Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

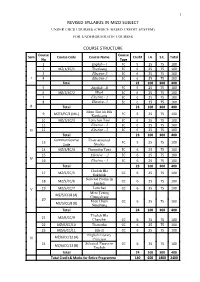

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:5 May 2015 ================================================================= The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. ================================================================= Abstract This paper discusses the problems of English Language Teaching and Learning in Mizoram, a state in India’s North-Eastern region. Since the State is evolving to be a monolingual state, more and more people tend to use only the local language, although skill in English language use is very highly valued by the people. Problems faced by both the teachers and the students are listed. Deficiencies in the syllabus as well as the textbooks are also pointed out. Some methods to improve the skills of both the teachers and students are suggested. Key words: English language teaching and learning, Mizoram schools, problems faced by students and teachers. 1. Introduction In order to understand the conditions and problems of teaching-learning English in Mizoram, it is important to delve into the background of Mizoram - its geographical location, the origin of the people (Mizo), the languages of the people, and the various cultures and customs practised by the people. How and when English Language Teaching (ELT) was started in Mizoram or how English is perceived, studied, seen and appreciated in Mizoram is an interesting question. Its remoteness and location also create problems for the learners. 2. Geographical Location Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:5 May 2015 Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram 173 Figure 1 : Map of Mizoram Mizoram is a mountainous region which became the 23rd State of the Indian Union in February, 1987. -

Beyond Labor History's Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast

Chapter 9 Beyond Labor History’s Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast India, from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century Willem van Schendel 1 Introduction What is global labor history about? The turn toward a world-historical under- standing of labor relations has upset the traditional toolbox of labor histori- ans. Conventional concepts turn out to be insufficient to grasp the dizzying array and transmutations of labor relations beyond the North Atlantic region and the industrial world. Attempts to force these historical complexities into a conceptual straitjacket based on methodological nationalism and Eurocentric schemas typically fail.1 A truly “global” labor history needs to feel its way toward new perspectives and concepts. In his Workers of the World (2008), Marcel van der Linden pro- vides us with an excellent account of the theoretical and methodological chal- lenges ahead. He makes it very clear that labor historians need to leave their comfort zone. The task at hand is not to retreat into a further tightening of the theoretical rigging: “we should resist the temptation of an ‘empirically empty Grand Theory’ (to borrow C. Wright Mills’s expression); instead, we need to de- rive more accurate typologies from careful empirical study of labor relations.”2 This requires us to place “all historical processes in a larger context, no matter how geographically ‘small’ these processes are.”3 This chapter seeks to contribute to a more globalized labor history by con- sidering such “small” labor processes in a mountainous region of Asia. My aim is to show how these processes challenge us to explore beyond the comfort zone of “labor history,” and perhaps even beyond that of “global labor history” * International Institute of Social History and University of Amsterdam. -

![Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0718/hripui-leh-literature-pandemic-and-literature-a-multidisciplinary-approach-may-27-29-2021-1550718.webp)

Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021

THREE DAY NATIONAL WEBINAR ON HRIPUI LEH LITERATURE [PANDEMIC AND LITERATURE : A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH] MAY 27-29, 2021 ORGANISeD BY DePArtMent of Mizo PACHHungA university College [A Constituent College of MizorAM university] ORGANIZING BODY PATRON Prof. H.Lalthanzara Principal, Pachhunga University College CO-PATRON CONveNeR CO-COORDINATORS enid H.Lalrammuani H.Laldinmawia Remlalthlamuanpuia Head & Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Dr. Zoramdinthara COORDINATOR Lalrotluanga Associate Professor Lalrammuana Sailo Assistant Professor Assistant Professor D r . L a l n u n p u i a Renthlei Assistant Professor Webinar Join Zoom Webinar@ 7:30 PM IST on May 27-29, 2021 For Registration WhatsApp Link Pachhunga Mizo Department Mizo Department : [email protected] Scan QR University College Instragram Pachhunga University [email protected] code for Channel mizo_department_puc College (Official) Whatsapp NI KHATNA (DAY ONe) MAY 27 (NINGANI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. vanlalnghaka Ralte B.Sc (Hons)., M.Sc, B.D., M.Th., D.Th. (Professor) Principal, Aizawl Theological College, Mizoram Keynote Speaker Prof. Malsawmliana Dr. Zothanchhingi Khiangte Department of History Assistant Professor, Department of English, Govt. T.Romana College, Aizawl, Mizoram Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Bodoland, India Topic : Hripui leh Mizo Literature – History Thlirna Atangin Topic :Literature Hring Chhuaktu Hripui (Pandemic and Mizo Literature – A Historical Approach) (Pandemic as a Source of Literature) NI HNIHNA (DAY TWO) MAY 28 (ZIRTAWP ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. H. vànlalruata Prof. vanlalnghaka Head, Christian Ministry & Communication Head, Department of Philosophy Aizawl Theological College North Eastern Hill University, Shillong Topic : Hripuiin Sakhuana A Nghawng Dan Topic : Hripui leh Mizona (Pandemic and Its Impact on Religious Practices) (Pandemic and Mizo Identity) NI THUMNA (DAY THRee) MAY 29 (INRINNI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Prof. -

Volume IX – 2 Spring 2017

CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal - UGC Approved) Vol : IX-2 Spring 2017 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X Prof. Zokaitluangi Editor in Chief Dean, School of Social Sciences, Mizoram University & Professor, Department of Psychology, Mizoram University SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA e-mail : [email protected] CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal - UGC approved) Vol : IX-2 Spring 2017 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X School of Social Editors Sciences- Convergence Editors Patron: Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Guidelines Editor in Chief: Professor Zokaitluangi, Dean , Shool of Social Sciences, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Archives (hard copy) Editorial boards: Prof. J.K. PatnaikDepartment of Political Science, MZU Vol: I - 1 Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Head Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: I - 2 Prof. O. Rosanga, Department of History & Ethnography, MZU Vol: II - 1 Prof. Lalrintluanga, Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: II - 2 Prof. Lalneihzovi, Department of Public Admn, MZU Vol: III - 1 Prof. C. Lalfamkima Varte, Head, Dept. of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 2 Prof. H.K. Laldinpuii Fente, Department of Psychology, MZU Vol: IV - 1 Prof. E. Kanagaraj, Department. of Social Work, MZU Vol: IV - 2 Prof. J. Doungel, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: V - 1 Prof. C. Devendiran, Head, Department of Social Work, MZU Vol: V - 2 Prof. K.V. Reddy, Head, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: VI - 1 Dr Lalngurliana Sailo, Head, Dept of Hist and Ethnography, MZU. Vol: VI - 2 Dr, R.K. Mohanty, Head, Department of Sociology, MZU Vol: VII - 1 Vol: VII - 1 National Advisory Board Members: Vol: VIII - 1 1. -

State of Economics of Education: a Study of Mizoram

Society & Change Vol. XIII, No.3, July-September 2019 ISSN: 1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) State of Economics of Education: A study of Mizoram Bidhu Kanti Das* Abstract Education is the backbone of any society and country. Our country got independence since long, but till today, it has not been able to achieve full literate. Few states have done well in this field, where the literacy rate is above the national average. Mizoram is one of them. Mizoram is the second largest literate state in India as per the census of 2011. It shows the seriousness of the state government as well as its education policy, which leads this state to become second literate state in India. Mizoram is one of the states of the North Eastern India, sharing borders with the states of Tripura, Assam, and Manipur and with the neighboring countries of Bangladesh and Myanmar. Since independence Mizoram was a district of Assam, and was counted as most backward area. The specified region was suffering from insurgent groups for freedom and statehood. Government of India declared this region as Union Territory in the year 1971. Mizoram became the 23rd state of India on 20 February 1987. The state covers an area of 2.1 million hectare and has a population of approximately 1.09 million. Around 60 per cent of the population of the state depends on agriculture. Mizoram has 8 districts with a total urban population of roughly 5.7 million and 5.2 million rural population as per the 2011 census. The year when Mizoram declared as Union territory 1971, it was enjoying a literacy rate of 53.8 percent, which was higher than the national average of 34.45; it further increased to 91.58 percent in 2011 census only after the state of Kerala which is 93.91 percent. -

Gorkhas of Mizoram: Migration and Settlement

Vol. V, Issue 2 (December 2019) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Gorkhas of Mizoram: Migration and Settlement Zoremsiami Pachuau * Hmingthanzuali † Abstract The Gorkhas were recruited in the British Indian Army after the Anglo-Nepal war. They soon proved to be loyal and faithful to the British. The British took great advantage of their loyalty and they became the main force for the British success in occupation especially in North East India. They came with the British and settled in Mizoram from the late 19 th century. They migrated and settled in different parts of the state. This paper attempts to trace the Gorkha migration since the Lushai Expeditions, how they settled permanently in a place so far from their own country. It also highlights how the British needed them to pacify the Mizo tribe in the initial period of their occupation. Keywords: Gorkhas, Lushai Expeditions, Migration, Mile 45 Dwarband Road Introduction The Mizo had no written language before the coming of the British. From generation to generation, the Mizo history, traditions, customs and practices were handed down in oral forms. The earliest written works about the Mizo were produced almost exclusively by westerners, mainly military and administrative officers who had some connection with Mizoram. This connection was related to the annexation and administration of the area by the British government (Gangte, 2018). The bulk of the early writings on Mizo were done by government officials. Another group of westerners who had done writings on Mizo were the Christian missionaries. It was in the late 1930s that Mizo started writing their own history, reconstructing largely from oral sources. -

“Integrated Design and Technical Development Project” for Bamboo

J-12012/279/2015-16/DS/NR/3081 dated 18th March, 2016 Integrated Design & Technical Development Project In Cane & Bamboo at Lengpui, Mizoram Organised By Export Promotion Council for Handicrafts Supported By Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) Documented by SANATHOI SINGHA NIFT Shillong The process of documenting the craft of Leingpui, Mizoram has been a unique experience and I feel privileged to have this opportunity. I would like to express my gratitude to all those who involved in this journey of project, as this documentation would not have been successful without their help &efforts. I extend my gratitude to Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) and Export Promotion Council For Handicraft (EPCH) for giving me this opportunity to study the craft and document the same and providing me with the necessary support & resources that were required in the process. A heartfelt thank to Mr. Rakesh Kumar, Executive Director( EPCH), Mr. R.K Vema (Director), Mrs. Rita Rohilla (Project Coordinator) & Ms. Amla Shrivastava (Head Designer), providing us all support and guidance which made us complete the project on time . They patiently guided me while I collected all the information and during the whole process of project. Finally , I would like to thank all artisans and mastercraftperson for their been interested on the project work and helping me to complete the project The study of cane & bamboo craft in Lengpui, Mizoram. After visiting the craft location and interacting with artisans , we have identified the major segment, techniques and process which are the basis of this documentation. The craft documentation is an attempt to understand the social & economic condition of the craft and its place. -

Rohmingmawii Front Final

ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX History and Historiography of Mizoram Mizo History Association September 2018 The main objective of this journal is to function as a mode of information and guidance for the scholars, researchers and historians and to provide a medium of exchange of ideas in Mizo history. © Mizo History Association, 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this journal may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronically or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher. ISSN : 0976 0202 Editor : Dr. Rohmingmawii The Editorial Board shall not be responsible for authenticity of data, results, views, and conclusions drawn by the contributors in this Journal. Price : Rs. 150/- Mizo History Association, Aizawl, Mizoram www. mizohistory.org Printed at the Samaritan Printer Mendus Building, Mission Veng, Aizawl ISSN : 0976 0202 HISTORICAL JOURNAL MIZORAM Vol. XIX September 2018 Editor Dr. Rohmingmawii Editorial Board Dr. Lalngurliana Sailo Dr. Samuel Vanlalthlanga Dr. Malsawmliana Dr. H. Vanlalhruaia Lalzarzova Dr. Lalnunpuii Ralte MIZO HISTORY ASSOCIATION: AIZAWL Office Bearers of Mizoram History Association (2017 – 2019) President : Prof. Sangkima Ex-Principal, Govt. Aizawl College Vice President : Prof. JV Hluna (Rtd) Pachhunga University College Secretary : Dr. Benjamin Ralte Govt. T Romana College Joint Secretary : Dr. Malsawmliana Govt. T Romana College Treasurer : Mrs. Judy Lalremruati Govt. Hrangbana College Patron : Prof. Darchhawna Kulikawn, Aizawl Executive Committee Members: Prof. O. Rosanga ............................... Mizoram University Mr. Ngurthankima Sailo ................. Govt. Hrangbana College Prof. C. Lalthlengliana .....................Govt. Aizawl West College Dr. Samuel VL Thlanga ...................Govt. Aizawl West College Mr.