Rohmingmawii Front Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

Schedule for Selection of Below Poverty Line (Bpl) Families

SCHEDULE-I: SCHEDULE FOR SELECTION OF BELOW POVERTY LINE (BPL) FAMILIES STATE & STATE CODE : MIZORAM 15 NAME OF DISTRICT : CHAMPHAI DISTRICT CODE : 04 NAME OF BLOCK : NGOPA BLOCK CODE : 03 In Thlakhat awmdan Chhungkaw a ST/ Bank RUS Nu/ Village/ Village/ (katcha/ Voter ID Ration hotu chawhruala SC/ Account NO Pa hming Veng Veng Code No semi Card No Card No House in luah# hming pawisa nei/miIn Others No Chhungkaw pucca/ member zat lakluh zat pucca)@ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1967 Thangliana Khuala (L) 5 1700 Changzawl 10 22 01 11 FDV0198457 10097 ST 97009514505 1968 Lalzamlova Thanliana (L) 3 1700 Changzawl 10 24 01 11 FDV0219915 10068 ST 97000951035 1969 K Lalbiaksanga Lalbiaknunga (L) 2 1700 Changzawl 10 70 01 11 SSZ0022897 10019 ST 97003297000 1970 Lalnunhlima K Zabuanga (L) 7 3500 Changzawl 10 71 01 11 FDV0044826 10046 ST 25034017704 1971 Lalchhanhima Lalduhawma 5 2000 Changzawl 10 72 01 11 FDV0045047 10028 ST 97002524591 1972 Laldanga Ralkapa (L) 2 1700 Changzawl 10 75 01 11 FDV0049297 10030 ST 97002159377 1973 Hrangkima Tlanglawma (L) 6 2000 Changzawl 10 16 01 11 FDV0045039 10011 ST 97003793802 1974 Biakthangsanga Lalchhana 4 3000 Changzawl 10 80 01 11 FDV0062950 10003 ST 25034016438 1975 Lalsawmzuala Sapkhuma 1 2000 Changzawl 10 29 01 10 FDV0044545 10057 ST 97004199294 1976 Lalhmangaiha KT Hranga (L) 1 1500 Changzawl 10 60 01 11 FDV0044776 10034 ST 97004232030 1977 Sapkhuma Vanlalliana (L) 5 1700 Changzawl 10 7 01 11 FDV0045161 10093 ST 25034019553 1978 C Kapmawia Tlanglawma (L) 4 2500 Changzawl 10 16 01 11 FDV0044479 10104 -

A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language Michelle Arden San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arden, Michelle, "A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language" (2010). Master's Theses. 3744. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.v36r-dk3u https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Linguistics and Language Development San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Michelle J. Arden May 2010 © 2010 Michelle J. Arden ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Daniel Silverman Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Soteria Svorou Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Kenneth VanBik Department of Linguistics and Language Development ABSTRACT A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden This thesis presents a linguistic analysis of the Mara language, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in northwest Myanmar and in neighboring districts of India. -

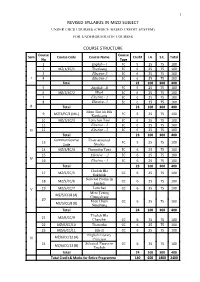

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

E:\Mizo Studies\Mizo Studies Se

Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 783 Vol. VI No. 4 October - December 2017 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 784 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VI No. 4 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) October - December 2017 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies Oct. - Dec., 2017 785 CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Folk Theatre and Drama of Mizo - Darchuailova Renthlei 2. Impact of Internet Use on the Family Life of Higher Secondary Students of Mizoram - Lynda Zohmingliani 3. The Bible and Study of Literature - Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. English Language: Its Importance & Problems of Learning in Mizoram - Brenda Laldingliani Sailo 5. Theme and Motif of LalthangfalaSailo’s HmangaihVangkhua Play - F. Lalnunpuii Mizo Section 1. Indopui Literature - F. Lalzuithanga 2. R. Zuala Thu leh Hla Thlirna (Literary Works of R. Zuala) - Lalzarzova 786 3. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram

================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:5 May 2015 ================================================================= The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. ================================================================= Abstract This paper discusses the problems of English Language Teaching and Learning in Mizoram, a state in India’s North-Eastern region. Since the State is evolving to be a monolingual state, more and more people tend to use only the local language, although skill in English language use is very highly valued by the people. Problems faced by both the teachers and the students are listed. Deficiencies in the syllabus as well as the textbooks are also pointed out. Some methods to improve the skills of both the teachers and students are suggested. Key words: English language teaching and learning, Mizoram schools, problems faced by students and teachers. 1. Introduction In order to understand the conditions and problems of teaching-learning English in Mizoram, it is important to delve into the background of Mizoram - its geographical location, the origin of the people (Mizo), the languages of the people, and the various cultures and customs practised by the people. How and when English Language Teaching (ELT) was started in Mizoram or how English is perceived, studied, seen and appreciated in Mizoram is an interesting question. Its remoteness and location also create problems for the learners. 2. Geographical Location Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:5 May 2015 Lalsangpuii, M.A. (English), B.Ed. The Problems of English Teaching and Learning in Mizoram 173 Figure 1 : Map of Mizoram Mizoram is a mountainous region which became the 23rd State of the Indian Union in February, 1987. -

The Mizoram.Gazette Publlshed by Autijority , /L " ' Vol

~c1. No. NB 907 ,The Mizoram.Gazette Publlshed by AutIJority , /l " ' Vol. XIX Aizawl Friday 30.1 U990 Agrahayana 9 S.B. 1912 Is!ue No, 48 h, Government of Mlzoram:;, , . -. " PART I') .. 1'~"O"lll!Jents.Postincs. Transfers, Powers. Leave and other. - " Personal Notices and Orders. ,;.* ., NOTIFICATION \ No.A.il20lil/l/90-P.!JRS(1l),u the 21st November.. 1990. In pursuance of Govt. of . hldial Ministry of'.Home Affairs Order No. 14020/55/90-UTS dt. 12. II. 90 or ,.., derin~ transfer/posting in respect of lAS officers: of AGMU Cadre. the Governor of Mizoram in the interest of Public service, is pleased to relieve Pu T.T. Joseph, lAS. (AGMU : 68). Financial Commissioner. Mizoram with effect from the date of handing over :,charge. , ., H. Lal Thlarnuana, Special Secretary to the Govt, of Mizoram, " !!, ,- f; ;, " ., -, .., No.A.19015/19!S9-PAR(R). the 26th November. 1990.•. The Governor of Mizoram J,s pl\'il:sed,to saaction 17 days Earned Leave with effect from 14.11.90 to 30.11.90 ta..Pi K. Lalkimi, -Supdt, Harne Department on private ground under the c.C.S (Leave) Rules, 1972 as amended from time to time. l,Certified, that the ,OlIjcei would have continued to hold the post of Superin- ,l4ndent J;>Ul for lIOI proceeding on leave. 3. Certified that the Officer would have continued to hold the same post and place from where she proceeded on leave and is authorised to draw during leave period the pay and allowances as admissible under the Rules. ..:r,··-l ' "- J;tq;$,\:J90IM84/8$"P~~).{th~ 29th November., IJ90. -

The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ·ORDINARY Published by Authority REGN. NO. N.E.-313 (MZ) Rs. 2/- per Issue VOL. XXX" Aizawl. Wednesday, 26.4.2006, Valsakha 6, S.E. 1928, Issue No. 103 NOTfCATION No. B. 14016/3/02-LAD/VC, the 18th April, 2006. In exercise of the powers co nferred by Section 7(1 )(2), Section 15 and Section 22(1) of the Lusbai Hills District (Village Councils) Act, 1953, as amended from time to time, the Gover- nor of Mizoram is pleased to approve Executive Body of the following Village Councils as shown in the enclosed Annexure within Cha mphai District. R. Sangliankhuma, Addl. Secretary, Local Administration Department. ANNEXURE CHAMPHAI DISTRICT -........------;-------- ----- 1 2 3 4 I4-KHAWBUNG Ale 1. Buang 1. Tinlinga· President 2. Thangchhinga Vice President & Treasurer 3. K. Lalzawngliana Secretary 4. ParlaV\oma Crier Ex-103/20C6 2 1 2 3 4 2. Bungzung J. Lalringzuala President 2. Lalpianfa Vice Pr�sider.t 3. La]zapa Trt:asurer 4. Lalhmingliana Secretary 5. Sangkhuma Crier 3. Bulfekzawl 1. Vanlalrin ga President 2. Chhunkhuma Vice Presifient 3. Chh un tb angvunga Treasurer 4. Laltums2nga Seer etary 5. I. F. }.'Iallga Crier 4. Chawngtui -E' Not yet formed Executive Body 5. Dungtlang 1. H. Laldin gliana President ., .. C. Zalawma Vice President 3. K. LaIthlamuana Treasurer 4. C. Lalzama Secretary 5. Kaprothanga Crier l 6. Farkawn 1. Lalslama President 2. Manghupa Vice President 3. Engm av. ia Treasurer 4. Ljansailova Secretary 5. Lalrawna Crier 7. Hruaikawn 1. C. Hranghleikapa President 2. Sangtinkulha Vice President 3. Sa ngtha n gpuia Treasurer 4 . -

![Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0718/hripui-leh-literature-pandemic-and-literature-a-multidisciplinary-approach-may-27-29-2021-1550718.webp)

Hripui Leh Literature [Pandemic and Literature : a Multidisciplinary Approach] May 27-29, 2021

THREE DAY NATIONAL WEBINAR ON HRIPUI LEH LITERATURE [PANDEMIC AND LITERATURE : A MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH] MAY 27-29, 2021 ORGANISeD BY DePArtMent of Mizo PACHHungA university College [A Constituent College of MizorAM university] ORGANIZING BODY PATRON Prof. H.Lalthanzara Principal, Pachhunga University College CO-PATRON CONveNeR CO-COORDINATORS enid H.Lalrammuani H.Laldinmawia Remlalthlamuanpuia Head & Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Dr. Zoramdinthara COORDINATOR Lalrotluanga Associate Professor Lalrammuana Sailo Assistant Professor Assistant Professor D r . L a l n u n p u i a Renthlei Assistant Professor Webinar Join Zoom Webinar@ 7:30 PM IST on May 27-29, 2021 For Registration WhatsApp Link Pachhunga Mizo Department Mizo Department : [email protected] Scan QR University College Instragram Pachhunga University [email protected] code for Channel mizo_department_puc College (Official) Whatsapp NI KHATNA (DAY ONe) MAY 27 (NINGANI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. vanlalnghaka Ralte B.Sc (Hons)., M.Sc, B.D., M.Th., D.Th. (Professor) Principal, Aizawl Theological College, Mizoram Keynote Speaker Prof. Malsawmliana Dr. Zothanchhingi Khiangte Department of History Assistant Professor, Department of English, Govt. T.Romana College, Aizawl, Mizoram Bodoland University, Kokrajhar, Bodoland, India Topic : Hripui leh Mizo Literature – History Thlirna Atangin Topic :Literature Hring Chhuaktu Hripui (Pandemic and Mizo Literature – A Historical Approach) (Pandemic as a Source of Literature) NI HNIHNA (DAY TWO) MAY 28 (ZIRTAWP ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Rev. Prof. H. vànlalruata Prof. vanlalnghaka Head, Christian Ministry & Communication Head, Department of Philosophy Aizawl Theological College North Eastern Hill University, Shillong Topic : Hripuiin Sakhuana A Nghawng Dan Topic : Hripui leh Mizona (Pandemic and Its Impact on Religious Practices) (Pandemic and Mizo Identity) NI THUMNA (DAY THRee) MAY 29 (INRINNI ZAN) @ 7:30 - 9:30 PM Prof. -

Mizoram Education (Transfer and Posting of School Teachers) Rules

The Mizoral111~Gazette~' EXTRA ORDINARY, ' ' •.. ,- '. ,I Published by Authoritv' REGN. NO. N.E.-313 (MZ) Rs. 2/- per Issue Vol. XXXV Aizawl, W~dnesday, 26.4.2006, Vaihsakha 6, S.E. 1928, Issue No. 104 No .A. 23022/5/2006 EDN, the 12th April, 2006. In exercise of th,e power con• erred by clause (xxxv) of sub-section (2) of sectidh 30 of the Mizoram Educa• tion Act, 2e03 (Act No. 5 of .2003), the Governor of Mizoram" is pleased to make the [allowing rules, namely :- . 1. SnORT TITLE? EXTENT AND COMMENCEMENT : (1) These Rules may be called the Mizoram Education (Transfer and . Posting of School Teachers) Rules, 2006, (2) It shall extend to the whole of Mizoram in respect of Elementary ,Educdtion and Secondary£ducation, except Chakllla Autonomous District, Lai Autonomou3 District and Mara Autohomous Dis• trict in respect of Elementary Education 'only. (3) These rul es shall com::: into force from til~ date of notificati on in the Mizoram Gazette. 2. IN THESE RULES, UNLESS THE CONTEXT OTHERWISE REQUIRES : ;- (1')' "Act" means MizoramEducati~n Act, 2003 (Act No. 5 of 2003) (2) ""Appropriate AuthoJity" shall mean the authority.as specified in Rule 9; (3) "District" means the jurisdiction area prescribed by tb.e Government of District Education Officer; (4) "Elementary School" means Primary Schools and Middle Schools~ (5) "Government" means the Government of Mizoram. (€i) "Sanctioned strellgth'>"me'<lDSth.t' number of posts 'of teachers as a 'particular School as Sanctiolled by the Government., -', , (-7) "Schedule" m6anl~a Schedul~ appended .,to these Rule·s; -l"fl' Ex-l04/2006 2 (8) "Secondary School" means High Schools and Higher Secondary Schools. -

“We Are Like Forgotten People”

“We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 2-56432-426-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org January 2009 2-56432-426-5 “We Are Like Forgotten People” The Chin People of Burma: Unsafe in Burma, Unprotected in India Map of Chin State, Burma, and Mizoram State, India .......................................................... 1 Map of the Original Territory of Ethnic Chin Tribes .............................................................. 2 I. Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 7 II. Background .................................................................................................................... 9 Brief Political History of the Chin ...................................................................................