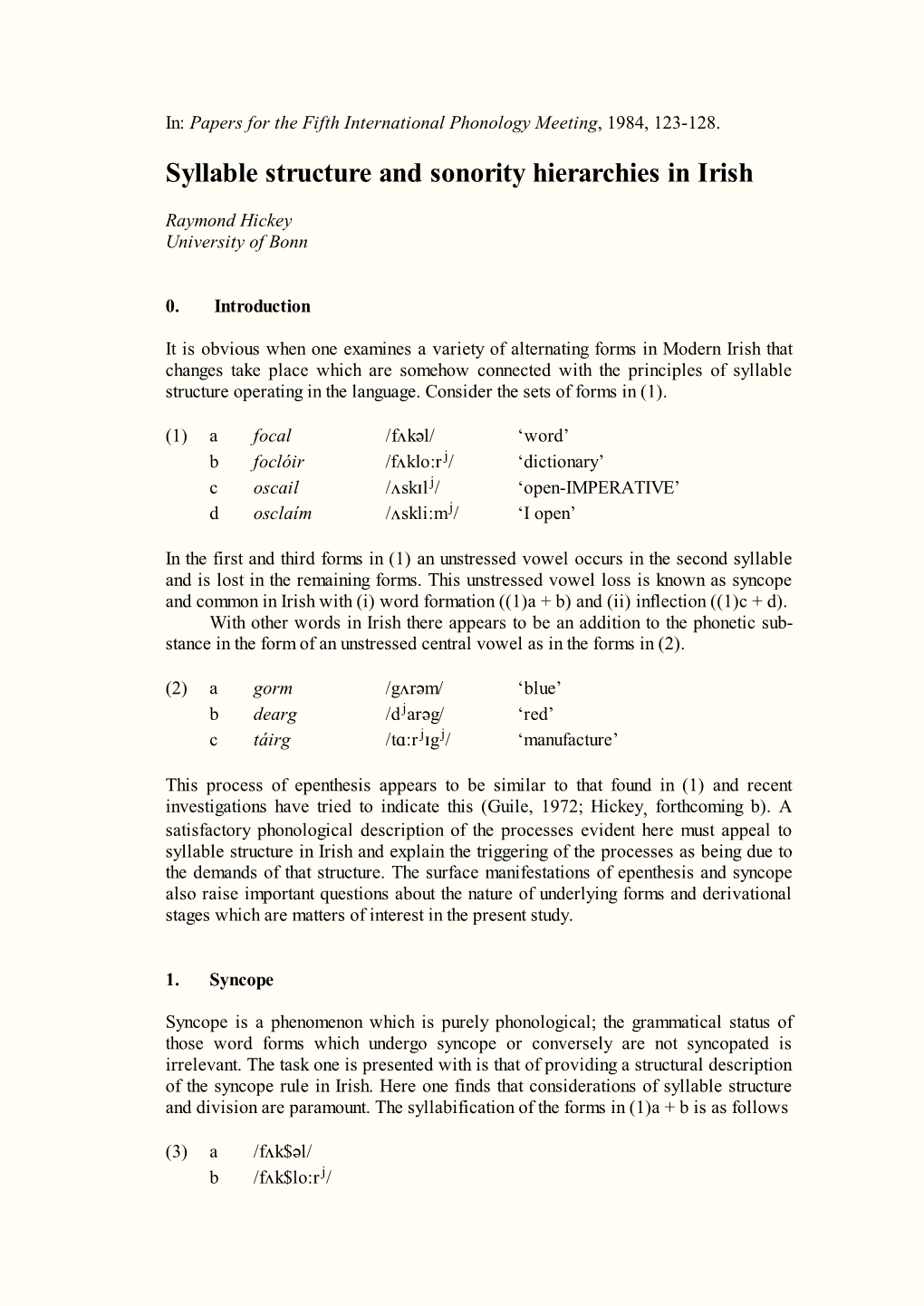

Syllable Structure and Sonority Hierarchies in Irish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Irish Spelling

Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey i © Stenson and Hickey 2018 ii Acknowledgements The preparation of this publication was supported by a grant from An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta, and we wish to express our sincere thanks to COGG, and to Muireann Ní Mhóráin and Pól Ó Cainín in particular. We acknowledge most gratefully the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship scheme for enabling this collaboration through its funding of an Incoming International Fellowship to the first author, and to UCD School of Psychology for hosting her as an incoming fellow and later an as Adjunct Professor. We also thank the Fulbright Foundation for the Fellowship they awarded to Prof. Stenson prior to the Marie Curie fellowship. Most of all, we thank the educators at first, second and third level who shared their experience and expertise with us in the research from which we draw in this publication. We benefitted significantly from input from many sources, not all of whom can be named here. Firstly, we wish to thank most sincerely all of the participants in our qualitative study interviews, who generously shared their time and expertise with us, and those in the schools that welcomed us to their classrooms and facilitated observation and interviews. We also wish to thank the participants at many conferences, seminars and presentations, particularly those in Bangor, Berlin, Brighton, Hamilton and Ottawa, as well as those in several educational institutions in Ireland who offered comments and suggestions. -

Initial Consonant Mutation in Modern Irish: a Synchronic and Diachronic Analysis Janine Fay Robinson San Jose State University

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2015 Initial Consonant Mutation in Modern Irish: A Synchronic and Diachronic Analysis Janine Fay Robinson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Robinson, Janine Fay, "Initial Consonant Mutation in Modern Irish: A Synchronic and Diachronic Analysis" (2015). Master's Theses. 4556. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.f5ad-sep5 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INITIAL CONSONANT MUTATION IN MODERN IRISH: A SYNCHRONIC AND DIACHRONIC ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Linguistics and Language Development San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Janine F. Robinson May 2015 © 2015 Janine F. Robinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled INITIAL CONSONANT MUTATION IN MODERN IRISH: A SYNCHRONIC AND DIACHRONIC ANALYSIS by Janine F. Robinson APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 Dr. Daniel Silverman Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Soteria Svorou Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Kenneth VanBik Department of Linguistics and Language Development iii ABSTRACT INITIAL CONSONANT MUTATION IN MODERN IRISH: A SYNCHRONIC AND DIACHRONIC ANALYSIS by Janine F. -

The Value of Irish Schwa: an Acoustic Analysis of Epenthetic Vowels

The value of Irish schwa: An acoustic analysis of epenthetic vowels Kerry McCullough∗ Department of Linguistics University of Kansas; Lawrence, KS, USA This study was conducted in an effort to learn more about the phonology of the Irish language. The research is intended to be a phonetic analysis of one of the phonological processes characteristic to Celtic languages. The present study examines the extent to which schwa epenthesis in Irish acts as a neutral- ization process. A list of 30 Irish words acting as near-minimal pairs was compiled for this study. Vowel environment and syllable count matched across pairs, and only the vowel itself differed in whether it was epenthetic or underlying. Six native-Irish speakers were recruited for this experiment representing all three major dialects of the language: three speakers from Cork (Munster), two speakers from Donegal (Ulster), one speaker from Connemara (Connacht). Participants read from the word list, reading each word twice. Acoustic analysis focused on two measurements: vowel duration and formant frequencies. The formants for each vowel type are comparable, but the difference in duration is significant, indicating that Irish schwa epenthesis is an incomplete neutralization process. While schwa epenthesis has been reported to create an identical phonological form to that of the underlying schwa, the significant difference in vowel duration indicates a residual contrast of the original underlying forms. Keywords: epenthesis, neutralization, Irish, vowel duration 1. Introduction Epenthesis is a recognized neutralization process found in a variety of world languages including Arabic, Welsh, Mono, and Dutch (Hall, 2006, 2011). The insertion of an underlyingly absent vowel neutralizes pre-existing contrasts between different lexical items. -

Can Language Be Planned? Can Language Be Planned? Contributors Contributors

Can Language Be Planned? Can Language Be Planned? Contributors Contributors S. TAKDIR ALISJAHBANA JYOTIRINDRA DAS GUPTA JOSHUA A. FISHMAN CHARLES F. GALLAGHER MUHAMMAD ABDUL HAI EINAR HAUGEN BJÖRN H. JERNUDD HERBERT KELMAN JOHN MACNAMARA CHAIM RABIN JOAN RUBIN BONIFACIO P. SIBAYAN THOMAS THORBURN WILFRED H. WHITELEY ii Can Language Be Planned? Sociolinguistic Theory and Practice for Developing Nations EDITED BY JOAN RUBIN AND BJÖRN H. JERNUDD An East-West Center Book The University Press of Hawaii Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824880705 (PDF) 9780824880712 (EPUB) This version created: 16 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. Copyright © 1971 by The University Press of Hawaii All rights reserved CONTENTS CONTENTS Preface viii Introduction: Language Planning as an Element in Modernization Joan Rubin and Björn H. Jernudd xi THE MOTIVATION AND RATIONALIZATION FOR LANGUAGE POLICY 1 1. The Impact of Nationalism on Language Planning: Some Comparisons between Early Twentieth-Century Europe and More Recent Years in South and Southeast Asia Joshua A. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Foot-conditioned phonotactics and prosodic constituency Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0hj9f173 Author Bennett, Ryan Thomas Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ FOOT-CONDITIONED PHONOTACTICS AND PROSODIC CONSTITUENCY A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Ryan T. Bennett September 2012 The Dissertation of Ryan T. Bennett is approved: Professor Junko Itô, Chair Professor Jaye Padgett, Chair Professor Armin Mester Assistant Professor Grant McGuire Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Ryan T. Bennett 2012 Table of Contents List of Figures vi List of Tables vii Abstract ix Dedication xi Acknowledgments xii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background .................................. 8 1.1.1 Thecrucibleoffoot-conditionedphonotactics . .. 9 1.2 Empiricalcontributions. 13 1.3 Theoreticaloverview:thebasics . 14 1.3.1 Themetricalfoot ........................... 14 1.3.2 Non-accentualevidenceforfooting . 20 1.4 Twometricalframeworks........... ........... ..... 26 1.4.1 Prosodichierarchytheory . 26 1.4.2 Simplifiedbracketedgridtheory . 35 2 Rhythmicity, prominence, and the uniqueness of footing 44 2.1 Huariapano................................... 44 2.2 PhonologyofHuariapano. 45 2.2.1 Segmentalinventory ......... ........... ..... 45 2.2.2 Syllablestructure ........................... 46 2.2.3 Stressplacement ........................... 47 2.2.4 Coda [h] epenthesis.......................... 50 2.3 DisjointfootinginHuariapano? . .. 54 2.3.1 Stressplacement ........................... 55 2.3.2 Coda [h] epenthesis.......................... 56 2.4 TowardsaunifiedaccountofHuariapano . 59 2.4.1 Stressplacement ........................... 61 iii 2.4.2 Coda [h] epenthesis.......................... 67 2.4.3 Are epenthetic [h]smoraic? .................... -

English Influence on L2 Speakers' Production of Palatalization And

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 English Influence on L2 Speakers’ Production of Palatalization and Velarization Jennifer C. Gabriele The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2592 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ENGLISH INFLUENCE ON L2 IRISH SPEAKERS’ PRODUCTION OF PALATALIZATION AND VELARIZATION by JENNIFER GABRIELE A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 JENNIFER GABRIELE All Rights Reserved ii English Influence on Second Language Irish Speakers’ Production of Palatalization and Velarization by Jennifer Gabriele This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date [Juliette Blevins] Thesis Advisor Date [Gita Martohardjono] Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT English Influence on L2 Speakers’ Production of Palatalization and Velarization by Jennifer Gabriele Advisor: Juliette Blevins Irish is a Celtic language spoken in Ireland. It is currently endangered with only 73,803 people using the language on a daily basis as of 2016 (Official Office of Statistics, 2016). The reason for the decline is that English is the dominate language, pushing Irish to the periphery. -

Prof. Raymond Hickey

Prof. Raymond Hickey Date: 23 Februar 2021 General Linguistics and Varieties of English Department of Anglophone Studies University of Duisburg and Essen 45141 Essen Germany email: [email protected] website: www.uni-due.de/~lan300/HICKEY.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Hickey Orcid.: 0000-0003-2354-0205 Education and academic career 2020 Adjunct Professor, University of Limerick, Irland 2020 Senior professor at the University of Duisburg-Essen. 1993 Chair for English linguistics, University of Essen. 1993 Offer of chair at the University of Bayreuth. 1991 Full professor, University of Munich. 1987 Associate professor, Bonn University. 1985 ‘Habilitation’ (post-doctoral degree), University of Bonn. 1980 PhD in general linguistics, University of Kiel. 1979 Lectureship in linguistics, English Department, University of Bonn. 1976 Foreign language assistant, English Department, University of Kiel. 1971-1975 Study at Trinity College, Dublin (M.A. in German and Italian) 1965-1971 Secondary School, De La Salle, Waterford. 1964-1965 Irish-speaking boarding school, Coláiste na Rinne, Co Waterford. 1958-1964 Primary School, Waterpark College, Waterford. 3.6.1954 Born in Dublin, Republic of Ireland. Professional activities and appointments 2020 Visiting Professor, University of Florence, Italy 2015 Visiting Professor, University of Cape Town, South Africa 2009/10 Visiting Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland 2007 Visiting Professor, University of Bergamo, Italy 2001/2 Visiting Professor, University of Innbruck, Austria 1997 Visiting Professor, University of Uppsala, Sweden Numerous guest lectures at universities in Canada, USA, Australia, South Africa, United Kingdom, Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Spain, Italy, France, The Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, Russian Federation, China. Raymond Hickey Curriculum vitae Page 2 of 28 External examiner at various universities, e.g. -

On Feature Spreading and the Representation of Place of Articulation Morris Halle Bert Vaux Andrew Wolfe

On Feature Spreading and the Representation of Place of Articulation Morris Halle Bert Vaux Andrew Wolfe Since Clements (1985) introduced feature geometry, four major inno- vations have been proposed: Unified Feature Theory, Vowel-Place Theory, Strict Locality, and Partial Spreading. We set out the problems that each innovation encounters and propose a new model of feature geometry and feature spreading that is not subject to these problems. Of the four innovations, the new model—Revised Articulator Theory (RAT)—keeps Partial Spreading, but rejects the rest. RAT also intro- duces a new type of unary feature—one for each articulator—to indi- cate that the articulator is the designated articulator of the segment. Keywords: phonology, phonetics, feature geometry, Unified Feature Theory, Vowel-Place Theory 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Since the introduction of feature geometry (Clements 1985, McCarthy 1988), four major innova- tions in the theory have been proposed: 1. Unified Feature Theory, which employs a single set of Place features for both consonants and vowels (Clements 1989); 2. Vowel-Place Theory, which maintains that vocalic and consonantal Place features are segregated (Clements 1989, 1991, 1993, N´õ Chiosa´in and Padgett 1993, Clements and Hume 1995); 3. Partial Spreading, which allows spreading of two or more features that are not exhaus- tively dominated by a common node (Sagey 1987, Halle 1995, Padgett 1995); 4. Strict Locality, which prohibits spreading from skipping segments (N´õ Chiosa´in and Pad- gett 1993, 1997, Gafos 1998, Flemming 1995). Many thanks to Ben Bruening, Andrea Calabrese, Nick Clements, FranCois Dell, Ma´ire N´õ Chiosa´in, Michael Kens- towicz, Jaye Padgett, and Cheryl Zoll for helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, which was initially circulated in 1993. -

Predicting Dual-Language Literacy Attainment in Irish-English Bilinguals: Language-Specific and Language-Universal Contributions

Predicting dual-language literacy attainment in Irish-English bilinguals: language-specific and language-universal contributions Emily Barnes Supervisors: Professors Ailbhe Ní Chasaide and Neasa Ní Chiaráin Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Phonetics and Speech Laboratory School of Linguistic, Communication and Speech Sciences Trinity College Dublin January 2021 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the Library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. I consent to the examiner retaining a copy of the thesis beyond the examining period, should they so wish. Signature of author: Emily Barnes i Acknowledgements This research would not have been possible without the support and commitment of many people, to whom I am very grateful. Ba mhaith liom buíochas ó chroí a ghabháil leis na hOllaimh Ailbhe Ní Chasaide agus Neasa Ní Chiaráin as an léargas, tacaíocht, misneach agus cairdeas a thug sibh dom thar na blianta. Tá mé tar éis i bhfad níos mó ná an méid atá sa tráchtas seo a fhoghlaim uaibhse. Ba mhaith liom buíochas mór a ghabháil leis an Dr. John Harris, leis an Dr. Claire Dunne agus leis an Ollamh Ram Frost as an léargas agus an saineolas a roinn sibh liom - thug sibh súil eile dom. Ba mhaith liom buíochas a ghabháil le daoine eile i réimse an oideachais agus i réimse na litearthachta a thug comhairle agus deiseanna foghlama dom le linn na céime, go háirithe leis an Ollamh Noel Ó Murchadha. -

Areal Features of English in Ireland

Areal features of English in Ireland Raymond Hickey University of Duisburg and Essen 1. Introduction The notion of linguistic area (from German Sprachbund, lit. ‘language federation’) is one which is often invoked when dealing with languages which share features and are found in a geographically contiguous area. Some of these areas have gained general acceptance in linguistic literature as the evidence for them is quite convincing. These include the Pacific North-West, Meso-America, the Balkans, the Baltic area, Arnhem Land in Northern Australia, Southern India (with Indic / Dravidian languages) to mention just some of the better known instances. Scholars concerned with linguistic areas, vary considerably in their approach and following Campbell (1998: 300) one can distinguish at least two basic orientations in the field: 1) circumstantianlist where authors are content with listing the various features of a putative area and 2) historicist where authors attempt to show that the shared features diffused historically through the languages of an area. The second approach is necessary to avoid the pitfall of raising features which may have arisen by chance to the level of defining characteristics of an area. Furthermore, it is essential to accord relative weight to features under consideration. Those which are typologically unspectacular cannot be appealed to when defining an area. For instance any set of languages or varieties which show a palatalisation of velars – and just that – could hardly be regarded as forming a linguistic area as this is a very general feature. On the other hand languages in an enclosed area which develop phonemic tone would be good candidates for a linguistic area. -

Quantity in Phonetics and Phonology: a Government Perspective

ROCZNIKI HUMANISTYCZNE Tom LXII, zeszyt 5 – 2014 ANNA BLOCH-ROZMEJ * QUANTITY IN PHONETICS AND PHONOLOGY: A GOVERNMENT PERSPECTIVE A b s t r a c t. The major aim of this article is to discuss the phonetic manifestation of phono- logical structure as regards the dimension of quantity. The model adopted in the analysis is that of Government Phonology which remains in sharp contrast with the generative framework that employed distinctive features and binary feature values to express the phonological opposition between short and long phonemic units. Government Phonology represents quantity on a separate autonomous level consisting of skeletal positions. We shall pinpoint the major problems pertaining to the phonetics—phonology interface as re- gards the dimension of quantity. To this end, the linguistic systems of English, Irish or Japanese will provide us with examples depicting the existing mismatches between the phonological represen- tations of quantity and their phonetic manifestations. Interestingly, what sounds short or long phone- tically not always need to be the manifestation of the two corresponding structural configurations. Key words: quantity, quality, structure, stability, manifestation, interface. 1. INTRODUCTION The phonetic manifestation of phonologically-encoded information has always occupied a significant place in phonological investigations. Analyses couched within the generative framework employed distinctive features and binary feature values to express the phonological opposition between short and long phonemic units. Government Phonology (henceforth GP) departs from such an approach to quantity. The model proposed by Kaye, Lowen- stamm and Vergnaud (1985, 1990) (henceforth KLV) and developed in Cha- rette (1991), Harris (1994), or Cyran (2003, 2010), Scheer (2004), Bloch- Rozmej (2008), represents quantity on a separate autonomous level con- Dr. -

The Impact of Input on Acquisition of Irish As a First Language

Investigating the later stages of Irish acquisition Iniúchadh ar shealbhú níos déanaí na Gaeilge Siobhán Nic Fhlannchadha 08633631 This thesis is submitted to University College Dublin in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Psychology College of Social Sciences and Law Head of School: Dr. Suzanne Guerin Principal Supervisor: Dr. Tina Hickey Chair of Doctoral Studies Panel: Dr. Eilis Hennessy Member of Doctoral Studies Panel: Prof. Aidan Moran February 2016 Table of Contents Abstract Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................. ii Abstract .......................................................................................................................................................... vi List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... vii List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. viii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................. xi Statement of Original Authorship ................................................................................................................. xiii Acknowledgements .....................................................................................................................................