Hoosier Hard Times - Life Was a Strange, Colorful Kaleidoscopic Welter Then

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keys MHS Girls in Humanitarian Circumstan by ALEXGIRELLI Managers, to Improve Delivery of Ces

MONDAY LOCAL NEWS INSIDE iianrhpHtpr ■Nike house purchase before board. ■Special Focus program off to good start. ■SNET moves more to Coventry exchange. What’s ■ Route 6 plan to be presented shortly. News Local/Regional Section, Page 7. Sept. 10,1990 Gulf at a glance (AP) Here, at a glance, are the Vbur Hometown Newspaper Voted 1990 New England Newspaper of the Year Newsstand Price: 35 Cents latest developments in the Per sian Gulf crisis: ■ President Bush said die iHanrliPstrr HrralJi Red Sox triumph Helsinki summit with Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev resulted m a “loud and clear” condemnation of Iraq’s Saddam over Mariners Morrison set on Hussein. Bush played down Gorbachev s reluctance to go — along with the U.S. threat of see page 45 force if sanctions fail to force SPORTS Iraq to wiUidraw from Kuwait reorganizing and unwillingness to remove the remaining 150 Soviet military advisers from Iraq. government ■ Food shipments to Iraq and occupied Kuwait will be allowed keys MHS girls in humanitarian circumstan By ALEXGIRELLI managers, to improve delivery of ces. Bush and Gorbachev Manchester Herald services. agreed. They said the United He said the objectives of state Nations, whose Security Council Indians looking MANCHESTER —Bruce Mor voted Aug. 6 to embargo all Please see MORRISON, page 6. rison, the convention-endorsed trade with Iraq because it had in o Democratic candidate for governor, vaded Kuwait four days earlier, 33 TI to advance further says the state needs to reorder its would define the special cir 2 F priorities and he says he is the best Herald support cumstances. -

Sault Tribe Receives $2.5M Federal HHS Grant Tribe Gets $1.63 Million

In this issue Recovery Walk, Pages 14-15 Tapawingo Farms, Page 10 Squires 50th Reunion, Page 17 Ashmun Creek, Page 23 Bnakwe Giizis • Falling Leaves Moon October 7 • Vol. 32 No. 10 Win AwenenOfficial newspaper of the SaultNisitotung Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Sault Tribe receives $2.5M federal HHS grant The Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of diseases such as diabetes, heart tobacco-free living, active living blood pressure and high choles- visit www.healthysaulttribe.net. Chippewa Indians is one of 61 disease, stroke and cancer. This and healthy eating and evidence- terol. Those wanting to learn more communities selected to receive funding is available under the based quality clinical and other To learn more about Sault Ste. about Community Transformation funding in order to address tobac- Affordable Care Act to improve preventive services, specifically Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians’ Grants, visit www.cdc.gov/com- co free living, active and healthy health in states and communities prevention and control of high prevention and wellness projects, munitytransformation. living, and increased use of high and control health care spending. impact quality clinical preventa- Over 20 percent of grant funds tive services across the tribe’s will be directed to rural and fron- seven-county service area. The tier areas. The grants are expected U.S. Department of Health and to run for five years, with projects Human Services announced the expanding their scope and reach grants Sept. 27. over time as resources permit. The tribe’s Community Health According to Hillman, the Sault Department will receive $2.5 mil- Tribe’s grant project will include lion or $500,000 annually for five working with partner communities years. -

Names in Marilynne Robinson's <I>Gilead</I> and <I>Home</I>

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 139–49 Names in Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Home Susan Petit Emeritus, College of San Mateo, California, USA The titles of Marilynne Robinson’s complementary novels Gilead (2004) and Home (2008) and the names of their characters are rich in allusions, many of them to the Bible and American history, making this tale of two Iowa families in 1956 into an exploration of American religion with particular reference to Christianity and civil rights. The books’ titles suggest healing and comfort but also loss and defeat. Who does the naming, what the name is, and how the person who is named accepts or rejects the name reveal the sometimes difficult relationships among these characters. The names also reinforce the books’ endorsement of a humanistic Christianity and a recommitment to racial equality. keywords Bible, American history, slavery, civil rights, American literature Names are an important source of meaning in Marilynne Robinson’s prize-winning novels Gilead (2004) and Home (2008),1 which concern the lives of two families in the fictional town of Gilead, Iowa,2 in the summer of 1956. Gilead is narrated by the Reverend John Ames, at least the third Congregationalist minister of that name in his family, in the form of a letter he hopes his small son will read after he grows up, while in Home events are recounted in free indirect discourse through the eyes of Glory Boughton, the youngest child of Ames’ lifelong friend, Robert Boughton, a retired Presbyterian minister. Both Ames, who turns seventy-seven3 that summer (2004: 233), and Glory, who is thirty-eight, also reflect on the past and its influence on the present. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930

Closer Connections: A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences by Debra K. Burgess B.A. University of Cincinnati June 2012 M.A. University of Cincinnati April 2014 Committee Chair: Mark A. Raider, Ph.D. 24:11 Abstract Closer Connections: A Regional Study of Secular and Sectarian Orphanages and Their Response to Progressive Era Child-Saving Reforms, 1880-1930 by Debra K. Burgess Child welfare programs in the United States have their foundation in the religious traditions brought to the country up through the late nineteenth century by immigrants from many European nations. These programs were sometimes managed within the auspices of organized religious institutions but were also found among the ad hoc efforts of religiously- motivated individuals. This study analyzes how the religious traditions of Catholicism, Judaism, and Protestantism established and maintained institutions of all sizes along the lines of faith- based dogma and their relationship to American cultural influences in the Midwest cities of Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh during the period of 1880-1930. These influences included: the close ties between (or constructive indifference exhibited by) the secular and sectarian stakeholders involved in child-welfare efforts, the daily needs of children of immigrants orphaned by parental disease, death, or desertion, and the rising influence of social welfare professionals and proponents of the foster care system. -

84.1966.1 Birthplace of Paul Dresser (1859-1906) 84.1966.3 Birthplace of Paul Dresser (1859) Vigo County Marker Text Review Report 3/21/2013

84.1966.1 Birthplace of Paul Dresser (1859-1906) 84.1966.3 Birthplace of Paul Dresser (1859) Vigo County Marker Text Review Report 3/21/2013 Marker Texts Composer of Indiana State Song, “On the Banks of the Wabash,” and other songs popular in the Gay Nineties. His famous brother, Theodore Dreiser, wrote An American Tragedy and other novels. Composer of Indiana State Song, “On the Banks of the Wabash,” “My Gal Sal,” and many more, popular in the gay 90’s era. His famous brother, author Theodore Dreiser, wrote An American Tragedy and other novels. Report The markers commemorating Paul Dresser (born Dreiser) have been reviewed because their files contained inadequate primary sources to verify the marker texts. This report also provides additional information about Dresser and the significance of his song “On the Banks of the Wabash.” Both markers report Dresser’s birth date in 1859, but sources disagree and claim that he was born in 1857, 1858, or 1859.1 The U.S. Federal Census for the years 1860, 1870, and 1880 all list his birth year as “about 1858.” Both the 1860 and 1880 census records place him in Terre Haute, Indiana, but newspapers disagree on the exact location of his birth.2 A pamphlet issued by the Vigo County Historical Society states that the house he reportedly grew up in was moved to Fairbanks Park on Dresser Dr. in Terre Haute in the 1960s, where it still stands today.3 The rest of the text is accurate for both markers, but each omits quite a bit of detail regarding Dresser’s life. -

Elliott Roosevelt: a Paradoxical Personality in an Age of Extremes Theodore M

Elliott Roosevelt: A Paradoxical Personality in an Age of Extremes Theodore M. Billett Elliott Roosevelt, the enigmatic younger brother of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, is a compelling study in contradiction. Though several of Elliott’s closest family members—from his brother to his daughter, Eleanor—became important figures on the national stage in twentieth century America, he has largely been forgotten. The reasons historians overlook Elliott, including his obscurity and the calamitousness of his lifetime, are not unlike the motives that drove his family to similar reticence. Yet, a deeper and more nuanced treatment of Elliott reveals much about late nineteenth century America and about a complicated personality with intrinsic connections to important historical actors. Like the Civil War of his childhood and the Gilded Age in which he lived, Elliott’s life presents a complicated, often paradoxical existence. Born to a family dissevered by the Civil War, raised in aristocratic society but financially inept, devoted to social welfare causes but engaged in a life of frivolity and ostentation, praised for his likeability but disdained for his selfishness, raised on notions of temperance and morality but remembered for his intractable drinking and debauchery, Elliott resists simplistic, unifying definitions. Unable to tease apart the bifurcated nature of Elliott’s life, a more effective picture of his character can be presented by wading into the mire of his contrasts. Significant representations of Elliott’s duplicitous reality and his conflicting conduct can be seen throughout his life. His household and family were wrenched by the Civil War. He was committed to helping the unfortunate and needy, but lived the life of Gilded Age boulevardier. -

IBC Bioethics & Film Special Topic: Workshop/Interactive Session

IBC Bioethics & Film Special Topic: Workshop/Interactive Session: Teaching with Bioethics Documentaries & Films Thursday, June 9, 2016; 5:30-6:30 pm Laura Bishop, Ph.D. I. Introductory Remarks II. Bioethics & Film: Why, Practical Details, and Resources A. Why? Using video / film in the classroom or committee setting (handout) B. Practical Details 1. Preparation Time (editing and laying the groundwork) 2. Post-Viewing Time/Debriefing (ensuring viewers took home the right message; correcting false information) 3. Real Issues / Cases (documentary, non-fiction, fiction/entertainment; real cases get you more mileage) 4. Sensitivity (visual presentation may be overwhelming for some) 5. Mix Serious / Humorous – short clip – Cutting Edge: Genetic Repairman Sequence 6. Variety of Types 7. Range of Lengths 8. Copyright / Permissions Issues / Educational Licensing (trailers used) C. Resources 1. List of some sources to identify, watch, purchase bioethics-related videos/films (handout) 2. List of commercial films with bioethics themes (online) III. Workshop Piece / Interactive (Tools for Using Films) (see multi-page activity handout) Ø Who Decides: Ethics for Dental Practitioners (individual analysis to group discussion) Ø Me Before You and The Intouchables (compare, contrast, similarities) Ø Beautiful Sin (argument analysis: arguments pro & con; rules vs. outcomes) Ø Perfect Strangers (pretest/posttest; know, learn, need to know; double entry journal; discussion Q.) (http://www.perfectstrangersmovie.com; www.jankrawitz.com) Ø Just Keep Breathing: Moral Distress in the PICU (Pediatric Intensive Care Unit) (standing in the shoes - role play; ethics committee) (http://www.justkeepbreathingfilm.com) Case One Case Two IV. IBC42 Group Idea Sharing V. Resources: Jeanne Ting Chowning, MS, and Paula Fraser, MLS. -

"The Revolutionist" Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE This guide is an invitation to dialogue. To listen and explore. Above all, to celebrate the spirit of our democracy and those who continue the hard work of bringing our country’s ideals to life. A Film by WFYI Public Media Discussion Guide produced by WFYIC The Revolutionist is made possible through the generous support of The William Craig and Teneen Dobbs Charitable Foundation, Amalgamated Bank, Amalgamated Life Insurance Company, SMART – International Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers, Local Union No. 20, Ullico, Incorporated, the Michael and Amy Sullivan Family Foundation and other generous donations. The documentary is intended for private, non-commercial purposes. © 2019 Metropolitan Indianapolis Public Media DISCUSSION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE FILM AND CONVERSATION ....................................... Film Synopsis ....................................................................... The Production Team ................................................................. Our Hope for Your Discussion .......................................................... FACILITATOR TIPS and GUIDANCE........................................................ Facilitating a Film-based Conversation.................................................... Balancing Time and Good Questions .................................................... Managing the Quality and Tenor of Any Group Conversation ................................ Facilitating a Conversation About The Revolutionist in Politically-Charged -

EMAIL Community Welcome Packet

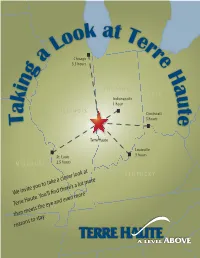

k at T oo er L r a Chicago e 3.5 hours g H n a i INDIANA OHIO u Indianapolis k 1 hour t a ILLINOIS Cincinnati e 3 hours T Terre Haute Louisville St. Louis 3 hours MISSOURI 2.5 hours KENTUCKY We invite you to take a closer look at Terre Haute. You’ll nd there’s a lot more than meets the eye and even more reasons to stay. Welcome Dear Friend, On behalf of the over 790 members of the Terre Haute Chamber of Commerce, we are pleased to provide you with information about Terre Haute. As the heart of the Wabash Valley, Terre Haute serves over a quarter-of-a-million residents throughout 16 counties as a major regional shopping, healthcare, manufacturing, and service hub in West Central Indiana. Terre Haute is a modern Midwest city with a proud heritage. Located along the beautiful Wabash River in Vigo County, Indiana, we are a progressive and vibrant community with a bright vision for the future. We are also home to a wide array of small, medium and Fortune 500 industries, four colleges, a state university, state-of-the-art public schools, wonderful parks, great shopping, a variety of restaurants and an experienced and educated workforce. Throughout this booklet, you will nd a variety of information, providing valuable details on many aspects of our community, including education, industry and recreation. If you feel this information does not adequately answer your questions about our ne city, please feel free to contact us and we will be happy to provide additional details. -

Chapter Outline

CHAPTER TWO: “AFTER THE BALL”: POPULAR MUSIC OF THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES Chapter Outline I. Minstrelsy A. The minstrel show 1. The first form of musical and theatrical entertainment to be regarded by European audiences as distinctively American in character 2. Featured mainly white performers who artificially blackened their skin and carried out parodies of African American music, dance, dress, and dialect 3. Emerged from rough-and-tumble, predominantly working-class neighborhoods such as New York City’s Seventh Ward, commercial urban zones where interracial interaction was common 4. Early blackface performers were the first expression of a distinctively American popular culture. B. George Washington Dixon 1. The first white performer to establish a wide reputation as a “blackface” entertainer 2. Made his New York debut in 1828 3. His act featured two of the earliest “Ethiopian” songs, “Long Tail Blue” and “Coal Black Rose.” CHAPTER TWO: “AFTER THE BALL”: POPULAR MUSIC OF THE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES a) Simple melodies from European tradition C. Thomas Dartmouth Rice (1808–60) 1. White actor born into a poor family in New York’s Seventh Ward 2. Demonstrated the potential popularity and profitability of minstrelsy with the song “Jim Crow” (1829), which became the first international American song hit 3. Sang this song in blackface while imitating a dance step called the “cakewalk,” an Africanized version of the European quadrille (a kind of square dance) 4. The cakewalk was developed by slaves as a parody of the “refined” dance movements of the white slave owners. a) The rhythms of the music used to accompany the cakewalk exemplify the principle of syncopation. -

Wabash River Heritage Corridor Management Plan 2004

Wabash River Heritage Corridor Management Plan 2004 Wabash River Heritage Corridor Commission 102 North Third Street, Suite 302 Lafayette, IN 47901 www.in.gov/wrhcc www.in.gov/wrhcc 1 WABASH RIVER HERITAGE CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN - TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………… 2 Executive Summary …………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction …………………………………………………………………… 5 Wabash River Heritage Corridor Fund …………………………………… 6 Past Planning Process ………………………………………………….... 7 The Vision and Need for a Revised Corridor Management Plan …………… 8 VALUES ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Land Use and Population – Resource Description …………………………… 10 Land Use - Implementation Strategies and Responsibilities …………………… 12 Case Study – Land Use Planning Approach in Elkhart County…………………… 13 Natural Resources – Resource Description …………………………… 15 Natural Resource Implementation Strategies and Responsibilities ……………….. 19 and Best Management Practices Historical/Cultural Overview and Resources …………………………… 23 Historic Resources Implementation Strategies and Responsibilities …………… 27 Historic Preservation Successes in the Wabash River Heritage Corridor ………… 28 Recreation Overview and Resources …………………………………… 30 Recreation Implementation Strategies and Responsibilities …………………… 31 Corridor Connections and Linkages …………………………………… 33 Corridor Trail Linkages – Overview and Resources …………………… 33 Trail Implementation Strategies and Responsibilities …………………………… 33 River/Watertrail Linkages - Overview and Resources …………………… 34 Watertrail Implementation Strategies