'Tale of a Nun'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

What They Wear the Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 in the Habit

SPECIAL SECTION FEBRUARY 2020 Inside Poor Clare Colettines ....... 2 Benedictines of Marmion Abbey What .............................. 4 Everyday Wear for Priests ......... 6 Priests’ Vestments ...... 8 Deacons’ Attire .......................... 10 Monsignors’ They Attire .............. 12 Bishops’ Attire ........................... 14 — Text and photos by Amanda Hudson, news editor; design by Sharon Boehlefeld, features editor Wear Learn the names of the everyday and liturgical attire worn by bishops, monsignors, priests, deacons and religious in the Rockford Diocese. And learn what each piece of clothing means in the lives of those who have given themselves to the service of God. What They Wear The Observer | FEBRUARY 2020 | 1 In the Habit Mother Habits Span Centuries Dominica Stein, PCC he wearing n The hood — of habits in humility; religious com- n The belt — purity; munities goes and Tback to the early 300s. n The scapular — The Armenian manual labor. monks founded by For women, a veil Eustatius in 318 was part of the habit, were the first to originating from the have their entire rite of consecrated community virgins as a bride of dress alike. Belt placement Christ. Using a veil was Having “the members an adaptation of the societal practice (dress) the same,” says where married women covered their Mother Dominica Stein, hair when in public. Poor Clare Colettines, “was a Putting on the habit was an symbol of unity. The wearing of outward sign of profession in a the habit was a symbol of leaving religious order. Early on, those the secular life to give oneself to joining an order were clothed in the God.” order’s habit almost immediately. -

Culross Abbey

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC0 20 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13334) Taken into State care: 1913 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE CULROSS ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH CULROSS ABBEY SYNOPSIS The monument comprises the ruins of the former Cistercian abbey of St Mary and St Serf at Culross. It was founded in the 13th century by Malcolm, Earl of Fife, as a daughter-house of Kinloss. After the Protestant Reformation (1560), the east end of the monastic church became the parish church of Culross. The structures in care comprise the south wall of the nave, the cloister garth, the surviving southern half of the cloister's west range and the lower parts of the east and south ranges. The 17th-century manse now occupies the NW corner of the cloister, with the garth forming the manse’s garden. The east end of the abbey church is not in state care but continues in use as a parish church. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview: 6th century - tradition holds that Culross is the site of an early Christian community headed by St Serf, and of which St Kentigern was a member. -

Sacred Landscapes and the Early Medieval European Cloister

Sacred Landscape and the Early Medieval European Cloister. Unity, Paradise, and the Cosmic Mountain Author(s): Mary W. Helms Source: Anthropos, Bd. 97, H. 2. (2002), pp. 435-453 Published by: Anthropos Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40466044 . Accessed: 29/07/2013 13:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Anthropos Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Anthropos. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 152.13.249.96 on Mon, 29 Jul 2013 13:52:20 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions § ANTHROPOS 97.2002:435-453 r'jT! _ Sacred Landscape and the Early Medieval European Cloister Unity,Paradise, and theCosmic Mountain Mary W. Helms Abstract. - The architecturalformat of the early medieval Impressiveevidence of the lattermay be found monastery,a widespread feature of the Western European both in the structuralforms and iconograph- landscape,is examinedfrom a cosmologicalperspective which ical details of individual or argues thatthe garden,known as the garth,at the centerof buildings comp- the cloister reconstructedthe firstthree days of creational lexes dedicatedto spiritualpurposes and in dis- paradiseas describedin Genesis and, therefore,constituted the tributionsof a numberof such constructions symboliccenter of the cloistercomplex. -

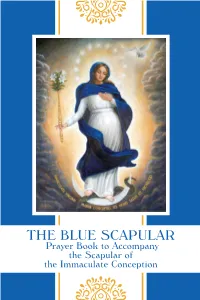

THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception

THE BLUE SCAPULAR THE BLUE THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception Blessed Virgin Mary Immaculately Conceived, commissioned by the Marian Fathers and pained by Francis Smuglewicz (1745-1807). In 1782, this painting was placed in St. Vitus Church in Rome. THE BLUE SCAPULAR Prayer Book to Accompany the Scapular of the Immaculate Conception Editors Janusz Kumala, MIC Andrew R. Mączyński, MIC Licheń Stary 2021 Copyright © 2021 Centrum Formacji Maryjnej “Salvatoris Mather,” Licheń Stary, 2021 All world rights reserved. For texts from the English Edition of the Diary of St. Maria Faustina Kowalska “Divine Mercy in My Soul,” Copyright © 1987 Congregation of Marians Written and edited with the collaboration of: Michael B. Callea, MIC Anthony Gramlich, MIC S. Seraphim Michalenko, MIC Konstanty Osiński Translated from Polish: Marina Batiuk, Ewa St. Jean Proofreaders: David Came, Richard Drabik, MIC, Christine Kruszyna Page design: Front cover: “Woman of the Apocalypse” – Most Blessed Virgin Mary, Immaculately Conceived. Painting by Janis Balabon, 2010. General House of the Marian Fathers in Rome, Italy. Imprimi potest Very Rev. Fr. Kazimierz Chwalek, MIC, Superior of the B.V.M., Mother of Mercy Province December 8, 2017 ISBN 978-1-59614-248-0 Published through the efforts of the General Promoter of the Marian Fathers’ Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception of the Most B.V.M. Fourth amended edition ......................................................................................................... was admitted to the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary which entitles him/her to share spiritually in the life, prayers, and good works of the Congregation of Marian Fathers of the Immaculate Conception of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary and was vested in the Blue Scapular which grants him/her participation in plenary indulgences and special graces approved by the Holy See. -

Meeting of Pope Francis with the Superiors General

Vincentiana, January-March 2014 Meeting of Pope Francis with the Superiors General Vatican Press Offi ce The Union of Superiors General held its 82nd General Assembly in the Salesianum in Rome from November 27-29, 2013. The story of three experiences provided the basis for refl ections and encounters of the various linguistic groups. Fr. Janson Hervé of the Little Brothers of Jesus spoke of “the light that helps me be at the service of my brothers and how Pope Francis strengthens my hope”. Br. Mauro Jöhri, Capu- chin, explained “how Pope Francis is an inspiration to me and a chal- lenge for the offi ce I hold within my Order” Finally, Fr. Hainz Kulüke, of the Society of the Divine Word, spoke about “leadership within a religious missionary congregation against the background of an international and inter-cultural context following the example of Pope Francis”. The Holy Father chose to meet with the Superiors in the Vatican for three hours, rather than the short encounter normally foreseen: no address was prepared in advance, but instead a long, informal and fraternal discussion took place, composed of questions and answers. Various aspects and problems of the religious life were tackled. The Pope often interspersed his speech with personal stories taken from his pastoral experience. The fi rst set of questions related to the identity and mission of consecrated life. What kind of consecrated life do we expect today? One which offers a special witness was the answer. “You must truly be witnesses of a different way of doing and being. You must embody the values of the Kingdom”. -

Read the Rule of Saint Benedict

The Rule of St. Benedict 1 The Rule of Saint Benedict (Translated into English. A Pax Book, preface by W.K. Lowther Clarke. London: S.P.C.K., 1931) PROLOGUE Hearken continually within thine heart, O son, giving attentive ear to the precepts of thy master. Understand with willing mind and effectually fulfil thy holy father’s admonition; that thou mayest return, by the labour of obedience, to Him from Whom, by the idleness of disobedience, thou hadst withdrawn. To this end I now address a word of exhortation to thee, whosoever thou art, who, renouncing thine own will and taking up the bright and all-conquering weapons of obedience, dost enter upon the service of thy true king, Christ the Lord. In the first place, then, when thou dost begin any good thing that is to be done, with most insistent prayer beg that it may be carried through by Him to its conclusion; so that He Who already deigns to count us among the number of His children may not at any time be made aggrieved by evil acts on our part. For in such wise is obedience due to Him, on every occasion, by reason of the good He works in us; so that not only may He never, as an irate father, disinherit us His children, but also may never, as a dread-inspiring master made angry by our misdeeds, deliver us over to perpetual punishment as most wicked slaves who would not follow Him to glory. Let us therefore now at length rise up as the Scripture incites us when it says: “Now is the hour for us to arise from sleep.” And with our eyes open to the divine light, let us with astonished ears listen to the admonition of God’s voice daily crying out and saying: “Today if ye will hear His voice, harden not your hearts.” And again: “He who has the hearing ear, let him hear what the Spirit announces to the churches.” And what does the Spirit say? “Come, children, listen to me: I will teach you the fear of the Lord. -

Cloister Gardens, Courtyards and Monastic Enclosures

CLOISTER GARDENS, COURTYARDS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES 1 Editor Ana Duarte Rodrigues Authors Ana Duarte Rodrigues Antonio Perla de las Parras João Puga Alves Luís Ferro Luísa Arruda Magdalena Merlos Teresa de Campos Coelho Victoria Soto Caba Design| Conception| Layout Maggy Victory Front cover photograph by Luís Ferro Published by Centro de História da Arte e Investigação Artística da Universidade de Évora and Centro Interuniversitário de História das Ciências e da Tecnologia ISBN: 978-989-99083-7-6 2 CLOISTER GARDENS, COURTYARDS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES Ana Duarte Rodrigues Coordination CHAIA/CIUHCT 2015 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE by Ana Duarte Rodrigues, 7 PART I – CLOISTERS BETWEEN CONTEMPLATIVE AND ACTIVE LIFE Ana Duarte Rodrigues Beyond contemplation, the real functions held at the cloisters, 13 Luís Ferro The Carthusian Hermitage Space. Santa Maria Scala Coeli’s cloister architecture, 37 João Puga Alves The Convent of Espírito Santo. A new approach to the study and dissemination of the convent spaces, 55 PART II – CLOISTERS AND COURTYARDS: FUNCTIONS AND FORMS Antonio Perla de las Parras and Victoria Soto Caba The Jardines de crucero: a possible study scenario for the gardens of Toledo, 77 Magdalena Merlos Variations around one constant: The cloister typology in the cultural landscape of Aranjuez, 97 PART III – CLOISTER GARDENS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES Teresa de Campos Coelho The Convent of St. Paul of Serra de Ossa: the integration in the landscape and Nature’s presence in its primitive gardens, 121 Luísa Arruda The Convent of Saint Paul at Serra de Ossa (Ossa Mountains). Baroque Gardens, 137 5 6 PREFACE by Ana Duarte Rodrigues We often share a feeling of quietness when strolling through cloisters, sometimes contemplating their puzzling image of both glory and decay, sometimes enjoying the perfume and the colors of their garden, listening to the mumbling water, or trying to decipher the tombstones’ inscriptions on the pavement beneath our feet. -

Cloister Gardens, Courtyards and Monastic Enclosures

CLOISTER GARDENS, COURTYARDS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES 1 Editor Ana Duarte Rodrigues Authors Ana Duarte Rodrigues Antonio Perla de las Parras João Puga Alves Luís Ferro Luísa Arruda Magdalena Merlos Teresa de Campos Coelho Victoria Soto Caba Design| Conception| Layout Maggy Victory Front cover photograph by Luís Ferro Published by Centro de História da Arte e Investigação Artística da Universidade de Évora and Centro Interuniversitário de História das Ciências e da Tecnologia ISBN: 978-989-99083-7-6 2 CLOISTER GARDENS, COURTYARDS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES Ana Duarte Rodrigues Coordination CHAIA/CIUHCT 2015 3 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE by Ana Duarte Rodrigues, 7 PART I – CLOISTERS BETWEEN CONTEMPLATIVE AND ACTIVE LIFE Ana Duarte Rodrigues Beyond contemplation, the real functions held at the cloisters, 13 Luís Ferro The Carthusian Hermitage Space. Santa Maria Scala Coeli’s cloister architecture, 37 João Puga Alves The Convent of Espírito Santo. A new approach to the study and dissemination of the convent spaces, 55 PART II – CLOISTERS AND COURTYARDS: FUNCTIONS AND FORMS Antonio Perla de las Parras and Victoria Soto Caba The Jardines de crucero: a possible study scenario for the gardens of Toledo, 77 Magdalena Merlos Variations around one constant: The cloister typology in the cultural landscape of Aranjuez, 97 PART III – CLOISTER GARDENS AND MONASTIC ENCLOSURES Teresa de Campos Coelho The Convent of St. Paul of Serra de Ossa: the integration in the landscape and Nature’s presence in its primitive gardens, 121 Luísa Arruda The Convent of Saint Paul at Serra de Ossa (Ossa Mountains). Baroque Gardens, 137 5 6 PREFACE by Ana Duarte Rodrigues We often share a feeling of quietness when strolling through cloisters, sometimes contemplating their puzzling image of both glory and decay, sometimes enjoying the perfume and the colors of their garden, listening to the mumbling water, or trying to decipher the tombstones’ inscriptions on the pavement beneath our feet. -

Florentine Convent As Practiced Place: Cosimo De'medici, Fra Angelico

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Art History Faculty Publications Art 2012 Florentine Convent as Practiced Place: Cosimo de’Medici, Fra Angelico, and the Public Library of San Marco Allie Terry-Fritsch Bowling Green State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/art_hist_pub Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Repository Citation Terry-Fritsch, Allie, "Florentine Convent as Practiced Place: Cosimo de’Medici, Fra Angelico, and the Public Library of San Marco" (2012). Art History Faculty Publications. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/art_hist_pub/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Medieval Jewish, Christian and Muslim Culture Encounters in Confluence and Dialogue Medieval Encounters 18 (2012) 230-271 brill.com/me Florentine Convent as Practiced Place: Cosimo de’Medici, Fra Angelico, and the Public Library of San Marco Allie Terry-Fritsch* Department of Art History, 1000 Fine Art Center, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403, USA *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract By approaching the Observant Dominican convent of San Marco in Florence as a “prac- ticed place,” this article considers the secular users of the convent’s library as mobile specta- tors that necessarily navigated the cloister and dormitory and, in so doing, recovers, for the first time, their embodied experience of the architectural pathway and the frescoed decora- tion along the way. To begin this process, the article rediscovers the original “public” for the library at San Marco and reconstructs the pathway through the convent that this secu- lar audience once used. -

The Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 1 Fall 1984 The Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity Miguel P. Flores C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Flores, Miguel P. C.M. (1984) "The Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 5 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol5/iss2/1 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The Superior General of the Congregation of Mission and of the Daughters of Charity Miguel Perez Flores, C.M. Translated by Francis Germovnik, C.M.* In this work I intend to study the figure of the Superior General of the Congregation of the Mission from the historicojuridical perspective. I exclude from my purpose the whole range of spiritual, apostolic, and juridical relationships, nor the fact that one and the same person is Communities. The Congregation of the Mission and the Daughters of Charity were, and continue to be, fully autonomous and independent from each other in their government. Neither the spiritual, apostolic, and juridical relationships, nor the fact that one and the same person is the Superior General of both Communities, nor the offices of the Director General and the Provincial Directors which are being discharged by the Priests of the Mission, have affected this autonomy and independence from the juridical point of view. -

From the Holy Land to the Cloister: the Decline of Female Ascetic Pilgrimages in the Early Medieval West (C

From the Holy Land to the Cloister: The Decline of Female Ascetic Pilgrimages in the Early Medieval West (c. 350-615) Manon Claire Williams Department of History University of Colorado at Boulder Primary Thesis Advisor Dr. Scott Bruce, Department of History Honors Council Representative Dr. Fred Anderson, Department of History Outside Reader Dr. Andrew Cain, Department of Classics Defense: April 2nd 2015 Abstract This paper will focus on the mobility of ascetic women from late antiquity through to the early Middle Ages with a particular emphasis on the practice of pilgrimage. As seen in multiple primary source documents, religious women from the West were journeying to the Holy Land and beyond from the fourth through to the early fifth centuries. This practice, however, is mentioned remarkably less in accounts of religious women north of the Alps in the late fifth century onwards. Evidence of women undertaking pilgrimages to the Holy Land is sparse while their male counterparts continued to make such journeys. Although the monastic rules that cloistered women certainly did have an impact on the movement of religious women in the early medieval West as other scholars have argued, there are a variety of external and non-religious factors that also contributed to the decline of female ascetic pilgrimages. This thesis will aim to give a more complete answer to this decline by focusing on the functions that religious women played in their communities, which effectively bound them to those same communities. Due to a lack of source material, the main focus of the early medieval period will be in Gaul, which will provide a case study for understanding the roles that religious women played in society within the context of early Merovingian politics and economy.