Constructing the Identity of Mizo Women in Selected Mizo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

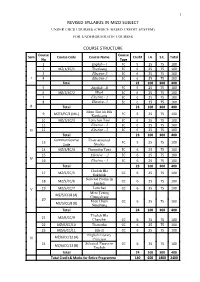

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

TDC Syllabus Under CBCS for Persian, Urdu, Bodo, Mizo, Nepali and Hmar

Proposed Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (Honours) Persian 1 B.A. (Hons.): Persian is not merely a language but the life line of inter-disciplinary studies in the present global scenario as it is a fast growing subject being studied and offered as a major subject in the higher ranking educational institutions at world level. In view of it the proposed course is developed with the aims to equip the students with the linguistic, language and literary skills for meeting the growing demand of this discipline and promoting skill based education. The proposed course will facilitate self-discovery in the students and ensure their enthusiastic and effective participation in responding to the needs and challenges of society. The course is prepared with the objectives to enable students in developing skills and competencies needed for meeting the challenges being faced by our present society and requisite essential demand of harmony amongst human society as well and for his/her self-growth effectively. Therefore, this syllabus which can be opted by other Persian Departments of all Universities where teaching of Persian is being imparted is compatible and prepared keeping in mind the changing nature of the society, demand of the language skills to be carried with in the form of competencies by the students to understand and respond to the same efficiently and effectively. Teaching Method: The proposed course is aimed to inculcate and equip the students with three major components of Persian Language and Literature and Persianate culture which include the Indo-Persianate culture, the vital portion of our secular heritage. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

New Additions to Parliament Library

NEW ADDITIONS TO PARLIAMENT LIBRARY English 000 GENERALITIES 1 Crouch, James S. A bibliography of Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy / James S. Crouch.-- New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2002. 430p.; 25cm. ISBN : 81-7304-428-7. 016.828 CRO-c C73781 Price : RS.**1000.00 2 Mathew, Mammen, ed. Manorama Yearbook 2015 / edited by Mammen Mathew.-- Kottayam: Malayala Manorama, 2015. 1038p.; 20cm. R 030 MAT-m B209257(Ref.) Price : RS.***250.00 3 McWhirter, Norris Guinness book of world records / Norris McWhirter and Ross McWhirter.-- New York: Bantam Press, 1974. 672p.: plates; 19cm. R 032.02 GUI B80309(Ref.) Price : RS.***895.00 4 General.-- [s.l.]: [s.n.], [2015]. v.p.; 33cm. Multilingual. R 070.403 GEN OB4138(2) (Ref.) 5 Rodrigues, Usha M. India news media: from observer to participant / Usha M. Rodrigues and Maya Ranganathan.-- New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2015. xiv, 240p.: plates; 22cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN : 978-93-515-0050-6. 079.54 USH-in B209246 Price : RS.***895.00 6 Aiyar, V.R. Krishna Letters and lectures of an anguished soul / V.R. Krishna Iyer.-- Madurai: Society for Community Organisation Trust , 2013. vi, 155p.; 21cm. 080 AIY-l C73627 7 Chawla, Bindu Conversations with Pandit Amarnath / Bindu Chawla.-- New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 2004. xiii, 173p.: plates; 25cm. ISBN : 81-85503-07-9. 080 AMA-b C73799 Price : RS.***435.00 8 Champions: the world's greatest cricketers speak: conversations with Mike Coward.-- New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014. x, 243p.: plates; 24cm. First published by Allen and Unwin Australia, 2013. -

National Affairs

NATIONAL AFFAIRS Prithvi II Missile Successfully Testifi ed India on November 19, 2006 successfully test-fi red the nuclear-capsule airforce version of the surface-to- surface Prithvi II missile from a defence base in Orissa. It is designed for battlefi eld use agaisnt troops or armoured formations. India-China Relations China’s President Hu Jintao arrived in India on November 20, 2006 on a fourday visit that was aimed at consolidating trade and bilateral cooperation as well as ending years of mistrust between the two Asian giants. Hu, the fi rst Chinese head of state to visit India in more than a decade, was received at the airport in New Delhi by India’s Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Science and Technology Minister Kapil Sibal. The Chinese leader held talks with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in Delhi on a range of bilateral issues, including commercial and economic cooperation. The two also reviewed progress in resolving the protracted border dispute between the two countries. After the summit, India and China signed various pacts in areas such as trade, economics, health and education and added “more substance” to their strategic partnership in the context of the evolving global order. India and China signed as many as 13 bilateral agreements in the presence of visiting Chinese President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The fi rst three were signed by External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing. They are: (1) Protocol on the establishment of Consulates-General at Guangzhou and Kolkata. It provides for an Indian Consulate- General in Guangzhou with its consular district covering seven Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hainan, Yunnan, Sichuan and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. -

E-Newsletter

ALL-INDIA WRITERS' MEET 24-25 March 2018, Kohima, Nagaland In collaboration with Nagaland University, a two-day All-India Writers' Meet was organized on 24-25 March 2018 at Kohima, Nagaland. For the first time the Akademi organized a national-level programme at Nagaland. The very objective of this mega event was a challenge to bring reputed writers from various languages and from different parts of the country to Nagaland and usher in a new environment for the Naga writers. This was an opportunity to bring together different languages of the country with the languages of Nagaland. Dr K. Sreenivasarao, Secretary, Sahitya Akademi, while welcoming the delegates, encouraged the native writers to bring out the beautiful Naga cultural and literary traditions so as to make them known to others. Dr D. Kuolie, General Council Member, Sahitya Akademi, asserted that the idea of organizing this event was a constructive endeavour, an attempt to bring the writers of the country together. Professor Temsula Ao, eminent English writer, delivered the keynote address and observed that the Nagas have a rich oral tradition, but modern generation has lost many knowledgeable story-tellers and folk-singers, which she considered as the greatest casualties of progress and development of the society. She encouraged and appreciated the younger generation to create a new tradition where the soul of oral tradition resonates with new vigour. Prof. Temsula Ao delivering the keynote address Dr Madhav Kaushik speaking during the event Professor Ramesh C. Gupta, Pro Vice-Chancellor, Nagaland University, gave a brief historical account on the institutionalization of Sahitya Akademi and highlighted the aspiration of the pioneers. -

DEPARTMENT of ASSAMESE DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY Course Structure of MA in Assamese Under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS)

1 DEPARTMENT OF ASSAMESE DIBRUGARH UNIVERSITY Course Structure of MA in Assamese under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) Course Structure of MA in Assamese under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) as approved by the Board of Studies in Assamese held on 20/03/2019 and the Academic Council in its meeting held on ………………… The Post Graduate Programme in Assamese shall be of four semesters covering two academic years. Students have to register themselves as per the prevailing CBCS guidelines of Dibrugarh University. 2 COMPLETE COURSE STRUCTURE M.A. in Assamese (CBCS), 2019 FIRST SEMESTER CORE Course No Title of the Paper Credit Teacher C1001 The Assamese Language : Background, Formation 4 SMC and Development C1002 Trend and Tendencies of Assamese Literature 4 JKB C1003 Literary Theory and Criticism (Eastern) 4 NKH DISCIPLINE SPECIFIC ELECTIVE (ANY ONE) D1001 Introduction to Linguistics 4 AK D1002 Sociology of Assamese Literature 4 NMB D1003 Introduction to Indian Literature 4 SK/NMB D1004 Varieties of Assamese Language 4 DK ABILITY ENHANCEMENT COURSE A1001 Spoken English 2 PB SECOND SEMESTER CORE Course No Title of the Paper Credit Teacher C2001 Studies on Culture of Assam 4 SB C2002 Structure of Assamese 4 DK C2003 Literary Theory and Criticism (Western) 4 PB DISCIPLINE SPECIFIC ELECTIVE (ANY ONE) D2001 Study of Assamese Drama 4 JKB D2002 Assamese Literature and Culture in New Media : 4 SMC Trend and Tendencies D2003 Sanskrit Literature 4 NKH D2004 Approaches to Linguistic Studies 4 SD GENERIC ELECTIVE (ANY ONE) G2001 Communicative Assamese -

E:\Pendrive\Last Edited Mizo St

Mizo Studies July - September 2016 125 Vol. V No. 3 July - September 2016 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 126 Mizo Studies July - September 2016 MIZO STUDIES Vol. V No. 3 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) July - September, 2016 © Deptt. of Mizo, Mizoram University Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief : Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Editor : Prof. R.Thangvunga Circulation Managers : Mr Lalsangzuala : Mr. K.Lalnunhlima No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors and the Editorial Board and publisher of this Journal are not accountable for the articles published in this journal. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies July - September 2016 127 Mizo Studies V.3 ISSN:2319-6041 © Dept. of Mizo,MZU CONTENTS Editorial English Section 1. Henry Zodinliana Pachuau, Impact of Insurgency on Women and Children in the North-East. ...........................7 2. J.Zahluna, Emergence of Political Party in Mizoram..........13 3. Lalhriatpuii, Demographic Impact and Security Implications of Illegal Immigrations into Northeast India....23 4. R.Thangvunga, Trickster Tales in Mizo Folklore...............33 5. Lynda Zohmingliani & PC Lalremruati, Environmental Aware- ness of Elementary School Students and Suggested Measures to Improve Teaching ....................... Mizo Section 1. V.Lalnunmnawia, Pi Pute leh Sakei. 2. H.Lalbiakzuali, Zikpuii Pa’n Khuarel (Nature) a Thlir Dan. -

Mizo ( Code : 098) Class - Ix 2019 – 2020

MIZO ( CODE : 098) CLASS - IX 2019 – 2020 TYPE OF NO. OF SECTION DETAILS OF TOPICS/ CHAPTERS QUESTIONS QUESTIONS MARKS Section - A One unseen passage of minimum 500 S.A. 6 2X6=12 Reading words. There will be six general questions of two Comprehension marks each from the passage and three grammar (15 marks) based question of 01 mark each V.S.A. 3 1X3=3 L.A. 1 4X1=4 Section - B Parts of speech : (Noun, Pronoun, Verb, Grammar Adjective, Adverb, Postposition, S.A. 3 2X3=6 (15 marks) Conjunction, Interjection) V.S.A. 5 1X5=5 1. Essay Writing L.A. 1 10X1=10 Section - C 2. Translation from English to Mizo L.A. 1 5X1=5 Composition (25 marks) 3. Short Story Writing L.A. 1 5X1=5 4. Letter Writing Personal, formal & informal L.A. 1 5X1=5 Poetry to be studied 1. Ka damlai thlipui - Patea 2. Lei mite hun bi - Rokunga 3. Lenkawl Engin Tlang Dum Dur- Aithulha L.A. 1 4X1=4 4. Kan Dam Chhung Ni - P.S.Chawngthu S.A. 2 2X2=4 5. Khuavel ila Chhing Ngei Ang- V.Thangzama V.S.A. 4 1X4=4 Section - D 6. Sekibuhchhuak - Zirsangzela Literature 7. Vau Thla - Lalsangzuali Sailo (25 marks) 8. Kar a Hla - Lalhmingthanga Prose to be studied 1. Zan - James Dokhuma 2. Huaina - R.H. Rokunga 3. Dawhtheihna - R.L.Thanmawia L.A. 1 4X1=4 4. Mihring dikna leh chanvo - S.A. 2 2X2=4 Dr.C.Lalhmanmawia 5. Kut Hnathawh Hlutzia - J.F.Laldailova V.S.A. 5 1X5=5 6. -

After Decades of Silence Voices from Mizoram a Brief Review of Mizo Literature

After DeAcadefter Des ofcade Silencs ofe S: ilencVoicese: VoEmericesge E merge in Mizorina mM izor am Brief ReviewBrief o fR Mizeviewo Liter of Mizatureo Liter ature Margaret Ch. ZamMaarg anda retLalaw Ch.m Zampuiaa Vanchiand Lalawiau mpuia Vanchiiau Centre for NorthCentre East f orStudi Northes andEast Po Studiolicye Reses anda rch,Poolic Newy Rese Delhiarch, New Delhi With support fWitromh Heinsupportrich fBromöll FHeinoundationrich Bö,ll New Foundation Delhi , New Delhi 1 1 AFTER DECADES OF SILENCE Voices from Mizoram A Brief Review of Mizo Literature Margaret Ch. Zama and C. Lalawmpuia Vanchiau AFTER DECADES OF SILENCE Voices from Mizoram A Brief Review of Mizo Literature Margaret Ch. Zama and C. Lalawmpuia Vanchiau Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research with support from the Heinrich Böll Stiftung, New Delhi AMBER BOOKS D-9, Defence Colony, New Delhi-110024 Email: [email protected] After Decades of Silence: Voices from Mizoram A Brief Report of Mizo Literature was first published in 2016 by Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research (C-NES), New Delhi B-378 Chittaranjan Park New Delhi 110019 Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research (C-NES), Guwahati House No 25, Bhaskar Nagar RG Barua Road Guwahati 781021 With support from the Heinrich Böll Stiftung (HBF) C 20, First Floor, Qutub Institutional Area New Delhi 110016 © Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, 2016 ISBN: 978-93-81722-26-8 Printed at FACET (D-9, Defence Colony, New Delhi - 1100024) This book is the result of a research project titled ‘After Decades of Silence: Voices from Mizoram’ conducted by C-NES and supported by HBF, New Delhi Photo credit: Mr. -

Colonized by the Dark Whites Freed by Grace: an Analysis of the First Two Mizo Written Narratives

NEW LITERARIA- An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities Volume 1, No. 2, November-December, 2020, PP 207-216 ISSN: 2582-7375 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.48189/nl.2020.v01i2.0016 www.newliteraria.com Colonized by the Dark Whites Freed by Grace: An Analysis of the First Two Mizo Written Narratives Lalnienga Bawitlung & K.C. Lalthlamuani Abstract This paper attempts to study the colonial influence that destroyed the balance between the lives of Mizo men and women– the people who made their entry into the forested mountainous regions of Northeast India, later known as Mizoram in the late 17th century– through the narratives of L. Biakliana (1918-1941), author of the first Mizo novel Hawilopari (1936) and the first Mizo short story “Lali” (1937). The life of a Mizo woman was more burdensome in the last decade of the 19th century and first three decades of the 20th century than at any given point of time. The acuteness of their sufferings in the early 20th century under patriarchal society is clearly described in “Lali”, wherein they are likened to slaves and commodities that can be bargained and sold. However, a very different picture is depicted in Hawilopari, where there does not seem to be any differentiation in terms of gender. Women felt secure under the men’s guidance before the appearance of the white men, who, with better weapons ruled the land prohibiting raiding and head-hunting whereas they themselves practiced it. For a short time even the emergence of the Missionaries was a great pain to the men because they had to put away their paganistic ritualistic practices.