Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

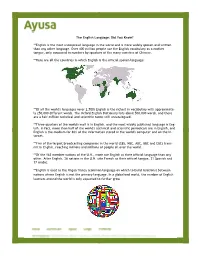

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

Not Taking Yourself Too Seriously in Australian English: Semantic Explications, Cultural Scripts, Corpus Evidence

Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence Author Goddard, Cliff Published 2009 Journal Title Intercultural Pragmatics Version Version of Record (VoR) DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/IPRG.2009.002 Copyright Statement © 2009 Walter de Gruyter & Co. KG Publishers. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/44428 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence CLIFF GODDARD Abstract In the mainstream speech culture of Australia (as in the UK, though per- haps more so in Australia), taking yourself too seriously is culturally proscribed. This study applies the techniques of Natural Semantic Meta- language (NSM) semantics and ethnopragmatics (Goddard 2006b, 2008; Wierzbicka 1996, 2003, 2006a) to this aspect of Australian English speech culture. It first develops a semantic explication for the language-specific ex- pression taking yourself too seriously, thus helping to give access to an ‘‘in- sider perspective’’ on the practice. Next, it seeks to identify some of the broader communicative norms and social attitudes that are involved, using the method of cultural scripts (Goddard and Wierzbicka 2004). Finally, it investigates the extent to which predictions generated from the analysis can be supported or disconfirmed by contrastive analysis of Australian English corpora as against other English corpora, and by the use of the Google search engine to explore di¤erent subdomains of the World Wide Web. -

A Longitudinal Study of Fear, Attitudes and Beliefs About Childbirth from a Cohort of Australian and Swedish Women

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 843 ‘No worries’ A longitudinal study of fear, attitudes and beliefs about childbirth from a cohort of Australian and Swedish women HELEN HAINES ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6206 ISBN 978-91-554-8547-4 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-185081 2012 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Auditorium Minus, Gustavianum, Akademigatan 3, Uppsala, Friday, January 18, 2013 at 02:10 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Faculty of Medicine). The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Haines, H. 2012. ‘No worries’: A longitudinal study of fear, attitudes and beliefs about childbirth from a cohort of Australian and Swedish women. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 843. 99 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-8547-4. Much is known about childbirth fear in Sweden including its relationship to caesarean birth. Less is understood about this in Australia. Sweden has half the rate of caesarean birth compared to Australia. Little has been reported about women’s beliefs and attitudes to birth in either country. The contribution of psychosocial factors such as fear, attitudes and beliefs about childbirth to the global escalation of caesarean birth in high-income countries is an important topic of debate. The overall aim of this thesis is to investigate the prevalence and impact of fear on birthing outcomes in two cohorts of pregnant women from Australia and Sweden and to explore the birth attitudes and beliefs of these women. A prospective longitudinal cohort study from two towns in Australia and Sweden (N=509) was undertaken in the years 2007-2009. -

LANGUAGE VARIETY in ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England

LANGUAGE VARIETY IN ENGLAND 1 ♦ Language Variety in England One thing that is important to very many English people is where they are from. For many of us, whatever happens to us in later life, and however much we move house or travel, the place where we grew up and spent our childhood and adolescence retains a special significance. Of course, this is not true of all of us. More often than in previous generations, families may move around the country, and there are increasing numbers of people who have had a nomadic childhood and are not really ‘from’ anywhere. But for a majority of English people, pride and interest in the area where they grew up is still a reality. The country is full of football supporters whose main concern is for the club of their childhood, even though they may now live hundreds of miles away. Local newspapers criss-cross the country in their thousands on their way to ‘exiles’ who have left their local areas. And at Christmas time the roads and railways are full of people returning to their native heath for the holiday period. Where we are from is thus an important part of our personal identity, and for many of us an important component of this local identity is the way we speak – our accent and dialect. Nearly all of us have regional features in the way we speak English, and are happy that this should be so, although of course there are upper-class people who have regionless accents, as well as people who for some reason wish to conceal their regional origins. -

In Britain, Standard English Is a Central Issue of Language

Copyright © Michael Stubbs 2008. This article is slightly revised from chapter 5, pp.83-97, of Michael Stubbs (1986) Educational Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. WHAT IS STANDARD ENGLISH? Introduction In Britain, Standard English is a central issue of language in education, since Standard English is a variety of language which can be defined only by reference to its role in the education system. It is also an example of a topic which requires careful conceptual analysis, since there is enormous confusion about terms such as 'standard', 'correct', 'proper', 'good', 'grammatical' or 'academic' English, and such terms are at the centre of much debate over English in education. A major role for linguistics is the steady unpicking of unreflecting beliefs and myths about language, especially where such beliefs affect the lives of all children in schools. Topics in language in education must be approached from four directions. 1. We need a technical linguistic description of the forms of Standard English: for example, its syntax. 2. We need a sociolinguistic theory to explain its functions: how and when it is used. 3. We need an applied analysis of planning and policy: for example, how it should be taught. 4. And we require an ideological analysis of Standard English as a major factor in the ways in which people experience power and control in their lives. Standard English has to do with passing exams, getting on in the world, respectability, prestige and success. Anyone who expresses such perceptions is also expressing an awareness of the ways in which Standard English reflects the historical and social forces which created and maintain it. -

English in Australia and New Zealand

English in Australia and New Zealand James Dixon, Narrative of a Voyage to New South Wales and Van Dieman’s Land in the Ship Skelton During the Year 1820 (1822) The children born in these colonies, and now grown up, speak a better language, purer, more harmonious, than is generally the case in most parts of England. The amalgamation of such various dialects assembled together, seems to improve the mode of articulating the words. Valerie Desmond, The Awful Australian (1911) But it is not so much the vagaries of pronunciation that hurt the ear of the visitor. It is the extraordinary intonation that the Australian imparts to his phrases. There is no such thing as cultured, reposeful conversation in this land; everybody sings his remarks as if he were reciting blank verse after the manner of an imperfect elocutionist. It would be quite possible to take an ordinary Australian conversation and immortalise its cadences and diapasons by means of musical notation. Herein the Australian differs from the American. The accent of the American, educated and uneducated alike, is abhorrent to the cultured Englishman or Englishwoman, but it is, at any rate, harmonious. That of the Australian is full of discords and surprises. His voice rises and falls with unexpected syncopations, and, even among the few cultured persons this country possesses, seems to bear in every syllable the sign of the parvenu. Walter Churchill (of the American Philological Society) The common speech of the commonwealth of Australia represents the most brutal maltreatment which has ever been inflicted upon the mother tongue of the English-speaking nations. -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

A Study of British Migration to Western Australia in the 1960S, with Special Emphasis on Those Who Travelled on the SS Castel Felice

University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2007 From Dream to Reality: A study of British migration to Western Australia in the 1960s, with special emphasis on those who travelled on the SS Castel Felice Hilda June Caunt University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The am terial in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Caunt, H. J. (2007). From Dream to Reality: A study of British migration to Western Australia in the 1960s, with special emphasis on those who travelled on the SS Castel Felice (Master of Arts (MA)). University of Notre Dame Australia. http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/34 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter Five ‘‘‘It‘It was even better than they advertisedadvertised’’’’ Settling in to life in Western Australia In such promotional material distributed in Britain as ‘Australia invites you’, prospective migrants were promised a ‘British way of life’ in Australia, social security, a healthy lifestyle, and, indeed a better standard of living ‘among the highest in the world’.1 Immigration propaganda was certainly persuasive; so much so that Knightley suggests the Australian government offered bribes to the British immigrants.2 But the promise of a better life looked for many, on arrival, to be unattainable.