Why Are Nuns Funny?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

'Tale of a Nun'

‘Tale of a nun’ Vertaald door: L. Housman en L. Simons bron L. Housman en L. Simons (vert.), ‘Tale of a nun’. In: The Pageant 1 (1896), p. 95-116 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_bea001tale01_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl 95 Tale of a nun * SMALL good cometh to me of making rhyme; so there be folk would have me give it up, and no longer harrow my mind therewith. But in virtue of her who hath been both mother and maiden, I have begun the tale of a fair miracle, which God without doubt hath made show in honour of her who fed him with her milk. Now I shall begin and tell the tale of a nun. May God help me to handle it well, and bring it to a good end, even so according to the truth as it was told me by Brother Giselbrecht, an ordained monk of the order of Saint William; he, a dying old man, had found it in his books. The nun of whom I begin my tale was courtly and fine in her bearing; not even nowadays, I am sure, could one find another to be compared to her in manner and way of kooks. That I should praise her body in each part, exposing her beauty, would become me not well; I will tell you, then, what office she used to hold for a long time in the cloister where she wore veil. Custodian she was there, and whether it were day or night, I can tell you she was neither lazy nor slothful. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

Culross Abbey

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC0 20 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13334) Taken into State care: 1913 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CULROSS ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CULROSS ABBEY SYNOPSIS The monument comprises the ruins of the former Cistercian abbey of St Mary and St Serf at Culross. It was founded in the 13th century by Malcolm, Earl of Fife, as a daughter-house of Kinloss. After the Protestant Reformation (1560), the east end of the monastic church became the parish church of Culross. The structures in care comprise the south wall of the nave, the cloister garth, the surviving southern half of the cloister's west range and the lower parts of the east and south ranges. The 17th-century manse now occupies the NW corner of the cloister, with the garth forming the manse’s garden. The east end of the abbey church is not in state care but continues in use as a parish church. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview: 6th century - tradition holds that Culross is the site of an early Christian community headed by St Serf, and of which St Kentigern was a member. -

The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 PDF Book

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT: TERROR AND FAITH IN 1605 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Antonia Fraser | 448 pages | 01 Feb 2003 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780753814017 | English | London, United Kingdom The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 PDF Book Before he died Tresham had also told of Garnet's involvement with the mission to Spain, but in his last hours he retracted some of these statements. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Thomas Wintour begged to be hanged for himself and his brother, so that his brother might be spared. Thomas Wintour and Littleton, on their way from Huddington to Holbeche House, were told by a messenger that Catesby had died. Details of the assassination attempt were allegedly known by the principal Jesuit of England, Father Henry Garnet. Synopsis About this title With a narrative that grips the reader like a detective story, Antonia Fraser brings the characters and events of the Gunpowder Plot to life. Seven of the prisoners were taken from the Tower to the Star Chamber by barge. As news of "John Johnson's" arrest spread among the plotters still in London, most fled northwest, along Watling Street. Seller Inventory aa2a43fc1e57f0bdf. At first glance, it might seem a little odd that I am reading a book so closely connected with November and Bonfire Night at the beginning of August. He also spoke of a Christian union and reiterated his desire to avoid religious persecution. Macbeth , Act 2 Scene 3. This is a complex story, with many players, both high and low, but Fraser lays it out clearly and concisely. -

Sacred Landscapes and the Early Medieval European Cloister

Sacred Landscape and the Early Medieval European Cloister. Unity, Paradise, and the Cosmic Mountain Author(s): Mary W. Helms Source: Anthropos, Bd. 97, H. 2. (2002), pp. 435-453 Published by: Anthropos Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40466044 . Accessed: 29/07/2013 13:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Anthropos Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropos. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 152.13.249.96 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:52:20 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions § ANTHROPOS 97.2002:435-453 r'jT! _ Sacred Landscape and the Early Medieval European Cloister Unity,Paradise, and theCosmic Mountain Mary W. Helms Abstract. - The architecturalformat of the early medieval Impressiveevidence of the lattermay be found monastery,a widespread feature of the Western European both in the structuralforms and iconograph- landscape,is examinedfrom a cosmologicalperspective which ical details of individual or argues thatthe garden,known as the garth,at the centerof buildings comp- the cloister reconstructedthe firstthree days of creational lexes dedicatedto spiritualpurposes and in dis- paradiseas describedin Genesis and, therefore,constituted the tributionsof a numberof such constructions symboliccenter of the cloistercomplex. -

Letters from Early Modern English Nuns in Exile

“NO OTHER MEANS THAN BY PEN”: LETTERS FROM EARLY MODERN ENGLISH NUNS IN EXILE by Tanyss Sharp, B.A. Honours A thEsis submittEd to thE Faculty of GraduatE and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillmEnt of thE requiremEnts for thE dEgreE of MastEr of Arts in History CarlEton UnivErsity Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Tanyss Sharp ii Abstract This thesis explores how early modern English nuns in exilE on the European continent purposEfully utilizEd lEttEr writing as a stratEgy of communication with the outside world. Cut off from their homEland and familiEs by both geographic distancE and physical Enclosure, lEttErs provided womEn religious with a mEdium to ensure their convents’ survival and presErve English Catholicism. This critical analysis of nuns’ lEttErs reveals the multidimEnsional nature and intEntional construction of their correspondencE. Nuns made deliberatE epistolary choicEs. They employed stratEgic language, utilizEd flattEry and humility, as wEll as exaggeration and gossip to achiEve their objEctives. A comparison of individual epistolary experiEncEs demonstratEs that lEttErs wEre vital for maintaining familial and kinship tiEs, financial and spiritual economiEs, political EngagemEnt, and the transnational diffusion of information. iii Acknowledgements This thesis could not have beEn complEtEd without the support and encouragemEnt of numErous peoplE. This thesis was funded in part by SSHRC and OGS, which made it significantly EasiEr to accomplish and allowEd for a vital resEarch trip. During my timE in England and Belgium the assistancE of thosE at the British Library, National Archives, BodlEian Library, Ushaw CollEge, Ghent StatE Archives, ArchdiocEsE of MEchelEn-BrussEls and Bisschoppelijk ArchiEf Bruges was invaluablE to my resEarch ExperiEncE. In particular, I would like to thank Abbot GEoffrey Scott of Douai Abbey for his timE and allowing me accEss to his archive. -

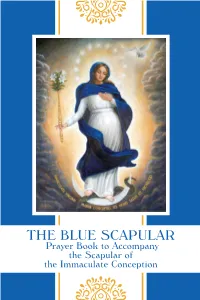

THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception

THE BLUE SCAPULAR THE BLUE THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception Blessed Virgin Mary Immaculately Conceived, commissioned by the Marian Fathers and pained by Francis Smuglewicz (1745-1807). In 1782, this painting was placed in St. Vitus Church in Rome. THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception Editors Janusz Kumala, MIC Andrew R. Mączyński, MIC Licheń Stary 2021 Copyright © 2021 Centrum Formacji Maryjnej “Salvatoris Mather,” Licheń Stary, 2021 All world rights reserved. For texts from the English Edition of the Diary of St. Maria Faustina Kowalska “Divine Mercy in My Soul,” Copyright © 1987 Congregation of Marians Written and edited with the collaboration of: Michael B. Callea, MIC Anthony Gramlich, MIC S. Seraphim Michalenko, MIC Konstanty Osiński Translated from Polish: Marina Batiuk, Ewa St. Jean Proofreaders: David Came, Richard Drabik, MIC, Christine Kruszyna Page design: Front cover: “Woman of the Apocalypse” – Most Blessed Virgin Mary, Immaculately Conceived. Painting by Janis Balabon, 2010. General House of the Marian Fathers in Rome, Italy. Imprimi potest Very Rev. Fr. Kazimierz Chwalek, MIC, Superior of the B.V.M., Mother of Mercy Province December 8, 2017 ISBN 978-1-59614-248-0 Published through the efforts of the General Promoter of the Marian Fathers’ Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception of the Most B.V.M. Fourth amended edition ......................................................................................................... was admitted to the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary which entitles him/her to share spiritually in the life, prayers, and good works of the Congregation of Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary and was vested in the Blue Scapular which grants him/her participation in plenary indulgences and special graces approved by the Holy See. -

Introduction

1 I n t r o d u c t i o n eligious sisters and nuns, known collectively as women religious,1 have always operated in a liminal place in church and popular R culture. Nuns for centuries maintained a spiritual capital that gave them a special role in the life of the Catholic Church. Th ough some individual abbesses may have wielded signifi cant power, women religious were never canonically members of the clergy. Th ey had, however, in popular understanding, a ‘higher calling’. 2 Th rough the institutions they managed, female religious had enormous infl uence in shaping generations of Catholics. Th ey were, by the nineteenth century, 1 Th e term religious life refers to a form of life where men or women take three vows, of poverty, chastity and obedience, and are members of a particular religious institute which is governed by a rule and constitution. Catholic religious life has traditionally been divided into two main categories: orders of contemplative nuns whose work is prayer of the Divine Offi ce inside the cloister and ‘active’ congregations of religious sisters whose ministry or apostolate (traditionally teaching, nursing and social welfare) is outside the cloister. Th e terms sisters and nuns were are oft en used interchangeably, although with the codifi cation of Canon Law in 1917 the term sister came to defi ne women who took simple vows and worked outside the cloister and the term nun came to refer to contemplatives who took solemn vows and lived a life of prayer behind cloister walls. Catholic religious sisters and nuns are oft en referred to collectively as women religious. -

Catholic Church 8500 N

SAINT HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 8500 N. Owasso Expressway Owasso, OK 74055 | (918) 272-3710 | sthenryowasso.org | August 30, 2020 Twenty-second Sunday in Ordinary Time 30 de Agosto, 2020 Vigésino-segundo domingo en Tiempo Ordinario Parish Information Información Parroquial Rev. Matt La Chance, Pastor [email protected] Rev. Bala Yaddanapalli, Associate Pastor ext.110 [email protected] Deacon Edmundo Martinez Deacon Larry Schneider Deacon Emeritus Vernon Foltz Deacon Emeritus Don LeMieux In the event of sacramental emergencies, call 918.609.6542. En caso de emergencias sacramentales, llame al 918.609.6542. Business Manager Denise Haffner [email protected] ext.100 Coordinator of Faith Formation Laura Valdez [email protected] ext. 105 Coordinator of Youth Ministry Katie Salamon [email protected] ext. 102 Faith Formation Secretary Kathy Hendricks [email protected] ext. 104 Coordinator of Ministries Sahira Bravo [email protected] ext. 107 FebruaryJulyAugustSeptember 29, 5,30, 2018 4, 2018 2020 24, 2018 2017 Seventeenth Eighteenth Fifth Twenty-fifth SundaySunday Sunday in in Sunday in Ordinary Ordinary Ordinary Twenty-second in Ordinary TimeTime Time Time Sunday in Ordinary Time Weekly Calendar Calendario Semanal Sun., Aug. 30 Mass Dom. 30, Ago. Misa Mon., Aug. 31 Daily Mass Lun. 31, Ago. Misa Diaria Tue., Sept. 1 Daily Mass Mar. 1°, Set. Misa Diaria Wed., Sept. 2 Daily Mass Mié. 2, Set. Misa Diaria Thu., Sept. 3 Daily Mass Jue. 3, Set. Misa Diaria Fri., Sept. 4 Daily Mass Vie. 4, Set. Misa Diaria Mass Misa Sat., Sept. 5 Sáb. 5, Set. Confession Confesiones Mass Intentions/Intenciones: Aug. 29—Sept. 4 / Del 29 de Ago. -

The Reformation

The Reformation Characters of the Reformation Hilaire Belloc In bold living colours Belloc sketches 23 famous men and women of the Reformation period, analysing their strengths, weaknesses, mistakes and motives and pinpointing deeds that changed the course of history. There are more than a few surprises here, as Belloc often puts the real responsibility for the Reformation on persons not usually appreciated by history. He describes the characters and deeds of real people, tracing the results of their greed, lust, tenacity, blindness, fear and - in the case of St Thomas More - heroic Catholic constancy. TAN 978 089555466 6 210 pages £7.99 How the Reformation Happened Hilaire Belloc Belloc provides a largely untold story that answers a critical historical question about Western civilization: How did Christendom come to suffer shipwreck in the Protestant Reformation? He admits that corruption among churchmen and clerical abuses in the use of church revenues prepared the way for the flood of revolt. But he uncovers other, more decisive, factors involved in the movement. He demonstrates that it was not doctrine, but rather avarice and rebellion against the clergy, that originally fuelled the Reformation. TAN 978 089555465 9 224 pages £7.99 Luther and His Progeny Edited by John C Rao 500 Years of Protestantism & Its Consequences for Church, State and Society A brilliant collection of essays examining Martin Luther's role in the dissolution of medieval Christendom and his influence on subsequent developments. Anyone who wants to understand the long decline from the Catholic Middle Ages to the secular present will find a wealth of insight in this book.