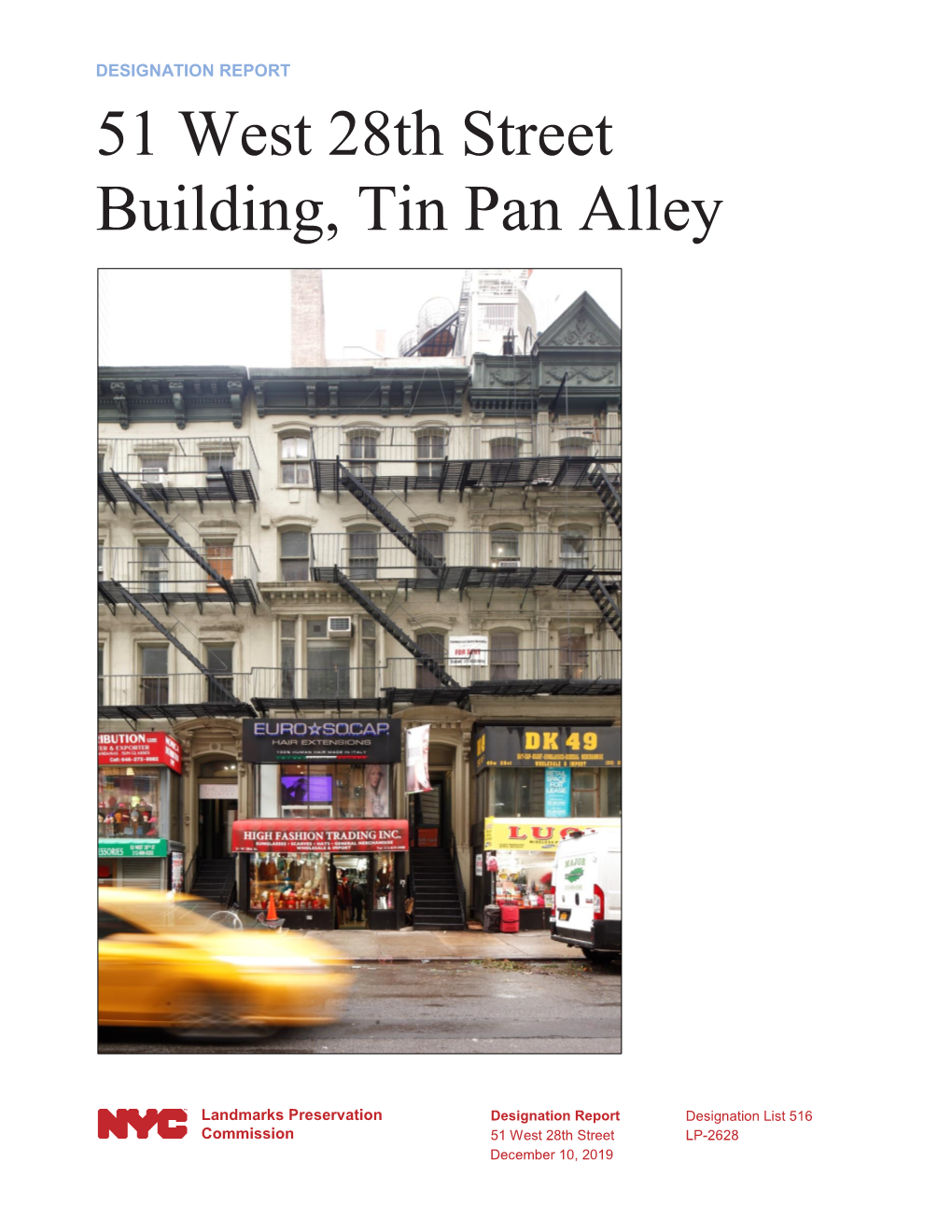

51 West 28Th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoosier Hard Times - Life Was a Strange, Colorful Kaleidoscopic Welter Then

one Hoosier Hard Times - Life was a strange, colorful kaleidoscopic welter then. It has remained so ever since. A HOOSIER HOLIDAY since her marriage in 1851, Sarah Schänäb Dreiser had given birth al- most every seventeen or eighteen months. Twelve years younger than her husband, this woman of Moravian-German stock had eloped with John Paul Dreiser at the age of seventeen. If the primordial urge to reproduce weren’t enough to keep her regularly enceinte, religious forces were. For Theodore Dreiser’s father, a German immigrant from a walled city near the French border more than ninety percent Catholic, was committed to prop- agating a faith his famous son would grow up to despise. Sarah’s parents were Mennonite farmers near Dayton, Ohio, their Czechoslovakian ances- tors having migrated west through the Dunkard communities of German- town, Bethlehem, and Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Sarah’s father disowned his daughter for marrying a Catholic and converting to his faith. At 8:30 in the morning of August 27, 1871, Hermann Theodor Dreiser became her twelfth child. He began in a haze of superstition and summer fog in Terre Haute, Indiana, a soot-darkened industrial town on the banks of the Wabash about seventy-five miles southwest of Indianapolis. His mother, however, seems to have been a somewhat ambivalent par- ent even from the start. After bearing her first three children in as many years, Sarah apparently began to shrink from her maternal responsibilities, as such quick and repeated motherhood sapped her youth. Her restlessness drove her to wish herself single again. -

Bangor Publishing Company

Blue Hill's 'Forum' fulfills longing for summertime laughs Thursday, July 17, 2008 - Bangor Daily News Summer, especially summer in Maine, is for laughter. In offering up "A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum," the New Surry Theatre not only recognizes but also honors this notion in its production that opened Friday and runs weekends through Aug. 16. The company’s production at the Blue Hill Town Hall Theater of the 1962 musical that earned Stephen Sondheim the first of many Tony Awards is a delicious way to spend a summer evening. The local talent serves up a show that’s a step above the usual community theater fare thanks to the tight direction of Bill Raiten and marvelous mugging of lead actor Michael Reichgott. "Forum" is loosely based on three comedies by the Roman playwright Plautus and tells the story of the Herculean efforts by the slave Pseudolus to earn his freedom from Hero, his young master. The only things standing in his way are courtesans, soldiers, long-lost children, a virgin and a fellow slave. Reichgott, who is a newcomer to Maine and the theater company, seems to channel Zero Mostel and Nathan Lane, who played the role on Broadway in 1962 and 1996, respectively. He hams it up colossally, always stepping up to but never crossing that thin line that divides hysterically funny from grossly crass. The actor is equally adept at the physical comedy, the double-entendres and belting the role requires. Reichgott wrings every drop of humor from the part and throwing himself into his character’s big numbers — "Comedy Tonight," "Free" and "Everybody Ought to Have a Maid." He is nearly matched by Christopher Candage as Hero and Jim Fisher as Hysterium, his fellow slave. -

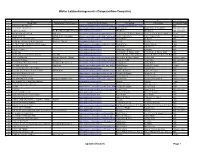

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

TRU Speak Program 021821 XS

THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED VIRTUAL BENEFIT PLAYBILL TRU SPEAK Hear Our Voices! An evening of awareness to benefit THEATER RESOURCES UNLIMITED executive producer Bob Ost associate producers Iben Cenholt and Joe Nelms benefit chair Sanford Silverberg plays produced by Jonathan Hogue, Stephanie Pope Lofgren, James Rocco, Claudia Zahn assistant to the producers Maureen Condon technical coordinator Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms editor-technologists Iben Cenholt/RuneFilms, Andrea Lynn Green, Carley Santori, Henry Garrou/Whitetree, LLC video editors Sam Berland/Play It Again Sam’s Video Productions, Joe Nelms art direction & graphics Gary Hughes casting by Jamibeth Margolis Casting Social Media Coordinator Jeslie Pineda featuring MAGGIE BAIRD • BRENDAN BRADLEY • BRENDA BRAXTON JIM BROCHU • NICK CEARLEY • ROBERT CUCCIOLI • ANDREA LYNN GREEN ANN HARADA • DICKIE HEARTS • CADY HUFFMAN • CRYSTAL KELLOGG WILL MADER • LAUREN MOLINA • JANA ROBBINS • REGINA TAYLOR CRYSTAL TIGNEY • TATIANA WECHSLER with Robert Batiste, Jianzi Colon-Soto, Gha'il Rhodes Benjamin, Adante Carter, Tyrone Hall, Shariff Sinclair, Taiya, and Stephanie Pope Lofgren as the Voice of TRU special appearances by JERRY MITCHELL • BAAYORK LEE • JAMES MORGAN • JILL PAICE TONYA PINKINS •DOMINIQUE SHARPTON • RON SIMONS HALEY SWINDAL • CHERYL WIESENFELD TRUSpeak VIP After Party hosted by Write Act Repertory TRUSpeak VIP After Party production and tech John Lant, Tamra Pica, Iben Cenholt, Jennifer Stewart, Emily Pierce Virtual Happy Hour an online musical by Richard Castle & Matthew Levine directed -

The Last Days of Buster Keaton John C. Tibbetts

Fall 1995 79 The Hole in the Doughnut: The Last Days of Buster Keaton John C. Tibbetts In the Fall of 1995 Eleanor Norris Keaton will come to Kansas to celebrate the 100th birthday of her late husband.1 Part of an extensive itinerary that also takes her to other centenary observances in New York, Muskegon, Michigan, and Los Angeles, the Kansas trip is particularly poignant. Keaton was born on October 4,1895, in the tiny farm community of Piqua, in southeast Kansas, while his parents were performing with a medicine show.2 Although he may have been a Kansan only through sheer accident of circumstances—the baby and his mother remained in Piqua only two weeks before rejoining the troupe on the road—he returned there many times as a child on tour with his parents.3 Later, the classic slapstick comedian paid tribute to his home state in many of the themes and situations of his best films, most notably in the cyclone sequence in Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928). To my mind, even his trademark "deadly horizontal" hat (as James Agee described it) evokes the stark flatness of the Kansas prairies.4 While the Keaton phenomenon will be fully explored throughout the centenary year, Eleanor herself should not be forgotten. By all accounts, she was an important force in Buster's later years. "She has seen Buster Keaton through a long period of painful adjustment, relapse, and readjustment and a dozen partial comebacks," wrote Rudi Blesh, shortly before Buster's death on February 1,1966. "She has carried him, content and at times happy, across the threshold of his seventies. -

Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 6-19-1973 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1973). Winona Daily News. 1303. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/1303 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cloudy t!i rough ' ' ¦ "V- :- - '_ jft^- ' .r- .- '- -OErs6Mi :, y'l- • .:¦ ¦' Wednesday witfiy :¦-¦ Bioytop.Btirs,.. : ¦ ' ¦ ¦ -' - -/K ^'J . " ¦ "#Sr\Reail the¦ Want¦ ¦ ¦Ads¦ v¦ ¦y- .y.vychahcit bf showers ,afie5.rtK . : I- - - ---- " J . - . 118th Year of Pobrieailori 4 Seetfoni, 34 Pagjflsi 15 Cin*« Friendly afrndspfe Stimitiit By GAYLORD SHAW talks- reporters at the party, " . turnam certain that I'm that I Congressto looms as trade a potential stumbling block: ¦:- ;. WASHINGTON .AP). -; After- .agreeing V. 'there. going to leave here ( the United States) ^iri a. very, to increased U.S.-Soviet trade;: The 'Soviets . -''interest ' - .; ' - " Isf: no, alternative fto. a p«licy of peace,". President - •good mood."' . -f "P": in overcoming legislative opposition wasf . evident in Nixon and Soviet leader Leonid I. Brezhnev turned He described the first round of talkf fas = "very Brezhnev's Invitation to members of the Stenate For- ' their . summit; talks today : to the • ..thorn;/¦ issues of friendly. I' was • -very.'ji appy ," . 'A; eign Relations Corrirriittee to have itinch with him ai ?" "¦¦ "*" - " trade; and economics. W . -

Historical Resource Evaluation

ATTACHMENT 2 LPC 11-05-15 Page 1 of 44 HISTORICAL RESOURCE EVALUATION 2556 TELEGRAPH AVENUE BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA TIM KELLEY CONSULTING, LLC HISTORICAL RESOURCES 2912 DIAMOND STREET #330 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94131 415.337-5824 [email protected] ATTACHMENT 2 LPC 11-05-15 HISTORICAL RESOURCE EVALUATION 2556 TELEGRAPH AVENUE BERKELEY, CALIFORNIAPage 2 of 44 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tim Kelley Consulting (TKC) was engaged to conduct an Historical Resource Evaluation (HRE) for 2556 Telegraph Avenue, a steel frame brick faced commercial building constructed circa 1946, with a 1962 addition, in Berkeley’s LeConte neighborhood. TKC conducted a field survey, background research of public records, and a literature and map review to evaluate the subject property according to the significance criteria for the California Register of Historical Resources (CRHR) and the City of Berkeley’s Landmarks Preservation Ordinance. Subsequent sections of this report present the detailed results of TKC’s research. Based on that research, TKC concludes that 2556 Telegraph is not eligible for listing in the California Register of Historical Resources, nor does it appear eligible for listing as a City Landmark, Structure of Merit, or contributor to an identified historic district. Accordingly, 2556 Telegraph does not appear to be a historical resource for the purposes of the California Environmental Quality Act. REV 2. MARCH 2015 TIM KELLEY CONSULTING -1- ATTACHMENT 2 LPC 11-05-15 HISTORICAL RESOURCE EVALUATION 2556 TELEGRAPH AVENUE BERKELEY, CALIFORNIAPage 3 of 44 II. METHODS A records search, literature review, archival research, consultation, field survey, and eligibility evaluation were conducted for this study. Each task is described below. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Berkeley Architectural Heritage Society Oral History Project ELLA

Berkeley Architectural Heritage Society Oral History Project ELLA (BARROWS) HAGAR 'Mediterranean~Stvle'in'fheeBerkelev Hills 245 Stonewall Road Berkeley, California 94705 Architect: WILLIAEi IURSTER Completed in 1928 in Holabird Garber Park and other subdivisions JOHN GARBER ESTATE Kellersberger's Plot No. 77 Interviewer Rosemary Levenson 261 Stonewall Road Berkeley, CA 94705 Regional Oral History Office Berkeley Architectural The Bancroft Library Heritage Society University of California P.O. Box 7066 Berkeley, California 94720 Landscape Station Berkeley, California 94707 TABLE OF CONTENTS--Ella (Barrows) Hagar Mediterranean Style in the Berkeley Hills FRONTISPIECE INTERVIEW HISTORY i AGENDA iii SAMPLE CONTRACT iv BERKELEY ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE ASSOCIATION QUESTIONNAIRE v Choosing a Lot Architects and Architectural Styles Early Houses on Upper Stonewall Road Berkeley Address and Oakland Taxes The Garber Family John Garber Park and the City of Berkeley Quarry Cars and Steep Streets The Stonewall Community Annual Christmas Pageant A Closed Right of Way and Old Fish Ranch Road The John Roosevelts on Stonewall Road Levensons Move Next Door INDEX INTERVIEW HISTORY Ella Hagar's recollections of the development of the upper part of Stone- wall Road were recorded as a pilot oral history project for the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association. The impetus was the interviewer's curiosity about the history of her own neighborhood. B.A.H.A.'s encouragement led to the completion of the project. We hope that others will also be encouraged to record the reminiscences of their knowledgeable neighbors and friends and thus preserve memories of the early history of Berkeley's buildings and neighborhoods that would otherwise be lost. -

A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930

Closer Connections: A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences by Debra K. Burgess B.A. University of Cincinnati June 2012 M.A. University of Cincinnati April 2014 Committee Chair: Mark A. Raider, Ph.D. 24:11 Abstract Closer Connections: A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930 by Debra K. Burgess Child welfare programs in the United States have their foundation in the religious traditions brought to the country up through the late nineteenth century by immigrants from many European nations. These programs were sometimes managed within the auspices of organized religious institutions but were also found among the ad hoc efforts of religiously- motivated individuals. This study analyzes how the religious traditions of Catholicism, Judaism, and Protestantism established and maintained institutions of all sizes along the lines of faith- based dogma and their relationship to American cultural influences in the Midwest cities of Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh during the period of 1880-1930. These influences included: the close ties between (or constructive indifference exhibited by) the secular and sectarian stakeholders involved in child-welfare efforts, the daily needs of children of immigrants orphaned by parental disease, death, or desertion, and the rising influence of social welfare professionals and proponents of the foster care system. -

Film Locations in San Francisco

Film Locations in San Francisco Title Release Year Locations A Jitney Elopement 1915 20th and Folsom Streets A Jitney Elopement 1915 Golden Gate Park Greed 1924 Cliff House (1090 Point Lobos Avenue) Greed 1924 Bush and Sutter Streets Greed 1924 Hayes Street at Laguna The Jazz Singer 1927 Coffee Dan's (O'Farrell Street at Powell) Barbary Coast 1935 After the Thin Man 1936 Coit Tower San Francisco 1936 The Barbary Coast San Francisco 1936 City Hall Page 1 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Fun Facts Production Company The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company During San Francisco's Gold Rush era, the The Essanay Film Manufacturing Company Park was part of an area designated as the "Great Sand Waste". In 1887, the Cliff House was severely Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) damaged when the schooner Parallel, abandoned and loaded with dynamite, ran aground on the rocks below. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Warner Bros. Pictures The Samuel Goldwyn Company The Tower was funded by a gift bequeathed Metro-Goldwyn Mayer by Lillie Hitchcock Coit, a socialite who reportedly liked to chase fires. Though the tower resembles a firehose nozzle, it was not designed this way. The Barbary Coast was a red-light district Metro-Goldwyn Mayer that was largely destroyed in the 1906 earthquake. Though some of the establishments were rebuilt after the earthquake, an anti-vice campaign put the establishments out of business. The dome of SF's City Hall is almost a foot Metro-Goldwyn Mayer Page 2 of 588 10/02/2021 Film Locations in San Francisco Distributor Director Writer General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin General Film Company Charles Chaplin Charles Chaplin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) Eric von Stroheim Eric von Stroheim Warner Bros. -

Hole in the 'Hood

no. 76 PUBLISHED CENTRAL CITY BY THE Thawing SAN FRANCISCO STUDY CENTER MARCH cold cases 2008 Several slayings on SFPD hot list P.O., are in District 6 WE WON’T BY T OM C ARTER GO HE murder of a 9-year girl in SAN FRANCISCO her Tenderloin apartment Residents Tbuilding is among several cold cases in District 6 that homicide protest for full Inspector Joseph Toomey and his partner are investigating, Toomey post office O RIGINAL J OE’ S told those assembled at the Tender - loin police captain’s meeting Feb. 26. PAGE 2 The crime occurred nearly 24 year ago in the five-story apartment building at 765 O’Farrell St. DNA is expected to play a major role, if the special investigative unit created a year ago is to solve the case. On April 10, 1984, Mei Leung and her 8-year-old brother, Mike, were returning home. As they got close to the building’s steps Mei dropped a dollar bill. Police believe the bill blew under a door to the basement or somewhere inside the building. Mei told her brother she was going into the basement and would look for the bill near the elevator. Mike took the ele- PLUSH “People don’t vator upstairs alone and went inside MYSTERY realize what the family’s apart- ment but didn’t say SOLVED impact a anything to his murder has mother. It was nearly 15 minutes Stuffed P HOTOS BY L ENNY L IMJOCO on a family.” before she noticed Frank, owner and night bartender at the 21 Club near Original Joe’s, sorely misses the restaurant Mei was not around.