Fractured Inheritance: Negotiating Memories of the Mizo Insurgency in India’S North Eastern Borderlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nandini Sundar

Interning Insurgent Populations: the buried histories of Indian Democracy Nandini Sundar Darzo (Mizoram) was one of the richest villages I have ever seen in this part of the world. There were ample stores of paddy, fowl and pigs. The villagers appeared well-fed and well-clad and most of them had some money in cash. We arrived in the village about ten in the morning. My orders were to get the villagers to collect whatever moveable property they could, and to set their own village on fire at seven in the evening. I also had orders to burn all the paddy and other grain that could not be carried away by the villagers to the new centre so as to keep food out of reach of the insurgents…. I somehow couldn’t do it. I called the Village Council President and told him that in three hours his men could hide all the excess paddy and other food grains in the caves and return for it after a few days under army escort. They concealed everything most efficiently. Night fell, and I had to persuade the villagers to come out and set fire to their homes. Nobody came out. Then I had to order my soldiers to enter every house and force the people out. Every man, woman and child who could walk came out with as much of his or her belongings and food as they could. But they wouldn’t set fire to their homes. Ultimately, I lit a torch myself and set fire to one of the houses. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Cultural Factors of Christianizing the Erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940)

Mizoram University Journal of Humanities & Social Sciences (A Bi-Annual Refereed Journal) Vol IV Issue 2, December 2018 ISSN: 2395-7352 eISSN:2581-6780 Cultural Factors of Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills (1890-1940) Zadingluaia Chinzah* Abstract Alexandrapore incident became a turning point in the history of the erstwhile Lushai Hills inhabited by simple hill people, living an egalitarian and communitarian life. The result of the encounter between two diverse and dissimilar cultures that were contrary to their form of living and thinking in every way imaginable resulted in the political annexation of the erstwhile Lushai Hills by the British colonial power,which was soon followed by the arrival of missionaries. In consolidating their hegemony and imperial designs, the missionaries were tools through which the hill tribes were to be pacified from raiding British territories. In the long run, this encounter resulted in the emergence and escalation of Christianity in such a massive scale that the hill tribes with their primal religious practices were converted into a westernised reli- gion. The paper problematizes claims for factors that led to the rise of Christianity by various Mizo Church historians, inclusive of the early generations and the emerging church historians. Most of these historians believed that waves of Revivalism was the major factor in Christianizing the erstwhile Lushai Hills though their perspectives or approach to their presumptions are different. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that cultural factors were integral to the rise and growth of Christianity in the erstwhile Lushai Hills during 1890-1940 as against the claims made before. Keywords : ‘Cultural Factors of Conversion,’ Tlawmngaihna, Thangchhuah, Pialral, Revivals. -

Web Directory of Mizoram

Web Directory of Mizoram Web Directory of Mizoram List of Tables 1. Apex Bodies in Mizoram 2. Legislative Assembly and Council 3: Districts (Official Website) 4: Directorate, Divisions/ Units/ Wings 5: Union Government 6. State Departments 7: Boards / Undertakings ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Web Directory of Mizoram Table 1. Apex Bodies in Mizoram Name Web Address Raj Bhawan, Mizoram https://rajbhavan.mizoram.gov.in/ Chief Minister of Mizoram https://cmonline.mizoram.gov.in/ Official Portal of Mizoram http://mizoram.nic.in/ Government State Election Commission (SEC), https://sec.mizoram.gov.in/ Mizoram Mizoram Finance Commission http://mizofincom.nic.in/ State Information Commission (SIC), https://mic.mizoram.gov.in/page/Profile.html Mizoram Mizoram Public Service Commission https://mpsc.mizoram.gov.in/ Table 2. Legislative Assembly and Council Name Web Address Legislative Assembly (Vidhan Sabha), Mizoram http://www.mizoramassembly.in/ Table 3: Districts (Official Website) S.N. Name Web Address 1 Aizawl http://aizawl.nic.in/ 2 Champhai http://champhai.nic.in/ 3 Kolasib http://kolasib.nic.in/ 4 Lawngtlai http://lawngtlai.nic.in/ 5 Lunglei http://lunglei.nic.in/ 6 Mamit http://mamit.nic.in/ 7 Saiha http://saiha.nic.in/ 8 Serchhip http://serchhip.nic.in/ ENVIS Centre on Himalayan Ecology, GBPIHED Web Directory of Mizoram Table 4: Directorate, Divisions/ Units/ Wings S.N. Name Web Address 1 Mizoram Remote Sensing Application Centre, Planning http://mirsac.nic.in/ Department, Mizorm 2 Office of the Deputy Commissioner, Aizawl -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

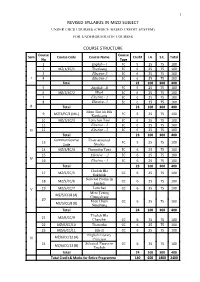

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

Mizoram Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Aizawl

State: Mizoram Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Aizawl 1.0 District Agriculture profile* 1.1 Agro-Climatic/Ecological Zone Agro Ecological Sub Region (ICAR) Purvachal (Eastern Range) (17.2) Humid Eastern Himalayan Region Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Eastern Himalayan Region Commission) Agro Climatic Zone (NARP) Sub Tropical Hill Zone List all the districts falling under the - NARP Zone* (*>50% area falling in the zone) Geographic coordinates of district Latitude Longitude Altitude headquarters head quarters 24°25’16.04’’ and 92°37’03.27’’ and 1,370 mtr. (4,492 ft) 23°18’17.78’’ N 93°11’45.69’’ E Name and address of the concerned ZRS/ ZARS/ RARS/ RRS/ RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district KVK, Aizawl, CAU, Selesih, Mizoram. with full address Name and address of the nearest Agromet AMFU, ICAR-RC Mizoram Centre, Kolasib Field Unit (AMFU, IMD) for agro- advisories in the Zone * Source: *Indicate source of data while furnishing information at different places in the district profile 1.2 Rainfall Normal RF(mm) Normal Rainy days Normal Onset Normal Cessation (number) ( specify week and (specify week and month) month) SW monsoon (June-Sep): 1633.28 120 1st week of June Last week of September NE Monsoon(Oct-Dec): 199 20 1st week of October 2nd week of December Winter (Jan- February) 135 4 1st Week of January 2nd week of February Summer (March-May) 377.1 9 1st week of March 4th week of May Annual 2344.38 233 1.3 Land use Geographical Cultivable Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other pattern of the area area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows district (latest agricultural use Misc. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:5 May 2015 ================================================================= The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. ================================================================= Abstract This paper discusses the problems of English Language Teaching and Learning in Mizoram, a state in India’s North-Eastern region. Since the State is evolving to be a monolingual state, more and more people tend to use only the local language, although skill in English language use is very highly valued by the people. Problems faced by both the teachers and the students are listed. Deficiencies in the syllabus as well as the textbooks are also pointed out. Some methods to improve the skills of both the teachers and students are suggested. Key words: English language teaching and learning, Mizoram schools, problems faced by students and teachers. 1. Introduction In order to understand the conditions and problems of teaching-learning English in Mizoram, it is important to delve into the background of Mizoram - its geographical location, the origin of the people (Mizo), the languages of the people, and the various cultures and customs practised by the people. How and when English Language Teaching (ELT) was started in Mizoram or how English is perceived, studied, seen and appreciated in Mizoram is an interesting question. Its remoteness and location also create problems for the learners. 2. Geographical Location Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:5 May 2015 Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram 173 Figure 1 : Map of Mizoram Mizoram is a mountainous region which became the 23rd State of the Indian Union in February, 1987. -

![Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0718/hripui-leh-literature-pandemic-and-literature-a-multidisciplinary-approach-may-27-29-2021-1550718.webp)

Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021

THREE DAY NATIONAL WEBINAR ON HRIPUI LEH LITERATURE [PANDEMIC AND LITERATURE : A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH] MAY 27-29, 2021 ORGANISeD BY DePArtMent of Mizo PACHHungA university College [A Constituent College of MizorAM university] ORGANIZING BODY PATRON Prof. H.Lalthanzara Principal, Pachhunga University College CO-PATRON CONveNeR CO-COORDINATORS enid H.Lalrammuani H.Laldinmawia Remlalthlamuanpuia Head & Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Dr. Zoramdinthara COORDINATOR Lalrotluanga Associate Professor Lalrammuana Sailo Assistant Professor Assistant Professor D r . L a l n u n p u i a Renthlei Assistant Professor Webinar Join Zoom Webinar@ 7:30 PM IST on May 27-29, 2021 For Registration WhatsApp Link Pachhunga Mizo Department Mizo Department : [email protected] Scan QR University College Instragram Pachhunga University [email protected] code for Channel mizo_department_puc College (Official) Whatsapp NI KHATNA (DAY ONe) MAY 27 (NINGANI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. vanlalnghaka Ralte B.Sc (Hons)., M.Sc, B.D., M.Th., D.Th. (Professor) Principal, Aizawl Theological College, Mizoram Keynote Speaker Prof. Malsawmliana Dr. Zothanchhingi Khiangte Department of History Assistant Professor, Department of English, Govt. T.Romana College, Aizawl, Mizoram Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Bodoland, India Topic : Hripui leh Mizo Literature – History Thlirna Atangin Topic :Literature Hring Chhuaktu Hripui (Pandemic and Mizo Literature – A Historical Approach) (Pandemic as a Source of Literature) NI HNIHNA (DAY TWO) MAY 28 (ZIRTAWP ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. H. vànlalruata Prof. vanlalnghaka Head, Christian Ministry & Communication Head, Department of Philosophy Aizawl Theological College North Eastern Hill University, Shillong Topic : Hripuiin Sakhuana A Nghawng Dan Topic : Hripui leh Mizona (Pandemic and Its Impact on Religious Practices) (Pandemic and Mizo Identity) NI THUMNA (DAY THRee) MAY 29 (INRINNI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Prof.