How to Study Power and Saints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Southern Denmark

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN DENMARK THE CHRISTIAN KINGDOM AS AN IMAGE OF THE HEAVENLY KINGDOM ACCORDING TO ST. BIRGITTA OF SWEDEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF HISTORY, CULTURE AND CIVILISATION CENTRE FOR MEDIEVAL STUDIES BY EMILIA ŻOCHOWSKA ODENSE FEBRUARY 2010 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my work, I had the privilege to be guided by three distinguished scholars: Professor Jacek Salij in Warsaw, and Professors Tore Nyberg and Kurt Villads Jensen in Odense. It is a pleasure to admit that this study would never been completed without the generous instruction and guidance of my masters. Professor Salij introduced me to the world of ancient and medieval theology and taught me the rules of scholarly work. Finally, he encouraged me to search for a new research environment where I could develop my skills. I found this environment in Odense, where Professor Nyberg kindly accepted me as his student and shared his vast knowledge with me. Studying with Professor Nyberg has been a great intellectual adventure and a pleasure. Moreover, I never would have been able to work at the University of Southern Denmark if not for my main supervisor, Kurt Villads Jensen, who trusted me and decided to give me the opportunity to study under his kind tutorial, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The trust and inspiration I received from him encouraged me to work and in fact made this study possible. Karen Fogh Rasmussen, the secretary of the Centre of Medieval Studies, had been the good spirit behind my work. -

Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages

jussi hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Studia Fennica Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Jussi Hanska Strategies of Sanity and Survival Religious Responses to Natural Disasters in the Middle Ages Finnish Literature Society · Helsinki Studia Fennica Historica 2 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2002 Jussi Hanska and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2002 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: eLibris Media Oy ISBN 978-951-746-357-7 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-818-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-819-2 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 0355-8924 (Studia Fennica Historica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sfh.2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. -

The Linköping Mitre Ecclesiastical Textiles and Episcopal Identity

CHAPTER 9 THE LINKÖPING MITRE ECCLESIASTICAL TEXTILES AND EPISCOPAL IDENTITY Ingrid Lunnan Nødseth Questions of agency have been widely discussed in art history studies in recent decades, with scholars such as Alfred Gell and W. T. Mitchell arguing that works of art possess the qualities or powers of living beings. Recent scholar ship has questioned whether Max Weber’s notion of charisma as a personal quality can be extended to the realm of things such as charismatic objects or charismatic art. Textiles are particularly interesting in this regard, as clothing transforms and extends the corporal body acting as a ‘social skin’, this prob lematizes the human/object divide. As such, ecclesiastical dress could be con sidered part of the priest’s social body, his identity. The mitre was especially symbolic and powerful as it distinguished the bishop from the lower ranks of the clergy. This article examines the richly decorated Linköping mitre, also known as Kettil Karlsson’s mitre as it was most likely made for this young and ambitious bishop in the 1460s. I argue that the aesthetics and rhetoric of the Linköping mitre created charismatic effects that could have contributed to the charisma of Kettil Karlsson as a religious and political leader. This argument, however, centers not so much on charismatic objects as on the relationship between personal charisma and cultural objects closely identified with char ismatic authority. The Swedish rhyme chronicle Cronice Swecie describes [In Linköping I laid down my episcopal vestments how bishop Kettil Karlsson in 1463 stripped himself of and took up both shield and spear / And equipped his episcopal vestments (biscopsskrud) in the cathedral myself as a warrior who can break lances in combat.] of Linköping, only to dress for war with shield and spear (skiöll och spiwt) like any man who could fight well with This public and rhetorical event transformed the young a lance in combat: bishop from a man of prayer into the leader of a major army. -

88 Foundation of the Pirita Convent, 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources

88 Ruth Rajamaa Foundation of the Pirita Convent, known to researchers of the Birgittine Order 1407–1436, in Swedish Sources but, together with other Swedish sources, it Ruth Rajamaa is possible to discover new aspects in the Summary relations between the Pirita and Vadstena convents. Abstract: This article is largely based on Vadstena was the mother abbey of the Order Swedish sources and examines the role of of the Holy Saviour, Ordo Sancti Salvatoris. the Vadstena abbey in the history of the The founder, Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303 Pirita convent, from the founding of its 1373), had a revelation in 1346: Christ gave daughter convent in 1407 until the conse- her the constitution of a new order. In 1349, cration of the independent convent in 1431. Birgitta left Sweden and settled in Rome in Various aspects of the Vadstena abbey’s order to personally ask permission from the patronage are pointed out, revealing both pope to found a new order. The Order of the a helpful attitude and interfering guid- Holy Saviour was confirmed in 1370 and ance. Vadstena paid more attention to again in 1378 under the Augustinian Rule, Pirita than to other Birgittine monasteries with the addition of the Rule of the Holy and had many brothers and sisters of its Saviour, Ordo sancti Augustini sancti Sal- monastery there. Such closeness to the vatoris nuncupatus. mother monastery is a totally new pheno- The main aim of the Birgittine Order was menon in the history of researching Pirita, to purify all Christians; it was established and still needs more thorough analysis. -

Sweden and the Five Hundred Year Reformation Anamnesis a Catholic

Sweden and the Five Hundred Year Reformation Anamnesis A Catholic Perspective Talk by Clemens Cavallin at the The Roman Forum, Summer Symposium, June 2016, Gardone, Italy. To Remember the Reformation According to Collins Concise Dictionary, “Commemoration” means, “to honour or keep alive the memory of.”1 It is weaker than the wording “Reformation Jubilee,” which generated 393 000 hits on Google, compared with merely 262 000 for “Reformation Commemoration.”2 According to the same dictionary, the meaning of “Jubilee” is “a time or season for rejoicing.” For a Swedish Catholic, there is, however, little to rejoice about when considering the consequences of the reformation; instead, the memories that naturally come to mind are those of several centuries of persecution, repression and marginalization.3 The rejoicing of a jubilee is, hence, completely alien for a Swedish Catholic when looking back to the reformation, but it is also difficult to acquiesce to the weaker meaning of “honoring” the reformation, as implied by the notion of commemoration. The reformation in Sweden was not especially honorable. The second part of the meaning of commemoration “to keep alive the memory of” is more suitable, but then in a form of a tragic remembering; we grieve over what we have lost. In the village where I live, for example, there is a beautiful white stone church from the 12th century. It was thus Catholic for five hundred years before the reformation, but has since then been a Lutheran Church. Instead, I have to travel by car for half an hour to attend mass in the Catholic Church, which is a former protestant Free Church chapel from the 1960s.4 All the priests are Polish, and so is, I guess, half the parish. -

'Cum Organum Dicitur'

‘Cum organum dicitur’ The transmission of vocal polyphony in pre-Reformation Sweden and bordering areas Erik Bergwall C-uppsats 2016 Institutionen för musikvetenskap Uppsala universitet Abstract Erik Bergwall: ‘Cum organum dicitur’ – The transmission of vocal polyphony in pre-Reformation Sweden and bordering areas. Uppsala University, Department of Musicology, 2016. Keywords: polyphony, organum, discant, Swedish music, the Middle Ages, oral transmission. The polyphonic sources of medieval Sweden are very few, although well-documented in musicological research. However, while most of the earlier research has tended to focus on interpreting the sources themselves rather than to examine the cultural and historical context in which they were written, the present dissertation aims at providing a broader narrative of the transmission and practice of polyphony. By examining the cultural context of the sources and putting them in relation to each other, a bigger picture is painted, where also Danish and Norwegian sources are included. Based on the discussion and analyses of the sources, a general historical outline is suggested. The practice of organum in the late 13th century in Uppsala was probably a result from Swedes studying in Paris and via oral transmission brought the practice back home. This ‘Parisian path’ was accompanied by an ‘English-Scandinavian’ path, where mostly Denmark and Norway either influenced or were influenced by English polyphonic practice. During the 14th century, polyphony seems to have been rather established in Sweden, although prohibitions against it were made by the Order of the Bridgettines. These prohibitions were probably linked to a general anti- polyphonic attitude in Europe, beginning with the papal bull of John XII in 1324. -

Sneak Preview -- Please Report Errors to [email protected] Report Errors -- Please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events

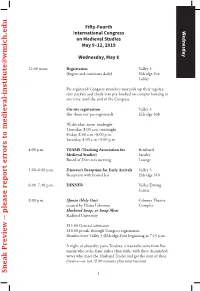

Fifty-Fourth International Congress Wednesday on Medieval Studies May 9–12, 2019 Wednesday, May 8 12:00 noon Registration Valley 3 (begins and continues daily) Eldridge-Fox Lobby Pre-registered Congress attendees may pick up their registra- tion packets and check into pre-booked on-campus housing at any time until the end of the Congress. On-site registration Valley 3 (for those not pre-registered) Eldridge 308 Wednesday, noon–midnight Thursday, 8:00 a.m.–midnight Friday, 8:00 a.m.–8:00 p.m. Saturday, 8:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. 4:00 p.m. TEAMS (Teaching Association for Bernhard Medieval Studies) Faculty Board of Directors meeting Lounge 5:00–6:00 p.m. Director’s Reception for Early Arrivals Valley 3 Reception with hosted bar Eldridge 310 6:00–7:30 p.m. DINNER Valley Dining Center 8:00 p.m. Sfanta (Holy One) Gilmore Theatre created by Diana Lobontiu Complex Husband Swap, or Swap Meat Radford University $15.00 General admission $10.00 presale through Congress registration Shuttles leave Valley 3 (Eldridge-Fox) beginning at 7:15 p.m. A night of absurdity pairs Teodora, a wannabe saint from Ro- mania who seeks fame rather than faith, with three dissatisfied wives who meet the Husband Trader and get the men of their dreams—or not. (100 minutes plus intermission) Sneak Preview -- please report errors to [email protected] report errors -- please Preview Sneak 1 Thursday, May 9 Morning Events 7:00–9:00 a.m. BREAKFAST Valley Dining Center Thursday 8:30 a.m. -

The Church of Sweden in Continuous Reformation

Journal of the European Society of Women in Theological Research 25 (2017) 67-80. doi: 10.2143/ESWTR.25.0.3251305 ©2017 by Journal of the European Society of Women in Theological Research. All rights reserved. Ninna Edgardh Embracing the Future: The Church of Sweden in Continuous Reformation The whole world followed the events in Lund, Sweden, on October 31, 2016, when for the first time a joint ecumenical commemoration of the Reformation took place between the Lutheran World Federation (LWF) and the Roman-Catholic Church. A photo distributed worldwide shows Pope Francis and the Archbishop of the Church of Sweden, Antje Jackelén, embracing each other. The photo contains both hope and tension. The Church of Sweden tries to balance the tension between its heritage as ecumenical bridge-builder, launched already by Archbishop Nathan Söderblom a hundred years ago, and its pioneering role with regard to issues of gen- der and sexuality. These seemingly contradictory roles are hereby set into the wider context of the journey Sweden has made from the time of the Lutheran reformation up to the present. A uniform society characterised by one people and one Christian faith, has gradually transformed into a society where faith is a voluntary option. The former state church faces new demands in handling religious as well as cultural diversities. Leadership is increasingly equally shared between women and men. The Church of Sweden holds all these tensions together through the approach launched on the official website of a church in constant need of reform. Por primera vez la Federación Luterana Mundial y la Iglesia Católica Romana celebraron conjuntamente una conmemoración ecuménica de la Reforma un hecho que ocurrió en Lund, Suecia, el 31 de octubre de 2016 y que fue ampliamente difundido por el mundo, a través de una fotografía distribuida globalmente donde aparecen abrazándose el Papa Francisco de la Iglesia Católica y la arzobispa Antje Jackelén de la iglesia de Suecia, reflejando esperanza y tensión a la vez. -

The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena Lisa Tagliaferri Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2154 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LYRICAL MYSTICISM: THE WRITING AND RECEPTION OF CATHERINE OF SIENA by LISA TAGLIAFERRI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 © Lisa Tagliaferri 2017 Some rights reserved. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Images and third-party content are not being made available under the terms of this license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ii Lyrical Mysticism: The Writing and Reception of Catherine of Siena by Lisa Tagliaferri This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 19 April 2017 Clare Carroll Chair of Examining Committee 19 April 2017 Giancarlo Lombardi Executive -

The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches

CM 2014 ombrukket3.qxp_CM 30.04.15 15.46 Side 114 The Use of Marian Sculptures in Late Medieval Swedish Parish Churches JONAS CARLQUIST This article discusses the use of wooden Marian sculptures in Swedish parish churches during the Middle Ages. By analysing the Marian sculptures’ context, design and mate- riality together with vernacular devotional literature, I suggest that these different media together collaborated in the education of the lay congregation about the life of the Virgin and her cult. Together, sculptures and prayers facilitated private meditation. I will use the Madonna of Knutby Church as my leading example. Introduction Located in the Swedish arch-diocese of Uppland, Knutby is a small parish with a 13th century, church situated close to Uppsala. The church’s patron is St Martin of Tours, but its interior also contains many images of the Virgin Mary. Among other objects, the church contains an Apocalyptic Madonna from the late 15th century (according to Swedish history Museum, Stockholm). During the late medieval period in Swe- den, namely in the 15th and 16th centuries, many examples of such Madonnas were locally produced for parish churches, and apocalyptic Madonnas were also imported into Sweden, usually from northern Germany or the netherlands (see for example Andersson 1980: 64–78). In this article, I will discuss the reasons behind the design, the intertextuality (i.e. the shaping of a text’s meaning by another text by for example allusion, quotation), and the congregation’s assumed perception of the Madonna of Knutby to provide a deeper understanding of the general use of wooden Marian sculptures in medieval Sweden. -

Continuity and Change

Continuity and Change PAPERS FROM THE BIRGITTA CONFERENCE AT DARTINGTON 2015 Editors Elin Andersson, Claes Gejrot, E. A. Jones & Mia Åkestam KONFERENSER 93 KUNGL. VITTERHETS HISTORIE OCH ANTIKVITETS AKADEMIEN MIA ÅKESTAM Creating Space Queen Philippa and Art in Vadstena Abbey RINCESS PHILIPPA OF ENGLAND sailed into the harbour of Helsing- borg in September 1406 with ten ships and four balingers. She was 12 P years old, and arrived as queen of her new realms: Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Philippa had already married the King Erik of Pomerania par procuration in Westminster Abbey in December 1405, with the Swedish knight Ture Bengtsson (Bielke) as the king’s deputy at the ceremony. Now the marriage was to be repeated in Lund, this time with the king present. Philippa showed up with a retinue of 204 named persons, all wearing uniform dress in green and scarlet, accordingly furred and lined, with embroidered white crowns and the motto ‘sovereyne’ on one shoulder. Each badge was embroidered in accordance with the carriers’ social position.1 Te English escort exceeded 500 persons with servants and sailors included. Her trousseaux – the dowry – was extensive, and carefully recorded by the Royal Household. It is evident that the queen’s arrival was intended to be impressive. As an English princess, Philippa was also a representative of the Royal House of Lancaster, which naturally involved rank and power. She was the youngest daughter of King Henry IV and Mary de Bohun, born shortly before or on 4 July 1394 (her mother died that day, after giving birth to Philippa). One of her brothers was the famous king Henry V, victor at the battle of Agincourt 1415. -

The Churches of the Holy Land in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries 198

Tracing the Jerusalem Code 1 Tracing the Jerusalem Code Volume 1: The Holy City Christian Cultures in Medieval Scandinavia (ca. 1100–1536) Edited by Kristin B. Aavitsland and Line M. Bonde The research presented in this publication was funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN), project no. 240448/F10. ISBN 978-3-11-063485-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063943-8 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063627-7 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110639438 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020950181 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Kristin B. Aavitsland and Line M. Bonde, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Cover illustration: Wooden church model, probably the headpiece of a ciborium. Oslo University Museum of Cultural history. Photo: CC BY-SA 4.0 Grete Gundhus. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI Books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com In memory of Erling Sverdrup Sandmo (1963–2020) Contents List of Maps and Illustrations XI List of Abbreviations XVII Editorial comments for all three volumes XIX Kristin B. Aavitsland, Eivor Andersen Oftestad, and Ragnhild Johnsrud