53 West 28Th Street Building, Tin Pan Alley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rise and Fall of Tin Pan Alley (Subotnik, Spr

Music 133: Rise and Fall of Tin Pan Alley (Subotnik, Spr. 2003)—p. 1 MUSIC 133: SEMINAR IN AMERICAN MUSIC: THE RISE AND FALL OF TIN PAN ALLEY Spring Semester, 2003 Rose Rosengard Subotnik COURSE DESCRIPTION: Focusing on the decades between the 1880s and the 1950s, this course examines social, musical and commercial forces behind the emergence and decline of Tin Pan Alley as well as changes in the substance, treatment, and significance of its songs during their years of popularity. Topics addressed include national identity and race relations as well as the difficulties of analyzing popular music. GOALS OF COURSE: The goal of this course is to give you a sound musical, historical, and critical sense of the Tin Pan Alley type of song, of the changes in style and role that characterized such songs over several generations, and of the various kinds of responses they have generated. Questions we will consider include 1) musical ones (e.g. What repertories does the term “Tin Pan Alley song” designate? In what ways is it useful to discuss the musical characteristics of such songs [their history? their structure? the various styles and mediums that made use of such songs? the identity of the artists who presented them?]] How might we assign musical value to this general category of song, and how might we evaluate individual songs within this category? Why is the Tin Pan Alley song typically denigrated in contrast to jazz, blues, and rock music? What happened to this type of song in the late 1940s and the 1950s, both before and during the transition to rock and roll?); and 2) cultural ones (e.g. -

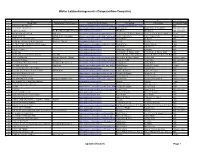

EXCEL LATZKO MUZIK CATALOG for PDF.Xlsx

Walter Latzko Arrangements (Computer/Non-Computer) A B C D E F 1 Song Title Barbershop Performer(s) Link or E-mail Address Composer Lyricist(s) Ensemble Type 2 20TH CENTURY RAG, THE https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/the-20th-century-rag-digital-sheet-music/21705300 Male 3 "A"-YOU'RE ADORABLE www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/a-you-re-adorable-digital-sheet-music/21690032Sid Lippman Buddy Kaye & Fred Wise Male or Female 4 A SPECIAL NIGHT The Ritz;Thoroughbred Chorus [email protected] Don Besig Don Besig Male or Female 5 ABA DABA HONEYMOON Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/aba-daba-honeymoon-digital-sheet-music/21693052Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Arthur Fields & Walter Donovan Female 6 ABIDE WITH ME Buffalo Bills; Chordettes www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/abide-with-me-digital-sheet-music/21674728Henry Francis Lyte Henry Francis Lyte Male or Female 7 ABOUT A QUARTER TO NINE Marquis https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/about-a-quarter-to-nine-digital-sheet-music/21812729?narrow_by=About+a+Quarter+to+NineHarry Warren Al Dubin Male 8 ACADEMY AWARDS MEDLEY (50 songs) Montclair Chorus [email protected] Various Various Male 9 AC-CENT-TCHU-ATE THE POSITIVE (5-parts) https://www.sheetmusicplus.com/title/ac-cent-tchu-ate-the-positive-digital-sheet-music/21712278Harold Arlen Johnny Mercer Male 10 ACE IN THE HOLE, THE [email protected] Cole Porter Cole Porter Male 11 ADESTES FIDELES [email protected] John Francis Wade unknown Male 12 AFTER ALL [email protected] Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Ervin Drake & Jimmy Shirl Male 13 AFTER THE BALL/BOWERY MEDLEY Song Title [email protected] Charles K. -

The Tin Pan Alley Pop Era (1885-Mid 1950'S)

OVERVIEW: The Foundation of Rock And Roll During the Great Migration more than 100,000 African-American laborers moved from the agricultural South to the urban North bringing with them their music and memories. Also, during the 1920’s the phonograph and the rise of commercial radio began to spread Hillbilly music and the Blues. This gave rise to an appreciating of American vernacular music, both white and black. Ultimately, the homogenizing effect of blending several regional musical styles and cultural practices gave birth to 1950’s rock and roll. The Tin Pan Alley Po ra 15-mid 1950’s) “The Great American Songbook” 1940’s Big Bands 1950’s Polar sic New York: “Tin Pan Alley” 14th St. and 2nd Ave. 1 Tin Pan Alley - New York 15-thogh 1940’s) The msic was distribted throgh sheet msic Proessional songwriters dominated the eriod George Gershwin and ole Porter omosers wrote or o msic Broadway and ilm ventally Tin Pan Alley tradition was relaced by the ock and oll tradition Tin Pan Alle – Ke oints 1. Written b a proessional oten non-peroring song-riters 2. ophisticated arrangeent 3. ncopated rhth accents on unepected, eak beats) 4. lever, ell-crated lrics 5. triving or upper-class sensibilities 6. Priar audience Adults 2 “Roots Music” - K oits 1. Riona ou o music 2. tu usicis 3. ot o tut 4. tou o titio 5. o maistream ican ists 6. o t i co cois “Roots Music” = he Blues D Country music he Blues Country Music 1920’s: Mississippi Delta Blues 1920’s: Cowboy Songs 1930’s: rban Blues 1930’s: Hillbilly Music 1940’s: ump Blues 1940’s: Country Swing -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

WINTER 2017 5 Note from the Editor by Kim Decoste, Editor of the VOICE Magazine

Election Perspective: History and the Future pg . 35 ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: A Little Goes a Long Way- This Year’s Soldiers Angels Program pg. 6 TREA Membership Perks pg. 28 Let Us Remember and Honor Our World War II Missing pg. 38 YOUR USAA REWARDS™ CREDIT CARD NOW OFFERS MORE WAYS TO GIVE BACK. Donate your USAA Rewards credit card points to the The ENLISTED Association and help support their mission. Each point donated is transferred to a monetary contribution; every 1,000 rewards points equals $10. Donate Today. USAA.COM/POINTSDONATION USAA means United Services Automobile Association and its affiliates. USAA products are available only in those jurisdictions where USAA is authorized to sell them. Use of the term “member” or “membership” does not convey any eligibility rights for auto and property insurance products, or legal or ownership rights in USAA. Membership eligibility and product restrictions apply and are subject to change. Purchase of a product other than USAA auto or property insurance, or purchase of an insurance policy offered through the USAA Insurance Agency, does not establish eligibility for, or membership in, USAA property and casualty insurance companies. The ENLISTED Association receives financial support from USAA for this sponsorship. 2 This credit card program is issued by USAA Savings Bank, Member FDIC. © 2016 USAA. 231789-0716 The VOICE is the flagship publication of TREA: The En- YOUR USAA REWARDS™ listed Association, located at 1111 S. Abilene Ct., Aurora, CO 80012. CREDIT CARD NOW OFFERS Views expressed in the magazine, and the appearance of advertisement, do not necessarily reflect the opinions of TABLE OF CONTENTS TREA or its board of directors, and do not imply endorse- MORE WAYS TO GIVE BACK. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Aida Overton Walker Performs a Black Feminist Resistance

Restructuring Respectability, Gender, and Power: Aida Overton Walker Performs a Black Feminist Resistance VERONICA JACKSON From the beginning of her onstage career in 1897—just thirty-two years after the end of slavery—to her premature death in 1914, Aida Overton Walker was a vaudeville performer engaged in a campaign to restructure and re-present how African Americans, particularly black women in popular theater, were perceived by both black and white society.1 A de facto third principal of the famous minstrel and vaudeville team known as Williams and Walker (the partnership of Bert Williams and George Walker), Overton Walker was vital to the theatrical performance company’s success. Not only was she married to George; she was the company’s leading lady, principal choreographer, and creative director. Moreover and most importantly, Overton Walker fervently articulated her brand of racial uplift while simultaneously executing the right to choose the theater as a profession at a time when black women were expected to embody “respectable” positions inside the home as housewives and mothers or, if outside the home, only as dressmakers, stenographers, or domestics (see Figure 1).2 Overton Walker answered a call from within to pursue a more lucrative and “broadminded” avocation—one completely outside the realms of servitude or domesticity. She urged other black women to follow their “artistic yearnings” and choose the stage as a profession.3 Her actions as quests for gender equality and racial respectability—or as they are referred to in this article, feminism and racial uplift—are understudied, and are presented here as forms of transnational black resistance to the status quo. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

Florenz Ziegfeld Jr

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ZIEGFELD GIRLS BEAUTY VERSUS TALENT A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Theatre Arts By Cassandra Ristaino May 2012 The thesis of Cassandra Ristaino is approved: ______________________________________ __________________ Leigh Kennicott, Ph.D. Date ______________________________________ __________________ Christine A. Menzies, B.Ed., MFA Date ______________________________________ __________________ Ah-jeong Kim, Ph.D., Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Jeremiah Ahern and my mother, Mary Hanlon for their endless support and encouragement. iii Acknowledgements First and foremost I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis chair and graduate advisor Dr. Ah-Jeong Kim. Her patience, kindness, support and encouragement guided me to completing my degree and thesis with an improved understanding of who I am and what I can accomplish. This thesis would not have been possible without Professor Christine Menzies and Dr. Leigh Kennicott who guided me within the graduate program and served on my thesis committee with enthusiasm and care. Professor Menzies, I would like to thank for her genuine interest in my topic and her insight. Dr. Kennicott, I would like to thank for her expertise in my area of study and for her vigilant revisions. I am indebted to Oakwood Secondary School, particularly Dr. James Astman and Susan Schechtman. Without their support, encouragement and faith I would not have been able to accomplish this degree while maintaining and benefiting from my employment at Oakwood. I would like to thank my family for their continued support in all of my goals. -

Inventory of American Sheet Music (1844-1949)

University of Dubuque / Charles C. Myers Library INVENTORY OF AMERICAN SHEET MUSIC (1844 – 1949) May 17, 2004 Introduction The Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque has a collection of 573 pieces of American sheet music (of which 17 are incomplete) housed in Special Collections and stored in acid free folders and boxes. The collection is organized in three categories: African American Music, Military Songs, and Popular Songs. There is also a bound volume of sheet music and a set of The Etude Music Magazine (32 items from 1932-1945). The African American music, consisting of 28 pieces, includes a number of selections from black minstrel shows such as “Richards and Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels Songster and Musical Album” and “Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik of Alabami)”. There are also pieces of Dixieland and plantation music including “The Cotton Field Dance” and “Massa’s in the Cold Ground”. There are a few pieces of Jazz music and one Negro lullaby. The group of Military Songs contains 148 pieces of music, particularly songs from World War I and World War II. Different branches of the military are represented with such pieces as “The Army Air Corps”, “Bell Bottom Trousers”, and “G. I. Jive”. A few of the delightful titles in the Military Songs group include, “Belgium Dry Your Tears”, “Don’t Forget the Salvation Army (My Doughnut Girl)”, “General Pershing Will Cross the Rhine (Just Like Washington Crossed the Delaware)”, and “Hello Central! Give Me No Man’s Land”. There are also well known titles including “I’ll Be Home For Christmas (If Only In my Dreams)”. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

Annual Gala Concert 2019 the Chicago Paris Cabaret Connexion Tour De France Is Open to Performers and Fans

annual gala concert 2019 The Chicago Paris Cabaret Connexion Tour de France is open to performers and fans. September 12-22, 2019: Ten exciting days in France to tour, sing, Production by Claudia HOMMEL learn and perform with fellow artists * Over 30 hours of master classes and workshops Music direction by * Evening concerts and jam sessions Elizabeth DOYLE and Myron SILBERSTEIN * French cuisine and camaraderie * Free time to explore Montpellier, Sète and Paris bene! tting the SongShop Scholarship Fund, www.cabaretconnexion.org/program_join.php a project of Working in Concert NFP SATURDAY, MAY 4 SUNDAY, MAY 5 Beth Halevy, Carrie Hedges, Caryn Caffarelli, Don Hoffman, Carmen Bodino, Christine Steyer, Claudia Hommel, Daniel Drew Fase, Kimberly Mann, Lynda Gordon, Patrick Davis, Johnson, David M Stephens, Evelyn Danner, Leona Zions, Nadine Susan Dennis, Vivian Beckford with Elizabeth Doyle at the piano Vorenkamp, Ruth Fuerst with Myron Silberstein at the piano Introduced by Claudia Hommel Special guests Jean-Claude Orfali and Cappy Kidd Claudia I’m Old Fashioned Jerome Kern & Johnny Mercer Claudia Lusty May Gabriel Fauré & adapted by Claudia Hommel Vivian It’s a Grand Night for Singing David Times of Your Life Roger Nichols & Bill Lane Richard Rogers & Oscar Hammerstein II (State Fair) Arthur’s Theme Burt Bacharach, Carole Bayer Sager, Drew Singin’ in the Rain Nacio Herb Brown & Arthur Freed Christopher Cross and Peter Allen The Moon Was Yellow Fred E Ahlert & Edger Leslie One in a Million You Sam Dees Kim Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me Bernie Taupin & Elton John Evelyn The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face Ewan MacColl Beth Smile Charlie Chaplin, John Turner & Geoff rey Parsons Christine Tonight Leonard Bernstein & Stephen Sondheim Carrie It’s a Good Day Peggy Lee and Dave Barbour Moon over Bourbon Street Sting Les Champs-Elysees Mike Wilsh & Michael Deighan, Ruth My Sweetheart’s the Man in the Moon / James Thornton Pierre Delano, English translation by Patricia Spaeth The Man in the Moon is a ..