Gorkhas of Mizoram: Migration and Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Mizo Studies Jan-March 2018

Mizo Studies January - March 2018 1 Vol. VII No. 1 January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies January - March 2018 MIZO STUDIES Vol. VII No. 1 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) January - March 2018 Editorial Board: Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Managing Editors - Prof. R. Thangvunga Prof. R.L. Thanmawia Circulation Managers - Dr. Ruth Lalremruati Ms. Gospel Lalramzauhvi Creative Editor - Mr. Lalzarzova © Dept. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal do not entertain legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 UGC Journal No. 47167 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl, Mizoram Mizo Studies January - March 2018 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Pioneer to remember - 5 English Section 1. The Two Gifted Blind Men - 7 Ruth V.L. Rinpuii 2. Aministrative Development in Mizoram - 19 Lalhmachhuana 3. Mizo Culture and Belief in the Light - 30 of Christianity Laltluangliana Khiangte 4. Mizo Folk Song at a Glance - 42 Lalhlimpuii 5. Ethnic Classifications, Pre-Colonial Settlement and Worldview of the Maras - 53 Dr. K. Robin 6. Oral Tradition: Nature and Characteristics of Mizo Folk Songs - 65 Dr. -

Carrying Capacity Analysis in Mizoram Tourism

Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January - June 2019), p. 30-37 Senhri Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies ISSN: 2456-3757 Vol. 04, No. 01 A Journal of Pachhunga University College Jan.-June, 2019 (A Peer Reviewed Journal) Open Access https://senhrijournal.ac.in DOI: 10.36110/sjms.2019.04.01.004 CARRYING CAPACITY ANALYSIS IN MIZORAM TOURISM Ghanashyam Deka 1,* & Rintluanga Pachuau2 1Department of Geography, Pachhunga University College, Aizawl, Mizoram 2Department of Geography & Resource Management, Mizoram University, Aizawl, Mizoram *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Ghanashyam Deka: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5246-9682 ABSTRACT Tourism Carrying Capacity was defined by the World Tourism Organization as the highest number of visitors that may visit a tourist spot at the same time, without causing damage of the natural, economic, environmental, cultural environment and no decline in the class of visitors' happiness. Carrying capacity is a concept that has been extensively applied in tourism and leisure studies since the 1960s, but its appearance can be date back to the 1930s. It may be viewed as an important thought in the eventual emergence of sustainability discussion, it has become less important in recent years as sustainability and its associated concepts have come to dominate planning on the management of tourism and its impacts. But the study of carrying capacity analysis is still an important tool to know the potentiality and future impact in tourism sector. Thus, up to some extent carrying capacity analysis is important study for tourist destinations and states like Mizoram. Mizoram is a small and young state with few thousands of visitors that visit the state every year. -

Beyond Labor History's Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast

Chapter 9 Beyond Labor History’s Comfort Zone? Labor Regimes in Northeast India, from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century Willem van Schendel 1 Introduction What is global labor history about? The turn toward a world-historical under- standing of labor relations has upset the traditional toolbox of labor histori- ans. Conventional concepts turn out to be insufficient to grasp the dizzying array and transmutations of labor relations beyond the North Atlantic region and the industrial world. Attempts to force these historical complexities into a conceptual straitjacket based on methodological nationalism and Eurocentric schemas typically fail.1 A truly “global” labor history needs to feel its way toward new perspectives and concepts. In his Workers of the World (2008), Marcel van der Linden pro- vides us with an excellent account of the theoretical and methodological chal- lenges ahead. He makes it very clear that labor historians need to leave their comfort zone. The task at hand is not to retreat into a further tightening of the theoretical rigging: “we should resist the temptation of an ‘empirically empty Grand Theory’ (to borrow C. Wright Mills’s expression); instead, we need to de- rive more accurate typologies from careful empirical study of labor relations.”2 This requires us to place “all historical processes in a larger context, no matter how geographically ‘small’ these processes are.”3 This chapter seeks to contribute to a more globalized labor history by con- sidering such “small” labor processes in a mountainous region of Asia. My aim is to show how these processes challenge us to explore beyond the comfort zone of “labor history,” and perhaps even beyond that of “global labor history” * International Institute of Social History and University of Amsterdam. -

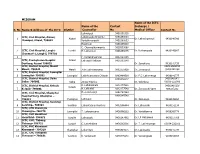

MIZORAM S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Name Of

MIZORAM Name of the ICTC Name of the Contact Incharge / S. No Name & Address of the ICTC District Counsellor No Medical Officer Contact No Lalhriatpuii 9436192315 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Aizawl, Lalbiakzuala Khiangte 9856450813 1 Aizawl Dr. Lalhmingmawii 9436140396 Dawrpui, Aizawl, 796001 Vanlalhmangaihi 9436380833 Hauhnuni 9436199610 C. Chawngthanmawia 9615593068 2 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Lunglei Lunglei H. Lalnunpuii 9436159875 Dr. Rothangpuia 9436146067 Chanmari-1, Lunglei, 796701 3 F. Vanlalchhanhimi 9612323306 ICTC, Presbyterian Hospital Aizawl Lalrozuali Rokhum 9436383340 Durtlang, Aizawl 796025 Dr. Sanghluna 9436141739 ICTC, District Hospital, Mamit 0389-2565393 4 Mamit- 796441 Mamit John Lalmuanawma 9862355928 Dr. Zosangpuii /9436141094 ICTC, District Hospital, Lawngtlai 5 Lawngtlai- 796891 Lawngtlai Lalchhuanvawra Chinzah 9863464519 Dr. P.C. Lalramenga 9436141777 ICTC, District Hospital, Saiha 9436378247 9436148247/ 6 Saiha- 796901 Saiha Zingia Hlychho Dr. Vabeilysa 03835-222006 ICTC, District Hospital, Kolasib R. Lalhmunliani 9612177649 9436141929/ Kolasib 7 Kolasib- 796081 H. Lalthafeli 9612177548 Dr. Zorinsangi Varte 986387282 ICTC, Civil Hospital, Champhai H. Zonunsangi 9862787484 Hospital Veng, Champhai – 9436145548 8 796321 Champhai Lalhlupuii Dr. Zatluanga 9436145254 ICTC, District Hospital, Serchhip 9 Serchhip– 796181 Serchhip Lalnuntluangi Renthlei 9863398484 Dr. Lalbiakdiki 9436151136 ICTC, CHC Chawngte 10 Chawngte– 796770 Lawngtlai T. Lalengmuana 9436966222 Dr. Vanlallawma 9436360778 ICTC, CHC Hnahthial 11 Hnahthial– 796571 -

Volume IX – 2 Spring 2017

CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal - UGC Approved) Vol : IX-2 Spring 2017 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X Prof. Zokaitluangi Editor in Chief Dean, School of Social Sciences, Mizoram University & Professor, Department of Psychology, Mizoram University SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MIZORAM UNIVERSITY (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA e-mail : [email protected] CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL SCIENTIST (A National Refereed Journal - UGC approved) Vol : IX-2 Spring 2017 ISSN No: 2230 - 956X School of Social Editors Sciences- Convergence Editors Patron: Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Guidelines Editor in Chief: Professor Zokaitluangi, Dean , Shool of Social Sciences, Mizoram University, Aizawl, India Archives (hard copy) Editorial boards: Prof. J.K. PatnaikDepartment of Political Science, MZU Vol: I - 1 Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Head Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: I - 2 Prof. O. Rosanga, Department of History & Ethnography, MZU Vol: II - 1 Prof. Lalrintluanga, Department of Public Administration, MZU Vol: II - 2 Prof. Lalneihzovi, Department of Public Admn, MZU Vol: III - 1 Prof. C. Lalfamkima Varte, Head, Dept. of Psychology, MZU Vol: III - 2 Prof. H.K. Laldinpuii Fente, Department of Psychology, MZU Vol: IV - 1 Prof. E. Kanagaraj, Department. of Social Work, MZU Vol: IV - 2 Prof. J. Doungel, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: V - 1 Prof. C. Devendiran, Head, Department of Social Work, MZU Vol: V - 2 Prof. K.V. Reddy, Head, Department of Political Science, MZU Vol: VI - 1 Dr Lalngurliana Sailo, Head, Dept of Hist and Ethnography, MZU. Vol: VI - 2 Dr, R.K. Mohanty, Head, Department of Sociology, MZU Vol: VII - 1 Vol: VII - 1 National Advisory Board Members: Vol: VIII - 1 1. -

State of Economics of Education: a Study of Mizoram

Society & Change Vol. XIII, No.3, July-September 2019 ISSN: 1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) State of Economics of Education: A study of Mizoram Bidhu Kanti Das* Abstract Education is the backbone of any society and country. Our country got independence since long, but till today, it has not been able to achieve full literate. Few states have done well in this field, where the literacy rate is above the national average. Mizoram is one of them. Mizoram is the second largest literate state in India as per the census of 2011. It shows the seriousness of the state government as well as its education policy, which leads this state to become second literate state in India. Mizoram is one of the states of the North Eastern India, sharing borders with the states of Tripura, Assam, and Manipur and with the neighboring countries of Bangladesh and Myanmar. Since independence Mizoram was a district of Assam, and was counted as most backward area. The specified region was suffering from insurgent groups for freedom and statehood. Government of India declared this region as Union Territory in the year 1971. Mizoram became the 23rd state of India on 20 February 1987. The state covers an area of 2.1 million hectare and has a population of approximately 1.09 million. Around 60 per cent of the population of the state depends on agriculture. Mizoram has 8 districts with a total urban population of roughly 5.7 million and 5.2 million rural population as per the 2011 census. The year when Mizoram declared as Union territory 1971, it was enjoying a literacy rate of 53.8 percent, which was higher than the national average of 34.45; it further increased to 91.58 percent in 2011 census only after the state of Kerala which is 93.91 percent. -

“Integrated Design and Technical Development Project” for Bamboo

J-12012/279/2015-16/DS/NR/3081 dated 18th March, 2016 Integrated Design & Technical Development Project In Cane & Bamboo at Lengpui, Mizoram Organised By Export Promotion Council for Handicrafts Supported By Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) Documented by SANATHOI SINGHA NIFT Shillong The process of documenting the craft of Leingpui, Mizoram has been a unique experience and I feel privileged to have this opportunity. I would like to express my gratitude to all those who involved in this journey of project, as this documentation would not have been successful without their help &efforts. I extend my gratitude to Development Commissioner (Handicrafts) and Export Promotion Council For Handicraft (EPCH) for giving me this opportunity to study the craft and document the same and providing me with the necessary support & resources that were required in the process. A heartfelt thank to Mr. Rakesh Kumar, Executive Director( EPCH), Mr. R.K Vema (Director), Mrs. Rita Rohilla (Project Coordinator) & Ms. Amla Shrivastava (Head Designer), providing us all support and guidance which made us complete the project on time . They patiently guided me while I collected all the information and during the whole process of project. Finally , I would like to thank all artisans and mastercraftperson for their been interested on the project work and helping me to complete the project The study of cane & bamboo craft in Lengpui, Mizoram. After visiting the craft location and interacting with artisans , we have identified the major segment, techniques and process which are the basis of this documentation. The craft documentation is an attempt to understand the social & economic condition of the craft and its place. -

A Study of Correlation Between the Mnf And

© 2018 JETIR August 2018, Volume 5, Issue 8 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) TRACING THE FLINCH OF INSURGENCY (A STUDY OF CORRELATION BETWEEN THE MNF AND ‘MAUTAM’ FAMINE IN MIZORAM) Dr Sakhawliana Assistant Professor, Department of Public Administration Government Kamalanagar College, Mizoram ABSTRACT Insurgency is causes, basically by political unwillingness of the administration. It is the call of the nations that the political track of different party’s should ensure nation building, and fixing the socio-economic menace of the general public. The prototyped imperialist, of premeditated coercive security and control of administration might not be viable to all sorts of establishments. Experience on the vital effects of the morale and psychology of the people can be seen in Mizoram, one of the North eastern states of India. This state has been under the profanity of insurgency for barely 20 years (1996-1986). It was said that after the famine cause by bamboo flowering, the philanthropic organisation of Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF) rechristened to form new political party of the Mizo National Front (MNF) and thrive for independence movement from the Indian Union. The hostility was brought by Mizo National Front (MNF) alias Mizo National Army (MNA), as its underground army wing, from one side and the Indian Army on the other. Over the year, the Indian Army and the MNA fought in tactical guerrilla warfare by using most sophisticated weapons of the 21st century. Therefore, it is impetus to unveil the insight of insurgency, in general, and the birth of the MNF for secession movement, in particular. -

Program of Study the Earliest Christian Missionaries to Mizoram, the State at the Southernmost Tip of India's Easternmost Fron

Program of Study The earliest Christian missionaries to Mizoram, the state at the southernmost tip of India’s easternmost frontier, are today regional heroes. Stone memorials of their visits rise up along roadsides, their portraits hang above hospital rooms, their hair clippings are preserved behind glass. Even schoolchildren’s sports teams are named in their honour. Histories of Mizoram place these British missionaries and administrators in the foreground, while Mizos remain two-dimensional stock characters in the background. This project aims not to follow the British missionaries of the mid-1890s but rather to face them, and to turn towards the Mizo as a corrective to our usual, British perspective on Mizoram’s contact with Christianity. The introduction to Mizoram of Western biomedicine features prominently in the writings of early missionaries. However, Mizo responses to it, whether as a technology of health or as a missionary tool of salvation, have not yet been investigated. Unlike the usual focus on religious ‘worldviews’, medicine provides us with a limited and concrete case study, but one just as intensely wrapped up in religiosity, both Christian and Mizo. As historian David Hardiman notes, mission medicine “was not carried out for a purely medical purpose, but used as a beneficent means to spread Christianity.”1 Indeed, in Mizoram it was at the missionaries’ medicine dispensary itself that the names of those wishing to become Christians were to be handed in.2 At the same time, author C. G. Verghese rightly points out that -

Ado)3Fl (Tisl 'S~Aol3 Aqiuewunooa Ieu!6Hjoh

'Ado)3fl (tisl 's~aoL3 AqIuewunooa ieu!6hJOh- Aq!PGS!lAGJt Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized . ........... Z,, .... V V '4% 4±. 4"~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~..... Public Disclosure Authorized V..~~~~~~~~~~...... "C..~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~..... Public Disclosure Authorized [ wflOA ...... 96V3 ;uow;~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~edao ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~jqn~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~...... WUJOZIWjo UQWUSWAO9~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~. .. .. I PREFACE The Mizoram State Roads Project includesaugmentation of the capacityand structural upgradationof selectedroad network in the state. A total of 185.71kmroads will be improved/upgraded,and major maintenanceworks will be carriedout on 518.615kmroads, in 2 Phases.The project was preparedby the ProjectCo-ordinating Consultants (PCC)', on behalf of the PWD, Mizoram.As part of the project preparation,environmental/social assessmentswere carriedout, as requiredby the WorldBank and the Governmentof India. In accordanceto the requirementsof the WorldBank, the environmental/socialassessments (and the outputs) had been subjectedto an IndependentReview. The independentreview 2 evaluatedthe EA processesand outputsin the projectto verify that (a) the EA had been carriedout withoutany biasor influencefrom the projectproponent and/or the PCC,(b) the EA/SAhad beenable to influenceplanning and design of the project;and (c) the outputs, especiallythe mitigation/managementmeasures identified in the EA/SA processesare | adequatefor the -

Serchhip DDMP

TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Chapter I: Introduction 1-10 1.1 Aims and Objectives of the DDMP 1.2 Authority for DDMP: Disaster Management Act 2005 (DM Act 1.3 Evolution of DDMP in brief 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibilities 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework 1.6 Approval Mechanism of DDMP 1.7 Plan review and updation : Periodicity Chapter 2: Hazard, Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (HVCRA) 11-31 2.1.1 Socio – economic profile of the district 2.1.2 Matrix of Past disasters in the district 2.1.2.2 Report of Natural Calamities (2016 – 2017) 2.1.2.3 Life and cattle loss 2.1.2.4 Damage to infrastructure 2.1.2.5 Economic losses . 2.1.2.6Environmental degradation, livelihood restoration and livestock management 2.1.3.Hazard Risk Vulnerability Assessment (HVCRA) 2.1.3.1 Authority/Agency that carried out HVCRA Chapter 3: Institutional arrangements for Disaster Management 32- 61 3.3.1 DM organizational structure at the national level, 3.3.2 DM organizational structure at the state level including IRS in the State 3.3.3 DM organizational structure at the district level 3.3.3.1 District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA) 3.3.3.2 District Crisis Management Group (CMG) 3.3.3.3 District Disaster Management Committee and Task Forces. 3.3.3.4 IRS in the District. 3.3.3.5 DEOC setup and facilities available in the district 3.3.3.6 Alternate EOC if available and its location 3.3.4 Public-Private Partnership 3.3.4.1 Public and private emergency service facilities available in the district 3.3.5 Forecasting and warning agencies Chapter 4: Prevention and Mitigation Measures 63-72 4.1 Prevention Measures 4.1.1 Specific projects proposed for preventing the disasters.