Peer Review Comments, CARB Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let Me Just Add That While the Piece in Newsweek Is Extremely Annoying

From: Michael Oppenheimer To: Eric Steig; Stephen H Schneider Cc: Gabi Hegerl; Mark B Boslough; [email protected]; Thomas Crowley; Dr. Krishna AchutaRao; Myles Allen; Natalia Andronova; Tim C Atkinson; Rick Anthes; Caspar Ammann; David C. Bader; Tim Barnett; Eric Barron; Graham" "Bench; Pat Berge; George Boer; Celine J. W. Bonfils; James A." "Bono; James Boyle; Ray Bradley; Robin Bravender; Keith Briffa; Wolfgang Brueggemann; Lisa Butler; Ken Caldeira; Peter Caldwell; Dan Cayan; Peter U. Clark; Amy Clement; Nancy Cole; William Collins; Tina Conrad; Curtis Covey; birte dar; Davies Trevor Prof; Jay Davis; Tomas Diaz De La Rubia; Andrew Dessler; Michael" "Dettinger; Phil Duffy; Paul J." "Ehlenbach; Kerry Emanuel; James Estes; Veronika" "Eyring; David Fahey; Chris Field; Peter Foukal; Melissa Free; Julio Friedmann; Bill Fulkerson; Inez Fung; Jeff Garberson; PETER GENT; Nathan Gillett; peter gleckler; Bill Goldstein; Hal Graboske; Tom Guilderson; Leopold Haimberger; Alex Hall; James Hansen; harvey; Klaus Hasselmann; Susan Joy Hassol; Isaac Held; Bob Hirschfeld; Jeremy Hobbs; Dr. Elisabeth A. Holland; Greg Holland; Brian Hoskins; mhughes; James Hurrell; Ken Jackson; c jakob; Gardar Johannesson; Philip D. Jones; Helen Kang; Thomas R Karl; David Karoly; Jeffrey Kiehl; Steve Klein; Knutti Reto; John Lanzante; [email protected]; Ron Lehman; John lewis; Steven A. "Lloyd (GSFC-610.2)[R S INFORMATION SYSTEMS INC]"; Jane Long; Janice Lough; mann; [email protected]; Linda Mearns; carl mears; Jerry Meehl; Jerry Melillo; George Miller; Norman Miller; Art Mirin; John FB" "Mitchell; Phil Mote; Neville Nicholls; Gerald R. North; Astrid E.J. Ogilvie; Stephanie Ohshita; Tim Osborn; Stu" "Ostro; j palutikof; Joyce Penner; Thomas C Peterson; Tom Phillips; David Pierce; [email protected]; V. -

What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD

2018 RELEASE THE UNDERSTATEMENT OF EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK BY DAVID SPRATT & IAN DUNLOP | FOREWORD BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER BREAKTHROUGHONLINE.ORG.AU Published by Breakthrough, National Centre for Climate Restoration, Melbourne, Australia. First published September 2017. Revised and updated August 2018. CONTENTS FOREWORD 02 INTRODUCTION 04 RISK UNDERSTATEMENT EXCESSIVE CAUTION 08 THINKING THE UNTHINKABLE 09 THE UNDERESTIMATION OF RISK 10 EXISTENTIAL RISK TO HUMAN CIVILISATION 13 PUBLIC SECTOR DUTY OF CARE ON CLIMATE RISK 15 SCIENTIFIC UNDERSTATEMENT CLIMATE MODELS 18 TIPPING POINTS 21 CLIMATE SENSITIVITY 22 CARBON BUDGETS 24 PERMAFROST AND THE CARBON CYCLE 25 ARCTIC SEA ICE 27 POLAR ICE-MASS LOSS 28 SEA-LEVEL RISE 30 POLITICAL UNDERSTATEMENT POLITICISATION 34 GOALS ABANDONED 36 A FAILURE OF IMAGINATION 38 ADDRESSING EXISTENTIAL CLIMATE RISK 39 SUMMARY 40 What Lies Beneath 2 FOREWORD What Lies Beneath is an important report. It does not deliver new facts and figures, but instead provides a new perspective on the existential risks associated with anthropogenic global warming. It is the critical overview of well-informed intellectuals who sit outside the climate-science community which has developed over the last fifty years. All such expert communities are prone to what the French call deformation professionelle and the German betriebsblindheit. Expressed in plain English, experts tend to establish a peer world-view which becomes ever more rigid and focussed. Yet the crucial insights regarding the issue in question may lurk at the fringes, as BY HANS JOACHIM SCHELLNHUBER this report suggests. This is particularly true when Hans Joachim Schellnhuber is a professor of theoretical the issue is the very survival of our civilisation, physics specialising in complex systems and nonlinearity, where conventional means of analysis may become founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate useless. -

YALE Environmental NEWS

yale environmental NEWS Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, and Yale Institute for Biospheric Studies fall/winter 2009–2010 · vol. 15, no. 1 Peabody Curator Awarded MacArthur “Genius” Grant page 12 KROON HALL RECEIVES DESIGN AWARDS Kroon Hall, the Yale School of Foresty & Environmental Studies’ new ultra- green home, captured two awards this fall for “compelling” design from the American Institute of Architects. “The way the building performs is essential contrast with the brownstone and maroon moment a visitor enters the building at ground to this beautiful, cathedral-like structure,” the brick of other Science Hill buildings. Glass level, the long open stairway carries the eye up jurors noted. “Part of its performance is the facades on the building’s eastern and western toward the high barrel-vaulted ceiling and the creation of a destination on the campus. The ends are covered by Douglas fi r louvers, which big window high up on the third fl oor, with its long walls of its idiosyncratic, barn-like form are positioned to defl ect unwanted heat and view into Sachem’s Wood. defi ne this compelling building.” glare. The building’s tall, thin shape, combined Opened in January 2009, the 58,200- Designed by Hopkins Architects of Great with the glass facades, enables daylight to pro- square-foot Kroon Hall is designed to use Britain, in partnership with Connecticut-based vide much of the interior’s illumination. And 50% less energy and emit 62% less carbon Centerbrook Architects and Planners, the the rounded line of the standing seam metal dioxide than a comparably sized modern aca- $33.5 million Kroon Hall received an Honor roof echoes the rolling whaleback roofl ine of demic building. -

Atmospheric Circulation Newsletter of the University of Washington Atmospheric Sciences Department

Autumn 2017 Atmospheric Circulation Newsletter of the University of Washington Atmospheric Sciences Department Studying the effects of Southern African biomass burning on clouds and climate: The ORACLES mission by Professor Robert Wood, Michael Diamond, & Sarah Doherty iny aerosol particles, emitted by Fires, mainly associated with dry season Teverything from tailpipes to trees, float agricultural burning on African savannas, above us reflecting sunlight, seeding clouds and generate smoke, a chemical soup that absorbing solar heat. How exactly this happens includes a large quantity of tiny aerosol – and how it might change in the future particles. This smoke rises high in – is one of the biggest uncertainties the atmosphere driven by strong in how humans are influencing surface heating and then is climate. blown west off the coast; it In September 2016, three then subsides down toward University of Washington the cloud layer over the scientists took part in a southeastern Atlantic large NASA field campaign, Ocean. The interaction Observations of Aerosols between air moisture and Above Clouds and their smoke pollution is complex Interactions, or ORACLES, and not well understood. that is flying research planes Southern Africa produces around clouds off the west coast almost a third of the Earth’s of southern Africa to see how smoke biomass burning aerosol particles, particles and clouds interact. yet the fate of these particles and their ORACLES is a five year program, with influence on regional and global climate is three month-long aircraft field studies, and is poorly represented in climate models. led by Dr. Jens Redemann from NASA Ames The ORACLES experiment is providing Research Center in California. -

2003 Annual Report MBLWHOI Library Woods Hole, MA 02543

WHOI Contributions to the Scientific Literature 2003 Annual Report MBLWHOI Library Woods Hole, MA 02543 2003 Publications Received as of January 1, 2004 Entries are listed by department. Where appropriate, the Institution Contribution number appears at the end of the entry. Earlier publications not listed in prior Annual Reports are listed here. Compiled by Ann Devenish; edited by Colleen Hurter. Reprint requests should be directed to the journal of publication, by contacting one of the authors directly or through MBL/WHOI Interlibrary Loan. Note: Access to online articles may be limited to the Woods Hole scientific community Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Abbot, P., S. Celuzza, I. Dyer, B. Gomes, J. Fulford, J. Lynch, G. Gawarkiewicz, and D. Volak. Effects of Korean littoral environment on acoustic propagation. IEEE J.Oceanic Eng., 26:266-284, 2001. Anderson, Erik J., Alexandra Techet, Wade R. McGillis, Mark A. Grosenbaugh, and Michael S. Triantafyllou. Visualization and analysis of boundary layer flow in live and robotic fish. In: Turbulence and Shear Flow Phenomena--1 : First International Symposium, September 12-15, 1999, Santa Barbara, California. Sanjoy Banerjee and John K. Eaton, eds. New York: Begell House, :945-949, 1999. Badiey, M., Y. Mu, J. Lynch, J. Apel, and S. Wolf. Temporal and azimuthal dependence of sound propagation in shallow water with internal waves. IEEE J.Oceanic Eng., 27:117-129, 2002. Baldwin, K. C., J. D. Irish, B. Celikkol, M. R. Swift, D. Fredriksson, I. Tsukrov, and Michael Chambers. Open ocean aquaculture engineering. Oceans '02, :111-120, 2002. - 1 - Ballard, Robert D., Lawrence E. Stager, Daniel Master, Dana Yoerger, David Mindell, Louis L. -

Significant Papers from the First 50 Years of the Boulder Labs

B 0 U l 0 I R LABORATORIES u.s. Depan:ment • "'.."'c:omn-..""""....... 1954 - 2004 NISTIR 6618 and NTIA SP-04-416 Significant Papers from the First 50 Years of the Boulder Labs Edited by M.E. DeWeese M.A. Luebs H.L. McCullough u.s. Department of Commerce Boulder Laboratories NotionallnstitlJte of Standards and Technology Notional Oc::eonic and Atmospheric Mministration Notional Telecommunications and Informofion Administration NISTIR 6618 and NTIA SP-04-416 Significant Papers from the First 50 Years of the Boulder Labs Edited by M.E. DeWeese, NIST M.A. Luebs, NTIA H.L. McCullough, NOAA Sponsored by National Institute of Standards and Technology National Telecommunications and Information Administration National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Boulder, Colorado August 2004 U.S. Department of Commerce Donald L. Evans, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Arden L. Bement, Jr., Director National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr., Undersecretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and NOAA Administrator National Telecommunications and Information Administration Michael D. Gallagher, Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information ii Acronym Definitions CEL Cryogenic Engineering Laboratory CIRES Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences CRPL Central Radio Propagation Laboratory CU University of Colorado DOC Department of Commerce EDS Environmental Data Service ERL ESSA Research Laboratory ESSA Environmental Science Services Administration ITS Institute for -

23Rd Annual Interdisciplinary Symposium

T o m a l e s B a y 23rd Annual Interdisciplinary Symposium Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science 468 Donner Lab June 7-9, 2019 Berkeley, CA 94720-5190 U n i v e r s i t y o f C a l i f o r n i a , B e r k e l e y Email: [email protected] http://miller.berkeley.edu Phone: 510-642-4088 THE MILLER INSTITUTE A BRIEF HISTORY NAME INSTITUTION DEPARTMENT EMAIL ADDRESS UC BERKELEY MOLECULAR & CELL [email protected] LEMON, CHRISTOPHER BIOLOGY The Miller Institute was established in 1955 after Adolph C. Miller and his wife, LU, JESSICA UC BERKELEY ASTRONOMY [email protected] Mary Sprague Miller donated just over $5 million dollars to the University. It was their wish that the donation be used to establish an institute “dedicated to the en- MANGA, UC BERKELEY EARTH & PLANETARY [email protected] couragement of creative thought and conduct of pure science.” The gift was made MICHAEL SCIENCE in 1943 but remained anonymous until after the death of the Millers. MARTELL, JEFF UNIV OF WISCONSIN CHEMISTRY [email protected] Adolph Miller was born in San Francisco on January 7, 1866. He entered UC in 1883 and was active throughout his CAL years. After graduation he went to Har- MERCHANT, UC BERKELEY MOLECULAR & CELL [email protected] vard for Graduate School and then for additional study in Paris and Munich. He SABEEHA BIOLOGY returned to the United States and taught Economics at Harvard until he was ap- MEYER, UC BERKELEY MOLECULAR & CELL [email protected] pointed Assistant Professor of Political Science in Berkeley in 1890. -

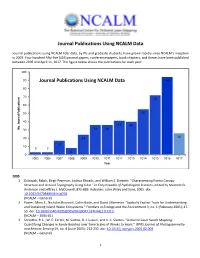

Journal Publications Using NCALM Data

Journal Publications Using NCALM Data Journal publications using NCALM lidar data, by PIs and graduate students, have grown rapidly since NCALM’s inception in 2003. Four hundred fifty-five (455) journal papers, conference papers, book chapters, and theses have been published between 2005 and April 11, 2017. The figure below shows the publications for each year: 100 90 Journal Publications Using NCALM Data 94 80 70 72 60 50 55 40 41 40 No. Journal Publications No. Journal 30 36 36 26 20 24 17 10 3 3 8 0 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Year 2005 1. Dubayah, Ralph, Birgit Peterson, Joshua Rhoads, and William E. Dietrich. “Characterizing Forest Canopy Structure and Ground Topography Using Lidar.” in Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences, edited by Malcolm G. Anderson and Jeffrey J. McDonnell, 875-886. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2005. doi: 10.1002/0470848944.hsa058. (NCALM – General) 2. Power, Mary E., Nicholas Brozović, Collin Bode, and David Zilberman. “Spatially Explicit Tools for Understanding and Sustaining Inland Water Ecosystems.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 3, no. 1 (February 2005): 47- 55. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0047:SETFUA]2.0.CO;2. (NCALM – 2004-01) 3. Shrestha, R. L., W. E. Carter, M. Sartori, B. J. Luzum, and K. C. Slatton. “Airborne Laser Swath Mapping: Quantifying Changes in Sandy Beaches over Time Scales of Weeks to Years.” ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 59, no. 4 (June 2005): 222-232. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2005.02.009. (NCALM – General) 1 2006 1. -

DRONES TAKE EARTH MONITORING to NEW HEIGHTS Thank You to Our 2015 Supporters Circle Donors*

VOL. 96 • NO. 19 • 15 OCT 2015 A Civil War–Era Painting of the Aurora Borealis What Darkens the Greenland Ice Sheet? Earth & Space Science News Dunes’ Importance on Planetary Surfaces DRONES TAKE EARTH MONITORING TO NEW HEIGHTS Thank You to Our 2015 Supporters Circle Donors* The leadership of AGU would like to thank all individuals who have made contributions of $100–$249 to AGU in 2015. Without your support many of AGU’s scholarships, grants, and other programs would not be possible. Lucy H. Adams Timothy H. Dixon Shijun Jiang Robyn M. Millan Ruth M. Skoug Thomas C. Adang James Francis Dolan Keith W. Jones Gretchen R. Miller Olav Slaymaker Jay James Ague James A. Doutt Donna M. Jurdy Ron L. Miller Rudy L. Slingerland M Joan Alexander Laurie Schuur Duncan Hiroo Kanamori Eberhard Moebius David Miles Smith Robert J. Alexander Elizabeth E. Ebert David M. Karl David W. Mogk Roger W. Smith Michael F. Allen Cynthia J. Ebinger Garry D. Karner Luisa T. Molina Joseph R. Smyth Donald E. Anderson Jr. Gary D. Egbert Peter B. Kelemen Steven Morley Adam H. Sobel James G. Anderson Anne E. Egger Michael Maier Keller L. J. Patrick Muffler Wim Spakman Karl Arnold Anderson Cheryl Enderlein Deborah S. Kelley Richard J. Murnane S. Spampinato Kenneth Argyle Sonia Esperanca Kathryn A. Kelly Craig S. Nelson Raymond C. Staley Marcelo Assumpcao Robert L. Evans Jack D. Kerns Eliza S. Nemser Rob Stoll II Roni Avissar Benjamin L. Everitt David W. Kicklighter Fred C. Newman George T. Stone Michael R. Babcock David W. Fahey Toshiaki Kikuchi Bart Nijssen Robert J. -

MAA FOCUS March 2008

MAA FOCUS March 2008 MAA FOCUS is published by the Mathematical Association of America in January, February, March, April, May/June, MAA FOCUS August/September, October, November, and December. Volume 28 Issue 3 Editor: Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College; [email protected] Inside Managing Editor: Carol Baxter, MAA [email protected] 4 Halmos Endowment Fund for the Carriage House Senior Writer: Harry Waldman, MAA By Gerald L. Alexanderson [email protected] Please address advertising inquiries to: 6 An Online Registration System for Section Meetings [email protected] By G. Jay Kerns, Jonathan Duran, Thomas E. Price, and D. P. Story President: Joseph Gallian 8 Teaching Time Savers: Using Preview Problems to Get Ahead of the Syllabus First Vice President: Elizabeth Mayfield, Second Vice President: Daniel J. Teague, By Marion Deutsche Cohen Secretary: Associate Martha J. Siegel, 9 Funding Available for Students Going to MathFest Secretary: James J. Tattersall, Treasurer: John W. Kenelly By Robert W. Vallin Executive Director: Tina H. Straley 10 Project NExT Reaches 1000 Fellows Director of Publications for Journals and 11 Developing Mathematical Habits of Mind Communications: Ivars Peterson By Annie Selden and Kien Lim MAA FOCUS Editorial Board: Donald J. Albers; Robert Bradley; Joseph Gallian; 12 Robert P. Balles Awards for IMO Team Participants Jacqueline Giles; Colm Mulcahy; Michael By Stephen Dunbar Orrison; Peter Renz; Sharon Cutler Ross; An- nie Selden; Hortensia Soto-Johnson; Peter 13 Undergraduates Win Awards at San Diego Stanek; Ravi Vakil. By Joe Gallian Letters to the editor should be addressed to Fernando Gouvêa, Colby College, Dept. of 14 Mathematicians Recruited for Climate Change Research Mathematics, Waterville, ME 04901, or by By Pat Kenschaft email to [email protected]. -

Focus the Nation, UC Berkeley

Speaker Bios for Focus the Nation, UC Berkeley January 31, 2008, International House 9 am – 10:15 am Welcome Nathan Brostrom, Vice Chancellor-Administration, UC Berkeley Vice Chancellor-Administration Nathan Brostrom joined the University of California, Berkeley leadership team on March 1, 2006. His position combines the duties of two previous vice chancellors, one in business and administrative services and one in budget and finance. As Vice Chancellor -- Administration, he is responsible for advising the Chancellor and the Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost on all budget and resource management, health and human services, and fiscal planning matters, both operating and capital. He is responsible for managing the campus's annual operating budget of more than $1.3 billion and he is responsible for a division that is the largest provider of services to campus staff and a significant provider of services to UC Berkeley students. 9 am to 10:15 The Future of the Planet: 2007 Nobel Peace Prize to IPCC Inez Fung, Professor of Atmospheric Science, ESPM. Co-Director of the Berkeley Institute of the Environment A principal research activity of Inez Fung is the carbon dioxide cycle. Fung’s lab uses details of the atmospheric CO2 distribution (e.g. the difference in hemispheric loading, the changes in the seasonal amplitude over time), together with atmospheric transport models to deduce the location of the carbon sink. Fung hypothesizes that the terrestrial biosphere of the northern hemisphere may be as important as the oceans as a repository for anthropogenic CO2. Another research focus is the dust cycle. Fine dust particles lofted from arid surfaces are transported long distances. -

1 Chapter 7: Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System And

First Order Draft Chapter 7 IPCC WG1 Fourth Assessment Report 1 2 Chapter 7: Couplings Between Changes in the Climate System and Biogeochemistry 3 4 Coordinating Lead Authors: Guy Brasseur, Kenneth Denman 5 6 Lead Authors: Amnat Chidthaisong, Philippe Ciais, Peter Cox, Robert Dickinson, Didier Hauglustaine, 7 Christoph Heinze, Elisabeth Holland, Daniel Jacob, Ulrike Lohmann, Srikanthan Ramachandran, Pedro 8 Leite da Silva Diaz, Steven Wofsy, Xiaoye Zhang 9 10 Contributing Authors: David Archer, V. Arora, John Austin, D. Baker, Joe Berry, Gordon Bonan, Philippe 11 Bousquet, Deborah Clark, V. Eyring, Johann Feichter, Pierre Friedlingstein, Inez Fung, Sandro Fuzzi, 12 Sunling Gong, Alex Guenther, Ann Henderson-Sellers, Andy Jones, Bernd Kärcher, Mikio Kawamiya, 13 Yadvinder Malhi, K. Masarie, Surabi Menon, J. Miller, P. Peylin, A. Pitman, Johannes Quaas, P. Rayner, 14 Ulf Riebesell, C. Rödenbeck, Leon Rotstayn, Nigel Roulet, Chris Sabine, Martin Schultz, Michael Schulz, 15 Will Steffen, Steve Schwartz, J. Lee-Taylor, Yuhong Tian, Oliver Wild, Liming Zhou. 16 17 Review Editors: Kansri Boonpragob, Martin Heimann, Mario Molina 18 19 Date of Draft: 12 August 2005 20 21 Notes: This is the TSU compiled version 22 23 24 Table of Contents 25 26 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 27 7.1 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................................