E:\Dahkhawm\Mizo Studies Oct- D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority RNI No. 27009/1973 Postal Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) 2006-2008 VOL - XLV Aizawl, Friday 23.9.2016 Asvina 1, S.E. 1938, Issue No. 361 NOTIFICATION No.B.11035/60/2014-EDN, the 21st September, 2016. In partial modification of this Department’s Notification of even No. dated 3.3.2015, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to modify the Mizo Language Committee (MLC) under Mizoram Board of School Education as shown below :- 1. Chairman, MBSE Ex-Officio Chairman 2. Secretary, MBSE Ex-Officio Secretary 3. Director(Academic), MBSE Co-ordinator 4. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Mission Veng, Aizawl. Member 5. Pu KMS Dawngliana, Serkawn, Lunglei Member 6. Prof. Lalthangfala Sailo, Chaltlang, Dawrkawn. Member 7. Prof. Darchhawna, Kulikawn, Aizawl. Member 8. Pu C.Sangzuala, Ex-MLA, Chaltlang Dawrkawn. Member 9. Revd Chuauthuama, Ramhlun Venglai, Aizawl. Member 10. Dr.Lalzuia Colney, Kanan Veng, Aizawl. Member 11. Pu Chhuanliana, Bethlehem Vengthlang, Aizawl. Member 12. Pu C.Chhuanvawra, Tuikhuahtlang, Aizawl. Member 13. Pu R.Vanramchhuanga, Ramhlun Vengthar, Aizawl. Member 14. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Ramhlun South, Aizawl. Member 15. Pu B.Lalthangliana, Chhinga Veng, Aizawl. Member 16. Pu R.Rozika, Electric Veng, Lunglei. Member 17. Pu H.Ronghaka, Vaivakawn, Aizawl. Member 18. Pu Darchuailova Renthlei, Chaltlang Ruam Veng. Member 19. Pu Lalrinawma, Venghlui, Aizawl. Member 20. Pu R.Lallianzuala, Chanmari, Aizawl. Member 21. Prof. R.Thangvunga, Kanan Veng, Aizawl. Member 22. Pu R.Lalrawna, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Member 23. Pu Rozama Chawngthu, Mission Vengthlang, Aizawl. Member 24. Joint Director(S), Directorate of School Education. -

Vol III Issue I June2017

Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) MIZORAM UNIVERSITY NAAC Accredited Grade ‘A’ (2014) (A CENTRAL UNIVERSITY) TANHRIL, AIZAWL – 796004 MIZORAM, INDIA i . ii Vol III Issue 1 June 2017 ISSN 2395-7352 MIZORAM UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL SCIENCES (A National Refereed Bi-Annual Journal) Chief Editor Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama Editor Prof. J. Doungel iii Patron : Prof. Lianzela, Vice Chancellor, Mizoram University Advisor : Mr. C. Zothankhuma, IDAS, Registrar, Mizoram University Editorial Board Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Dept. of English, Chief Editor Prof. Srinibas Pathi, Dept. of Public Administration, Member Prof. NVR Jyoti Kumar, Dept. of Commerce, Member Prof. Lalhmasai Chuaungo, Dept. of Education, Member Prof. Sanjay Kumar, Dept. of Hindi, Member Prof. J. Doungel, Dept. of Political Science, Member Dr. V. Ratnamala, Dept. of Jour & Mass Communication, Member Dr. Hmingthanzuali, Dept. of History & Ethnography, Member Mr. Lalsangzuala, Dept. of Mizo, Member National Advisory Board Prof. Sukadev Nanda, Former Vice Chancellor of FM University, Bhubaneswar Prof. K. Rama Mohana Rao, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam Prof. K. C. Baral, Director, EFLU, Shillong Prof. Arun Hota, West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal Dr. Sunil Behari Mohanty, Editor, Journal of AIAER, Puducherry Prof. Joy. L. Pachuau, JNU, New Delhi Prof. G. Ravindran, University of Madras, Chennai Prof. Ksh. Bimola Devi, Manipur University, Imphal iv CONTENTS From the Desk of the Chief Editor vii Conceptualizing Traditions and Traditional Institutions in Northeast India 1 - T.T. Haokip Electoral Reform: A Lesson from Mizoram People Forum (MPF) 11 - Joseph C. -

Volume III Issue II Dec2016

MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies MZU JOURNAL OF LITERATURE AND CULTURAL STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Volume III Issue 2 ISSN:2348-1188 Editor-in-Chief : Prof. Margaret L. Pachuau Editor : Dr. K.C. Lalthlamuani Editorial Board: Prof. Margaret Ch.Zama Prof. Sarangadhar Baral Dr. Lalrindiki T. Fanai Dr. Cherrie L. Chhangte Dr. Kristina Z. Zama Dr. Th. Dhanajit Singh Advisory Board: Prof.Jharna Sanyal,University of Calcutta Prof.Ranjit Devgoswami,Gauhati University Prof.Desmond Kharmawphlang,NEHU Shillong Prof.B.K.Danta,Tezpur University Prof.R.Thangvunga,Mizoram University Prof.R.L.Thanmawia, Mizoram University Published by the Department of English, Mizoram University. 1 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies 2 MZU Journal of Literature and Cultural Studies EDITORIAL It is with great pleasure that I write the editorial of this issue of MZU Journal of Literature and Culture Studies. Initially beginning with an annual publication, a new era unfolds with regards to the procedures and regulations incorporated in the present publication. The second volume to be published this year and within a short period of time, I am fortunate with the overwhelming response in the form of articles received. This issue covers various aspects of the political, social and cultural scenario of the North-East as well as various academic paradigms from across the country and abroad. Starting with The silenced Voices from the Northeast of India which shows women as the worst sufferers in any form of violence, female characters seeking survival are also depicted in Morrison’s, Deshpande’s and Arundhati Roy’s fictions. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Understanding the Breakdown in North East India: Explorations in State-Society Relations

Working Paper Series ISSN 1470-2320 2007 No.07-83 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan Published: May 2007 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Web site: www.lse.ac.uk/depts/destin 1 Understanding the breakdown in North East India: Explorations in state-society relations M. Sajjad Hassan DESTIN, London School of Economics 1. Introduction Northeastern India – a compact region made up of seven sub-national states1- has historically seen high levels of violence, stemming mostly from ethnic and separatist conflicts. It was among the first of the regions, to demonstrate, on the attainment of Independence, signs of severe political crisis in the form of nationalist movements. This has translated into a string of armed separatist movements and inter-group ethnic conflicts that have become the enduring feature of its politics. Separatist rebellions broke out first in Naga Hills district of erstwhile Assam State, to be followed by similar armed movement in the Lushai Hills district of that State. Soon secessionism overtook Assam proper and in Tripura and Manipur. Of late Meghalaya and Arunachal Pradesh have joined the list of States that are characterised as unstable and violent. Despite the attempts of both the state and society, many of these violent movements have continued to this day with serious implications for the welfare of citizens (Table 1). Besides separatist violence, inter-group ethnic clashes have been frequent and have taken a heavy toll of life and property.2 Ethnic violence exists alongside inter-ethnic contestations, over resources and opportunities, in which the state finds itself pulled in different directions, with little ability to provide solutions. -

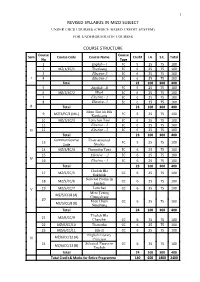

Mizo Subject Under Cbcs Courses (Choice Based Credit System) for Undergraduate Courses

1 REVISED SYLLABUS IN MIZO SUBJECT UNDER CBCS COURSES (CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM) FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSES COURSE STRUCTURE Course Course Sem Course Code Course Name Credit I.A. S.E. Total No Type 1 English – I FC 5 25 75 100 2 MZ/1/EC/1 Thutluang EC 6 25 75 100 3 Elective-2 EC 6 25 75 100 I 4 Elective-3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 5 English - II FC 5 25 75 100 6 MZ/2/EC/2 Hla-I EC 6 25 75 100 7 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 8 Elective- 3 EC 6 25 75 100 II Total 23 100 300 400 Mizo Thu leh Hla 9 MZ/3/FC/3 (MIL) FC 5 25 75 100 Kamkeuna 10 MZ/3/EC/3 Lemchan Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 11 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 III 12 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Common Course Environmental 13 FC 5 25 75 100 Code Studies 14 MZ/4/EC/4 Thawnthu Tawi EC 6 25 75 100 15 Elective - 2 EC 6 25 75 100 IV 16 Elective - 3 EC 6 25 75 100 Total 23 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 17 MZ/5/CC/5 CC 6 25 75 100 Sukthlek Selected Poems in 18 MZ/5/CC/6 CC 6 25 75 100 English V 19 MZ/5/CC/7 Lemchan CC 6 25 75 100 Mizo |awng MZ/5/CC/8 (A) Chungchang 20 Mizo Hnam CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/5/CC/8 (B) Nunphung Total 24 100 300 400 Thu leh Hla 21 MZ/6/CC/9 Chanchin CC 6 25 75 100 22 MZ/6/CC/10 Thawnthu CC 6 25 75 100 23 MZ/6/CC/11 Hla-II CC 6 25 75 100 English Literary MZ/6/CC/12 (A) VI Criticism 24 Selected Essays in CC 6 25 75 100 MZ/6/CC/12 (B) English Total 24 100 300 400 Total Credit & Marks for Entire Programme 140 600 1800 2400 2 DETAILED COURSE CONTENTS SEMESTER-I Course : MZ/1/EC/1 - Thutluang ( Prose & Essays) Unit I : 1) Pu Hanga Leilet Veng - C. -

SOP Return Thar 15.05.2020

No.B. L3O21/ 1O5 l2O2O-DMR GOVERNMENT OF MIZORAM DISASTER MANAGEMENT & REHABILITATION DEPARTMENT **** Aizawl, the 75th of Mag, 2O2O CIRCULAR Mtzoratn mi leh sa India ram hmundanga tangkangte 1o haw dan tur ssCOVID- leh 1o dawnsawn dan turah mumal zawka hma lak anih theih nan 79 Lockdown Aaanga Mizoram Mi leh Sa, Mizoram Pautna Tangkhangte lo Hana Dan Tttr Kaihhtttaina Siamthoit (Reaised Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) For Return of Permanent Residents of Mizorcrm Stranded Outside the State due to Couid-79 Lockdourin)" chu heta thiltel ang hian siamthat a ni a, hemi chungchanga hmalatute zawm atan tihchhuah a ni e. sd/-LALBIAKSANGI Secretary to the Govt. of Mizoram Disaster Management & Rehabilitation Department Memo No.B.73O27flO5/2O2O-DMR : Aizaul, the 75th of Mag, 2O2O Copy to: 1. P.S. to Chief Minister,Mizoram for information. 2. P.S. to Deputy Chief Minister, Mizoram 3. P.S. to Speaker, Mtzorasrt 4. P.S. to all Ministers/Ministers of State/Deputy Speaker/Vice- Chairman/Deputy Govt. Chief Whip, Mizorarn. 5. Sr. P.P.S to Chief Secretary, Govt. of Mtzora.m. 6. P.P.S. to Addl. Chief Secretary to Chief Minister, Govt. of M2oram. 7. A11 Principal Secretaries/ Commissioner/ Secretaries/ Special Secretaries, Govt. of Mworam. 8. Director General of Police, Mizotam 9. Administrative Heads of Departments, Government of Mizoram Secretary of all Constitutional & Statutory Bodies , Mtzotam. 10. Chairpersons, Task Group on Medicine & Medical Equipments/ Quarantine Facilities/Commodities & Transp ort / Migrant Workers & Stranded Travellers/ Media & Pr.rblicity/ Documentation. 1 1. A11 Deputy Commissioners, Mizoram. 12. A11 Superintendents of Police, Mworam. 13. Director, I&PR for wide publicity. -

TDC Syllabus Under CBCS for Persian, Urdu, Bodo, Mizo, Nepali and Hmar

Proposed Scheme for Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) in B.A. (Honours) Persian 1 B.A. (Hons.): Persian is not merely a language but the life line of inter-disciplinary studies in the present global scenario as it is a fast growing subject being studied and offered as a major subject in the higher ranking educational institutions at world level. In view of it the proposed course is developed with the aims to equip the students with the linguistic, language and literary skills for meeting the growing demand of this discipline and promoting skill based education. The proposed course will facilitate self-discovery in the students and ensure their enthusiastic and effective participation in responding to the needs and challenges of society. The course is prepared with the objectives to enable students in developing skills and competencies needed for meeting the challenges being faced by our present society and requisite essential demand of harmony amongst human society as well and for his/her self-growth effectively. Therefore, this syllabus which can be opted by other Persian Departments of all Universities where teaching of Persian is being imparted is compatible and prepared keeping in mind the changing nature of the society, demand of the language skills to be carried with in the form of competencies by the students to understand and respond to the same efficiently and effectively. Teaching Method: The proposed course is aimed to inculcate and equip the students with three major components of Persian Language and Literature and Persianate culture which include the Indo-Persianate culture, the vital portion of our secular heritage. -

Download PDF Here…

Vol. I No. 1 July-September, 2012 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor Prof. R.L.Thanmawia Joint Editor Dr. R.Thangvunga Assistant Editors Lalsangzuala K.Lalnunhlima Ruth Lalremruati PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 1 MIZO STUDIES July - September, 2012 Members of Experts English Section 1. Prof. Margaret Ch. Zama, Department of English. 2. Dr. R.Thangvunga, HOD, Department of Mizo 3. Dr. T. Lalrindiki Fanai, HOD, Department of English 4. Dr. Cherie L.Chhangte, Associate Professor, Department of English Mizo Section Literature & Language 1. Prof. R.L.Thanmawia, Padma Shri Awardee 2. Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte, Padma Shri Awardee 3. Dr. H.Lallungmuana, Ex.MP & Novelist 4. Dr. K.C.Vannghaka, Associate Professor, Govt. Aizawl College 5. Dr. Lalruanga, Former Chairman, Mizoram Public Service Commission. History & Culture 1. Prof. O. Rosanga, HOD, Dept. of History, MZU 2. Prof. J.V.Hluna, HOD, Dept. of History, PUC 3. Dr. Sangkima, Principal, Govt. Aizawl College. 3. Pu Lalthangfala Sailo, President, Mizo Academy of Letters & Padma Shri Awardee 4. Pu B.Lalthangliana, President, Mizo Writers’ Associa tion. 5. Mr. Lalzuia Colney, Padma Shri Awardee, Kanaan veng. 2 Mizo Studies July - Sept. 2012 CONTENTS 1. Editorial ... ... ... ... ... ... 5 English Section 2. R..Thangvunga Script Creation and the Problems with reference to the Mizo Language... ... ... ... 7 3. Lalrimawii Zadeng Psychological effect of social and economic changes in Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng ... ... 18 4. Vanlalchami Forces operating on the psyche of select character: A Psychoanalytic Study of Lalrammawia Ngente’s Rintei Zunleng. ... ... ... ... ... ... 29 5. K.C.Vannghaka A Critical Study of the Development of Mizo Novels: A thematic approach... -

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1

Mizo Studies April - June 2016 1 Vol. V No. 2 April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) Editor-in-Chief Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte PUBLISHED BY DEPARTMENT OF MIZO, MIZORAM UNIVERSITY, AIZAWL. 2 Mizo Studies April - June 2016 MIZO STUDIES Vol. V No. 2 (A Quarterly Refereed Journal) April - June, 2016 Editorial Board of Mizo Studies w.e.f April 2016.... Editor-in-Chief - Prof. Laltluangliana Khiangte Editor - Prof. R.Thangvunga Circulation Managers - Mr. Lalsangzuala - Mr. K. Lalnunhlima © Deptt. of Mizo, Mizoram University No part of any article published in this Journal may be reproduced in print or electronic form without the permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this Journal are the intellectual property of the contributors who are solely responsible for the effects they may have. The Editorial Board and publisher of the Journal will not entertain any legal responsibility. ISSN 2319-6041 _________________________________________________ Published by Prof Laltluangliana Khiangte, on behalf of the Department of Mizo, Mizoram University, Aizawl, and printed at the Gilzom Offset, Electric Veng, Aizawl. Mizo Studies April - June 2016 3 CONTENTS Editorial : Team Work - 5 English Section 1. Joseph C. Lalremruata Evolution of party Politics in Mizoram: A Study of the First Political Party - Mizo Union - 7 2. R. Thangvunga Magic and Witchcraft in Mizo Folklore - 17 3. Laltluangliana Khiangte Powerful Tones of Women in Mizo Folksongs - 23 Mizo Section 1. Darchuailova Renthlei Mizo |awng thl<k chhinchhiahna (Tone Markers)- 29 2. V. Lalberkhawpuimawia Thih hnu piah lam Pipute Suangtuahna Khawvel - 47 3. Denish Lalmalsawma Mizo Hlaa Poetic Technique kan hmuh \henkhatte- 71 4. -

Issues of Governor and Article 356 in Mizoram

Vol. VI, Issue 1 (June 2020) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Issues of Governor and Article 356 in Mizoram Lalrinngheta * Abstract In this article an attempt is made to study how the role of Governor is important in centre-state relations in India, pariticularly in the case of Mizoram. Its implications on the state especially when regime changes at the centre. Imposition of Article 356 thrice in the state of Mizoram and political background on which they were imposed were studied. Keywords : Governor, Article 356, Mizoram, Centre-State Relations. Mizoram was granted Union Territory only in 1972. From this time onwards till it attained statehood in 1987 there are six Lieutenant Governors in the U. T. After it attained statehood there are 18 Governors in the state till today (the incumbent one Kummanam Rajasekharan in 2018). These sixteen Governors of Mizoram were distinguished figures in their career and professions. Their professions vary from army personnel, politicians, bureaucrats, lawyers and agriculturist to academician.1 During the period 2014-2016 Mizoram had seven Governors. There has even been a feeling among the Mizo people that the Central Government was playing a dirty game with regard to the appointment of Governor in the state. The Mizo Zirlai Pawl (the largest student’s body in the state) also stated that the state deserved better treatment not just like where disfavoured Governors were posted. When BJP under the alliance of NDA formed government at the centre in 2014 turmoil had begun in the post of Governor of Mizoram. The first case being Vakkom B. Purushothaman. He was appointed as the 18 th Governor of Mizoram on 26 th August 2011 by President Pratibha Patil by replacing Madan Mohan Lakhera and took office on 2 nd September 2011 during Indian National Congress ruled at the centre.