Areal Features of English in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British, Scottish, English?

Scottish, English, British? coding for attitude in the UK Carmen Llamas University of York, UK Satellite Workshop for Sociolinguistic Archival Preparation attitudes ‘attitudes to language varieties underpin all manners of sociolinguistic and social psychological phenomena’ (Garrett et al., 2003: 12) ‘a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor’ (Eagley & Chaiken, 1993: 1) . components: cognitive beliefs affective feelings behavioural readiness for action speaker-internal mental constructs - methodologically challenging • direct and indirect observation: •explicit attitudes – e.g. interviews, self-completion written questionnaires • implicit attitudes – e.g. matched-guise technique, IATs borders • ideal test site for investigation of how variable linguistic behaviour is connected to attitudes – border area • fluid and complex identity construction at such sites mean border regions have particular sociolinguistic relevance • previous sociological research in and around Berwick-upon- Tweed (English town) (Kiely et al. 2000) – around half informants felt Scottish some of the time the border • Scottish~English border still seen as particularly divisive: What appears to be the most numerous bundle of dialect isoglosses in the English-speaking world runs along this border, effectively turning Scotland into a “dialect island”. (Aitken 1992:895) • predicted to become more divisive still: the Border is becoming more and more distinct linguistically as the 20th century progresses. (Kay 1986:22) ... the dividing effect of the geographical border is bound to increase. (Glauser 2000: 70) • AISEB tests these predictions by examining the linguistic and socio-psychological effects of the border the team Dominic Watt (York) Gerry Docherty (Newcastle) Damien Hall (Kent) Jennifer Nycz (Reed College) UK Economic & Social Research Council (RES-062-23-0525) AISEB three-pronged approach production • quantitative analysis of phonological variation and change attitude • cognitive vs. -

The Past, Present, and Future of English Dialects: Quantifying Convergence, Divergence, and Dynamic Equilibrium

Language Variation and Change, 22 (2010), 69–104. © Cambridge University Press, 2010 0954-3945/10 $16.00 doi:10.1017/S0954394510000013 The past, present, and future of English dialects: Quantifying convergence, divergence, and dynamic equilibrium WARREN M AGUIRE AND A PRIL M C M AHON University of Edinburgh P AUL H EGGARTY University of Cambridge D AN D EDIU Max-Planck-Institute for Psycholinguistics ABSTRACT This article reports on research which seeks to compare and measure the similarities between phonetic transcriptions in the analysis of relationships between varieties of English. It addresses the question of whether these varieties have been converging, diverging, or maintaining equilibrium as a result of endogenous and exogenous phonetic and phonological changes. We argue that it is only possible to identify such patterns of change by the simultaneous comparison of a wide range of varieties of a language across a data set that has not been specifically selected to highlight those changes that are believed to be important. Our analysis suggests that although there has been an obvious reduction in regional variation with the loss of traditional dialects of English and Scots, there has not been any significant convergence (or divergence) of regional accents of English in recent decades, despite the rapid spread of a number of features such as TH-fronting. THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF ENGLISH DIALECTS Trudgill (1990) made a distinction between Traditional and Mainstream dialects of English. Of the Traditional dialects, he stated (p. 5) that: They are most easily found, as far as England is concerned, in the more remote and peripheral rural areas of the country, although some urban areas of northern and western England still have many Traditional Dialect speakers. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

Understanding Irish Spelling

Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey Understanding Irish Spelling A Handbook for Teachers and Learners Nancy Stenson and Tina Hickey i © Stenson and Hickey 2018 ii Acknowledgements The preparation of this publication was supported by a grant from An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta, and we wish to express our sincere thanks to COGG, and to Muireann Ní Mhóráin and Pól Ó Cainín in particular. We acknowledge most gratefully the support of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship scheme for enabling this collaboration through its funding of an Incoming International Fellowship to the first author, and to UCD School of Psychology for hosting her as an incoming fellow and later an as Adjunct Professor. We also thank the Fulbright Foundation for the Fellowship they awarded to Prof. Stenson prior to the Marie Curie fellowship. Most of all, we thank the educators at first, second and third level who shared their experience and expertise with us in the research from which we draw in this publication. We benefitted significantly from input from many sources, not all of whom can be named here. Firstly, we wish to thank most sincerely all of the participants in our qualitative study interviews, who generously shared their time and expertise with us, and those in the schools that welcomed us to their classrooms and facilitated observation and interviews. We also wish to thank the participants at many conferences, seminars and presentations, particularly those in Bangor, Berlin, Brighton, Hamilton and Ottawa, as well as those in several educational institutions in Ireland who offered comments and suggestions. -

L Vocalisation As a Natural Phenomenon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Essex Research Repository L Vocalisation as a Natural Phenomenon Wyn Johnson and David Britain Essex University [email protected] [email protected] 1. Introduction The sound /l/ is generally characterised in the literature as a coronal lateral approximant. This standard description holds that the sounds involves contact between the tip of the tongue and the alveolar ridge, but instead of the air being blocked at the sides of the tongue, it is also allowed to pass down the sides. In many (but not all) dialects of English /l/ has two allophones – clear /l/ ([l]), roughly as described, and dark, or velarised, /l/ ([…]) involving a secondary articulation – the retraction of the back of the tongue towards the velum. In dialects which exhibit this allophony, the clear /l/ occurs in syllable onsets and the dark /l/ in syllable rhymes (leaf [li˘f] vs. feel [fi˘…] and table [te˘b…]). The focus of this paper is the phenomenon of l-vocalisation, that is to say the vocalisation of dark /l/ in syllable rhymes 1. feel [fi˘w] table [te˘bu] but leaf [li˘f] 1 This process is widespread in the varieties of English spoken in the South-Eastern part of Britain (Bower 1973; Hardcastle & Barry 1989; Hudson and Holloway 1977; Meuter 2002, Przedlacka 2001; Spero 1996; Tollfree 1999, Trudgill 1986; Wells 1982) (indeed, it appears to be categorical in some varieties there) and which extends to many other dialects including American English (Ash 1982; Hubbell 1950; Pederson 2001); Australian English (Borowsky 2001, Borowsky and Horvath 1997, Horvath and Horvath 1997, 2001, 2002), New Zealand English (Bauer 1986, 1994; Horvath and Horvath 2001, 2002) and Falkland Island English (Sudbury 2001). -

Chapter 1. Introduction

1 Chapter 1. Introduction Once an English-speaking population was established in South Africa in the 19 th century, new unique dialects of English began to emerge in the colony, particularly in the Eastern Cape, as a result of dialect levelling and contact with indigenous groups and the L1 Dutch speaking population already present in the country (Lanham 1996). Recognition of South African English as a variety in its own right came only later in the next century. South African English, however, is not a homogenous dialect; there are many different strata present under this designation, which have been recognised and identified in terms of geographic location and social factors such as first language, ethnicity, social class and gender (Hooper 1944a; Lanham 1964, 1966, 1967b, 1978b, 1982, 1990, 1996; Bughwan 1970; Lanham & MacDonald 1979; Barnes 1986; Lass 1987b, 1995; Wood 1987; McCormick 1989; Chick 1991; Mesthrie 1992, 1993a; Branford 1994; Douglas 1994; Buthelezi 1995; Dagut 1995; Van Rooy 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; Gough 1996; Malan 1996; Smit 1996a, 1996b; Görlach 1998c; Van der Walt 2000; Van Rooy & Van Huyssteen 2000; de Klerk & Gough 2002; Van der Walt & Van Rooy 2002; Wissing 2002). English has taken different social roles throughout South Africa’s turbulent history and has presented many faces – as a language of oppression, a language of opportunity, a language of separation or exclusivity, and also as a language of unification. From any chosen theoretical perspective, the presence of English has always been a point of contention in South Africa, a combination of both threat and promise (Mawasha 1984; Alexander 1990, 2000; de Kadt 1993, 1993b; de Klerk & Bosch 1993, 1994; Mesthrie & McCormick 1993; Schmied 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; de Klerk 1996b, 2000; Granville et al. -

Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View

37 Manx Place-Names: an Ulster View Kay Muhr In this chapter I will discuss place-name connections between Ulster and Man, beginning with the early appearances of Man in Irish tradition and its association with the mythological realm of Emain Ablach, from the 6th to the I 3th century. 1 A good introduction to the link between Ulster and Manx place-names is to look at Speed's map of Man published in 1605.2 Although the map is much later than the beginning of place-names in the Isle of Man, it does reflect those place-names already well-established 400 years before our time. Moreover the gloriously exaggerated Manx-centric view, showing the island almost filling the Irish sea between Ireland, Scotland, England and Wales, also allows the map to illustrate place-names from the coasts of these lands around. As an island visible from these coasts Man has been influenced by all of them. In Ireland there are Gaelic, Norse and English names - the latter now the dominant language in new place-names, though it was not so in the past. The Gaelic names include the port towns of Knok (now Carrick-) fergus, "Fergus' hill" or "rock", the rock clearly referring to the site of the medieval castle. In 13th-century Scotland Fergus was understood as the king whose migration introduced the Gaelic language. Further south, Dundalk "fort of the small sword" includes the element dun "hill-fort", one of three fortification names common in early Irish place-names, the others being rath "ring fort" and lios "enclosure". -

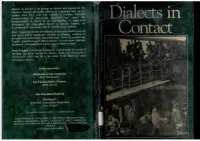

Dialects in Contact Language, Resulting for New Towns and at Transplanted Varieties of Research Into Example from Urbanization and Colonization

1 observe and account for (he Directs in Contact is an aliempt to a language have on one influence mutually intelligible dialects Of examines UngttistM another when they come into contact, h and argues th.it accommodation in faee-to-face interaction Dialects in of longer-term accommodation is crucial to an understanding features, the phenomena: the geographical spread of linguistic development of 'interdialect* and the growth of new dialects. border areas and Peter Trudgill looks at the development of dialects in Contact language, resulting for new towns and at transplanted varieties of research into example from urbanization and colonization. Based on draws important English. Scandinavian and other languages, his book linguistic data. I'll f theoretical conclusions from a wide range of Science at the Universitj of Peter Trudgill is Professor in Linguistic I Geographical Reading. His books include On Dialect: Social and Blackwell series Perspectives (1983) and he is the editor of the Language in Society. In the same series Pidgin and Creole Linguistics Peter Mtihlhausler The Sociolinguistics of Society Ralph Fasold Also from Basil Blackwell On Dialect* Social and Geographical Perspectives Peter Trudgill m is not available in the USA I, ir copyright reasons this edition Alfred Stieglitz. photogravure (artist's Cover illustration: 77k- Steerage, 1907. by collection. The proof) from Camera Work no. 36. 1911. size of print. 7)4 reproduced by k.nd Museum of Modern An. New York, gilt of Alfred Stieglitz. is permission Cover design by Martin Miller LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY Dialects in Contact GENERAL EDITOR: Peter Trudgill, Professor of Linguistic Science, University of Reading PETER TRUDGILL advisory editors: Ralph Fasold, Professor of Linguistics, Georgetown University William Labov, Professor of Linguistics, University of Pennsylvania 1 Language and Social Psychology Edited by Howard Giles and Robert N. -

Download the Programme for the Xvith International Congress of Celtic Studies

Logo a chynllun y clawr Cynlluniwyd logo’r XVIeg Gyngres gan Tom Pollock, ac mae’n seiliedig ar Frigwrn Capel Garmon (tua 50CC-OC50) a ddarganfuwyd ym 1852 ger fferm Carreg Goedog, Capel Garmon, ger Llanrwst, Conwy. Ceir rhagor o wybodaeth ar wefan Sain Ffagan Amgueddfa Werin Cymru: https://amgueddfa.cymru/oes_haearn_athrawon/gwrthrychau/brigwrn_capel_garmon/?_ga=2.228244894.201309 1070.1562827471-35887991.1562827471 Cynlluniwyd y clawr gan Meilyr Lynch ar sail delweddau o Lawysgrif Bangor 1 (Archifau a Chasgliadau Arbennig Prifysgol Bangor) a luniwyd yn y cyfnod 1425−75. Mae’r testun yn nelwedd y clawr blaen yn cynnwys rhan agoriadol Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, cyfieithiad Cymraeg o De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum, gan Hu Sant (Hugo o St. Victor). Rhan o ramadeg barddol a geir ar y clawr ôl. Logo and cover design The XVIth Congress logo was designed by Tom Pollock and is based on the Capel Garmon Firedog (c. 50BC-AD50) which was discovered in 1852 near Carreg Goedog farm, Capel Garmon, near Llanrwst, Conwy. Further information will be found on the St Fagans National Museum of History wesite: https://museum.wales/iron_age_teachers/artefacts/capel_garmon_firedog/?_ga=2.228244894.2013091070.156282 7471-35887991.1562827471 The cover design, by Meilyr Lynch, is based on images from Bangor 1 Manuscript (Bangor University Archives and Special Collections) which was copied 1425−75. The text on the front cover is the opening part of Pwyll y Pader o Ddull Hu Sant, a Welsh translation of De Quinque Septenis seu Septenariis Opusculum (Hugo of St. Victor). The back-cover text comes from the Bangor 1 bardic grammar. -

Newfoundland English

Izaro Zalacain Mendia Degree in English Studies 2019-2020 NEWFOUNDLAND ENGLISH Supervisor: Miren Alazne Landa Departamento de Filología Inglesa, Alemana y de Traducción e Interpretación Área de Filología Inglesa Abstract The English language has undergone many variations, leaving uncountable dialects in every nook and cranny of the world. Located at the north-east of Canada, the island of Newfoundland presents one of those dialects. However, within the many varieties the English language features, Newfoundland English (NE) remains as one of the less researched dialects in North America. The aim of this paper is to provide a characterisation of NE. In order to do so, this paper focuses on research questions on the origins of the dialect, potential variation within NE, the languages it has been in contact with, its particular linguistic features and the role of linguistic distinction in the Newfoundlander identity. Thus, in this paper I firstly assess the origins of NE, which are documented to mainly derive from West Country, England, and south-eastern Ireland, and I also provide an overview of the main historical events that have influenced the language. Secondly, I show the linguistic variation NE features, thus displaying the multiple dialectal areas that are found in the island. Furthermore, I discuss the different languages that have been in contact with the variety, namely, Irish Gaelic and Micmac, among others. Thirdly, I present a variety of linguistic features of NE -both phonetic and morphosyntactic- that distinguish the dialect from the rest of North American varieties, including Canadian English. Finally, I tackle the issue of language and identity and uncover a number of innovations and purposeful uses of certain features that the islanders show in their speech for the sake of identity marking. -

Index of Linguistic Items

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42359-5 — The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language 3rd Edition David Crystal Index More Information VI INDEX OF LINGUISTIC ITEMS A auto 322, 330, 493 classist 189 -eau(x) 213 auto- 138 c’mon 79 -ectomy 210 a indefinite article 234–5, 350 aye 346 co- 138 -ed form 208, 210, 216, 223, 224, 237, short vs long 327, 345, 371 cockroach 149 346, 350 verb particle 367 B colour 179 -ed vs t (verb ending) 216, 331, 493 a- 138, 335 contra- 138 -ee 210, 220 -a noun singular 212 /b-/, /-b/ (sound symbolism) 263 could 224 -een 358 noun plural 212 B/b 271, 280 counter- 138 -eer 210, 220 -a- (linking vowel) 139 babbling 483 cowboy 148 eh 319 A/a 271, 280 back of 331 crime 176 eh? 230, 362 AA (abbreviations) 131 bad 211 curate’s egg 437 elder/eldest 211 -able 210, 223 barely 230 cyber- 452 elfstedentocht 383 ableism 189 bastard 263 Elizabeth 158 -acea 210 be 224, 233, 237, 243, 367 D -elle 160 a crapella 498 inflected 21, 363 ’em 287 -ae (plural) 213 regional variation 342 /d-/, /-d/ (sound symbolism) 263 en- 138 after (aspectual) 358, 363 be- 138 D/d 271, 280–1 encyclop(a)edia 497 -age 210, 220 be about to 236 da 367 encyclopediathon 143 ageist 189 been 367 danfo 495 -ene 160 agri- 139 be going to 96, 236 dare 224 -en form 21, 210, 212, -aholic 139 Berks 97 data 213 346, 461 -aid 143, 191 best 211 daviely 352 Englexit 124 ain’t 319, 498 be to 236 De- 160 -er adjective base ending 211 aitch 359 better 211 de- 138 familiarity marker 141, 210 -al 210, 220, 223 between you and I 206, 215 demi- 138 noun ending