Leeds Studies in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

The Linköping Mitre Ecclesiastical Textiles and Episcopal Identity

CHAPTER 9 THE LINKÖPING MITRE ECCLESIASTICAL TEXTILES AND EPISCOPAL IDENTITY Ingrid Lunnan Nødseth Questions of agency have been widely discussed in art history studies in recent decades, with scholars such as Alfred Gell and W. T. Mitchell arguing that works of art possess the qualities or powers of living beings. Recent scholar ship has questioned whether Max Weber’s notion of charisma as a personal quality can be extended to the realm of things such as charismatic objects or charismatic art. Textiles are particularly interesting in this regard, as clothing transforms and extends the corporal body acting as a ‘social skin’, this prob lematizes the human/object divide. As such, ecclesiastical dress could be con sidered part of the priest’s social body, his identity. The mitre was especially symbolic and powerful as it distinguished the bishop from the lower ranks of the clergy. This article examines the richly decorated Linköping mitre, also known as Kettil Karlsson’s mitre as it was most likely made for this young and ambitious bishop in the 1460s. I argue that the aesthetics and rhetoric of the Linköping mitre created charismatic effects that could have contributed to the charisma of Kettil Karlsson as a religious and political leader. This argument, however, centers not so much on charismatic objects as on the relationship between personal charisma and cultural objects closely identified with char ismatic authority. The Swedish rhyme chronicle Cronice Swecie describes [In Linköping I laid down my episcopal vestments how bishop Kettil Karlsson in 1463 stripped himself of and took up both shield and spear / And equipped his episcopal vestments (biscopsskrud) in the cathedral myself as a warrior who can break lances in combat.] of Linköping, only to dress for war with shield and spear (skiöll och spiwt) like any man who could fight well with This public and rhetorical event transformed the young a lance in combat: bishop from a man of prayer into the leader of a major army. -

Letters from Early Modern English Nuns in Exile

“NO OTHER MEANS THAN BY PEN”: LETTERS FROM EARLY MODERN ENGLISH NUNS IN EXILE by Tanyss Sharp, B.A. Honours A thEsis submittEd to thE Faculty of GraduatE and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillmEnt of thE requiremEnts for thE dEgreE of MastEr of Arts in History CarlEton UnivErsity Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Tanyss Sharp ii Abstract This thesis explores how early modern English nuns in exilE on the European continent purposEfully utilizEd lEttEr writing as a stratEgy of communication with the outside world. Cut off from their homEland and familiEs by both geographic distancE and physical Enclosure, lEttErs provided womEn religious with a mEdium to ensure their convents’ survival and presErve English Catholicism. This critical analysis of nuns’ lEttErs reveals the multidimEnsional nature and intEntional construction of their correspondencE. Nuns made deliberatE epistolary choicEs. They employed stratEgic language, utilizEd flattEry and humility, as wEll as exaggeration and gossip to achiEve their objEctives. A comparison of individual epistolary experiEncEs demonstratEs that lEttErs wEre vital for maintaining familial and kinship tiEs, financial and spiritual economiEs, political EngagemEnt, and the transnational diffusion of information. iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not have beEn complEtEd without the support and encouragemEnt of numErous peoplE. This thesis was funded in part by SSHRC and OGS, which made it significantly EasiEr to accomplish and allowEd for a vital resEarch trip. During my timE in England and Belgium the assistancE of thosE at the British Library, National Archives, BodlEian Library, Ushaw CollEge, Ghent StatE Archives, ArchdiocEsE of MEchelEn-BrussEls and Bisschoppelijk ArchiEf Bruges was invaluablE to my resEarch ExperiEncE. In particular, I would like to thank Abbot GEoffrey Scott of Douai Abbey for his timE and allowing me accEss to his archive. -

88 Foundation of the Pirita Convent, 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources

88 Ruth Rajamaa Foundation of the Pirita Convent, known to researchers of the Birgittine Order 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources but, together with other Swedish sources, it Ruth Rajamaa is possible to discover new aspects in the Summary relations between the Pirita and Vadstena convents. Abstract: This article is largely based on Vadstena was the mother abbey of the Order Swedish sources and examines the role of of the Holy Saviour, Ordo Sancti Salvatoris. the Vadstena abbey in the history of the The founder, Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303 Pirita convent, from the founding of its 1373), had a revelation in 1346: Christ gave daughter convent in 1407 until the conse- her the constitution of a new order. In 1349, cration of the independent convent in 1431. Birgitta left Sweden and settled in Rome in Various aspects of the Vadstena abbey’s order to personally ask permission from the patronage are pointed out, revealing both pope to found a new order. The Order of the a helpful attitude and interfering guid- Holy Saviour was confirmed in 1370 and ance. Vadstena paid more attention to again in 1378 under the Augustinian Rule, Pirita than to other Birgittine monasteries with the addition of the Rule of the Holy and had many brothers and sisters of its Saviour, Ordo sancti Augustini sancti Sal- monastery there. Such closeness to the vatoris nuncupatus. mother monastery is a totally new pheno- The main aim of the Birgittine Order was menon in the history of researching Pirita, to purify all Christians; it was established and still needs more thorough analysis. -

Introduction

1 I n t r o d u c t i o n eligious sisters and nuns, known collectively as women religious,1 have always operated in a liminal place in church and popular R culture. Nuns for centuries maintained a spiritual capital that gave them a special role in the life of the Catholic Church. Th ough some individual abbesses may have wielded signifi cant power, women religious were never canonically members of the clergy. Th ey had, however, in popular understanding, a ‘higher calling’. 2 Th rough the institutions they managed, female religious had enormous infl uence in shaping generations of Catholics. Th ey were, by the nineteenth century, 1 Th e term religious life refers to a form of life where men or women take three vows, of poverty, chastity and obedience, and are members of a particular religious institute which is governed by a rule and constitution. Catholic religious life has traditionally been divided into two main categories: orders of contemplative nuns whose work is prayer of the Divine Offi ce inside the cloister and ‘active’ congregations of religious sisters whose ministry or apostolate (traditionally teaching, nursing and social welfare) is outside the cloister. Th e terms sisters and nuns were are oft en used interchangeably, although with the codifi cation of Canon Law in 1917 the term sister came to defi ne women who took simple vows and worked outside the cloister and the term nun came to refer to contemplatives who took solemn vows and lived a life of prayer behind cloister walls. Catholic religious sisters and nuns are oft en referred to collectively as women religious. -

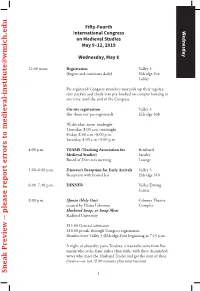

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD's “Catholic Spirituality” This Work Is a Study in Catholic Spirituality. Spirituality Is Concerned With

SPIRITUALITY: ABCD’s “Catholic Spirituality” This work is a study in Catholic spirituality. Spirituality is concerned with the human subject in relation to God. Spirituality stresses the relational and the personal though does not neglect the social and political dimensions of a person's relationship to the divine. The distinction between what is to be believed in the do- main of dogmatic theology (the credenda) and what is to be done as a result of such belief in the domain of moral theology (the agenda) is not always clear. Spirituality develops out of moral theology's concern for the agenda of the Christian life of faith. Spirituality covers the domain of religious experience of the divine. It is primarily experiential and practical/existential rather than abstract/academic and conceptual. Six vias or ways are included in this compilation and we shall take a look at each of them in turn, attempting to highlight the main themes and tenets of these six spiritual paths. Augustinian Spirituality: It is probably a necessary tautology to state that Augus- tinian spirituality derives from the life, works and faith of the African Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430). This spirituality is one of conversion to Christ through caritas. One's ultimate home is in God and our hearts are restless until they rest in the joy and intimacy of Father, Son and Spirit. We are made for the eternal Jerusalem. The key word here in our earthly pilgrimage is "conversion" and Augustine describes his own experience of conversion (metanoia) biographically in Books I-IX of his Confessions, a spiritual classic, psychologically in Book X (on Memory), and theologically in Books XI-XIII. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (With Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia)

religions Article A Brief History of Medieval Monasticism in Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia) Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig Jakobsen Department of Nordic Studies and Linguistics, University of Copenhagen, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Abstract: Monasticism was introduced to Denmark in the 11th century. Throughout the following five centuries, around 140 monastic houses (depending on how to count them) were established within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Duchy of Schleswig, the Principality of Rügen and the Duchy of Estonia. These houses represented twelve different monastic orders. While some houses were only short lived and others abandoned more or less voluntarily after some generations, the bulk of monastic institutions within Denmark and its related provinces was dissolved as part of the Lutheran Reformation from 1525 to 1537. This chapter provides an introduction to medieval monasticism in Denmark, Schleswig, Rügen and Estonia through presentations of each of the involved orders and their history within the Danish realm. In addition, two subchapters focus on the early introduction of monasticism to the region as well as on the dissolution at the time of the Reformation. Along with the historical presentations themselves, the main and most recent scholarly works on the individual orders and matters are listed. Keywords: monasticism; middle ages; Denmark Citation: Jakobsen, Johnny Grandjean Gøgsig. 2021. A Brief For half a millennium, monasticism was a very important feature in Denmark. From History of Medieval Monasticism in around the middle of the 11th century, when the first monastic-like institutions were Denmark (with Schleswig, Rügen and introduced, to the middle of the 16th century, when the last monasteries were dissolved Estonia). -

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook

CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook Event Data Project Department of Political Science Pennsylvania State University Pond Laboratory University Park, PA 16802 http://eventdata.psu.edu/ Philip A. Schrodt (Project Director): < schrodt@psu:edu > (+1)814.863.8978 Version: 1.1b3 March 2012 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.0.1 Events . .1 1.0.2 Actors . .4 2 VERB CODEBOOK 6 2.1 MAKE PUBLIC STATEMENT . .6 2.2 APPEAL . .9 2.3 EXPRESS INTENT TO COOPERATE . 18 2.4 CONSULT . 28 2.5 ENGAGE IN DIPLOMATIC COOPERATION . 31 2.6 ENGAGE IN MATERIAL COOPERATION . 33 2.7 PROVIDE AID . 35 2.8 YIELD . 37 2.9 INVESTIGATE . 43 2.10 DEMAND . 45 2.11 DISAPPROVE . 52 2.12 REJECT . 55 2.13 THREATEN . 61 2.14 PROTEST . 66 2.15 EXHIBIT MILITARY POSTURE . 73 2.16 REDUCE RELATIONS . 74 2.17 COERCE . 77 2.18 ASSAULT . 80 2.19 FIGHT . 84 2.20 ENGAGE IN UNCONVENTIONAL MASS VIOLENCE . 87 3 ACTOR CODEBOOK 89 3.1 HIERARCHICAL RULES OF CODING . 90 3.1.1 Domestic or International? . 91 3.1.2 Domestic Region . 91 3.1.3 Primary Role Code . 91 3.1.4 Party or Speciality (Primary Role Code) . 94 3.1.5 Ethnicity and Religion . 94 3.1.6 Secondary Role Code (and/or Tertiary) . 94 3.1.7 Specialty (Secondary Role Code) . 95 3.1.8 Organization Code . 95 3.1.9 International Codes . 95 i CONTENTS ii 3.2 OTHER RULES AND FORMATS . 102 3.2.1 Date Restrictions . 102 3.2.2 Actors and Agents . -

Why Are Nuns Funny?

Why Are Nuns Funny? Frances E. Dolan ! !" #"$%&"' & $#"#(&)!*" *( )+* a;er the Reformation, the nun was a stock <gure in a surprisingly wide range of representations. She appears in mis - chievous ballads; in comedies (where, from the poisoned nuns in !e Jew of Malta to the wise abbess in !e Comedy of Errors, the nun is either silly or benign rather than a female version of the misguided friars and villainous cardinals of tragedy); in earnest exposés of Catholic corruption; in erotic elaborations of what might happen inside the cloister and inside the confessional; in the occasional biography of a nun by her con - fessor or abbess; in theological treatises and guides addressed to her; and in the letters and other writings nuns themselves composed. Except for texts produced by and for Catholics, most of these texts provoke laughter at the nun’s failed attempts at chastity, her misguided obedience, her superstition, and her presumption to authority.= Since nuns were as various as anyone else, and representations of them spanned centuries, appearing in a range of genres and addressed to a great variety of readers, the polemi- cal project of ridiculing the nun needs to be scrutinized rather than taken as given. >e laughable nun is exposed to hostile view from the outside. Her exposure is designed in part to secure the alienated position from which one observes and ridicules her. From this viewpoint, she <gures that part of Catholicism that is to be d ismissed rather than feared: the absurdity of female authority and separatism; the inevitable eruption of repression into license; the mindless submission to corrupt leaders. -

The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches

CM 2014 ombrukket3.qxp_CM 30.04.15 15.46 Side 114 The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches JONAS CARLQUIST This article discusses the use of wooden Marian sculptures in Swedish parish churches during the Middle Ages. By analysing the Marian sculptures’ context, design and mate- riality together with vernacular devotional literature, I suggest that these different media together collaborated in the education of the lay congregation about the life of the Virgin and her cult. Together, sculptures and prayers facilitated private meditation. I will use the Madonna of Knutby Church as my leading example. Introduction Located in the Swedish arch-diocese of Uppland, Knutby is a small parish with a 13th century, church situated close to Uppsala. The church’s patron is St Martin of Tours, but its interior also contains many images of the Virgin Mary. Among other objects, the church contains an Apocalyptic Madonna from the late 15th century (according to Swedish history Museum, Stockholm). During the late medieval period in Swe- den, namely in the 15th and 16th centuries, many examples of such Madonnas were locally produced for parish churches, and apocalyptic Madonnas were also imported into Sweden, usually from northern Germany or the netherlands (see for example Andersson 1980: 64–78). In this article, I will discuss the reasons behind the design, the intertextuality (i.e. the shaping of a text’s meaning by another text by for example allusion, quotation), and the congregation’s assumed perception of the Madonna of Knutby to provide a deeper understanding of the general use of wooden Marian sculptures in medieval Sweden.