration is indispensable for the peace and prosperity ofrural Mizoram and the protection ofthe rights ofownership ofthe people. The basic feature ofthe structure ofthe functionaries are as follows :- There is no administrative machinery at Village level, Circle level, Talug/Tehsil level and Sub Division levels. The district has been the most important unit of land and land revenue administration. The district level functionary forms the base ofthe land and land revenue administration. The head ofthe district administration is designated as Deputy Commissioner assisted by Assistant Settlement Officer I & II. -

Notable Bird Records from Mizoram in North-East India (Forktail 22: 152-155)

152 SHORT NOTES Forktail 22 (2006) Notable bird records from Mizoram in north-east India ANWARUDDIN CHOUDHURY The state of Mizoram (21°58′–24°30′N 92°16′–93°25′E) northern Mizoram, in March 1986 (five days), February is located in the southern part of north-east India (Fig. 1). 1987 (seven days) and April 1988 (5 days) while based in Formerly referred to as the Lushai Hills of southern Assam, southern Assam. During 2–17 April 2000, I visited parts it covers an area of 21,081 km2. Mizoram falls in the Indo- of Aizawl, Kolasib, Lawngtlai, Lunglei, Mamit, Saiha, Burma global biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and Serchhip districts and surveyed Dampa Sanctuary and the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area and Tiger Reserve, Ngengpui Willdlife Sanctuary, (Stattersfield et al. 1998). The entire state is hilly and Phawngpui National Park and the fringe of Khawnglung mountainous. The highest ranges are towards east with Wildlife Sanctuary. This included 61 km of foot transect the peaks of Phawngpui (2,157 m; the highest point in along paths and streams, 2.5 km of boat transects along Mizoram) and Lengteng (2,141 m). The lowest elevation, the Ngengpui River and Palak Dil, and 1,847 km of road <100 m, is in the riverbeds near the borders with Assam transects. During 15–22 February 2001, I visited parts of and Bangladesh border. The climate is tropical monsoon- type with a hot wet summer and a cool dry winter. Table 1. Details of sites mentioned in the text. Temperatures range from 7° to 34°C; annual rainfall ranges from 2,000 to 4,000 mm. -

TDC Syllabus Under CBCS for Persian, Urdu, Bodo, Mizo, Nepali and Hmar

Proposed Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (Honours) Persian 1 B.A. (Hons.): Persian is not merely a language but the life line of inter-disciplinary studies in the present global scenario as it is a fast growing subject being studied and offered as a major subject in the higher ranking educational institutions at world level. In view of it the proposed course is developed with the aims to equip the students with the linguistic, language and literary skills for meeting the growing demand of this discipline and promoting skill based education. The proposed course will facilitate self-discovery in the students and ensure their enthusiastic and effective participation in responding to the needs and challenges of society. The course is prepared with the objectives to enable students in developing skills and competencies needed for meeting the challenges being faced by our present society and requisite essential demand of harmony amongst human society as well and for his/her self-growth effectively. Therefore, this syllabus which can be opted by other Persian Departments of all Universities where teaching of Persian is being imparted is compatible and prepared keeping in mind the changing nature of the society, demand of the language skills to be carried with in the form of competencies by the students to understand and respond to the same efficiently and effectively. Teaching Method: The proposed course is aimed to inculcate and equip the students with three major components of Persian Language and Literature and Persianate culture which include the Indo-Persianate culture, the vital portion of our secular heritage.