The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I. Paleografi, Boktryck Och Bokhistoria

I. Paleografi, boktryck och bokhistoria. 1. Paleografi, handskrifts- och urkundsväsen samt kronologi. 1. AHNLUND, N., Nils Rabenius (1648-1717). Studier i svensk historiografi. Stockh. 1927. 172 s., 1 pl. 8°. Om Nils Babenius' urkundsförfalskningar. Ree. 13. Boilmuus i SvT 1927, s. 295-298. - E. NOREEN i Korrespondens maj 1939, omtr. i förf:ns Från Birgitta till Piraten (1912), s. 84-89. 2. BECKMAN, BJ., Dödsdag och anniversarieda,_« i Norden med särskild hänsyn till Uppsalakalendariet 1344. KHÅ 1939, s. 112- 145. 3. BECKMAN, N., En förfalskning. ANF 1921/22, s. 216. Dipl. Svoc. I, s. 321. Ordet Abbutis i »Ogeri Abbatis» ändrat t. Rabbai (av Nils 11abenins). 4. Cod. Holm. B 59. ANF 57 (1943), s. 68-77. 5. BRONDUM-NIELSEN, J., Den nordiske Skrift. I: Haandbog i Bibl.-kundskab udg. af S. Dahl, Opl. 3, Bd 1 (1924), s. 51-90. 6. nom, G. T., Studies in scandinavian paleography 1-3. Journ. of engl. a. germ. philol., 14 (1913), s. 530-543; 16 (1915), s. 416-436. 7. FRANSEN, N., Svensk mässa präntad på, pergament. Graduale-kyriale (ordinarium missaa) på, svenska från 1500-talet. Sv. Tidskr. f. musikforskn. 9 (1927), s. 19-38. 8. GRANDINSON, K.-G., S:t Peters afton och andra date- ringar i Sveriges medeltidshandlingar. HT 1939, s. 52-59. 9. HAArANEN, T., Die Neumenfragmente der Universitäts- bibliothek Helsingfors. Eine Studie zur ältesten nordischen Musik- geschichte. Ak. avh. Hfors 1924. 114 s. 8°. ( - Helsingfors uni- versitetsbiblioteks skrifter 5.) Rec. C. F. HENNERBERG i NTBB 12 (1925), s. 45--49. 10. ---, Verzeichnis der mittelalterlichen Handschriften- fragmente in der Universitätsbibliothek zu Helsingfors I. -

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

The Linköping Mitre Ecclesiastical Textiles and Episcopal Identity

CHAPTER 9 THE LINKÖPING MITRE ECCLESIASTICAL TEXTILES AND EPISCOPAL IDENTITY Ingrid Lunnan Nødseth Questions of agency have been widely discussed in art history studies in recent decades, with scholars such as Alfred Gell and W. T. Mitchell arguing that works of art possess the qualities or powers of living beings. Recent scholar ship has questioned whether Max Weber’s notion of charisma as a personal quality can be extended to the realm of things such as charismatic objects or charismatic art. Textiles are particularly interesting in this regard, as clothing transforms and extends the corporal body acting as a ‘social skin’, this prob lematizes the human/object divide. As such, ecclesiastical dress could be con sidered part of the priest’s social body, his identity. The mitre was especially symbolic and powerful as it distinguished the bishop from the lower ranks of the clergy. This article examines the richly decorated Linköping mitre, also known as Kettil Karlsson’s mitre as it was most likely made for this young and ambitious bishop in the 1460s. I argue that the aesthetics and rhetoric of the Linköping mitre created charismatic effects that could have contributed to the charisma of Kettil Karlsson as a religious and political leader. This argument, however, centers not so much on charismatic objects as on the relationship between personal charisma and cultural objects closely identified with char ismatic authority. The Swedish rhyme chronicle Cronice Swecie describes [In Linköping I laid down my episcopal vestments how bishop Kettil Karlsson in 1463 stripped himself of and took up both shield and spear / And equipped his episcopal vestments (biscopsskrud) in the cathedral myself as a warrior who can break lances in combat.] of Linköping, only to dress for war with shield and spear (skiöll och spiwt) like any man who could fight well with This public and rhetorical event transformed the young a lance in combat: bishop from a man of prayer into the leader of a major army. -

88 Foundation of the Pirita Convent, 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources

88 Ruth Rajamaa Foundation of the Pirita Convent, known to researchers of the Birgittine Order 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources but, together with other Swedish sources, it Ruth Rajamaa is possible to discover new aspects in the Summary relations between the Pirita and Vadstena convents. Abstract: This article is largely based on Vadstena was the mother abbey of the Order Swedish sources and examines the role of of the Holy Saviour, Ordo Sancti Salvatoris. the Vadstena abbey in the history of the The founder, Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303 Pirita convent, from the founding of its 1373), had a revelation in 1346: Christ gave daughter convent in 1407 until the conse- her the constitution of a new order. In 1349, cration of the independent convent in 1431. Birgitta left Sweden and settled in Rome in Various aspects of the Vadstena abbey’s order to personally ask permission from the patronage are pointed out, revealing both pope to found a new order. The Order of the a helpful attitude and interfering guid- Holy Saviour was confirmed in 1370 and ance. Vadstena paid more attention to again in 1378 under the Augustinian Rule, Pirita than to other Birgittine monasteries with the addition of the Rule of the Holy and had many brothers and sisters of its Saviour, Ordo sancti Augustini sancti Sal- monastery there. Such closeness to the vatoris nuncupatus. mother monastery is a totally new pheno- The main aim of the Birgittine Order was menon in the history of researching Pirita, to purify all Christians; it was established and still needs more thorough analysis. -

![Kemivandring ‐ Uppsala]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0090/kemivandring-uppsala-1460090.webp)

Kemivandring ‐ Uppsala]

Uppsala Universitet [KEMIVANDRING ‐ UPPSALA] En idéhistorisk vandring med nedslag i kemins Uppsala och historiska omvärld i urval. Karta: 1. Academia Carolina, Riddartorget 2. Gustavianum 3. Skytteanum 4. Fängelset vid domtrappan 5. Kungliga vetenskaps‐societeten 6. St. Eriks källa, akademikvarnen 7. Starten för branden 1702 8. Celsiushuset 9. Scheeles apotek (revs 1960) 10. Gamla kemikum, Wallerius/Bergman 11. Carolina Rediviva 12. Nya Kemikum/Engelska parken 13. The Svedberg laboratoriet 14. BMC, Uppsala Biomedicinska centrum 15. Ångströmlaboratoriet Uppsala Universitet [KEMIVANDRING ‐ UPPSALA] Uppsala universitet: kort historik[Karta: 1‐4] Uppsala universitet grundades 1477 av katolska kyrkan som utbildningsinstitution för präster och teologer. Det är nordens äldsta universitet och var vid tidpunkten världens nordligaste universitet. Domkyrkorna utbildade präster men för högre utbildningar var svenskar från 1200‐ talet och framåt tvungna att studera vid utländska universitet i till exempel Paris eller Rostock. Den starkast drivande kraften för bildandet av Uppsala universitet var Jakob Ulvsson som var Sveriges ärkebiskop mellan år 1469‐1515 och därmed den som innehaft ämbetet längst (46 år). Vid domkyrkan mot riddartorget finns en staty av Jakob Ulvsson av konstnären och skulptören Christian Eriksson. Statyns porträttlikhet med Ulvsson är förstås tvivelaktig eftersom man inte vet hur Jakob Ulvsson såg ut. Konstnären studerade i Paris tillsammans med Nathan Söderblom och det sägs att Eriksson hade honom som förebild för Ulvsson statyn och som därmed fick mycket lika ansiktsdrag som Söderblom. (Nathan Söderblom var ärkebiskop i Uppsala 1914‐ 1931, grundade den Ekumeniska rörelsen och fick Nobels fredspris 1930). Till en början bestod undervisningen vid Uppsala universitet främst av filosofi, juridik och teologi. Någon teknisk eller naturvetenskap utbildning fanns inte vid denna tidpunkt. -

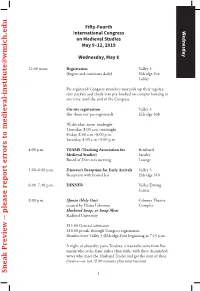

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

Domkyrkoplan. Belysningsarbeten Vid Domkapitelhuset Och S:Ta Barbaras Kapell

Domkyrkoplan Belysningsarbeten vid Domkapitelhuset och S:ta Barbaras kapell RAÄ 88:1 Domkyrkoplan Uppsala Uppland Anna Ölund 2 Upplandsmuseets rapporter 2009:35 Domkyrkoplan Belysningsarbeten vid Domkapitelhuset och S:ta Barbaras kapell RAÄ 88:1 Domkyrkoplan Uppsala Uppland Anna Ölund Upplandsmuseets rapporter 2009:35 3 Omslagsbild: Schaktningsarbete för ny belysning kring domkyrkan i Uppsala. Foto mot väster av Anna Ölund, Upplandsmuseet. Upplandsmuseets rapporter 2009:35 Arkeologiska avdelningen ISSN 1654-8280 Renritning, planer och foton: Anna Ölund, Joakim Kjellberg och Ronnie Carlsson Planer mot norr om inget annat anges. © Upplandsmuseet, 2009 Upplandsmuseet, S:t Eriks gränd 6, 753 10 Uppsala Telefon 018 - 16 91 00. Telefax 018 - 69 25 09 www.upplandsmuseet.se 4 Upplandsmuseets rapporter 2009:35 Innehåll Inledning 6 Bakgrund 7 Arbetsföretaget 7 Tidigare undersökningar 8 Undersökningsresultat 10 A1 – Terrasseringsmur 10 Runstenarna 10 A2 – Domkapitelhuset 12 A3 – S:ta Barbaras kapell 14 Fynd 17 Sammanfattning 18 Administrativa uppgifter 18 Referenser 19 Upplandsmuseets rapporter 2009:35 5 Inledning Efter beslut 2008-04-01 från kulturmiljöenheten, länsstyrelsen i Uppsala län (lstn dnr 431-1952-08 / 431-1953-08) har Upplandsmuseet, avdelningen för arkeologiska undersökningar, utfört en arkeologisk schaktningsövervakning i samband med anläggningsarbeten runt domkyrkan i Uppsala (figur 1 och 2). Beställare var Uppsala kyrkliga samfällighet, som även bekostat undersökningen. Den arkeologiska schaktningsövervakningen skedde kontinuerligt under maj till augusti 2008. Den utfördes av Bent Syse, Joakim Kjellberg och Anna Ölund. Behjälplig vid arbetet var även Örjan Mattson. Rapporten har sammanställts av Anna Ölund. Figur 1. Översikten visar Uppsala stads centrala delar. Cirkeln markerar domkyrkan och det aktuella området. Vid schaktningsövervakningen påträffades murrester både norr och söder om domkyrkan. -

Kulturen 1995 Bokkulturen I Lund

Kulturen 1995 Bokkulturen KULTUREN 1995 EN ÅRSBOK TILL MEDLEMMARNA AV KULTURHISTORISKA FÖRENINGEN i Lund FÖR SÖDRA SVERIGE Bilden på omslaget visar sätteriet i Berlings Stilgjuteri Lund. Bild sid. 6 Lapidariet Ansvarig utgivare: Margareta Alin Huvudredaktör: Nils Nilsson Redaktion: Eva Lis Bjurman, Nils Nilsson samt Per S. Ridderstad. Foto: La rs Westrup Kulturen, där inte annan institution angives Form: Christer Strandberg Upplaga: 22000 ex Typsnitt: Berling Tryck: BTJ Tryck AB, Lund Repro:Sydrepro, Landskrona Papper: Linne ISSN 0454-5915 Innehåll MARGARETA ALIN 7 Kan museer vara visionära? OLOF SUNDBY 17 Stenar som talar NILS NILSSON 22 Berlingska huset PER S. RIDDERSTAD 25 Skriftkultur, bokkultur, tryckkultur PER EKSTRÖM 45 Skriptoriet i Laurentiusklostret NILS NILSSON 59 Gutenberg och boktryckarkonsten NILS NILSSON 6r Handpressen PER S . RIDDERSTAD 64 Lundatryckerier GÖRAN LARSSON 90 Försvenskningen åv de östdanska landskapen 1658 - 1719 STEINGRiMUR JONSSON 97 Gästtryckaren PER S . RIDDERSTAD 99 Inte tryckt i Lund NILS NILSSON 102 Snällpressen CHRISTIAN AXEL- N ILSSON ros Berlings Stilgjuteri i Lund PER S. RIDDERSTAD 127 Sättmaskinen LARS OLSSON 130 Typograferna i Lund vid sekelskiftet NILS N ILSSON 139 Avlatsbrevet - den första blanketten INGMAR BROHED 143 Katekesen som folkbok PER S . RIDDERSTAD 155 Tryckta pengar PER RYDEN 159 Tidningar i Lund EVA LIS BJURMAN 177 En bokhandlare kommer till staden GÖTE KLINGBERG 191 Barnböcker /rån Lund STAFFAN SÖDERBERG 205 Till samhällets tjänst 21 0 Kulturens verksamhet l 994 226 Donatorer l 994 Kan museer vara visionära? nMal och råttor ska inte bestämma vad vi minns!« Så skrev man i den statliga museiutredningen Minne och bildning 1994 om nvårdberget« - d.v.s . de stora föremålssamlingarna i sven ska museimagasin. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

Denmark and the Crusades 1400 – 1650

DENMARK AND THE CRUSADES 1400 – 1650 Janus Møller Jensen Ph.D.-thesis, University of Southern Denmark, 2005 Contents Preface ...............................................................................................................................v Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 Crusade Historiography in Denmark ..............................................................................2 The Golden Age.........................................................................................................4 New Trends ...............................................................................................................7 International Crusade Historiography...........................................................................11 Part I: Crusades at the Ends of the Earth, 1400-1523 .......................................................21 Chapter 1: Kalmar Union and the Crusade, 1397-1523.....................................................23 Denmark and the Crusade in the Fourteenth Century ..................................................23 Valdemar IV and the Crusade...................................................................................27 Crusades and Herrings .............................................................................................33 Crusades in Scandinavia 1400-1448 ..............................................................................37 Papal Collectors........................................................................................................38 -

The 'Long Reformation' in Nordic Historical Research

1 The ‘long reformation’ in Nordic historical research Report to be discussed at the 28th Congress of Nordic Historians, Joensuu 14-17 August 2014 2 Preface This report is written by members of a working group called Nordic Reformation History Working Group, that was established as a result of a round table session on the reformation at the Congress of Nordic Historians in Tromsø in Norway in August 2011. The purpose of the report is to form the basis of discussions at a session on “The ‘long reformation’ in Nordic historical research” at the Congress of Nordic Historians in Joensuu in Finland in August 2014. Because of its preliminary character the report must not be circulated or cited. After the congress in Joensuu the authors intend to rework and expand the report into an anthology, so that it can be published by an international press as a contribution from the Nordic Reformation History Working Group to the preparations for the celebration in 2017 of the 500 years jubilee of the beginning of the reformation. Per Ingesman Head of the Nordic Reformation History Working Group 3 Table of contents Per Ingesman: The ’long reformation’ in Nordic historical research – Introduction – p. 4 Otfried Czaika: Research on Reformation and Confessionalization – Outlines of the International Discourse on Early Modern History during the last decades – p. 45 Rasmus Dreyer and Carsten Selch Jensen: Report on Denmark – p. 62 Paavo Alaja and Raisa Maria Toivo: Report on Finland – p. 102 Hjalti Hugason: Report on Iceland – (1) Church History – p. 138 Árni Daníel Júlíuson: Report on Iceland – (2) History – p. -

Language Choice in Scientific Writing: the Case of Mathematics At

Normat. Nordisk matematisk tidskrift 61:2–4, 111–132 Published in March 2019 Language choice in scientific writing: The case of mathematics at Uppsala University and a Nordic journal Christer Oscar Kiselman Abstract. For several centuries following its founding in 1477, all lectures and dissertations at Uppsala University were in Latin. Then, during one century, from 1852 to 1953, several languages came into use: there was a transition from Latin to Swedish, and then to French, German, and English. In the paper this transition is illustrated by language choice in doctoral theses in mathematics and in a Nordic journal. 1. Introduction The purpose of this note is to show how language choice in mathematical disser- tations presented at Uppsala University changed during one century, from 1852 to 1953—a rapid change in comparison with the more stable situation during the cen- turies 1477–1852. We shall also take a look at languages chosen by mathematicians in Sweden in the journal Acta Mathematica from its start in 1882 and up to 1958. This study was presented at the Nitobe Symposium in Reykjav´ık(2013 July 18– 20) entitled Languages and Internationalization in Higher Education: Ideologies, Practices, Alternatives, organized by the Center for Research and Documentation on World Language Problems (CED). 2. A beginning in the vernacular of the learned In a bull dated 1477 February 27, Pope Sixtus IV granted permission to the Arch- bishop of Uppsala, Jakob Ulvsson, to establish a university there.1 The Archbishop was appointed Chancellor of the new university, which was the first in northern Europe and remained the northernmost for 163 years, until the founding in 1640 of Sweden’s third university in Abo˚ (now Turku in Finland).