Continuity and Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Municipal Energy Planning and Energy Efficiency

Municipal Energy Planning and Energy Efficiency Jenny Nilsson, Linköping University Anders Mårtensson, Linköping University ABSTRACT Swedish law requires local authorities to have a municipal energy plan. Each municipal government is required to prepare and maintain a plan for the supply, distribution, and use of energy. Whether the municipal energy plans have contributed to or preferably controlled the development of local energy systems is unclear. In the research project “Strategic Environmental Assessment of Local Energy Systems,” financed by the Swedish National Energy Administration, the municipal energy plan as a tool for controlling energy use and the efficiency of the local energy system is studied. In an introductory study, twelve municipal energy plans for the county of Östergötland in southern Sweden have been analyzed. This paper presents and discusses results and conclusions regarding municipal strategies for energy efficiency based on the introductory study. Introduction Energy Efficiency and Swedish Municipalities Opportunities for improving the efficiency of Swedish energy systems have been emphasized in several reports such as a recent study made for the Swedish government (SOU 2001). Although work for effective energy use has been carried out in Sweden for 30 years, the calculated remaining potential for energy savings is still high. However, there have been changes in the energy system. For example, industry has slightly increased the total energy use, but their use of oil has been reduced by two-thirds since 1970. Meanwhile, the production in the industry has increased by almost 50%. This means that energy efficiency in the industry is much higher today than in the 1970s (Table 1). -

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

The Linköping Mitre Ecclesiastical Textiles and Episcopal Identity

CHAPTER 9 THE LINKÖPING MITRE ECCLESIASTICAL TEXTILES AND EPISCOPAL IDENTITY Ingrid Lunnan Nødseth Questions of agency have been widely discussed in art history studies in recent decades, with scholars such as Alfred Gell and W. T. Mitchell arguing that works of art possess the qualities or powers of living beings. Recent scholar ship has questioned whether Max Weber’s notion of charisma as a personal quality can be extended to the realm of things such as charismatic objects or charismatic art. Textiles are particularly interesting in this regard, as clothing transforms and extends the corporal body acting as a ‘social skin’, this prob lematizes the human/object divide. As such, ecclesiastical dress could be con sidered part of the priest’s social body, his identity. The mitre was especially symbolic and powerful as it distinguished the bishop from the lower ranks of the clergy. This article examines the richly decorated Linköping mitre, also known as Kettil Karlsson’s mitre as it was most likely made for this young and ambitious bishop in the 1460s. I argue that the aesthetics and rhetoric of the Linköping mitre created charismatic effects that could have contributed to the charisma of Kettil Karlsson as a religious and political leader. This argument, however, centers not so much on charismatic objects as on the relationship between personal charisma and cultural objects closely identified with char ismatic authority. The Swedish rhyme chronicle Cronice Swecie describes [In Linköping I laid down my episcopal vestments how bishop Kettil Karlsson in 1463 stripped himself of and took up both shield and spear / And equipped his episcopal vestments (biscopsskrud) in the cathedral myself as a warrior who can break lances in combat.] of Linköping, only to dress for war with shield and spear (skiöll och spiwt) like any man who could fight well with This public and rhetorical event transformed the young a lance in combat: bishop from a man of prayer into the leader of a major army. -

6/17/2021 Page 1 Powered by Territorial Extension of Municipality

9/26/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links SVEZIA / Östra Mellansverige / Province of Östergötlands län / Vadstena Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH SVEZIA Municipalities Åtvidaberg Stroll up beside >> Mjölby Boxholm Motala Finspång Norrköping Kinda Ödeshög Linköping Söderköping Vadstena Valdemarsvik Ydre Provinces ÖREBRO LÄN SÖDERMANLANDS LÄN ÖSTERGÖTLANDS LÄN UPPSALA LÄN VÄSTMANLANDS LÄN Regions Powered by Page 2 Mellersta Övre Norrland L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Norrland Adminstat logo Småland med DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Norra SVEZIAöarna Mellansverige Stockholm Östra Sydsverige Mellansverige Västsverige Municipality of Vadstena Territorial extension of Municipality of VADSTENA and related population density, population per gender and number of households, average age and incidence of foreigners TERRITORY DEMOGRAPHIC DATA (YEAR 2019) Östra Region Mellansverige Inhabitants (N.) 7,428 Östergötlands Province län Families (N.) 3,735 Östergötlands Males (%) 49.8 Sign Province län Females (%) 50.2 Hamlet of the 0 Foreigners (%) 4.4 municipality Average age 47.9 Surface (Km2) 412.19 (years) Population density 18.0 Average annual (Inhabitants/Kmq) variation +0.07 (2015/2019) MALES, FEMALES AND DEMOGRAPHIC BALANCE FOREIGNERS INCIDENCE (YEAR 2019) (YEAR 2019) Powered by Page 3 ^L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH SVEZIA Balance of nature [1], Migrat. balance [2] Balance of nature = Births - Deaths ^ Migration balance = Registered - Deleted Rankings Municipality of vadstena is on 44° place among 52 municipalities in region by demographic size is on 268° place among 312 municipalities in SWEDEN by demographic size is on 9° place among 312 municipalities in SWEDEN per average age Fractions Address Contacts Svezia AdminStat 41124 Via M. -

88 Foundation of the Pirita Convent, 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources

88 Ruth Rajamaa Foundation of the Pirita Convent, known to researchers of the Birgittine Order 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources but, together with other Swedish sources, it Ruth Rajamaa is possible to discover new aspects in the Summary relations between the Pirita and Vadstena convents. Abstract: This article is largely based on Vadstena was the mother abbey of the Order Swedish sources and examines the role of of the Holy Saviour, Ordo Sancti Salvatoris. the Vadstena abbey in the history of the The founder, Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303 Pirita convent, from the founding of its 1373), had a revelation in 1346: Christ gave daughter convent in 1407 until the conse- her the constitution of a new order. In 1349, cration of the independent convent in 1431. Birgitta left Sweden and settled in Rome in Various aspects of the Vadstena abbey’s order to personally ask permission from the patronage are pointed out, revealing both pope to found a new order. The Order of the a helpful attitude and interfering guid- Holy Saviour was confirmed in 1370 and ance. Vadstena paid more attention to again in 1378 under the Augustinian Rule, Pirita than to other Birgittine monasteries with the addition of the Rule of the Holy and had many brothers and sisters of its Saviour, Ordo sancti Augustini sancti Sal- monastery there. Such closeness to the vatoris nuncupatus. mother monastery is a totally new pheno- The main aim of the Birgittine Order was menon in the history of researching Pirita, to purify all Christians; it was established and still needs more thorough analysis. -

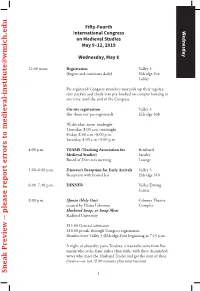

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology

Institutionen för fysik kemi och biologi Examensarbete 16 hp Recycling potential of phosphorus in food – a substance flow analysis of municipalities ERIKA WEDDFELT LiTH-IFM-G-EX--12/2678--SE Handledare: Karin Tonderski, Linköpings universitet Examinator: Anders Hargeby, Linköpings universitet Institutionen för fysik, kemi och biologi Linköpings universitet 581 83 Linköping, Datum/Date Institutionen för fysik, kemi och biologi 2012-06-01 Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology Avdelningen för biologi Språk/Language Rapporttyp ISBN InstutitionenReport category för fysikLITH -ochIFM -Gmätteknik-EX—12/2678 —SE Engelska/English __________________________________________________ Examensarbete ISRN __________________________________________________ Serietitel och serienummer ISSN Title of series, numbering Handledare/Supervisor Karin Tonderski URL för elektronisk version Ort/Location: Linköping http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu: diva-78998 Titel/Title: Recycling potential of phosphorus in food – a substance flow analysis of municipalities Författare/Author: Erika Weddfelt Sammanfattning/Abstract: In this study the opportunities to recycle the phosphorus contained in food handling were identified in four municipalities in the county of Östergötland. The aim was to map the flow and find out whether there were differences between municipalities with food processing industries generating large amounts of waste or phosphorus rich wastewater, or if there were differences between municipalities of different size. It was also investigated to what extent the agricultural demand of phosphorus could be covered by recycling of phosphorus from the food handling system. The result showed that between 27% and 73% of the phosphorus was found in the sludge from wastewater treatment, and that between 13% and 49% of the phosphorus was found in the centrally collected organic waste. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

Sustainable Birgitta Ways GP Sustainability Report Vadstena Case

Sustainable Birgitta Ways GP sustainability report Vadstena case Produced by: Emil Selse, Region Östergötland, Sweden December 2019 Sustainable Birgitta Ways – GR sustainability report Contents Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose of report .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Approach, Work undertaken ......................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Result ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Proposed next steps ...................................................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Green Pilgrimage Project ......................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Background .............................................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Content in this report ............................................................................................................. -

The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches

CM 2014 ombrukket3.qxp_CM 30.04.15 15.46 Side 114 The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches JONAS CARLQUIST This article discusses the use of wooden Marian sculptures in Swedish parish churches during the Middle Ages. By analysing the Marian sculptures’ context, design and mate- riality together with vernacular devotional literature, I suggest that these different media together collaborated in the education of the lay congregation about the life of the Virgin and her cult. Together, sculptures and prayers facilitated private meditation. I will use the Madonna of Knutby Church as my leading example. Introduction Located in the Swedish arch-diocese of Uppland, Knutby is a small parish with a 13th century, church situated close to Uppsala. The church’s patron is St Martin of Tours, but its interior also contains many images of the Virgin Mary. Among other objects, the church contains an Apocalyptic Madonna from the late 15th century (according to Swedish history Museum, Stockholm). During the late medieval period in Swe- den, namely in the 15th and 16th centuries, many examples of such Madonnas were locally produced for parish churches, and apocalyptic Madonnas were also imported into Sweden, usually from northern Germany or the netherlands (see for example Andersson 1980: 64–78). In this article, I will discuss the reasons behind the design, the intertextuality (i.e. the shaping of a text’s meaning by another text by for example allusion, quotation), and the congregation’s assumed perception of the Madonna of Knutby to provide a deeper understanding of the general use of wooden Marian sculptures in medieval Sweden. -

Health Indicators for Swedish Children

HEALTH INDICATORS FOR SWEDISH CHILDREN by Lennart Köhler A CONTRIBUTION TO A MUNICIPAL INDEX Save the Children fights for children’s rights. We influence public opinion and support children at risk in Sweden and in the world. Our vision is a world in which all children's rights are fulfilled • a world which respects and values each child • a world where all children participate and have influence • a world where all children have hope and opportunity Save the Children publishes books and reports in order to spread knowledge about the conditions under which children live, to give guidance and to inspire new thought. and discussion. Our publications can be ordered through direct contact with Save the Children or via Internet at www.rb.se/bokhandel © 2006 Save the Children and the author ISBN 10: 91-7321-214-8 ISBN 13: 978-91-7321-214-4 Code no 3332 Author: Lennart Köhler Translation: Janet Vesterlund Technical language edition: Keith Barnard Production Manager, layout: Ulla Ståhl Cover: Annelie Rehnström Printed in Sweden by: Elanders Infologistics Väst AB Save the Children Sweden SE-107 88 Stockholm Visiting address: Landsvägen 39, Sundbyberg Telephone +46 8 698 90 00 Fax +46 8 698 90 10 [email protected] www.rb.se Contents Foreword 5 Background 6 1. Measuring and evaluating the health of a population 6 2. Special conditions in measuring the health of children and adolescents 11 3. Some features of the development of children’s health and wellbeing in Sweden 14 4. Swedish municipalities and their role in children’s health 23 Indicators of children’s health 27 5. -

Diarium Vadstenense: a Late Medieval Memorial Book and Political Chronicle

Diarium Vadstenense: A Late Medieval Memorial Book and Political Chronicle Claes Gejrot The National Archives of Sweden, Stockholm This article deals with the Diarium Vadstenense, a Liber memorialis originating in Vadstena, the abbey founded by Saint Birgitta of Sweden. Written by a succession of Birgittine friars, this parchment manuscript is still preserved in its original form. It records internal, monastic events from the founding of the abbey in the second half of the fourteenth century to the time the last brother left the community, after the Reformation. Glimpses from the world outside the abbey are seen here and there throughout the text. However, during a central part of the fifteenth century, some of the entries were extended, and the writing changes character. These texts can be seen as a more or less continuous chronicle, tendentiously describing the complicated political situation in Sweden in the 1460s, a time marked by wars and conflicts. Indeed, parts of the texts were so controversial that they were later (partly) erased by a cautious medieval ‘editor’. The focus in this article will be on the time frame when the text was written, the personal views and opinions of the writers, confidentiality, political bias and censorship. The Diarium Vadstenense1 – and especially the chronicle parts of its text – will be at the centre of our attention, but let us start from the beginning. Vadstena Abbey was founded by Saint Birgitta (1303– 1373) in the Swedish province of Östergötland and intended for sixty sisters and twenty-five brothers. Not long after the activities began in the abbey in the 1370s,2 a series of brothers began reporting on events inside the monastery and sometimes also on events outside.