Coping with Protracted Displacement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Traditions of Carpet Weaving in the Southern Regions of Uzbekistan

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- EPRA International Journal of Socio-Economic and Environmental Outlook (SEEO) ISSN: 2348-4101 Volume: 8 | Issue: 3| March 2021 | SJIF Impact Factor (2021): 7.426 | Journal DOI: 10.36713/epra0314 | Peer-Reviewed Journal THE TRADITIONS OF CARPET WEAVING IN THE SOUTHERN REGIONS OF UZBEKISTAN Davlatova Saodat Tilovberdiyevna Doctor of Science Of the National University of Uzbekistan, The Head of the «Applied Ethnology» laboratory Abdukodirov Sarvar Begimkulovich, Teacher of Jizzakh State Pedagogical University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan ANNOTATION In the article is enlightened local features of traditions of the Uzbek carpet weaving on examples of samples from southern regions (Kashkadarya and Surkhandarya regions) of Uzbekistan. Also, are shown distinctive features in the processes of preparing raw materials and weaving machines, including the dyeing process of yarns, and are also described types of carpets and their features. KEY WORDS: carpet weaving, craft, loom, types of carpets, wool, carpet products DISCUSSION At the end of the 19th century and at the Carpet weaving is a long developed rare beginning of the 20th century the main raw material type of textile, it has been continuing its traditions of carpet weaving was sheep wool. The carpet for ages[4]. Mainly women deal with carpet weaving weavers of the southern regions almost didn’t use the and they knit many household furnishings, felt rugs, wool brought from Russia. But, there is information felts, carpets and other carpet products. about that they used the products brought from Carpet weaving is basically tightly Afghanistan, Iran and Eastern Turkistan[14]. connected with livestock, it is developed in Andijan, On the carpets of Kashkadarya the Samarkand, Kashkadarya, Surkhandarya, Bukhara traditions of carpet weaving of desert livestock cities of Uzbekistan and lowlands of Amudarya and breeder tribes are seen. -

Pakistan's Future Policy Towards Afghanistan. a Look At

DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN’S FUTURE POLICY TOWARDS AFGHANISTAN A LOOK AT STRATEGIC DEPTH, MILITANT MOVEMENTS AND THE ROLE OF INDIA AND THE US Qandeel Siddique DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 © Copenhagen 2011, Qandeel Siddique and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: The Khyber Pass linking Pakistan and Afghanistan. © Luca Tettoni/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-455-7 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This publication is part of DIIS’s Defence and Security Studies project which is funded by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Defence. Qandeel Siddique, MSc, Research Assistant, DIIS [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Contents Abstract 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Pakistan–Afghanistan relations 12 3. Strategic depth and the ISI 18 4. Shift of jihad theatre from Kashmir to Afghanistan 22 5. The role of India 41 6. The role of the United States 52 7. Conclusion 58 Defence and Security Studies at DIIS 70 3 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Acronyms AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir ANP Awani National Party FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FDI Foreign Direct Investment FI Fidayeen Islam GHQ General Headquarters GoP Government -

Analysis of Pakistan's Policy Towards Afghan Refugees

• p- ISSN: 2521-2982 • e-ISSN: 2707-4587 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 • ISSN-L: 2521-2982 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 Muhammad Zubair* Muhammad Aqeel Khan† Muzamil Shah‡ Analysis of Pakistan’s Policy Towards Afghan Refugees: A Legal Perspective This article explores Pakistan’s policy towards Afghan refugees • Vol. IV, No. III (Summer 2019) Abstract since their arrival into Pakistan in 1979. As Pakistan has no • Pages: 28 – 38 refugee related law at national level nor is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol of 1967; but despite of all these obstacles it has welcomed the refugees from Afghanistan after the Russian aggression. During their Headings stay here in Pakistan, these refugees have faced various problems due to the non- • Introduction existence of the relevant laws and have been treated under the Foreigner’s Act • Pakistan's Policy Towards Refugees of 1946, which did not apply to them. What impact this absence of law has made and Immigrants on the lives of these Afghan refugees? Here various phases of their arrival into • Overview of Afghan Refugees' Pakistan as well as the shift in policies of the government of Pakistan have been Situation in Pakistan also discussed in brief. This article explores all these obstacles along with possible • Conclusion legal remedies. • References Key Words: Influx, Refugees, Registration, SAFRON and UNHCR. Introduction Refugees are generally casualties of human rights violations. What's more, as a general rule, the massive portion of the present refugees are probably going to endure a two-fold violation: the underlying infringement in their state of inception, which will more often than not underlie their flight to another state; and the dissent of a full assurance of their crucial rights and opportunities in the accepting state. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Market Issue DESIGN FOCUS DESIGN D’Aquino Carl

DESIGN FOCUS Carl D’Aquino WINTER 2018 NORS 2018 Market Issue ATLANTA LAS VEGAS SOUMAK JANUARY 10 - 14, 2018 JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 1, 2018 COLLECTION (CLOSED 1/13) WORLD MARKET CENTER, AMERICASMART 4-G14 BUILDING B, B-0455 WWW.KALATY.COM view the Entire Collection momeni.com/eringates ATLANTA MARKET LAS VEGAS MARKET 4-B-2 January 10-14, 2018 B-425 January 28-February 1, 2018 Invite your customers to experience island-inspired living at its fi nest through the refi ned yet casual Tommy Bahama area rug collection. ATLANTA 3-A-2 | LAS VEGAS C395 | OWRUGS.COM/TOMMY AreaMag_OW_FULL_TOMMY_Nov2017.indd 1 10/31/17 3:23 PM ta m ar ian www.tamarian.com The Hygge Collection. Coming this January. ATLANTA 4-D-2 | DALLAS C-506 | VEGAS B-480 winter 2018 8.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 12/4/17 2:54 PM Page 6 From the President’s Desk Dear Colleagues, also well received. As you may know, we recently lost an icon in the In October, there were also shows staged by rug industry, Mr. Nasser Rahmanan. Mr. manufacturers and their trade associations. They Rahmanan was a leader and forerunner in our invited all of our members to visit them with industry. He always dedicated his complimentary airfare and accom- time for the betterment of the rug modations. Lucille and I met off i- industry. As a past president of cials of each trade association to dis- ORIA, a friend and a mentor, he cuss marketing and promotions of will be missed. Please read the arti- their respective country’s rugs here cle “In Memoriam” of Mr. -

An Investigation and Comparison of Strength Against the Compressive

ISSN (Print) : 2319-8613 ISSN (Online) : 0975-4024 Behzad Nikandish et al. / International Journal of Engineering and Technology (IJET) An Investigation and Comparison of Strength against the Compressive loads (Static and Dynamic) in 4 Iranian, Chinese, Uzbek, and Turkmen Types of Silk Used in Iran’s Hand-woven Carpets Behzad Nikandish Master student of Carpet, Kashan University Gholamreza Saleh Alavi Corresponding author, Faculty member of Carpet Department, Kashan University Email: [email protected] Abstract: The silk yarns are mostly used in carpet’s piles. Among the important attributes of the yarns used in the carpet’s piles is the strength against the static and dynamic load. In the current study, three woven samples from each of the four types as Iranian, Chinese, Turkmen, and Uzbek silks were extracted and through the required tests, the above-mentioned attributes were investigated and compared for them. The results indicate that against the static loads, the Chinese silk has the highest strength, and the Uzbek and Iranian silks are next, with a narrow difference. The Turkmen is ranked last in terms of strength. Also, the Iranian silk did best in strength against the dynamic loads, and it had the highest strength, with the Turkmen, Chinese, and Uzbek silks being after it with a marginal difference. The current study is conducted by the use of documentary and laboratory methods. Keywords: Silk, hand-woven carpet, Strength against static load, Strength against the dynamic load. 1- Introduction: The silk yarns have been long used in the production of beautiful and precious fabrics. These yarns, due to their unique attributes, are being used in many other industries. -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Governance and Militancy in Pakistan's Kyber Agency

December 2011 1 Governance and Militancy in Pakistan’s Khyber Agency Mehlaqa Samdani Introduction and Background In mid-October 2011, thousands of families were fleeing Khyber, one of the seven tribal agencies in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), to refugee camps or relatives living outside of FATA. Their flight was in response to the announcement by the Pakistani military that it was undertaking a fresh round of operations against militant groups operating in the area. Militants have been active in Khyber (and FATA more generally) for several years. Some have used the area as a safe haven, resting between their own military operations in Afghanistan or other parts of Pakistan. Others have competed locally for influence by providing justice or security services, by decrying the ruling elite’s failure to provide these and other services to the local population, or by using force against those people the militants consider threatening or un-Islamic. The Pakistani military’s actions against militants in Khyber have already driven most of these nonstate groups out of the more populated areas and into Khyber’s remote Tirah Valley. But beyond that, the government of Pakistan has failed to implement most of the legal and political changes required to reform Khyber’s dysfunctional governance system to meet the needs of its residents. Khyber Agency is home to some half-million people, all of whom are ethnic Pashtuns from four major tribal groupings: Afridi, Shinwari, Mullagori, and Shalmani. It is also home to the historic Khyber Pass (to Afghanistan’s Nangarhar Province). Khyber Agency covers an area of 2,576 square kilometers, with Mohmand Agency to the north, the district of Peshawar to the east, Orakzai Agency to the south, and Kurram Agency to the west. -

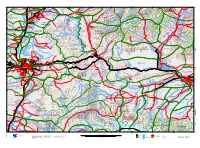

Afghanistan Topographic Maps with Background (PI42-07)

Sufikhel # # # # # # # # # # # ChayelGandawo Baladeh # Ashorkhel Khwaja-ghar Karak # Kashkha Kawdan Kotale Darrahe Kalan Dasht # Chaharmaghzdara # Eskenya # Zekryakhe# l Korank # # # # Zabikhel # # Qal'a Safed # Khwaja Ahmad # Matan # # # # Ofyane Sharif # # Abdibay # # # Koratas # Wayar # # # Margar Baladeh Walikhel # Tawachyan # Zaqumi# Tayqala Balaghel Qal'a Mirza # Tarang Sara # # Mangalpur Qala Faqirshah # # # # # # Aghorsang Gyawa-i-Payan # # # Darrahe Estama Charikar # # Darrah Kalan Mirkhankhel # # Dadokhel# # Ghazibikhel Dehe-Qadzi # Sedqabad(Qal'a Wazir) Kalawut # # Paytak Nilkhan Dolana Alikhel # Pasha'i Tauskhel # # # # # # # Dehe Babi Y Sherwani Bala # # # Gulghundi # Sayadan Jamchi # Angus # # Tarwari Lokakhel # # # # Jolayan Baladeh # Sharuk # # # # Y # Karezak Bagi Myanadeh # Khwaja Syarane Ulya Dashte Ofyan Bayane Pain Asorkhel Zwane # Dinarkhel Kuhnaqala # Dosti # # # Hazaraha # Sherwani Paya# n Pash'i# Hasankhankhel Goshadur # 69°00' # 10' Dehe Qadzi 20' # 30' 40' 50' 70°00' 10' # Sama2n0d' ur 70# °30' Mirkheli # Sharif Khel # # # iwuh # # Daba 35°00' # # # # 35°00' Zargaran # Qaracha Qal'eh-ye Naw # # Kayli # Pashgar # Ny# azi # Kalacha # Pasha'i # Kayl Daba # # # # # # Paryat Gamanduk # Sarkachah Jahan-nema # # Sadrkhel Yakhel Ba# ltukhel # # # Bebakasang # # # # # # Qoroghchi Badamali # # Qal'eh-ye Khwajaha Qal`eh-ye Khanjar Hosyankhankhel # Odormuk # Mayimashkamda # Sayad # # # # NIJRAB # # Khanaha-i-Gholamhaydar Topdara # Babakhel Kharoti Kundi # Woturu # # Tokhchi # # # Qal`eh-ye Khanjar Sabat Nawjoy # # # Dugran -

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad-settler conflict in Afghanistan today Dr. Antonio Giustozzi October 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Synthesis paper Nomad-settler conflict in Afghanistan today Dr. Antonio Giustozzi October 2019 Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-40-2 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1907 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research institute based in Kabul that was established in 2002 by the assistance of the international community in Afghanistan. AREU’s mission is to inform and influence policy and practice by conducting high-quality, policy relevant, evidence-based research and actively disseminating the results and promote a culture of research and learning. As the top think-tank in Afghanistan and number five in Central Asia according to the Global Go To Think Tank Index Report at the University of Pennsylvania, AREU achieves its mission by engaging with policy makers, civil society, researchers and academics to promote their use of AREU’s research-based publications and its library, strengthening their research capacity and creating opportunities for analysis, reflection and debate. AREU is governed by a Board of Directors comprised of representatives of donor organizations, embassies, the United Nations and other multilateral agencies, Afghan civil society and independent experts. -

Integrated Work Plan 1387 (1St April 08 - 31St March 09) Version 1.0

United Nations Mine Action Centre for Afghanistan MACA MAPA MINE ACTION PROGRAMME FOR AFGHANISTAN Integrated Work Plan 1387 (1st April 08 - 31st March 09) Version 1.0 ﻣﺮﮐﺰ ﻣﺎﻳﻦ ﭘﺎﮐﯽ ﻣﻠﻞ ﻣﺘﺤﺪ ﺑﺮاﯼ اﻓﻐﺎﻧﺴﺘﺎن (United Nations Mine Action Centre for Afghanistan (MACA House 95, Charahi-e-Zambaq, Wazir Akbar Khan ﺧﺎﻧﻪ 95، ﺳﺮﮎ ﺟﻴﻢ، ﭼﻬﺎراهﯽ زﻧﺒﻖ، وزﻳﺮ اﮐﺒﺮ ﺧﺎن P.O. Box: 520 Central Post Office Kabul – Afghanistan ﭘﺴﺖ ﺑﮑﺲ 520، ﭘﺴﺘﻪ ﺧﺎﻧﻪ ﻣﺮﮐﺰﯼ ﮐﺎﺑﻞ Tel: +93(0)70-043 447/+93(0)798-010 460 ﺗﻠﻴﻔﻮن: email: [email protected] +93(0)798-010 460/ +93(0)70-043 447 ﭘﺴﺖ اﻟﮑﺘﺮوﻧﻴﮏ: [email protected] Contents Page Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………...3 Mine & Explosive Remnants of War Contamination in Afghanistan…………………4 Mine Action Programme for Afghanistan……………………………………………….5 Mine & ERW Scope as of 1387 …………………………………………………………7 Priority Setting……………………………………………………………………………..7 Mine Action Strategic Framework……………………………………………………….8 Objective 1: Coordination, Transition & Capacity Building…………………………...8 Objective 2: Demining Operations………………………………………………………9 Detail of Priorities…………………………………………………………………………11 Quality Management……………………………………………………………………..13 Mine Detection Dog………………………………………………………………………13 Mechanical………………………………………………………………………………...14 EOD………………………………………………………………………………………..14 Medical…………………………………………………………………………………….15 1387 Integrated Work Plan Output……………………………………………………..16 Asset Allocation & Priorities……………………………………………………………..16 Regionalization……………………………………………………………………………17 Expansion of Community Based Demining Approach………………………………..18 Competitive Tendering -

SECOND-GENERATION AFGHANS in NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES from Mohajer to Hamwatan: Afghans Return Home

From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home Case Study Series SECOND-GENERATION AFGHANS IN NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home Mamiko Saito Funding for this research was December 2007 provided by the European Commission (EC) and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit i Second-Generation Afghans in Neighbouring Countries © 2007 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher, the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit. Permission can be obtained by emailing [email protected] or calling +93 799 608 548. ii Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit From mohajer to hamwatan: Afghans return home About the Author Mamiko Saito is the senior research officer on migration at AREU. She has been work- ing in Afghanistan and Pakistan since 2003, and has worked with Afghan refugees in Quetta and Peshawar. She holds a master’s degree in education and development studies from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation headquartered in Kabul. AREU’s mission is to conduct high-quality research that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively pro- motes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and facilitating reflection and debate. Fundamental to AREU’s vision is that its work should improve Afghan lives.