Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013

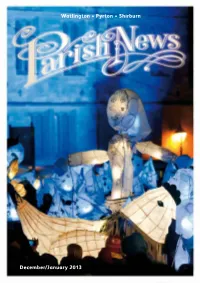

Watlington • Pyrton • Shirburn December/January 2013 1 CHRISTMAS WREATH MAKING WORKSHOPS B C J 2 Contents Dates for St.Leonards p.26-27 your diary Pyrton p.13 Advent Service of readings and Methodists p.14-15 music 4pm Sunday 2nd December Church services p.6-7 Christmas childrens services p.28 News from Registers p.33 Christmas Carol Services p.29 Ministry Team p.5 4 All Services p.19 Watlington Christmas Fair 1st Dec p.18 Christmas Tree Festival 8th-23rd December p.56 From the Editor A note about our Cover Page - Our grateful thanks to Emily Cooling for allowing us to use a photo of one of her extraordinary and enchanting Lanterns featured in the Local schools and community groups’ magical Oxford Lantern Parade. We look forward to writing more about Emily, a professional Shirburn artist; her creative children’s workshops and much more – Her website is: www.kidsarts.co.uk THE EDITORIAL TEAM WISH ALL OUR READERS A PEACEFUL CHRISTMAS AND A HEALTHY AND HAPPY NEW YEAR Editorial Team Date for copy- Feb/March 2013 edition is 8th January 2013 Editor…Pauline Verbe [email protected] 01491 614350 Sub Editor...Ozanna Duffy [email protected] 01491 612859 St.Leonard’s Church News [email protected] 01491 614543 Val Kearney Advertising Manager [email protected] 01491 614989 Helen Wiedemann Front Cover Designer www.aplusbstudio.com Benji Wiedemann Printer Simon Williams [email protected] 07919 891121 3 The Minister Writes “It’s the lights that get me in the end. The candlelight bouncing off the oh-so-carefully polished glasses on the table; the dim amber glow from the oven that silhouettes the golden skin of the roasting bird; the shimmering string of lanterns I weave through the branches of the tree. -

The Berkshire Echo 52

The Berkshire Echo Issue 52 l The Grand Tour: “gap” travel in the 18th century l Wartime harvest holidays l ‘A strange enchanted land’: fl ying to Paris, 1935 l New to the Archives From the Editor From the Editor It is at this time of year that my sole Holidays remain a status symbol Dates for Your Diary focus turns to my summer holidays. I in terms of destination and invest in a somewhat groundless belief accommodation. The modern Grand Heritage Open Day that time spent in a different location Tour involves long haul instead This year’s Heritage Open Day is Saturday will somehow set me up for the year of carriages, the lodging houses 11 September, and as in previous years, ahead. I am confi dent that this feeling and pensions replaced by fi ve-star the Record Offi ce will be running behind will continue to return every summer, exclusivity. Yet our holidays also remain the scenes tours between 11 a.m. and 1 and I intend to do nothing to prevent it a fascinating insight into how we choose p.m. Please ring 0118 9375132 or e-mail doing so. or chose to spend our precious leisure [email protected] to book a place. time. Whether you lie fl at out on the July and August are culturally embedded beach or make straight for cultural Broadmoor Revealed these days as the time when everyone centres says a lot about you. Senior Archivist Mark Stevens will be who can take a break, does so. But in giving a session on Victorian Broadmoor celebrating holidays inside this Echo, it So it is true for our ancestors. -

St Peter's Conservation Area Appraisal

St Peters Conservation Area Conservation Area Appraisal November 2018 To the memory of Liz Killick, who was instrumental to achieving this appraisal St Peter’s Conservation Area Appraisal Foreword by Councillor Tony Page, Lead Councillor for Strategic Environment Planning and Transport and Heritage Champion for Reading Borough Council. Reading is a town of many contrasts. It enjoys an excellent reputation as the capital and economic centre of the Thames Valley. However, Reading also has a rich historic heritage going back over 900 years and these aspects sit side by side in the vibrant town we enjoy today. To be able to respect our historic past while providing for an exciting future for the town is a particular challenge that Reading Borough Council intends to meet. The work undertaken to re- open the Abbey Ruins in 2018, within the new Abbey Quarter, is indicative of the Council’s promise to respect and enhance our historic past for the future. Reading’s valuable history has led to the designation of 15 Conservation Areas within the Borough, all supported by written Conservation Appraisals. Many of those appraisals are now relatively old and in need of review. Reading Borough Council is very grateful that various local communities, who have the intimate knowledge and understanding of their areas and local history, have initiated the process of reviewing our Conservation Area Appraisals. The Review of the St Peter’s Conservation Area Appraisal is the first appraisal to be formally reviewed under this new community led arrangement. The review has been underpinned by the knowledge, research, hard work and enthusiasm of volunteer members of Reading’s Conservation Area Advisory Committee and a number of interested local individuals. -

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY's Farmers-Continued

260 FAR BERKSHIRE. [KELLY'S FARMERs-continued. Bennett William, Head's farm, Cheddle- Brown C. Curridge, Chieveley,Newbury Adams Charles William, Red house, worth, Wantage Brown Francis P. Compton, Newbury Cumnor (Oxford) Benning Hy.Ashridge farm,Wokingh'm Brown John, Clapton farm, Kintbury, Adams George, PidnelI farm, Faringdon Benning- Mark, King's frm. Wokingham Hungerford Adams Richard, Grange farm, Shaw, Besley Lawrence,EastHendred,Wantage Brown John, Radley, Abingdon Newbury Betteridge Henry,EastHanney,Wantage Brown John, ""'est Lockinge, Wantage Adey George, Broad common, Broad Betteridge J.H.Hill fm.Steventon RS.O Brown Stephen, Great Fawley,Wantage Hinton, Twyford R.S.O Betteridge Richard Hopkins, Milton hill, Brown Wm.BroadHinton,TwyfordR.S.0 Adnams James, Cold Ash farm, Cold Milton, Steventon RS.O Brown W. Green fm.Compton, Newbury Ash, Newbury Betteridge Richard H. Steventon RS.O Buckeridge David, Inkpen, Hungerford Alden Robert Rhodes, Eastwick farm, Bettridge William, Place farm, Streat- Buckle Anthony, Lollingdon,CholseyS.O New Hinksey, Oxford ley, Reading Bucknell A.B. Middle fm. Ufton,Readng Alder Frederick, Childrey, Wantage Bew E. Middle farm, Eastbury,Swindon Budd Geo.Mousefield fm.Shaw,Newbury Aldridge Henry, De la Beche farm, Ald- Bew Henry, Eastbury, Swindon Bulkley Arthur, Canhurst farm, Knowl worth, Reading Billington F.W. Sweatman's fm.Cumnor hill, Twyford R.S.a Aldridge John, Shalbourn, Hungerford Binfield Thomas, Hinton farm, Broad Bullock George, Eaton, Abingdon Alexander Edward, Aldworth, Reading Hinton, -

Team Profile for the Appointment of a House for Duty Team Vicar to Serve the Villages of Ipsden and North Stoke Within the Langtree Team Ministry

TEAM PROFILE FOR THE APPOINTMENT OF A HOUSE FOR DUTY TEAM VICAR TO SERVE THE VILLAGES OF IPSDEN AND NORTH STOKE WITHIN THE LANGTREE TEAM MINISTRY The Appointment The Bishop of Dorchester and the Team Rector are seeking to appoint a Team Vicar to serve two of the rural parishes which make up the Langtree Team Ministry. The Langtree Team is in a large area of outstanding natural beauty and lies at the southern end of the Chilterns. It is in the Henley Deanery and the Dorchester Archdeaconry of the Diocese of Oxford. The villages lie in an ancient woodland area once known as Langtree, with Reading to the south (about 12 miles), Henley-on-Thames to the east (about 10 miles) and Wallingford to the northwest (about 3 miles). The Team was formed in 1981 with Checkendon, Stoke Row and Woodcote. In 1993 it was enlarged to include the parishes of Ipsden and North Stoke with Mongewell. The Team was further enlarged in 2003 to include the parish of Whitchurch and Whitchurch Hill. The combined electoral roll (2019) for our parishes was 308. The Team’s complete ministerial staff has the Team Rector serving Checkendon and Stoke Row, a stipendiary Team Vicar at Woodcote and non-stipendiary Team Vicars on a house- for-duty basis serving (a) Ipsden and North Stoke and (b) Whitchurch and Whitchurch Hill. There is a licensed Reader, a non-stipendiary Team Pastor and a part time Administrator. The Langtree Team staff provide support for the parishes in developing their response to local ministry needs. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside the Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold

Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Hillside The Crescent Padworth Berkshire RG7 5QS Price Guide: £460,000 Freehold A delightful extended semi detached family home with a garage and beautiful south west facing garden • Entrance hallway • Living room • Large fitted kitchen/dining room • 4 Bedrooms • Family bathroom • Garage • Driveway parking • Large rear garden • Double glazing • Oil fired central heating Location Padworth is 4 miles to the west of Junction 12 of the M4 at Theale and Reading and some 8 miles to the east of Newbury. It is a small village adjoining picturesque Aldermaston Wharf just to the south of the A4. It is ideally located for excellent communications being 7 miles west of Reading and the property is only a 10 minute walk from Aldermaston station. The surrounding countryside is particularly attractive and comprises Bucklebury Common and Chapel Row to the north (an area of outstanding natural beauty). The major towns of Reading and Newbury offer excellent local facilities. A lovely family home and garden ! Michael Simpson Description This lovely extended family home offers spacious and flexible accommodation arranged over two floors comprising an entrance hallway, cosy living room with open fire, a good size open plan fitted kitchen/dining room and cloakroom on the ground floor. On the first floor are four double bedrooms and the family bathroom. Other features include oil fired central heating and double glazing. Outside The front of the property is approached via the driveway which leads to the front door and garage. The rear garden has established flower bed borders offering a variety of lovely shrubs, plants and flowers. -

St Margaret's Church, Catmore Guidebook

st margaret’s church catmore, berkshire The Churches Conservation Trust LONDON Registered Charity No. 258612 PRICE: £1.00 The Churches Conservation st margaret’s church Trust welcomes you to catmore, berkshire st margaret’s church catmore, berkshire by ANDREW PIKE Many years ago Christians built and set apart this place for prayer. INTRODUCTION They made their church beautiful with their skill and craftsmanship. Here they The early inhabitants of Catmore must have enjoyed feline company since have met for worship, for children to be baptised, for couples to be married and the name means ‘a pool frequented by wild cats’. Catmore is mentioned in for the dead to be brought for burial. If you have time, enjoy the history, the Saxon charters from the 10th century and came into the possession of peace and the holiness here. Please use the prayer card and, if you like it, you Henry de Ferrers at the Norman Conquest. In 1266 the manor was granted are welcome to take a folded copy with you. to the Earl of Lancaster and so passed to the Crown on the accession of Although services are no longer regularly held here, this church remains Henry IV. The Eystons are first recorded as lords of the manor of Catmore consecrated; inspiring, teaching and ministering through its beauty and atmos - in 1433; they were also lords of the manor of Arches in nearby East Hendred. phere. It is one of more than 325 churches throughout England cared for by The Eyston family still owns both manors. The size of the church and churchyard suggests that the village was never The Churches Conservation Trust. -

Oxfordshire. South Stoke

DIRECTORY. J OXFORDSHIRE. SOUTH STOKE. 327 ()oombes M.A. of St. John'a College~ ·Cambridge, who 8 34 acres of land and 'Ig nf water;' nteab11'J "\Talue. resides at Ipsden. Dodd's charitr of £5 yearly was left £1,446; the population in I9II was x6g. b7 Thomas Dodd, in the year 1797, and is annually distributed in bread on Old Christmas Day. The prin- Post & T. Office.-Miss Martha Higgs, sub-postmistress. cipallandowners are John Wormald esq. J.P. of Springs, Letters arrive through Wallingford at 6.50 a.m. &; and Alexander Caspar Fraser esq. J.P., D.L. of Mange_- r.20 p.m.; dispatched at 10·4° a.m. & 1.40 & 7.20 "\\ell Park, who is lord of the manor; Messrs. John p.m. Crowm~ush is the nearest money order office .Fittman King and Robert Keen are also landowners. Council (Mongewell) School (mixed), erected in 1902, The 11oil is loamy; subsoil, chalk and gravel. The for 64 children; average attendance, 5 I; F'rancis W. oehief crops are wheat, oats and barley. The area is Russell, master PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Wormald John J.P. Springs; & 25' Higgs Martha ("Miss),grocer,& post off .Adams Harold William, The Grange Palace gate, London W \Keen Charles George, farmer,. North llateson James Edwin, Brook lodge Wyand Saml. Thos. Prospect lodge Stoke farm .Dodd Waiter J. H . King Jn.Pittman,farmer, :Rectory frm .Hartley Harold Thomas, Brook house COMMERCIAL. i Sin den John Thomas, gardener to J. Keen Robert Anderson Charles, bailiff to J. Wor- Wormald esq. J.P. Lake cottage Winslow Waiter, Mill house mald esq. -

Remembering the Men of Buckland St Mary Who Fought in WWI

Buckland St Mary Mary Buckland St who fought in WWI Remembering the men of Vanished Lives Vanished VANISHED LIVES ROSANNA BARTON BUCKLAND ST MARY PARISH COUNCIL Futility In Memory Of The Brave Men Move him into the sun— Gently its touch awoke him once, Of Buckland St Mary At home, whispering of fields half-sown. Who Gave Their Lives Always it woke him, even in France, In The Great War Until this morning and this snow. 1914-1919 If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds— Woke once the clays of a cold star. Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir? Was it for this the clay grew tall? —O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth’s sleep at all? Wilfred Owen Base of the War Memorial in Buckland St Mary churchyard ‘From Buckland St Mary there went into HM’s forces about seventy men from a population of about 450. Of these sixteen joined voluntarily all the remainder, except those underage at the time attested under Lord Derby’s scheme …1 … On the outbreak of war several ladies of the village took a course of sick nursing and ambulance work and being thus qualified they did most useful work at the V.A.D.2 hospital at Ilminster. The women of the parish were organised by Mesdames Lance and Pott and met weekly for the purpose of making pillowcases and moss bags for splints, several hundred of which, were sent to a collection station.’ (The Western Gazette) 1 See page 7. -

Medieval Occupation at the Rectory, Church Road

79 MEDIEVAL OCCUPATION AT THE RECTORY, CHURCH ROAD, CAVERSHAM, READING JAMES MCNICOLL-NORBURY AND DANIELLE MILBANK WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY STEVE FORD AND PAUL BLINKHORN SUMMARY A small area excavation took place at The Rectory, Church Road, Caversham, prior to redevelopment. It revealed features of medieval and later date. These comprised a small group of pits and parallel linear features, one of which was replaced by a flint-built wall. These are thought to be successive boundaries for properties fronting Church Road and add modestly to our knowledge of the topography of medieval and early post-medieval Caversham. A single struck flint of Mesolithic or earlier Neolithic date and three sherds of Bronze Age pottery were also found. Previous phases of investigation on the site had encountered only 19th- and 20th-century (or undated) features, but residual finds of medieval pottery and further prehistoric flints add to the evidence from the more recent work. INTRODUCTION of the chapel is not known, but it may have stood in The Rectory, Church Road, Caversham (Grade II this general area. Caversham Court (the Old Rectory) Listed) was built in 1823 and the Simonds family stood within the modern park. employed A. Pugin to remodel the house and gardens in the 1840s. In 1904, the (new) Rectory gained the The Notley lands passed to Christchurch College, land between that building and the boundary wall to Oxford. The extent of the late 16th century estate was described in Chancery proceedings: “The mansion or Caversham Court, together with more land behind the Rectory down to the River Thames. -

The Local Government Boundary Commission for England Electoral Review of West Berkshire

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF WEST BERKSHIRE Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of West Berkshire January 2018 Sheet 1 of 1 Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey WEST on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. ILSLEY CP Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2017. FARNBOROUGH CP KEY TO PARISH WARDS EAST COLD ASH CP ILSLEY CP FAWLEY STREATLEY A COLD ASH CP CATMORE CP CP B FLORENCE GARDENS C LITTLE COPSE ALDWORTH D MANOR PARK & MANOR FIELDS CP BRIGHTWALTON COMPTON CP CP GREENHAM CP LAMBOURN E COMMON F SANDLEFORD LAMBOURN CP DOWNLANDS NEWBURY CP CHADDLEWORTH BASILDON CP BEEDON G CLAY HILL CP RIDGEWAY H EAST FIELDS BASILDON I SPEENHAMLAND PEASEMORE CP J WASH COMMON CP K WEST FIELDS EAST GARSTON CP THATCHAM CP L CENTRAL PURLEY ON HAMPSTEAD ASHAMPSTEAD M CROOKHAM NORREYS CP THAMES CP LECKHAMPSTEAD CP N NORTH EAST CP O WEST TILEHURST PANGBOURNE & PURLEY TILEHURST CP CP P CALCOT Q CENTRAL GREAT R NORTH YATTENDON R SHEFFORD CP CP PANGBOURNE TIDMARSH CP SULHAM CP CHIEVELEY CP FRILSHAM CP TILEHURST CP CHIEVELEY TILEHURST & COLD ASH BRADFIELD BIRCH HERMITAGE WINTERBOURNE CP CP CP COPSE WELFORD CP Q P BOXFORD STANFORD TILEHURST