Enforcement Instruments for Social Human Rights Along Supply Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lorbeer Und Sterne

Thema: Strittige Arzneimittelstudien AMERIKA HAT GEWÄHLT EUROPA IM DILEMMA Überraschungssieger Trump schockt Der EU-Handelsvertrag Ceta und die Bundestag beschließt Gesetz SEITE 1-3 die Eliten weltweit SEITE 4,5 Tücken der Mitwirkung SEITE 9 Berlin, Montag 14. November 2016 www.das-parlament.de 66. Jahrgang | Nr. 46-47 | Preis 1 € | A 5544 KOPF DER WOCHE Überraschend Wahlsieger Vorrang für die Forschung Donald Trump Er ist einer der spektakulärsten Wahlsieger der US-Geschichte: Der Immobilien- milliardär und Republikaner Donald Trump siegte GESUNDHEIT Bundestag erweitert Möglichkeiten für klinische Arzneimittelstudien an Demenzkranken bei der Präsidenten- wahl gegen die aller- meisten Vorhersagen eichskanzler Otto von Bis- über die favorisierte marck (1815-1898) soll demokratische Geg- mal gesagt haben, je weni- nerin Hillary Clinton. ger die Leute davon wüss- Der oft polternde ten, wie Würste und Geset- Trump hatte sich im ze gemacht werden, desto Wahlkampf als An- besserR könnten sie schlafen. Das Bonmot walt der von der Glo- stammt allerdings aus einer Zeit, als die balisierung bedrohten parlamentarischen und demokratischen © picture-alliance/dpa und „vergessenen“ Gepflogenheiten in Deutschland noch un- Amerikaner profiliert und dabei auch illegale Im- terentwickelt waren. Heute wird bei der migranten und Muslime mit scharfen Worten ins Gesetzgebung meist auf eine breite Beteili- Visier genommen. Wofür er letztlich innen- und gung und Transparenz geachtet, allerdings außenpolitisch steht, blieb unklar. In jedem Fall kommt es vor, dass -

Annual Report 2017-2018

US Governor Philip D. Murphy (New Jersey) Annette Riedel, Senior Editor, Deutschlandfunk Kultur Berlin Transatlantic Forum 2018: “Present at the New Creation? Tech. Power. Democracy.” October 16, 2018 3 4 PREFACE Dear Friends of Aspen Germany, In 2017, we also had three US mayors in quick succession as guests of Aspen Germany: Mayor Pete Buttigieg of 2017 and 2018 were years of world-wide political and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles, economic changes. The international order, established and Mayor Rahm Emanuel from Chicago. All three events 70 years ago under US leadership after World War II, is attracted high-ranking transatlanticists from the Bundestag, now being challenged by the rise of populism, the rise of think tanks, and political foundations as well as business authoritarian regimes from Russia, China, Turkey, and representatives. The goal of these events was to facilitate a fundamental changes in US policy under President Donald transatlantic discussion about the future course of the Trump. United States after Trump’s election. In the last two years, we have seen an erosion in the core of Throughout both years, we have also continued our our transatlantic alliance. From NATO and our common transatlantic exchange programs. The Bundestag and security interests to our trade relations, from our approach &RQJUHVV6WD൵HUV([FKDQJH3URJUDPEURXJKWVWD൵HUVIURP to climate change to arms control – everything we have WKH86&RQJUHVVWR%HUOLQDQGVWD൵HUVIURPWKH*HUPDQ taken for granted as a stable framework of transatlantic Bundestag to Washington, D.C.. Over the years, we have relations is now being questioned. These dramatic changes built a robust network of young American and German did not go unnoticed by us. -

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 17/11815

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 17/11815 17. Wahlperiode 11. 12. 2012 Änderungsantrag der Abgeordneten Burkhard Lischka, Christine Lambrecht, Rainer Arnold, Edelgard Bulmahn, Sebastian Edathy, Petra Ernstberger, Gabriele Fograscher, Dr. Edgar Franke, Martin Gerster, Iris Gleicke, Günter Gloser, Ulrike Gottschalck, Dr. Gregor Gysi, Hans-Joachim Hacker, Michael Hartmann (Wackernheim), Dr. Rosemarie Hein, Dr. Barbara Hendricks, Gustav Herzog, Josip Juratovic, Dr. h. c. Susanne Kastner, Ulrich Kelber, Daniela Kolbe (Leipzig), Niema Movassat, Dr. Rolf Mützenich, Aydan Özog˘uz, Johannes Pflug, Joachim Poß, Dr. Sascha Raabe, Stefan Rebmann, Anton Schaaf, Paul Schäfer (Köln), Marianne Schieder (Schwandorf), Swen Schulz (Spandau), Sonja Steffen, Kerstin Tack, Kathrin Vogler, Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul, Waltraud Wolff (Wolmirstedt) zu der zweiten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung – Drucksachen 17/11295, 17/11800, 17/11814 – Entwurf eines Gesetzes über den Umfang der Personensorge bei einer Beschneidung des männlichen Kindes Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: 1. In Artikel 1 wird § 1631d wie folgt geändert: a) Absatz 1 wird wie folgt gefasst: „(1) Die Personensorge umfasst auch das Recht, nach vorangegangener ärztlicher Aufklärung in eine medizinisch nicht erforderliche Beschnei- dung des nicht einsichts- und urteilsfähigen männlichen Kindes einzu- willigen, wenn diese nach den Regeln der ärztlichen Kunst durchgeführt werden soll. Dies gilt nicht, wenn durch die Beschneidung auch unter Be- rücksichtigung ihres Zwecks das Kindeswohl gefährdet -

Vorstände Der Parlamentariergruppen in Der 18. Wahlperiode

1 Vorstände der Parlamentariergruppen in der 18. Wahlperiode Deutsch-Ägyptische Parlamentariergruppe Vorsitz: Karin Maag (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Dr. h.c. Edelgard Bulmahn (SPD) stv. Vors.: Heike Hänsel (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Dr. Franziska Brantner (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe Arabischsprachige Staaten des Nahen Ostens (Bahrain, Irak, Jemen, Jordanien, Katar, Kuwait, Libanon, Oman, Saudi Arabien, Syrien, Vereinigte Arabische Emirate, Arbeitsgruppe Palästina) Vorsitz: Michael Hennrich (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Gabriele Groneberg (SPD) stv. Vors.: Heidrun Bluhm (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Luise Amtsberg (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe ASEAN (Brunei, Indonesien, Kambodscha, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippinen, Singapur, Thailand, Vietnam) Vorsitz: Dr. Thomas Gambke (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) stv. Vors.: Dr. Michael Fuchs (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Johann Saathoff (SPD) stv. Vors.: Caren Lay (DIE LINKE.) Deutsch-Australisch-Neuseeländische Parlamentariergruppe (Australien, Neuseeland, Ost-Timor) Vorsitz: Volkmar Klein(CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Rainer Spiering (SPD) stv. Vors.: Cornelia Möhring (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Anja Hajduk (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Deutsch-Baltische Parlamentariergruppe (Estland, Lettland, Litauen) Vorsitz: Alois Karl (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: René Röspel (SPD) stv. Vors.: Dr. Axel Troost (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Dr. Konstantin von Notz (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Deutsch-Belarussische Parlamentariergruppe Vorsitz: Oliver Kaczmarek (SPD) stv. Vors.: Dr. Johann Wadephul (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Andrej Hunko (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: N.N. (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) 2 Deutsch-Belgisch-Luxemburgische Parlamentariergruppe (Belgien, Luxemburg) Vorsitz: Patrick Schnieder (CDU/CSU) stv. Vors.: Dr. Daniela de Ridder (SPD) stv. Vors.: Katrin Werner (DIE LINKE.) stv. Vors.: Corinna Rüffer (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) Parlamentariergruppe Bosnien und Herzegowina Vorsitz: Marieluise Beck (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) stv. -

RTF Template

19. Wahlperiode Verteidigungsausschuss Mitteilung Berlin, den 17. Oktober 2019 Die 42. Sitzung des Verteidigungsausschusses Sekretariat findet statt am Telefon: +49 30 227-32537 Fax: +49 30 227-36005 Mittwoch, dem 23. Oktober 2019, 9:00 Uhr Berlin, Paul-Löbe-Haus Sitzungssaal Sitzungssaal: 2.700 Telefon: +49 30 227-30481 Fax: +49 30 227-36481 Handys im Sitzungssaal bitte ausschalten! Tagesordnung Tagesordnungspunkt 1 Allgemeine Bekanntmachungen Tagesordnungspunkt 2 Bericht der Bundesregierung über die Lage Berichterstatter/in: in den Einsatzgebieten der Bundeswehr Abg. Prof. h. c. Dr. Karl A. Lamers [CDU/CSU] Abg. Dr. Fritz Felgentreu [SPD] Abg. Jan Nolte [AfD] Abg. Dr. Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann [FDP] Abg. Dr. Alexander S. Neu/ Abg. Tobias Pflüger [DIE LINKE.] Abg. Dr. Tobias Lindner [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN] 19. Wahlperiode Seite 1 von 9 Verteidigungsausschuss Tagesordnungspunkt 3 Angelegenheiten der Gemeinsamen Sicherheits- und Verteidigungspolitik in Europa Tagesordnungspunkt 4 Gesetzentwurf der Bundesregierung Federführend: Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Modernisierung der Mitberatend: Strukturen des Besoldungsrechts Verteidigungsausschuss und zur Änderung weiterer dienstrechtlicher Haushaltsausschuss (mb und § 96 GO) Vorschriften Gutachtlich: (Besoldungsstrukturenmodernisierungsgesetz - Parlamentarischer Beirat für nachhaltige Entwicklung BesStMG) Berichterstatter/in: Abg. Kerstin Vieregge [CDU/CSU] BT-Drucksache 19/13396 Abg. Dr. Fritz Felgentreu [SPD] Abg. Jan Nolte [AfD] Abg. Dr. Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann [FDP] Abg. Matthias Höhn [DIE LINKE.] Abg. Dr. Tobias Lindner [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN] Frist für die Abgabe der Voten: 23.10.2019 19. Wahlperiode Tagesordnung Seite 2 von 9 42. Sitzung Verteidigungsausschuss Tagesordnungspunkt 5 Antrag der Abgeordneten Matthias Höhn, Jan Korte, Federführend: Dr. Gesine Lötzsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Ausschuss für Inneres und Heimat Fraktion DIE LINKE. -

Plenarprotokoll 17/45

Plenarprotokoll 17/45 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 45. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 9. Juni 2010 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 1 Britta Haßelmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 4522 D Befragung der Bundesregierung: Ergebnisse der Klausurtagung der Bundesregierung Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister über den Haushalt 2011 und den Finanz- BMF . 4522 D plan 2010 bis 2014 . 4517 A Bettina Kudla (CDU/CSU) . 4523 C Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister BMF . 4517 B BMF . 4523 C Alexander Bonde (BÜNDNIS 90/ Elke Ferner (SPD) . 4524 A DIE GRÜNEN) . 4518 C Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister BMF . 4524 B BMF . 4518 D Carsten Schneider (Erfurt) (SPD) . 4519 B Tagesordnungspunkt 2: Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister BMF . 4519 C Fragestunde (Drucksachen 17/1917, 17/1951) . 4524 C Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) (CDU/CSU) . 4520 A Dringliche Frage 1 Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister Elvira Drobinski-Weiß (SPD) BMF . 4520 A Konsequenzen aus Verunreinigungen und Alexander Ulrich (DIE LINKE) . 4520 B Ausbringung von mit NK603 verunreinig- Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister tem Saatgut in sieben Bundesländern BMF . 4520 C Antwort Joachim Poß (SPD) . 4521 A Dr. Gerd Müller, Parl. Staatssekretär BMELV . 4524 C Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister Zusatzfragen BMF . 4521 B Elvira Drobinski-Weiß (SPD) . 4525 A Dr. h. c. Jürgen Koppelin (FDP) . 4521 D Dr. Christel Happach-Kasan (FDP) . 4525 C Friedrich Ostendorff (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister DIE GRÜNEN) . 4526 A BMF . 4522 A Kerstin Tack (SPD) . 4526 D Rolf Schwanitz (SPD) . 4522 B Cornelia Behm (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 4527 C Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Bundesminister Bärbel Höhn (BÜNDNIS 90/ BMF . 4522 B DIE GRÜNEN) . -

Stimmzettel Bundestagswahl 2013 130730.Indd

Stimmzettel für die Wahl zum Deutschen Bundestag im Wahlkreis 224 Starnberg am 22. September 2013 Sie haben 2 Stimmen hier 1 Stimme hier 1 Stimme für die Wahl für die Wahl eines/einer Wahlkreis- einer Landesliste (Partei) abgeordneten - maßgebende Stimme für die Verteilung der Sitze insgesamt auf die einzelnen Parteien - Erststimme Zweitstimme 1 Radwan, Alexander Christlich-Soziale Union 1 Christlich-Soziale in Bayern e.V. Dipl.-Ing. (FH), CSU Union in Bayern e.V. CSU Gerda Hasselfeldt, Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich, Rechtsanwalt, MdL Dr. Peter Ramsauer, Alexander Dobrindt, Rottach-Egern Marlene Mortler 2 Barthel, Klaus Sozialdemokratische Partei 2 Sozialdemokratische Deutschlands MdB SPD Partei Deutschlands SPD Florian Pronold, Anette Kramme, Kochel a. See Martin Burkert, Gabriele Fograscher, Klaus Barthel 3 Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, Sabine Freie Demokratische Partei 3 Freie Demokratische Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger, Bundesministerin, FDP Partei FDP Horst Meierhofer, Miriam Gruß, MdB Marina Schuster, Jimmy Schulz Feldafing 4 Bär, Karl BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 4 BÜNDNIS 90/ Claudia Roth, Dr. Anton Hofreiter, Agrarökonom GRÜNE DIE GRÜNEN GRÜNE Ekin Deligöz, Dieter Janecek, Holzkirchen Elisabeth Scharfenberg 5 Wagner, Andreas DIE LINKE 5 Klaus Ernst, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Heilerziehungspfleger DIE LINKE DIE LINKE DIE LINKE Nicole Gohlke, Harald Weinberg, Geretsried Nicole Fritsche 6 Müller, Fabian Piratenpartei Deutschland 6 Piratenpartei Bruno Kramm, Alexander Bock, Student PIRATEN Deutschland PIRATEN Andreas Popp, Stefan Körner, Starnberg Patrick Linnert Nationaldemokratische 7 Partei Deutschlands NPD Karl Richter, Sigrid Schüßler, Sascha Roßmüller, Ralf Ollert, Manfred Waldukat 8 Jenne, Helmut Ökologisch-Demokratische 8 Ökologisch- Partei Dipl.-Betriebsw. (FH), ÖDP Demokratische Partei ÖDP Claudia Wiest, Gabriela Schimmer-Göresz, EDV-Fachmann Sebastian Frankenberger, Christiane Lüst, Schliersee Dr. -

Plenarprotokoll 19/229

Plenarprotokoll 19/229 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 229. Sitzung Berlin, Mittwoch, den 19. Mai 2021 Inhalt: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Stefan Keuter (AfD) . 29247 C nung . 29225 B Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29247 C Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 8, 9, 10, Stefan Keuter (AfD) . 29247 D 16 b, 16 e, 21 b, 33, 36 und 39 . 29230 C Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29247 D Ausschussüberweisungen . 29230 D Sepp Müller (CDU/CSU) . 29248 A Feststellung der Tagesordnung . 29232 B Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29248 B Sepp Müller (CDU/CSU) . 29248 C Zusatzpunkt 1: Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29248 C Aktuelle Stunde auf Verlangen der Fraktio- Christian Dürr (FDP) . 29248 D nen der CDU/CSU und SPD zu den Raketen- angriffen auf Israel und der damit verbun- Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29249 A denen Eskalation der Gewalt Christian Dürr (FDP) . 29249 B Heiko Maas, Bundesminister AA . 29232 B Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29249 C Armin-Paulus Hampel (AfD) . 29233 C Dr. Wieland Schinnenburg (FDP) . 29250 A Dr. Johann David Wadephul (CDU/CSU) . 29234 C Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29250 A Alexander Graf Lambsdorff (FDP) . 29235 C Dorothee Martin (SPD) . 29250 B Dr. Gregor Gysi (DIE LINKE) . 29236 C Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29250 B Omid Nouripour (BÜNDNIS 90/ Dorothee Martin (SPD) . 29250 C DIE GRÜNEN) . 29237 C Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29250 D Dirk Wiese (SPD) . 29238 C Lisa Paus (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) . 29250 D Dr. Anton Friesen (AfD) . 29239 D Olaf Scholz, Bundesminister BMF . 29251 A Jürgen Hardt (CDU/CSU) . 29240 B Dr. Gesine Lötzsch (DIE LINKE) . 29251 C Kerstin Griese (SPD) . -

PDF Herunterladen, PDF, 145 KB, Nicht Barrierefrei

BULLETIN DER BUNDESREGIERUNG Nr. 107-1 vom 27. Oktober 2009 Ansprache des Alterspräsidenten des Deutschen Bundestages, Dr. Heinz Riesenhuber, zur Eröffnung der konstituierenden Sitzung des 17. Deutschen Bundestages am 27. Oktober 2009 in Berlin: Guten Morgen, meine sehr verehrten Damen und Herren! Liebe Kolleginnen und Kollegen, ich begrüße Sie zur konstituierenden Sitzung des 17. Deutschen Bundestags. Parlamentarischer Brauch ist es – das entspricht unserer Geschäftsordnung; ich kann die Paragrafen zitieren –, dass der Älteste die erste Sitzung des Bundestags eröffnet. Ich bin am Sonntag, dem 1. Dezember 1935, geboren. Wenn jemand von den Kollegen im Saal älter ist als ich, dann spreche er jetzt oder er schweige für im- mer. Unser Präsident würde sagen: Ich höre und sehe keinen Widerspruch. Meine Damen und Herren, damit rufe ich Punkt 1 der Tagesordnung auf: Eröffnung der Sitzung durch den Alterspräsidenten. Ich eröffne die erste Sitzung in der 17. Wahlperiode. Ich begrüße den Herrn Bundespräsidenten. Wir freuen uns, Herr Bundespräsident, dass Sie wieder bei uns sind. Bulletin Nr. 107-1 v. 27. Okt. 2009 / Alterspräs. Riesenhuber – Eröffn. konst. Sitzung des 17. Dt. BT - 2 - Ich begrüße herzlich die ehemalige Präsidentin des Deutschen Bundestages, Frau Dr. Rita Süssmuth. Sie haben uns mit Würde und Klugheit über die Jahre geführt – die Verbundenheit bleibt. Ich habe die Freude, Botschafter und Missionschefs zahlreicher Staaten hier zu be- grüßen. Sie alle sind herzlich willkommen – in der Verbundenheit der Gemeinschaft der Völker. Ich darf einen einzigen Kollegen besonders begrüßen, weil er heute mit uns seinen Geburtstag feiert, die schönste Party, die man sich vorstellen kann. Es ist der Kollege Henning Otte, dem ich herzlich gratuliere. -

Anette Kramme

SOMMERZEIT DIE ZEITUNG ZUR BUNDESTAGSWAHL Anette Kramme Aus der Stadt Aus dem Land Über Erfolge und Misserfolge Graserschule, Kultur in Bay- Ferienprogramme der SPD, in der Regierungskoalition reuth, Stadtarchiv, Kinder Aus der Fraktion / Seite 03 / Seiten 08/09 / Seiten 10/11 Mehr Zeit für Familie – auch nach den Ferien Wie geht das? / Seite 02 2 / FAMILIE FAMILIENARBEITSZEIT Mehr Zeit für Familie – auch nach den Ferien Was fehlt Familien in Deutschland? Zeit oder Geld – oft auch beides. Die SPD will es leichter machen, sich um seine Liebsten zu kümmern. Schließlich ist es das, was Familie ausmacht. „Für mich ist Familie dort, wo Menschen für- einander Verant wortung übernehmen.“ Martin Schulz über den alleinerziehenden Vater bis zum les- bischen Paar“, sagt SPD-Kanzlerkandidat Martin Schulz. Es ist Zeit, sie zu entlasten. Die Familienarbeitszeit ist nur eine Maßnahme. Die SPD will auch den Rechtsanspruch auf Ganztagsbetreuung für Kita- und Schulkinder durchsetzen. So lernen und spielen Kinder zu- sammen, während ihre Eltern arbeiten. Danach müssen keine Hausaufgaben mehr erledigt werden, sondern es ist Zeit fürs gemeinsame Essen oder den Videoabend. Die Kita-Gebüh- Wenn mittags noch alle im Pyjama sind. Wenn Zeit für die Familie zu haben. Einen Teil des ren werden schrittweise abgeschafft. Denn Mama und Papa mal ein Buch auslesen kön- Lohnausfalls – genau gesagt 300 Euro – fängt Familie kostet Geld und wenn vom verdienten nen und trotzdem noch mit den Kindern Eis der Staat ab. Damit niemand mehr die ersten Lohn mehr übrig bleibt, hilft das schon viel. Aus essen gehen. Wenn morgens schon die Ba- Schritte des eigenen Kindes verpasst oder die diesem Grund sollen Familien mit dem Kinder- detasche gepackt wird. -

Plenarprotokoll 18/136

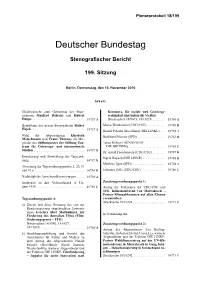

Textrahmenoptionen: 16 mm Abstand oben Plenarprotokoll 18/136 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 136. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 12. November 2015 Inhalt: Würdigung von Bundeskanzler a. D. Helmut Tagesordnungspunkt 5: Schmidt. 13233 A Antrag der Abgeordneten Sabine Zimmermann (Zwickau), Ulla Jelpke, Jutta Krellmann, wei- Erweiterung der Tagesordnung ............ 13234 D terer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Flüchtlinge auf dem Weg in Arbeit Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung ...... 13235 A unterstützen, Integration befördern und Lohndumping bekämpfen Begrüßung des Vorsitzenden des Auswär- Drucksache 18/6644 .................... 13250 A tigen Ausschusses des Europäischen Par- laments, Herrn Elmar Brok, und des Gene- Sabine Zimmermann (Zwickau) ralsekretärs der OSZE, Herrn Lamberto (DIE LINKE) ....................... 13250 B Zannier .............................. 13266 C Karl Schiewerling (CDU/CSU) ........... 13251 D Brigitte Pothmer (BÜNDNIS 90/ Tagesordnungspunkt 4: DIE GRÜNEN) ...................... 13253 C Vereinbarte Debatte: 60 Jahre Bundeswehr. 13235 B Katja Mast (SPD) ...................... 13254 C Henning Otte (CDU/CSU) ............... 13235 B Dr. Matthias Zimmer (CDU/CSU) ......... 13255 C Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) .......... 13236 D Sevim Dağdelen (DIE LINKE) ............ 13257 A Rainer Arnold (SPD) .................... 13238 A Kerstin Griese (SPD) ................... 13258 B Agnieszka Brugger (BÜNDNIS 90/ Brigitte Pothmer (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) .................... DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... -

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a)