UNDERSTANDING MARKETS in AFGHANISTAN: a Case Study of Carpets and the Andkhoy Carpet Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Traditions of Carpet Weaving in the Southern Regions of Uzbekistan

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- EPRA International Journal of Socio-Economic and Environmental Outlook (SEEO) ISSN: 2348-4101 Volume: 8 | Issue: 3| March 2021 | SJIF Impact Factor (2021): 7.426 | Journal DOI: 10.36713/epra0314 | Peer-Reviewed Journal THE TRADITIONS OF CARPET WEAVING IN THE SOUTHERN REGIONS OF UZBEKISTAN Davlatova Saodat Tilovberdiyevna Doctor of Science Of the National University of Uzbekistan, The Head of the «Applied Ethnology» laboratory Abdukodirov Sarvar Begimkulovich, Teacher of Jizzakh State Pedagogical University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan ANNOTATION In the article is enlightened local features of traditions of the Uzbek carpet weaving on examples of samples from southern regions (Kashkadarya and Surkhandarya regions) of Uzbekistan. Also, are shown distinctive features in the processes of preparing raw materials and weaving machines, including the dyeing process of yarns, and are also described types of carpets and their features. KEY WORDS: carpet weaving, craft, loom, types of carpets, wool, carpet products DISCUSSION At the end of the 19th century and at the Carpet weaving is a long developed rare beginning of the 20th century the main raw material type of textile, it has been continuing its traditions of carpet weaving was sheep wool. The carpet for ages[4]. Mainly women deal with carpet weaving weavers of the southern regions almost didn’t use the and they knit many household furnishings, felt rugs, wool brought from Russia. But, there is information felts, carpets and other carpet products. about that they used the products brought from Carpet weaving is basically tightly Afghanistan, Iran and Eastern Turkistan[14]. connected with livestock, it is developed in Andijan, On the carpets of Kashkadarya the Samarkand, Kashkadarya, Surkhandarya, Bukhara traditions of carpet weaving of desert livestock cities of Uzbekistan and lowlands of Amudarya and breeder tribes are seen. -

Update Conflict Displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013

Update conflict displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013 Background On 22 April, Anti-Government Elements (AGE) launched a major attack in Qaysar district, making Faryab province one of their key targets of the spring offensive. The fighting later spread to Almar district of Faryab province and Ghormach of Badghis Province, displacing approximately 2,500 people. The attack in Qaysar was well organized, involving several hundred AGE fighters. According to Shah Farokh Shah, commander of 300 Afghan local policemen in Khoja Kinti, some of the insurgents were identified as ‘Chechens and Pakistani Taliban’1. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) has regained control of the Qaysar police checkpoints. The plan is to place 60 Afghan local policemen (ALPs) at the various checkpoints in the Khoja Kinti area. Quick Response Forces with 40 ALPs have already been posted. ANSF is regaining control in Ghormach district. Similar efforts are made in Almar and Pashtun Kot. Faryab OCCT has decided to replace ALP and ANP, originally coming from Almar district, with staff from other districts. Reportedly the original ALP and ANP forces have sided with the AGE. Security along the Shiberghan - Andkhoy road has improved. The new problem area is the Andkhoy - Maymana road part. 200 highway policemen are being recruited to secure the Maymana - Shibergan highway. According to local media reports the Taliban forces have not been defeated and they are still present in the area. There may be further displacement in view of the coming ANSF operations. Since the start of this operation on 22 April, UNAMA documented 18 civilian casualties in Qaysar district from ground engagements between AGEs and ANSF, IED incidents targeting ANP and targeted killings. -

Gouvernance Des Coopératives Agricoles Dans Une Économie En Reconstruction Après Conflit Armé : Le Cas De L’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf

Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruction après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf To cite this version: Mohammad Edris Raouf. Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruc- tion après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan. Gestion et management. Université Paul Valéry- Montpellier III, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018MON30092. tel-03038739 HAL Id: tel-03038739 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03038739 Submitted on 3 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VALÉRY DE MONTPELLIER III ÉCOLE DOCTORALE ÉCONOMIE ET GESTION DE MONTPELLIER ED 231, LABORATOIRE ART- DEV (ACTEURS, RESSOURCES ET TERRITOIRES DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT), SUP-AGRO MONTPELLIER Gouvernanceou e a cedescoopéat des coopératives esag agricoles coesda dans su une eéco économie o ee en reconstruction après conflit armé, le cas de l’Afghanistan By: Mohammad Edris Raouf Under Direction of Mr. Cyrille Ferraton MCF -HDR en sciences économiques, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, -

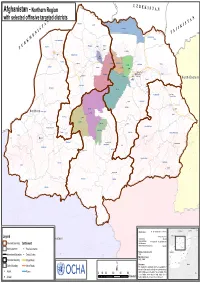

Download Map (PDF | 2.37

in te rn a tio n U a Z Khamyab l B Afghanistan - Northern Region E KIS T A N Qarqin with selected offinsive targeted districts A N Shortepa T N Kham Ab l a Qarqin n S o A i I t a n K T Shortepa r e t n S i JI I Kaldar N T A E Sharak Hairatan M Kaldar K Khani Chahar Bagh R Mardyan U Qurghan Mangajek Mangajik T Mardyan Dawlatabad Khwaja Du Koh Aqcha Aqcha Andkhoy Chahar Bolak Khwaja Du Koh Fayzabad Khulm Balkh Nahri Shahi Qaramqol Khaniqa Char Bolak Balkh Mazari Sharif Fayzabad Mazari Sharif Khulm Shibirghan Chimtal Dihdadi Nahri Shahi NorthNorth EasternEastern Dihdadi Marmul Shibirghan Marmul Dawlatabad Chimtal Char Kint Feroz Nakhchir Hazrati Sultan Hazrati Sultan Sholgara Chahar Kint Sholgara Sari Pul Aybak NorthernShirin Tagab Northern Sari Pul Aybak Qush Tepa Sayyad Sayyad Sozma Qala Kishindih Dara-I-Sufi Payin Khwaja Sabz Posh Sozma Qala Darzab Darzab Kishindih Khuram Wa Sarbagh Almar Dara-i-Suf Maymana Bilchiragh Sangcharak (Tukzar) Khuram Wa Sarbagh Sangcharak Zari Pashtun Kot Gosfandi Kohistanat (Pasni) Dara-I-Sufi Bala Gurziwan Ruyi Du Ab Qaysar Ruyi Du Ab Balkhab(Tarkhoj) Kohistanat Balkhab Kohistan Kyrgyzstan China Uzbekistan Tajikistan Map Doc Name: A1_lnd_eastern_admin_28112010 Legend CapitalCapital28 November 2010 Turkmenistan Jawzjan Badakhshan Creation Date: Kunduz Western WGS84 Takhar Western Balkh Projection/Datum: http://ochaonline.un.org/afghanistan Faryab Samangan Baghlan Provincial Boundary Settlement Web Resources: Sari Pul Nuristan Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:640,908 Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kunar Kabul !! Maydan -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’S Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

JANUARY 2011 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship between Aid and Security in Afghanistan’s Faryab Province Geert Gompelman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Author Geert Gompelman (MSc.) is a graduate in Development Studies from the Centre for International Development Issues Nijmegen (CIDIN) at Radboud University Nijmegen (Netherlands). He has worked as a development practitioner and research consultant in Afghanistan since 2007. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank his research colleagues Ahmad Hakeem (“Shajay”) and Kanishka Haya for their assistance and insights as well as companionship in the field. Gratitude is also due to Antonio Giustozzi, Arne Strand, Petter Bauck, and Hans Dieset for their substantive comments and suggestions on a draft version. The author is indebted to Mervyn Patterson for his significant contribution to the historical and background sections. Thanks go to Joyce Maxwell for her editorial guidance and for helping to clarify unclear passages and to Bridget Snow for her efficient and patient work on the production of the final document. -

Market Issue DESIGN FOCUS DESIGN D’Aquino Carl

DESIGN FOCUS Carl D’Aquino WINTER 2018 NORS 2018 Market Issue ATLANTA LAS VEGAS SOUMAK JANUARY 10 - 14, 2018 JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 1, 2018 COLLECTION (CLOSED 1/13) WORLD MARKET CENTER, AMERICASMART 4-G14 BUILDING B, B-0455 WWW.KALATY.COM view the Entire Collection momeni.com/eringates ATLANTA MARKET LAS VEGAS MARKET 4-B-2 January 10-14, 2018 B-425 January 28-February 1, 2018 Invite your customers to experience island-inspired living at its fi nest through the refi ned yet casual Tommy Bahama area rug collection. ATLANTA 3-A-2 | LAS VEGAS C395 | OWRUGS.COM/TOMMY AreaMag_OW_FULL_TOMMY_Nov2017.indd 1 10/31/17 3:23 PM ta m ar ian www.tamarian.com The Hygge Collection. Coming this January. ATLANTA 4-D-2 | DALLAS C-506 | VEGAS B-480 winter 2018 8.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 12/4/17 2:54 PM Page 6 From the President’s Desk Dear Colleagues, also well received. As you may know, we recently lost an icon in the In October, there were also shows staged by rug industry, Mr. Nasser Rahmanan. Mr. manufacturers and their trade associations. They Rahmanan was a leader and forerunner in our invited all of our members to visit them with industry. He always dedicated his complimentary airfare and accom- time for the betterment of the rug modations. Lucille and I met off i- industry. As a past president of cials of each trade association to dis- ORIA, a friend and a mentor, he cuss marketing and promotions of will be missed. Please read the arti- their respective country’s rugs here cle “In Memoriam” of Mr. -

An Investigation and Comparison of Strength Against the Compressive

ISSN (Print) : 2319-8613 ISSN (Online) : 0975-4024 Behzad Nikandish et al. / International Journal of Engineering and Technology (IJET) An Investigation and Comparison of Strength against the Compressive loads (Static and Dynamic) in 4 Iranian, Chinese, Uzbek, and Turkmen Types of Silk Used in Iran’s Hand-woven Carpets Behzad Nikandish Master student of Carpet, Kashan University Gholamreza Saleh Alavi Corresponding author, Faculty member of Carpet Department, Kashan University Email: [email protected] Abstract: The silk yarns are mostly used in carpet’s piles. Among the important attributes of the yarns used in the carpet’s piles is the strength against the static and dynamic load. In the current study, three woven samples from each of the four types as Iranian, Chinese, Turkmen, and Uzbek silks were extracted and through the required tests, the above-mentioned attributes were investigated and compared for them. The results indicate that against the static loads, the Chinese silk has the highest strength, and the Uzbek and Iranian silks are next, with a narrow difference. The Turkmen is ranked last in terms of strength. Also, the Iranian silk did best in strength against the dynamic loads, and it had the highest strength, with the Turkmen, Chinese, and Uzbek silks being after it with a marginal difference. The current study is conducted by the use of documentary and laboratory methods. Keywords: Silk, hand-woven carpet, Strength against static load, Strength against the dynamic load. 1- Introduction: The silk yarns have been long used in the production of beautiful and precious fabrics. These yarns, due to their unique attributes, are being used in many other industries. -

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward

Afghanistan National Railway Plan and Way Forward MOHAMMAD YAMMA SHAMS Director General & Chief Executive Officer Afghanistan Railway Authority Nov 2015 WHY RAILWAY IN AFGHANISTAN ? → The Potential → The Benefits • Affinity for Rail Transportation Pioneer Development of Modern – Primary solution for landlocked, Afghanistan developing countries/regions – At the heart of the CAREC and Become Part of the International ECO Program Rail Community – 75km of railroad vs 40,000 km of – Become long-term strategic partner road network to various countries – Rich in minerals and natural – Build international rail know-how resources – rail a more suitable (transfer of expertise) long term transportation solutions Raise Afghanistan's Profile as a than trucking. Transit Route • Country Shifting from Warzone – Penetrate neighbouring countries to Developing State Rail Market including China, Iran, Turkey and countries in Eastern – Improved connection to the Europe. community and the region (access – Standard Gauge has been assessed to neighbouring countries) as the preferred system gauge. – Building modern infrastructure – Dual gauge (Standard and Russian) in – Facilitate economic stability of North to connect with CIS countries modern Afghanistan STRATEGIC LOCATION OF AFGHANISTAN Kazakhstan China MISSING LINKS- and ASIAN RAILWAY TRANS-ASIAN RAILWAY NETWORK Buslovskaya St. Petersburg RUSSIAN FEDERATION Yekaterinburg Moscow Kotelnich Omsk Tayshet Petropavlovsk Novosibirsk R. F. Krasnoe Syzemka Tobol Ozinki Chita Irkutsk Lokot Astana Ulan-Ude Uralsk -

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan

Phosphate Occurrence and Potential in the Region of Afghanistan, Including Parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan By G.J. Orris, Pamela Dunlap, and John C. Wallis With a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn Open-File Report 2015–1121 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2015 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Suggested citation: Orris, G.J., Dunlap, Pamela, and Wallis, J.C., 2015, Phosphate occurrence and potential in the region of Afghanistan, including parts of China, Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, with a section on geophysics by Jeff Wynn: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2015-1121, 70 p., http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/ofr20151121. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. Contents -

Länderinformationen Afghanistan Country

Staatendokumentation Country of Origin Information Afghanistan Country Report Security Situation (EN) from the COI-CMS Country of Origin Information – Content Management System Compiled on: 17.12.2020, version 3 This project was co-financed by the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund Disclaimer This product of the Country of Origin Information Department of the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum was prepared in conformity with the standards adopted by the Advisory Council of the COI Department and the methodology developed by the COI Department. A Country of Origin Information - Content Management System (COI-CMS) entry is a COI product drawn up in conformity with COI standards to satisfy the requirements of immigration and asylum procedures (regional directorates, initial reception centres, Federal Administrative Court) based on research of existing, credible and primarily publicly accessible information. The content of the COI-CMS provides a general view of the situation with respect to relevant facts in countries of origin or in EU Member States, independent of any given individual case. The content of the COI-CMS includes working translations of foreign-language sources. The content of the COI-CMS is intended for use by the target audience in the institutions tasked with asylum and immigration matters. Section 5, para 5, last sentence of the Act on the Federal Office for Immigration and Asylum (BFA-G) applies to them, i.e. it is as such not part of the country of origin information accessible to the general public. However, it becomes accessible to the party in question by being used in proceedings (party’s right to be heard, use in the decision letter) and to the general public by being used in the decision. -

Afghanistan Review

1 20 October 2010 AFGHANISTAN REVIEW Inside This Issue Economic Stabilization This document is intended to provide an overview of relevant sector Governance & Participation events in Afghanistan from 14 October–19 October 2010. More Humanitarian Assistance comprehensive information is available on the Civil-Military Overview Infrastructure (CMO) at www.cimicweb.org. Hyperlinks to original source material are highlighted in blue and underlined in the embedded text. Justice & Reconciliation Security Social Well-Being For further information on CFC activities related to Afghanistan or inquiries about this publication, please contact the Afghanistan Team Manager: Valeria Davanzo, [email protected] or the Afghanistan Editor: Amber Ram- sey, [email protected] ECONOMIC STABILIZATION Steve Zyck, [email protected] / +1 757-683-4275 Back to top Afghanistan‟s Ministry of Finance (MoF) has released rity sector, increasing prices for basic foodstuffs and a „pre-budget report‟ which cites impressive gains in the uncertainty and unpredictability surrounding 2009/10 and projects growth in certain sectors in donor funding. 2010/11. Key highlights from the report include the following: Afghanistan‟s Investment Support Agency (AISA) also announced that the Afghan economy had The Afghan economy grew by 22.5% in benefited from USD 500 million in recorded invest- 2009/10, although growth is expected to slow to ment in 2009/10, showing a 6% increase from the 8.9% in 2010/11 and further drop to approxi- year prior. According to Tolo News, half of this mately 7% in 2011/12. However, the mining, amount was internal investment whereas the other financial services and transport sectors are an- half comprised foreign direct investment (FDI). -

Lot Description LOW Estimate HIGH Estimate 4000 Chinese Celadon

LOW HIGH Lot Description Estimate Estimate Chinese celadon glazed ceramic bottle vase, the yuhuchunping featuring characteristic 4000 pear shaped body coated with a pale green hue, 8.5"h $ 500 - 700 Chinese Yaozhou-type molded ceramic bowl, featuring lotus sprigs and fish reserves to 4001 the interior, 7.25"w $ 300 - 500 (lot of 3) Group of Chinese ceramics: consisting of a celadon glazed tripod censer, with a 4002 ribbed cylindrical body; a persimmon glazed bowl, molded with a peony; together with a marble glazed dish, largest: 7"w $ 400 - 600 Chinese Guan-type censer, with a flared rim and low slung body, the tan colored body 4003 with a network of crackles, flanked by a pair of shaped handles, 6.25"w $ 300 - 500 Chinese celadon glazed covered jar, in the form of a granary, with a thatched roof form lid 4004 and cylindrical body, 5.75"h $ 300 - 500 (lot of 6) Chinese assorted ceramics: three dishes and a Jun-type bowl; one Ge-type five 4005 stem vase, with five tubes encircling the central neck; together with a celadon arrow vase, 8.25"h $ 500 - 700 4006 Chinese porcelain vase, of rhombus section with notched edges, the pastel blue ground with flowers of the four seasons in bisque, base with apocryphal Qianlong mark, 8.25"h $ 300 - 500 Chinese underglazed blue porcelain brush pot, the cylindrical form featuring scholar 4007 official and beauties gathered in front of a pavilion, base with apocryphal Kangxi mark, 6"h $ 400 - 600 Chinese blue-and-white porcelain circular box, the lid molded with a dragon reserve on a 4008 blue ground,