Afghanistan Opium Survey 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download at and Most in Hardcopy for Free from the AREU Office in Kabul

Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit Watching Brief Nomad Sedentarisation Processes in Afghanistan and Their Impact on Conflict Dr. Antonio Giustozzi September 2019 The information and views set out in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of AREU and European Union. Editor: Matthew Longmore ISBN: 978-9936-641-34-1 Front cover photo: AREU AREU Publication Code: 1905 E © 2019 This publication may be quoted, cited, or reproduced only for non-commercial purposes and provided that the source is acknowledged. The opinions expessed in this publication are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect that of AREU. Where this publication is reproduced, stored, or transmitted electronically, a link to AREU’s website (www.areu.org.af) should be provided. Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit 2019 Table of Contents About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit .................................................... II Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Past Experiences in Sedentarisation .......................................................................... 2 Sedentarisation Post-2001 ...................................................................................... 3 Drivers of Sedentarisation ......................................................................................... -

Update Conflict Displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013

Update conflict displacement Faryab Province 22 May 2013 Background On 22 April, Anti-Government Elements (AGE) launched a major attack in Qaysar district, making Faryab province one of their key targets of the spring offensive. The fighting later spread to Almar district of Faryab province and Ghormach of Badghis Province, displacing approximately 2,500 people. The attack in Qaysar was well organized, involving several hundred AGE fighters. According to Shah Farokh Shah, commander of 300 Afghan local policemen in Khoja Kinti, some of the insurgents were identified as ‘Chechens and Pakistani Taliban’1. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) has regained control of the Qaysar police checkpoints. The plan is to place 60 Afghan local policemen (ALPs) at the various checkpoints in the Khoja Kinti area. Quick Response Forces with 40 ALPs have already been posted. ANSF is regaining control in Ghormach district. Similar efforts are made in Almar and Pashtun Kot. Faryab OCCT has decided to replace ALP and ANP, originally coming from Almar district, with staff from other districts. Reportedly the original ALP and ANP forces have sided with the AGE. Security along the Shiberghan - Andkhoy road has improved. The new problem area is the Andkhoy - Maymana road part. 200 highway policemen are being recruited to secure the Maymana - Shibergan highway. According to local media reports the Taliban forces have not been defeated and they are still present in the area. There may be further displacement in view of the coming ANSF operations. Since the start of this operation on 22 April, UNAMA documented 18 civilian casualties in Qaysar district from ground engagements between AGEs and ANSF, IED incidents targeting ANP and targeted killings. -

Gouvernance Des Coopératives Agricoles Dans Une Économie En Reconstruction Après Conflit Armé : Le Cas De L’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf

Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruction après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan Mohammad Edris Raouf To cite this version: Mohammad Edris Raouf. Gouvernance des coopératives agricoles dans une économie en reconstruc- tion après conflit armé : le cas de l’Afghanistan. Gestion et management. Université Paul Valéry- Montpellier III, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018MON30092. tel-03038739 HAL Id: tel-03038739 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03038739 Submitted on 3 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ PAUL VALÉRY DE MONTPELLIER III ÉCOLE DOCTORALE ÉCONOMIE ET GESTION DE MONTPELLIER ED 231, LABORATOIRE ART- DEV (ACTEURS, RESSOURCES ET TERRITOIRES DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT), SUP-AGRO MONTPELLIER Gouvernanceou e a cedescoopéat des coopératives esag agricoles coesda dans su une eéco économie o ee en reconstruction après conflit armé, le cas de l’Afghanistan By: Mohammad Edris Raouf Under Direction of Mr. Cyrille Ferraton MCF -HDR en sciences économiques, Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, -

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

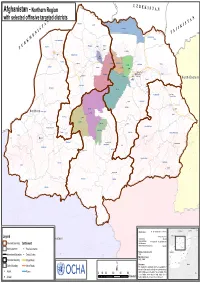

Download Map (PDF | 2.37

in te rn a tio n U a Z Khamyab l B Afghanistan - Northern Region E KIS T A N Qarqin with selected offinsive targeted districts A N Shortepa T N Kham Ab l a Qarqin n S o A i I t a n K T Shortepa r e t n S i JI I Kaldar N T A E Sharak Hairatan M Kaldar K Khani Chahar Bagh R Mardyan U Qurghan Mangajek Mangajik T Mardyan Dawlatabad Khwaja Du Koh Aqcha Aqcha Andkhoy Chahar Bolak Khwaja Du Koh Fayzabad Khulm Balkh Nahri Shahi Qaramqol Khaniqa Char Bolak Balkh Mazari Sharif Fayzabad Mazari Sharif Khulm Shibirghan Chimtal Dihdadi Nahri Shahi NorthNorth EasternEastern Dihdadi Marmul Shibirghan Marmul Dawlatabad Chimtal Char Kint Feroz Nakhchir Hazrati Sultan Hazrati Sultan Sholgara Chahar Kint Sholgara Sari Pul Aybak NorthernShirin Tagab Northern Sari Pul Aybak Qush Tepa Sayyad Sayyad Sozma Qala Kishindih Dara-I-Sufi Payin Khwaja Sabz Posh Sozma Qala Darzab Darzab Kishindih Khuram Wa Sarbagh Almar Dara-i-Suf Maymana Bilchiragh Sangcharak (Tukzar) Khuram Wa Sarbagh Sangcharak Zari Pashtun Kot Gosfandi Kohistanat (Pasni) Dara-I-Sufi Bala Gurziwan Ruyi Du Ab Qaysar Ruyi Du Ab Balkhab(Tarkhoj) Kohistanat Balkhab Kohistan Kyrgyzstan China Uzbekistan Tajikistan Map Doc Name: A1_lnd_eastern_admin_28112010 Legend CapitalCapital28 November 2010 Turkmenistan Jawzjan Badakhshan Creation Date: Kunduz Western WGS84 Takhar Western Balkh Projection/Datum: http://ochaonline.un.org/afghanistan Faryab Samangan Baghlan Provincial Boundary Settlement Web Resources: Sari Pul Nuristan Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:640,908 Badghis Bamyan Parwan Kunar Kabul !! Maydan -

Kandahar Survey Report

Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report February 1996 AREA Office 17 - E Abdara Road UfTow Peshawar, Pakistan Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan I AREA Kandahar Survey Report Prepared by Eng. Yama and Eng. S. Lutfullah Sayed ·• _ ....... "' Content - Introduction ................................. 1 General information on Kandahar: - Summery ........................... 2 - History ........................... 3 - Political situation ............... 5 - Economic .......................... 5 - Population ........................ 6 · - Shelter ..................................... 7 -Cost of labor and construction material ..... 13 -Construction of school buildings ............ 14 -Construction of clinic buildings ............ 20 - Miscellaneous: - SWABAC ............................ 2 4 -Cost of food stuff ................. 24 - House rent· ........................ 2 5 - Travel to Kanadahar ............... 25 Technical recommendation .~ ................. ; .. 26 Introduction: Agency for Rehabilitation & Energy-conservation in Afghanistan/ AREA intends to undertake some rehabilitation activities in the Kandahar province. In order to properly formulate the project proposals which AREA intends to submit to EC for funding consideration, a general survey of the province has been conducted at the end of Feb. 1996. In line with this objective, two senior staff members of AREA traveled to Kandahar and collect the required information on various aspects of the province. -

Child Friendly School Baseline Survey

BASELINE SURVEY OF CHILD-FRIENDLY SCHOOLS IN TEN PROVINCES OF AFGHANISTAN REPORT submitted to UNICEF Afghanistan 8 March 2014 Society for Sustainable Development of Afghanistan House No. 2, Street No. 1, Karti Mamorin, Kabul, Afghanistan +93 9470008400 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 STUDY MODIFICATIONS ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3 STUDY DETAILS ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................... 6 2. APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................ 7 2.1 APPROACH .......................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................ 8 3. TRAINING OF FIELD STAFF ..................................................................................... 14 3.1 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ -

AFGHANISTAN: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) Western Region (October to December 2018)

AFGHANISTAN: Humanitarian Operational Presence (3W) Western Region (October to December 2018) All Clusters Ghormach 1 Number of organisations reported Bala per district Murghab 4 1 - 2 Gulran Kushk-e-Kuhna 1 3 - 10 2 Muqur Badghis Ab Charsadra Kushk 6 11 - 20 Kamari 7 > 20 Kohsan 5 5 Jawand 9 Qadis 2 No organisation reported Qala-e-Naw 3 Injil 15 Feroz Koh Karukh Lal Wa 25 5 Dawlatyar 8 Sarjangal Hirat Hirat 5 Obe Chisht-e-Sharif 5 28 2 Ghoryan Pashtun 2 Shahrak 3 Guzara Zarghun Zindajan 5 Ghor 7 11 2 Tolak DoLayna 4 6 Farsi Adraskan 2 3 Saghar Pasaband 1 1 Taywarah 2 Shindand 1 Pur Chaman Khak-e-Safed 1 1 Anar Dara Bala Buluk 2 2 Qala-e-Kah Pushtrod Farah Gulistan 1 1 1 Farah Kabul Shibkoh 9 Bakwa 2 1 Lash-e-Juwayn 2 46 organisations Delivering humanitarian services in October, November and December 2018. Emergency Shelter and Non-Food Items Food Security Health 1 2 2 1 1 3 1 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 1 2 3 5 2 2 1 3 1 1 1 3 1 8 5 4 2 3 1 3 2 2 3 3 4 1 1 1 8 2 4 8 2 1 1 6 1 2 3 1 5 1 2 4 5 1 2 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 2 1 2 1 1 1 3 2 2 1 2 13 organisations 19 organisations 6 organisations Nutrition Protection Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 1 1 1 1 4 1 2 2 2 4 7 1 1 2 1 1 6 1 6 9 3 1 4 1 3 1 1 1 1 16 2 1 3 3 2 1 2 2 2 5 1 20 1 1 1 2 6 2 1 1 1 1 5 3 10 organisations 26 organisations 10 organisations Operational Presence is defined as: Organisations with a physical presence on the ground and active in delivering humanitarian assistance in the districts during October, November and December 2018. -

1 USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive

USIP –ADST Afghan Experience Project Interviwe #1 Executive Summary The interviewee is a Farsi speaker and retired FSO who has had prior Afghan experience, including working with refugees during the period the Taliban was fighting to take over the country in 1995. He returned to Kabul in 2002 as chief of the political section, although retired, for seven months. He returned in 2003 and worked at the U.S. civil affairs mission in Herat for 6 months. He came back later in 2003 to Afghanistan working for the Asia Foundation. He worked on a PRT for approximately three months in late 2004 in Herat. The American presence was minimal when he got there. Security was excellent and the local warlord, Ismael Khan, was using revenues he siphoned from customs houses into development projects. Shortly after subject arrived in Herat, Khan was ousted in a brief battle by forces loyal to Kabul and with the threat of unrest U.S. forces were increased in the area. Our subject suggested to Khan that he make peace with the Kabul government, and he did, perhaps in part on the advice of subject. The Herat PRT had about one hundred American uniformed troops with three civilians, State, AID, Agriculture. Subject was the political advisor to the civil affairs staff, a reserve unit from Minnesota. But much of their work was soon taken over or undercut by the U.S. military task force commander brought in in response to the ouster of Khan. According to subject, the task force commander in the region saw himself as the political expert. -

Afghanistan | Agricultural Livelihoods and Food Security in the Context of COVID-19: Monitoring Report – August 2021

AFGHANISTAN Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19 Monitoring report August 2021 AFGHANISTAN Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19 Monitoring report August 2021 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 REQUIRED CITATION FAO. 2021. Afghanistan | Agricultural livelihoods and food security in the context of COVID-19: Monitoring report – August 2021. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb6398en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN 978-92-5-134842-0 © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

(2): Delivering Public Services in Insurgency-Affected Obeh District of Herat Province

One Land, Two Rules (2): Delivering public services in insurgency-affected Obeh district of Herat province Author : S Reza Kazemi Published: 9 December 2018 Downloaded: 8 December 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-admin/post.php The matter of who governs the district of Obeh in the east of Herat province is complicated: control of the district is divided between the Afghan government and the Taleban, and shifts in unpredictable ways. The inhabitants of the district, usually via the mediation of elders, have had to learn how to deal with both sides. The dual nature of authority in Obeh is exemplified by public service delivery; it is always financed through and administered by the Afghan state but, in areas under Taleban control, it is the insurgents who supervise and monitor delivery. In this, the first of a series of case studies looking at the delivery of services in districts over which the Taleban have control or influence, AAN researcher Said Reza Kazemi investigates the provision of governance and security, education, health, electricity, telecommunications and development projects, and unpacks a dual form of governance. Service Delivery in Insurgent-Affected Areas is a joint research project by the Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) and the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). For the methodology and literature review, see here. Obeh district: the context 1 / 22 Approximately 100 km to the east of Herat city, linked by mainly non-asphalted roads; mountainous, cut through by fertile Harirud River valley