New Zealand English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

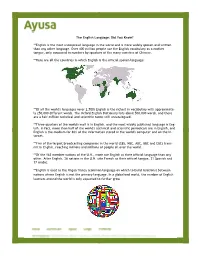

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Portrayals of the Moriori People

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i Portrayals of the Moriori People Historical, Ethnographical, Anthropological and Popular sources, c. 1791- 1989 By Read Wheeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Massey University, 2016 ii Abstract Michael King’s 1989 book, Moriori: A People Rediscovered, still stands as the definitive work on the Moriori, the Native people of the Chatham Islands. King wrote, ‘Nobody in New Zealand – and few elsewhere in the world- has been subjected to group slander as intense and as damaging as that heaped upon the Moriori.’ Since its publication, historians have denigrated earlier works dealing with the Moriori, arguing that the way in which they portrayed Moriori was almost entirely unfavourable. This thesis tests this conclusion. It explores the perspectives of European visitors to the Chatham Islands from 1791 to 1989, when King published Moriori. It does this through an examination of newspapers, Native Land Court minutes, and the writings of missionaries, settlers, and ethnographers. The thesis asks whether or not historians have been selective in their approach to the sources, or if, perhaps, they have ignored the intricacies that may have informed the views of early observers. The thesis argues that during the nineteenth century both Maori and European perspectives influenced the way in which Moriori were portrayed in European narrative. -

British, Scottish, English?

Scottish, English, British? coding for attitude in the UK Carmen Llamas University of York, UK Satellite Workshop for Sociolinguistic Archival Preparation attitudes ‘attitudes to language varieties underpin all manners of sociolinguistic and social psychological phenomena’ (Garrett et al., 2003: 12) ‘a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor’ (Eagley & Chaiken, 1993: 1) . components: cognitive beliefs affective feelings behavioural readiness for action speaker-internal mental constructs - methodologically challenging • direct and indirect observation: •explicit attitudes – e.g. interviews, self-completion written questionnaires • implicit attitudes – e.g. matched-guise technique, IATs borders • ideal test site for investigation of how variable linguistic behaviour is connected to attitudes – border area • fluid and complex identity construction at such sites mean border regions have particular sociolinguistic relevance • previous sociological research in and around Berwick-upon- Tweed (English town) (Kiely et al. 2000) – around half informants felt Scottish some of the time the border • Scottish~English border still seen as particularly divisive: What appears to be the most numerous bundle of dialect isoglosses in the English-speaking world runs along this border, effectively turning Scotland into a “dialect island”. (Aitken 1992:895) • predicted to become more divisive still: the Border is becoming more and more distinct linguistically as the 20th century progresses. (Kay 1986:22) ... the dividing effect of the geographical border is bound to increase. (Glauser 2000: 70) • AISEB tests these predictions by examining the linguistic and socio-psychological effects of the border the team Dominic Watt (York) Gerry Docherty (Newcastle) Damien Hall (Kent) Jennifer Nycz (Reed College) UK Economic & Social Research Council (RES-062-23-0525) AISEB three-pronged approach production • quantitative analysis of phonological variation and change attitude • cognitive vs. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Standard Southern British English As Referee Design in Irish Radio Advertising

Joan O’Sullivan Standard Southern British English as referee design in Irish radio advertising Abstract: The exploitation of external as opposed to local language varieties in advertising can be associated with a history of colonization, the external variety being viewed as superior to the local (Bell 1991: 145). Although “Standard English” in terms of accent was never an exonormative model for speakers in Ireland (Hickey 2012), nevertheless Ireland’s history of colonization by Britain, together with the geographical proximity and close socio-political and sociocultural connections of the two countries makes the Irish context an interesting one in which to examine this phenomenon. This study looks at how and to what extent standard British Received Pronunciation (RP), now termed Standard Southern British English (SSBE) (see Hughes et al. 2012) as opposed to Irish English varieties is exploited in radio advertising in Ireland. The study is based on a quantitative and qualitative analysis of a corpus of ads broadcast on an Irish radio station in the years 1977, 1987, 1997 and 2007. The use of SSBE in the ads is examined in terms of referee design (Bell 1984) which has been found to be a useful concept in explaining variety choice in the advertising context and in “taking the ideological temperature” of society (Vestergaard and Schroder 1985: 121). The analysis is based on Sussex’s (1989) advertisement components of Action and Comment, which relate to the genre of the discourse. Keywords: advertising, language variety, referee design, language ideology. 1 Introduction The use of language variety in the domain of advertising has received considerable attention during the past two decades (for example, Bell 1991; Lee 1992; Koslow et al. -

Not Taking Yourself Too Seriously in Australian English: Semantic Explications, Cultural Scripts, Corpus Evidence

Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence Author Goddard, Cliff Published 2009 Journal Title Intercultural Pragmatics Version Version of Record (VoR) DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/IPRG.2009.002 Copyright Statement © 2009 Walter de Gruyter & Co. KG Publishers. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/44428 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence CLIFF GODDARD Abstract In the mainstream speech culture of Australia (as in the UK, though per- haps more so in Australia), taking yourself too seriously is culturally proscribed. This study applies the techniques of Natural Semantic Meta- language (NSM) semantics and ethnopragmatics (Goddard 2006b, 2008; Wierzbicka 1996, 2003, 2006a) to this aspect of Australian English speech culture. It first develops a semantic explication for the language-specific ex- pression taking yourself too seriously, thus helping to give access to an ‘‘in- sider perspective’’ on the practice. Next, it seeks to identify some of the broader communicative norms and social attitudes that are involved, using the method of cultural scripts (Goddard and Wierzbicka 2004). Finally, it investigates the extent to which predictions generated from the analysis can be supported or disconfirmed by contrastive analysis of Australian English corpora as against other English corpora, and by the use of the Google search engine to explore di¤erent subdomains of the World Wide Web. -

The Ideology of American English As Standard English in Taiwan

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume.7 Number.4 December, 2016 Pp. 80 - 96 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Jackie Chang English Department, National Pingtung University Pingtung City, Taiwan Abstract English language teaching and learning in Taiwan usually refers to American English teaching and learning. Taiwan views American English as Standard English. This is a strictly perceptual and ideological issue, as attested in the language school promotional materials that comprise the research data. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was employed to analyze data drawn from language school promotional materials. The results indicate that American English as Standard English (AESE) ideology is prevalent in Taiwan. American English is viewed as correct, superior and the proper English language version for Taiwanese people to compete globally. As a result, Taiwanese English language learners regard native English speakers with an American accent as having the greatest prestige and as model teachers deserving emulation. This ideology has resulted in racial and linguistic inequalities in contemporary Taiwanese society. AESE gives Taiwanese learners a restricted knowledge of English and its underlying culture. It is apparent that many Taiwanese people need tore-examine their taken-for-granted beliefs about AESE. Keywords: American English as Standard English (AESE),Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), ideology, inequalities 80 Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Vol.7. No. 4 December 2016 The Ideology of American English as Standard English in Taiwan Chang Introduction It is an undeniable fact that English has become the global lingua franca. However, as far as English teaching and learning are concerned, there is a prevailing belief that the world should be learning not just any English variety but rather what is termed Standard English. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

Immigration During the Crown Colony Period, 1840-1852

1 2: Immigration during the Crown Colony period, 1840-1852 Context In 1840 New Zealand became, formally, a part of the British Empire. The small and irregular inflow of British immigrants from the Australian Colonies – the ‘Old New Zealanders’ of the mission stations, whaling stations, timber depots, trader settlements, and small pastoral and agricultural outposts, mostly scattered along the coasts - abruptly gave way to the first of a number of waves of immigrants which flowed in from 1840.1 At least three streams arrived during the period 1840-1852, although ‘Old New Zealanders’ continued to arrive in small numbers during the 1840s. The first consisted of the government officials, merchants, pastoralists, and other independent arrivals, the second of the ‘colonists’ (or land purchasers) and the ‘emigrants’ (or assisted arrivals) of the New Zealand Company and its affiliates, and the third of the imperial soldiers (and some sailors) who began arriving in 1845. New Zealand’s European population grew rapidly, marked by the establishment of urban communities, the colonial capital of Auckland (1840), and the Company settlements of Wellington (1840), Petre (Wanganui, 1840), New Plymouth (1841), Nelson (1842), Otago (1848), and Canterbury (1850). Into Auckland flowed most of the independent and military streams, and into the company settlements those arriving directly from the United Kingdom. Thus A.S.Thomson observed that ‘The northern [Auckland] settlers were chiefly derived from Australia; those in the south from Great Britain. The former,’ he added, ‘were distinguished for colonial wisdom; the latter for education and good home connections …’2 Annexation occurred at a time when emigration from the United Kingdom was rising. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

Chapter 1. Introduction

1 Chapter 1. Introduction Once an English-speaking population was established in South Africa in the 19 th century, new unique dialects of English began to emerge in the colony, particularly in the Eastern Cape, as a result of dialect levelling and contact with indigenous groups and the L1 Dutch speaking population already present in the country (Lanham 1996). Recognition of South African English as a variety in its own right came only later in the next century. South African English, however, is not a homogenous dialect; there are many different strata present under this designation, which have been recognised and identified in terms of geographic location and social factors such as first language, ethnicity, social class and gender (Hooper 1944a; Lanham 1964, 1966, 1967b, 1978b, 1982, 1990, 1996; Bughwan 1970; Lanham & MacDonald 1979; Barnes 1986; Lass 1987b, 1995; Wood 1987; McCormick 1989; Chick 1991; Mesthrie 1992, 1993a; Branford 1994; Douglas 1994; Buthelezi 1995; Dagut 1995; Van Rooy 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; Gough 1996; Malan 1996; Smit 1996a, 1996b; Görlach 1998c; Van der Walt 2000; Van Rooy & Van Huyssteen 2000; de Klerk & Gough 2002; Van der Walt & Van Rooy 2002; Wissing 2002). English has taken different social roles throughout South Africa’s turbulent history and has presented many faces – as a language of oppression, a language of opportunity, a language of separation or exclusivity, and also as a language of unification. From any chosen theoretical perspective, the presence of English has always been a point of contention in South Africa, a combination of both threat and promise (Mawasha 1984; Alexander 1990, 2000; de Kadt 1993, 1993b; de Klerk & Bosch 1993, 1994; Mesthrie & McCormick 1993; Schmied 1995; Wade 1995, 1997; de Klerk 1996b, 2000; Granville et al.