Ross Andrew John 2016.Pdf (6.730Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

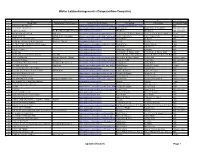

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

A University of Kwazulu-Natal Alumni Magazine

2020 UKZNTOUCH A UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL ALUMNI MAGAZINE NELSON R. MANDELA SCHOOL OF MEDICINE 70TH ANNIVERSARY INSPIRING GREATNESS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This edition of UKZNTOUCH celebrates the University of KwaZulu-Natal Nelson R. Mandela School of Medicine’s 70th Anniversary and its men and women who continue to contribute to the betterment of society, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Executive Editor: Normah Zondo Editorial Team: Bhekani Dlamini, Normah Zondo, Sinegugu Ndlovu, Finn Christensen, Deanne Collins, Sithembile Shabangu, Raylene Captain-Hasthibeer, Sunayna Bhagwandin, Desiree Govender and Nomcebo Msweli Contributors: Tony Carnie, Greg Dardagan, Colleen Dardagan, College PR Offices, Central Publications Unit, UKZNdabaOnline archives, UKZN academics, UKZN Press Creative Direction: Nhlakanipho Nxumalo Photographs and graphic illustrations: UKZN archives, UKZN Corporate Relations Division, UKZN photographers Copyright: All photographs and images used in this publication are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without permission of the UKZN Corporate Relations Division. No section of this publication may be reproduced without the written consent of the Corporate Relations Division. 2020 UKZNTOUCH A UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL ALUMNI MAGAZINE Disclaimer: Information was collected at different times during the compilation of this publication UKZNTOUCH 2020 CONTENTS 04 32 51 ANGELA HARTWIG 75 - COVID-19 HEROES FOREWORD UKZN ENACTUS IN THE ALUMNI CLASS NOTES EDITOR’S CHOICE TOP 16 AT ENACTUS WORLD -

Rev Dr Scott Couper

“A Sampling: Artefact, Document and Image” Rev Dr Scott Couper 18 March 2015 Forum for Schools and Archives AGM, 2015 The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Mission established Inanda Seminary in March 1869 as a secondary school for black girls. For a school to be established for black girls at this time was unheard of. It’s founding was radical, as radical as its first principal, Mary Kelly Edwards, the first single female to be sent by the American Board to southern Africa. Many of South Africa’s most prominent female leadership are products of the Seminary. Inanda Seminary produces pioneers: Nokutela Dube, co-founder of Ohlange Institute with her husband the Reverend John Dube, first President of the African National Congress (ANC), attended the Seminary in the early 1880s. Linguists and missionaries Lucy and Dalitha Seme, sisters of the ANC’s founder Pixley Isaka kaSeme, also attended the Seminary in the 1860s and 1870s. Anna Ntuli became the first qualified African nurse in the Transvaal in 1910 and married the first African barrister in southern Africa, Alfred Mangena. Nokukhanya Luthuli attended from 1917-1919 and taught in 1922 at the Seminary. Nokukhanya accompanied her husband, Albert Luthuli who was the ANC President-General and a member of the Seminary’s Advisory Board, to Norway to receive the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize in 1961. Edith Yengwa also schooled and taught at the Seminary; she attended from 1940, matriculated in 1946, began teaching in 1948 and became the school’s first black head teacher in 1966. The same year she left the Seminary for exile, joining her husband, Masabalala Yengwa, the Secretary of the Natal ANC. -

Annex F. RFQ #081419-01 Delivery Schedule Province District

Annex F. RFQ #081419-01 Delivery Schedule Learner Books Educator Guides Lot 1 Lot 3 Lot 2 Lot 1 Lot 3 Lot 2 No. of schools Province District Municipality Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Grade 9 Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade 7 Grade 8 Grade 9 Grade 10 Grade 11 Grade 12 Free State fs Thabo Mofutsanyane District Municipality > fs Maluti-a-Phofung Local Municipality 183 9,391 8,702 8,017 8,116 8,308 7,414 9,465 6,445 3,928 165 155 146 137 136 126 153 105 68 gp City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality > gp Johannesburg D (Johannesburg West) 128 10,124 9,918 9,322 8,692 7,302 6,879 8,848 6,698 4,813 162 158 150 104 58 55 137 108 79 Gauteng gp City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality > gp Johannesburg D (Johannesburg North) 63 3,739 3,736 3,519 3,196 3,361 3,344 3,879 3,037 2,433 64 65 62 54 37 35 47 39 33 gp City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality > gp Johannesburg D (Johannesburg Central) 148 7,378 6,675 6,388 6,329 7,737 7,234 8,557 6,504 4,979 138 119 113 113 117 113 134 104 82 kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality > kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Pinetown 1) 343 22,398 22,075 20,967 16,444 16,747 14,502 22,569 19,985 12,231 404 399 378 332 300 274 360 323 196 KwaZulu Natal kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality > kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Pinetown DREAMS) kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality > kz eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality (Umlazi) 175 4,640 4,032 4,033 3,290 6,393 5,667 9,406 8,039 5,854 87 80 82 77 109 103 155 133 102 kz King Cetshwayo District Municipality -

Billboard, Vol. XVII, No. 6, February 11, 1905

PRICE, 10 CENTS. FORTY PAGES. THEATRES^ CIROJSE MUSICIANS Weekly Volume XVII. No.fi. CINCINNATI NEW YORK CHICAGO February 11,1905. B. F. KEITH, The Well-Known Vaudeville Manager. Ttie Billboard been one of the greatest hits In the hlstor common sight Lu shooting galleries, and the of the London stage, and It Is still running. mechanical difficulties of making them support the weight of the girls was easily overcome by DRAMATIC The Barnum & Bailey twenty-four Hugh S. Thompson, who is securing a patent MINSTREL hour men have commenced work spending on the Idea. VAUDEVILLE BURLESQUE pleasant winter recuperating from the strena MUSIC cms campagn of 1904. Pete Conklln, as usual George Kdwardes' original London OPERA puts In his period of rest under his father' Company has made a very marked success In rooftree down In the wilds of Coney Islam: Henry Hamilton and Ivan Caryll's romantic while Harry Barnum spent tbe winter xm hi opera The Duchess of Dantzlc at Daly's Thea Island, to be built on the site of TUyou'i farm at Pottsvllle, Pa. tre. Ths piece, which is founded on the Steeplechase Park, announce that they have historic story of Mme. San Gene and Napoleon, m BROADWAY-GOSSIP. & a number of high-class spectacular acts which It Is rumored that W. W. Power has might perhaps be properly called a musk they are booking on the vaudeville circuits. purchased the troupe of trained ele- drama, dramatic interest dominating It mud. phants which were the feature of tbe Walte more strongly than any musical production ever During the recent storm Chas. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

53 West 28Th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley

DESIGNATION REPORT 53 West 28th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 516 Commission 53 West 28th Street LP-2629 December 10, 2019 DESIGNATION REPORT 53 West 28th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley LOCATION Borough of Manhattan 53 West 28th Street LANDMARK TYPE Individual SIGNIFICANCE Built c.1859 as an Italianate-style row house, 53 West 28th Street was the site of numerous musicians’ and sheet music publishers’ offices in the 1890s-1900s, part of a block known as “Tin Pan Alley.” Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 516 Commission 53 West 28th Street LP-2629 December 10, 2019 47, 49, 51, 53, and 55 West 28th Street, December 2019 LANDMARKS PRESERVATION COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS Lisa Kersavage, Executive Director Sarah Carroll, Chair Mark Silberman, General Counsel Frederick Bland, Vice Chair Timothy Frye, Director of Special Projects and Diana Chapin Strategic Planning Wellington Chen Kate Lemos McHale, Director of Research Michael Devonshire Cory Herrala, Director of Preservation Michael Goldblum John Gustafsson REPORT BY Anne Holford-Smith Sarah Moses, Research Department Everardo Jefferson Jeanne Lutfy Adi Shamir-Baron EDITED BY Kate Lemos McHale PHOTOGRAPHS BY Sarah Moses Landmarks Preservation Designation Report Designation List 516 Commission 53 West 28th Street LP-2629 December 10, 2019 3 of 48 Table of Contents 5 Testimony at the Public Hearing 6 Editorial Note 8 Summary 10 Building Description 11 History and Significance of Tin Pan Alley 11 Early Site History -

2018 Basic Education Support

2018 Basic Education Support Approved Applicants Updated: 01/10/2018 Kindly take note of the Reference number. The reference number will be assigned to the learner throughout their Education Support with DMV REF NUMBER DEPENDENT NAME DEPENDENT SURNAME SCHOOL NAME BE - CONT 1823 LESEGO AARON ST BONIFACE HIGH SCHOOL BE - CONT 3476 QENIEVIA HYGER ABRAHAMS BASTIAANSE SECONDARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 3660 RONIECHIA ABRAHAMS BASTIAANSE SECONDARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 0483 BONGINKOSI GYIMANI ADAM HECTOR PETERSON PRIMARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 2518 MOLEHE TSHEPANG ADAM KGAUHO SECONDARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 2881 NOLUBABALO NTOMBEKHAYA ADAM SEBETSA-O-THOLEMOPUISO HIGH SCHOOL BE - CONT 2925 NOMGCOBO NOLWANDLE ADAM ENHLANHLENI DAY CARE & PRE-SCHOOL BE - CONT 3955 SINETHEMBU NJABULO ADAM THULANI SECONDARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 0611 CASSANDRA NANNEKIE ADAMS LENZ PUBLIC SCHOOL BE - CONT 3743 SANDISO ADOONS SOUTHBOURNE PRIMARY SCHOOL BE - CONT 3746 SANELE ADOONS ROYAL ACADEMY BE - CONT 2393 MFUNDOKAZI AGONDO HOERSKOOL JAN DE KLERK BE - CONT 4440 THLALEFANG WILLINGTON AGONDO GRACE CHRISTIAN ACADEMY BE - CONT 0544 BRADLEY HARALD AHDONG CURRO ACADEMY PRETORIA BE - CONT 4900 ZAVIAN WHYSON AHDONG CURRO ACADEMY PRETORIA (MERIDIAN) BE - CONT 0546 BREANDAN GENE ALERS DR E.G JANSEN HOERSKOOL BE - CONT 1131 JUAN MATHEW ALEXANDER ZWAANSWYK HIGH SCHOOL BE - CONT 0045 AKEESHEA ALFESTUS RUSTHOF PRIMARY BE - CONT 0791 EMILIE JADE ALLEAUME RIDGE PARK COLLEGE BE - CONT 0387 BERTHA DILA ANDRE DANSA INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE BE - CONT 3915 SIMEONE ANDRE' GENERAL SMUTS HIGH SCHOOL BE - CONT 4234 TEBOHO -

The Family, Education, and Symbolic Struggles After Apartheid

Circuits of Schooling and the Production of Space: The family, education, and symbolic struggles after apartheid Mark Hunter Dept. of Human Geography University of Toronto, [email protected] WORK IN PROGRESS (comments very welcome but please do not cite without permission) Abstract Every weekday morning, in every South African city, scores of taxis, buses, and cars move children, black and white, long distances to attend schools. A simple explanation for the phenomenal rise of out-of-area schooling in South Africa—one perhaps unmatched anywhere in the world—is the end of apartheid’s racially divided schooling system in the 1990s. But focused on south and central Durban, this paper traces the emergence of ten distinct pathways that children take through different schools, referred to as “circuits of schooling.” The social- geographical inequalities that underpin schoolchildren’s movement today, it argues, are rooted in racial segregation under apartheid, rising inequalities within segregated areas from the 1970s, and a decisive shift from race- to class-based inequalities after 1994. However, rather than seeing children’s mobility as unfolding mechanically from social structure, life histories of parents and interviews with schoolteachers demonstrate that it is a) emerging from important gendered socio- spatial transformations in families/households; b) tied up with the reworking of symbolic power, including through the contested status of English language and schoolboy sports like rugby; c) and produced by (and producing) new struggles over space. As such, the paper proposes that the concurrent deracialization of schools, workplaces, and residential areas is marked by a new urban politics in which the “right to the city” and education are deeply intertwined. -

ILITHA HIA DESKTOP.Pdf

Page 1 of 19 A DESKTOP STUDY FOR THE PLACEMENT AND OPERATION OF THE AERIAL FIBRE OPTIC NETWORK IN KWAMASHU, INANDA, PHOENIX, AND NTUZUMA, ETHEKWINI MUNICIPALITY FOR ILITHA TELECOMMUNICATIONS (PTY) LTD DATE: 14 FEBRUARY 2021 By Gavin Anderson Umlando: Archaeological Surveys and Heritage Management PO Box 10153, Meerensee, 3901 Phone: 035-7531785 Cell: 0836585362 [email protected] ILITHA HIA DESKTOP Umlando 22/03/2021 Page 2 of 19 Abbreviations HP Historical Period IIA Indeterminate Iron Age LIA Late Iron Age EIA Early Iron Age ISA Indeterminate Stone Age ESA Early Stone Age MSA Middle Stone Age LSA Late Stone Age HIA Heritage Impact Assessment PIA Palaeontological Impact Assessment ILITHA HIA DESKTOP Umlando 22/03/2021 Page 3 of 19 INTRODUCTION Ilitha Telecommunications (Pty) Ltd (Ilitha), is finalising financing from the Development Bank of South Africa (DBSA) for the placement and operation of the aerial fibre optic network in KwaMashu, Inanda, Phoenix, and Ntuzuma, in the eThekwini Municipality. Aerial deployment of a fibre optic network offers significant cost reductions compared to traditional trenching methods. Design of the Ilitha aerial fibre network will closely resemble the existing electricity distribution network in most residential areas. This will enable pricing to be more affordable compared to traditional data providers. The footprint of the Ilitha fibre roll out will stretch across a 96.2 km2 area which covers communities in KwaMashu, Inanda, Phoenix, and Ntuzuma... The project area is situated approximately 12 kilometres north of Durban and is bordered by Reservoir Hills & Newlands East to the south, KwaDabeka & Molweni to the west, Mount Edgecombe & Blackburn Estate to the east and Mawothi & Trenance Park to the north. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Daddy Bob Troup Bob Troup Republic Music Corp

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Daddy Bob Troup Bob Troup Republic Music Corp. 1941 Daddy Has a Sweetheart, and Mother Is Her Name Dave Stamper Gene Buck G[ene] B[uck] Penn Music Co., Inc. 1912 Daddy Long Legs Harry Ruby Sam. M. Lewis FSM Waterson, Berlin & Snyder Co. 1919 Daddy You've Been a Mother to Me Fred Fisher Fred Fisher deTakas McCarthy & Fisher Inc. 1920 Band arrangement; have part for Daddy's Little Girl Francis A. Myers Myers Music House n.d. Oboe and Bassoon Daddy's Little Girl Bobby Burke Bobby Burke Manning Beacon Music Co. 1949 Daily Question, The (Du Fragst Mich Taglich), Op. 5 No. 5 Erik Meyer-Helmund Erik Meyer-Helmund De Luxe Music Co. n.d. Dainty Little Ingenue Gustav Luders Frank Pixley EM M. Witmark & Sons 1904 Dainty Reverie Alfred Fieldhouse W. A. Evans 1904 For piano Daisies Won't Tell (Waltz Song) Anita Owen Anita Owen Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1908 Daisies Won't Tell (Waltz Song) Anita Owen Anita Owen M. M. Cole Publishing Company 1940 Edward B. Marks Music Daisy Bell (A Bicycle Built For Two) Harry Dacre Harry Dacre Corporation 1933 Daisy Belle (Polka) B.A. Bloomey B. A. Bloomey n.d. Guitar accompaniment De Sylva, Brown and Henderson Dance Away the Night Dave Stamper Harlan Thompson Inc. 1929 Dance Espagnole (Spanish Dance), Op. 24 J. Ascher Century Music Publishing Co. 1920 Fingered by M. Greenwald Dance Me Loose Lee Erwin Mel Howard Erwin - Howard Music Co. 1951 Dance of the Bears Carl Heins Eclipse Publishing Co. -

John Scott, John Taylor, and Keats's Reputation John R

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1963 John Scott, John Taylor, and Keats's reputation John R. Gustavson Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Gustavson, John R., "John Scott, John Taylor, and Keats's reputation" (1963). Theses and Dissertations. 3152. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/3152 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .•••·· -·"' -· '1/- .~ •. -. ..... '·--·-· -- .. - ' . .. ·~ ... - ... ·-··--·--- ·-·--·-··-~•-•¥••----., ...... .. ' ·:.0.--:'_• _ _.., ___•1-' .......""T,b.-~-~~f'Mt,'lllr!iill. 1"• ... ,~'"!".~·· -- . ~..... .... ,Ill\ ,, •• ,":• -r---1 'I • - .. , .•. - ... -----fQS' ·--·~· ....... 1:·.·" ...... ~ , • ' ..,.: .tf>•Z • .... -..... ' ........ -.--···· ... _ .. _ ' i .I JOHN SCOTT,.. JOHN TAYLOR, AND KEATS'S REPUTATION - by John Raymond Gustavson A THESIS Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Lehigh University in candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts 1, ·• Lehigh University ··,~-- 1963 -•• · l• -- ·.:·_ .;·~: ..:,.:... _. - -- - --· -- ·---..: --;---:•--=---· -, ~ _., --.~ .... •.-' ... ------- ,.1 ... !" ·.,i .1 l,! ; ': ·)1 :i - ' -~·-· ~ _ _.,.,::_ '. -• .:,•,,", .,_ '' - . ' ... -.. ~.:-_•;,." -, ii ... • '~,:~ ...... ··rt· • -···-•-Y: .. --~--,-•,:·,·,:-~:.• .~,' .,~