The Linköping Mitre Ecclesiastical Textiles and Episcopal Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

88 Foundation of the Pirita Convent, 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources

88 Ruth Rajamaa Foundation of the Pirita Convent, known to researchers of the Birgittine Order 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources but, together with other Swedish sources, it Ruth Rajamaa is possible to discover new aspects in the Summary relations between the Pirita and Vadstena convents. Abstract: This article is largely based on Vadstena was the mother abbey of the Order Swedish sources and examines the role of of the Holy Saviour, Ordo Sancti Salvatoris. the Vadstena abbey in the history of the The founder, Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303 Pirita convent, from the founding of its 1373), had a revelation in 1346: Christ gave daughter convent in 1407 until the conse- her the constitution of a new order. In 1349, cration of the independent convent in 1431. Birgitta left Sweden and settled in Rome in Various aspects of the Vadstena abbey’s order to personally ask permission from the patronage are pointed out, revealing both pope to found a new order. The Order of the a helpful attitude and interfering guid- Holy Saviour was confirmed in 1370 and ance. Vadstena paid more attention to again in 1378 under the Augustinian Rule, Pirita than to other Birgittine monasteries with the addition of the Rule of the Holy and had many brothers and sisters of its Saviour, Ordo sancti Augustini sancti Sal- monastery there. Such closeness to the vatoris nuncupatus. mother monastery is a totally new pheno- The main aim of the Birgittine Order was menon in the history of researching Pirita, to purify all Christians; it was established and still needs more thorough analysis. -

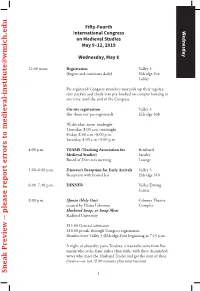

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches

CM 2014 ombrukket3.qxp_CM 30.04.15 15.46 Side 114 The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches JONAS CARLQUIST This article discusses the use of wooden Marian sculptures in Swedish parish churches during the Middle Ages. By analysing the Marian sculptures’ context, design and mate- riality together with vernacular devotional literature, I suggest that these different media together collaborated in the education of the lay congregation about the life of the Virgin and her cult. Together, sculptures and prayers facilitated private meditation. I will use the Madonna of Knutby Church as my leading example. Introduction Located in the Swedish arch-diocese of Uppland, Knutby is a small parish with a 13th century, church situated close to Uppsala. The church’s patron is St Martin of Tours, but its interior also contains many images of the Virgin Mary. Among other objects, the church contains an Apocalyptic Madonna from the late 15th century (according to Swedish history Museum, Stockholm). During the late medieval period in Swe- den, namely in the 15th and 16th centuries, many examples of such Madonnas were locally produced for parish churches, and apocalyptic Madonnas were also imported into Sweden, usually from northern Germany or the netherlands (see for example Andersson 1980: 64–78). In this article, I will discuss the reasons behind the design, the intertextuality (i.e. the shaping of a text’s meaning by another text by for example allusion, quotation), and the congregation’s assumed perception of the Madonna of Knutby to provide a deeper understanding of the general use of wooden Marian sculptures in medieval Sweden. -

Continuity and Change

Continuity and Change PAPERS FROM THE BIRGITTA CONFERENCE AT DARTINGTON 2015 Editors Elin Andersson, Claes Gejrot, E. A. Jones & Mia Åkestam KONFERENSER 93 KUNGL. VITTERHETS HISTORIE OCH ANTIKVITETS AKADEMIEN MIA ÅKESTAM Creating Space Queen Philippa and Art in Vadstena Abbey RINCESS PHILIPPA OF ENGLAND sailed into the harbour of Helsing- borg in September 1406 with ten ships and four balingers. She was 12 P years old, and arrived as queen of her new realms: Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Philippa had already married the King Erik of Pomerania par procuration in Westminster Abbey in December 1405, with the Swedish knight Ture Bengtsson (Bielke) as the king’s deputy at the ceremony. Now the marriage was to be repeated in Lund, this time with the king present. Philippa showed up with a retinue of 204 named persons, all wearing uniform dress in green and scarlet, accordingly furred and lined, with embroidered white crowns and the motto ‘sovereyne’ on one shoulder. Each badge was embroidered in accordance with the carriers’ social position.1 Te English escort exceeded 500 persons with servants and sailors included. Her trousseaux – the dowry – was extensive, and carefully recorded by the Royal Household. It is evident that the queen’s arrival was intended to be impressive. As an English princess, Philippa was also a representative of the Royal House of Lancaster, which naturally involved rank and power. She was the youngest daughter of King Henry IV and Mary de Bohun, born shortly before or on 4 July 1394 (her mother died that day, after giving birth to Philippa). One of her brothers was the famous king Henry V, victor at the battle of Agincourt 1415. -

Diarium Vadstenense: a Late Medieval Memorial Book and Political Chronicle

Diarium Vadstenense: A Late Medieval Memorial Book and Political Chronicle Claes Gejrot The National Archives of Sweden, Stockholm This article deals with the Diarium Vadstenense, a Liber memorialis originating in Vadstena, the abbey founded by Saint Birgitta of Sweden. Written by a succession of Birgittine friars, this parchment manuscript is still preserved in its original form. It records internal, monastic events from the founding of the abbey in the second half of the fourteenth century to the time the last brother left the community, after the Reformation. Glimpses from the world outside the abbey are seen here and there throughout the text. However, during a central part of the fifteenth century, some of the entries were extended, and the writing changes character. These texts can be seen as a more or less continuous chronicle, tendentiously describing the complicated political situation in Sweden in the 1460s, a time marked by wars and conflicts. Indeed, parts of the texts were so controversial that they were later (partly) erased by a cautious medieval ‘editor’. The focus in this article will be on the time frame when the text was written, the personal views and opinions of the writers, confidentiality, political bias and censorship. The Diarium Vadstenense1 – and especially the chronicle parts of its text – will be at the centre of our attention, but let us start from the beginning. Vadstena Abbey was founded by Saint Birgitta (1303– 1373) in the Swedish province of Östergötland and intended for sixty sisters and twenty-five brothers. Not long after the activities began in the abbey in the 1370s,2 a series of brothers began reporting on events inside the monastery and sometimes also on events outside. -

Religious Devotion and Business the Pre-Reformation Enterprise of the Lübeck Presses

ELIZABeTH ANDeRSeN Religious Devotion and Business The Pre-Reformation Enterprise of the Lübeck Presses From the outset, Lübeck was a centre for the new art of printing. This lead- ing position was maintained throughout the Reformation; thus it was that the first complete Lutheran Bible to reach the market in 1533 was printed not in Wittenberg but in Lübeck by Ludwig Dietz and it was a translation into Low rather than High German (illustration 1). The first Lutheran Bible of Sweden (1539, illustration 2), was the work of Jürgen Richolff the Younger, also a printer from Lübeck, and the first Danish Lutheran Bible (1550, illustration 3) was the work again of Ludwig Dietz. The strong lead in religious vernacular printing during the Reformation in the Baltic region rested on the foundations laid by the first generation of printers in Lübeck. The success of the Lübeck printers in the sixteenth century grew out of the particular intersection of busi- ness and devotion established in the fifteenth. The fruitful nature of this inter- section was fostered by a fortuitous combination of political, economic and intellectual conditions which prevailed in the city. Against this background, the focus of what follows is trained on printers who were in business between c. 1470 and c. 1520, in particular Steffen Arndes, Bartholomäus Ghotan and the Mohnkopf Press.1 For the latter, the press of the Brethren of the Common Life in the neighbouring Hanseatic city of Rostock provides a foil which allows the fundamental difference in the business model of the two presses to emerge sharply. -

Ansgar's Final Index 1910-2010

100The St. Ansgar’s BulletinYEARS CD Archives 1910 – 2010 Index by title This index is sorted by title for each article, with its corresponding year of publication. Complete text can be found within the annual Bulletins, located on the St. Ansgar’s Archive CD. Bulletins are arranged by year, and each article within is bookmarked by title, matching this index. Index by Title page 1 of 81 ## 1) Iceland, Made by Fire 1965 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 1) In Sweden 1965 1) Report on Denmark 1962 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 100 Years 2010 100 Years of Norwegian Christianity 1996 1834/'36 - Sacra Paenitentiaria Apostolica (Sacred Apostolic 1936 Penitentiary Office of Indulgence) 1924 -- Fr. Per Waago O.M.I. -- 1990 1991 Bradley, Michael OMI 1958 Catholic Interest Vacation Tour of Scandinavia, The 1957 1958 Picnic At Vikingsborg 1958 Bailey, Elizabeth C. 1959 - Assumptionist Pilgrimage to Scandinavia --- July 18- 1958 Aug. 24 1988 Pilgrimage to Scandinavia, The 1987 & 1988 Halborg, John E. (Father) 1988 St. Ansgar's League's Pilgrimage Tour, The 1989 1996: Five Hundredth Anniversary of Canute Lavard 1997 1st Danish Oblate Father 1964 1st Scandinavian Beatified Since Reformation 1989 Erlandson, Greg 2) Ecumenical Vespers in Hamburg 1965 2) Luleå Serves Three Provinces 1965 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 2) Report on Sweden (Continued from page 7) 1962 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 25th Anniversary of Brigittines in U.S.A. 1982 Whealon, John F. (Most Rev.) 3) Report on Norway (Continued from page 13) 1962 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 3) Snow Peaks of North Norway 1965 Dwight, John T. (Editor) 30 Years a Bishop in Finland 1964 Brady, Anna 4) Finland is Farthest East 1965 Dwight, John T. -

Leeds Studies in English

Leeds Studies in English Article: Susan Powell, 'Preaching at Syon Abbey', 'Preaching at Syon Abbey', Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 31 (2000), 229-67 Permanent URL: https://ludos.leeds.ac.uk:443/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=123753&silo_library=GEN01 Leeds Studies in English School of English University of Leeds http://www.leeds.ac.uk/lse Preaching at Syon Abbey1 Susan Powell The monastery of the Holy Saviour, St Mary the Virgin and St Bridget, known as Syon Abbey, was founded by Henry V in 1415 and was the only house of the Bridgettine Order to be established in England; it was dissolved in 1539.2 During the little more than a century of its existence, the Bridgettines at Syon acquired a powerful reputation for intellectual and literary activity, a reputation also held by Henry's second foundation, the Charterhouse of Jesus of Bethlehem on the other side of the Thames at Sheen. One difference between the two orders, however, lay in their relationship with the outside world. The Bridgettines were specifically enjoined to preach to the laity, whereas the Carthusians were forbidden to do so.4 The present study took its impetus from my curiosity as to whether three English sermons printed by Caxton in his 1491 edition of the Festial might be products of Syon.5 Their context was Bridgettine, and there was reason to assume that the sermons themselves might be Bridgettine. Although published studies of Syon Abbey stressed the importance of the preaching there, they proved to be surprisingly reticent about what Syon sermons were actually like. -

54Th International Congress on Medieval Studies

54th International Congress on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Western Michigan University 1903 W. Michigan Ave. Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5432 wmich.edu/medieval 2019 i Table of Contents Welcome Letter iii Registration iv–v On-Campus Housing vi–vii Food viii–ix Travel x Driving and Parking xi Logistics and Amenities xii–xiii Varia xiv Off-Campus Accommodations xv Hotel Shuttle Routes xvi Hotel Shuttle Schedules xvii Campus Shuttles xviii Diversity and Inclusion xix Exhibits Hall xx Exhibitors xxi Social Media xxii Reception of the Classics in the Middle Ages Lecture xxiii Mostly Medieval Theatre Festival xxiv–xxv Plenary Lectures xxvi Exhibition of Medieval Manuscripts xxvii Advance Notice—2020 Congress xxviii The Congress: How It Works xxix Travel Awards xxx The Otto Gründler Book Prize xxxi Richard Rawlinson Center and Center for Cistercian and Monastic Studies xxxii M.A. Program in Medieval Studies xxxiii Medieval Institute Publications xxxiv–v Endowment and Gift Funds xxxvi 2019 Congress Schedule of Events 1–193 Index of Sponsoring Organizations 194–198 Index of Participants 199–214 Maps and Floor Plans M-1 – M-9 List of Advertisers Advertising A-1 – A-39 Color Maps ii Dear colleagues, We’re about to get some warmer weather soon, so I’m told, as the semester draws to an end here at Western Michigan University. Today, the sun is out and the end of the fall semester makes me think of the spring, when Sumer may be Icumen In and friends new and old will join us at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in May. -

Heymericus De Campo: Dyalogus Super Reuelacionibus Beate Birgitte a Critical Edition with an Introduction

Heymericus de Campo: Dyalogus super Reuelacionibus Beate Birgitte A Critical Edition with an Introduction by ANNA FREDRIKSSON ADMAN Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Latin presented at Uppsala University in 2003 ABSTRACT Fredriksson Adman, A. 2003: Heymericus de Campo: Dyalogus super Reuelacionibus beate Birgitte. A Critical Edition with an Introduction. 242 p Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5694-4 This dissertation contains an edition of Dyalogus super Reuelacionibus beate Birgitte, which is a discussion and defence of the Revelations (Reuelaciones) of St. Birgitta of Sweden (ca. 1303-1373). In legal proceedings at the Council of Basle (1431-1449), the Reuelaciones were accused of heresy, examined and defended. Among the defenders was Heymericus de Campo (1395-1460), who at that time was professor of theology at the University of Cologne. In addition to the formal examination reports, Heymericus wrote a dialogue on the subject. The Dyalogus, which was probably composed as a contribution to a debate, is tentatively dated to have been written between October 1434 and February 17, 1435. The main part of Dyalogus consists of 123 text passages extracted from the Reuelaciones and accused of heresy, and Heymericus’ defence of these text passages. The aim of the defence is to prove that the Reuelaciones are truly orthodox and thus inspired by God. In addition, Heymericus intends to display the reasons and arguments the impugners had for questioning the Reuelaciones. Dyalogus and the other defences were read and copied foremost within the Birgittine order. The judgement passed at the proceedings called for a commentary before the Reuelaciones could be disseminated to the whole of their extent.