The Vocabulary of Australian English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

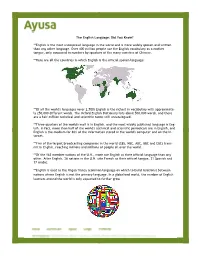

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Stewcockatoo Internals 19.Indd 1 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM

StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 1 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 2-3 17/6/10 7:09:24 PM W r i t t e n b y R u t h i e M a y I l l u s t r a t e d b y L e i g h H O B B S Stew a Cockatoo My Aussie Cookbook StewCockatoo_Internals_19.indd 4-5 17/6/10 7:09:30 PM Table of Contents 4 Cooee, G’Day, Howya Goin’? 22 The Great Aussie Icon We Australians love our slang. ‘Arvo : Dinky-di Meat Pie tea’ sounds friendlier than ‘afternoon 5 Useful Cook’s Tools tea’ and ‘fair dinkum’ is more fun 24 Grandpa Bruce’s Great Aussie BBQ to say than ‘genuine’. This book is 6 ’Ave a Drink,Ya Mug! 26 It’s a Rissole, Love! jam-packed with Aussie slang. If you 8 The Bread Spread come across something you haven’t 28 Bangers, Snags and Mystery Bags heard before, don’t worry, now is your 10 Morning Tea for Lords chance to pick up some you-beaut lingo and Bush Pigs 30 Fish ’n’ Chips Down Under you can use with your mates. 12 Bikkies for the Boys 32 Bush Tucker 14 Arvo Tea at Auntie Beryl’s 34 From Over Yonder to Down Under 16 From the Esky 36 Dessert Dames For Norm Corker - the best sav stew maker 18 Horse Doovers 38 All Over, Pavlova in all of Oz. On ya, Gramps!-RM 20 Whacko the Chook! 40 Index Little Hare Books an imprint of Hardie Grant Egmont 85 High Street Cooee, g’day, Prahran, Victoria 3181, Australia www.littleharebooks.com howya goin’? Copyright © text Little Hare Books 2010 Copyright © illustrations Leigh Hobbs 2010 Text by Ruthie May First published 2010 All rights reserved. -

Pinja-Kurlu Pinja-Kurlu

Pinja-kurlu Pinja-kurlu Yimi ngarrumu Victor Simon Jupurrurlarlu manu Maggie Blacksmith Napangardirli Yirramu pipa-kurra manu kuruwarri kujumu Rhonda Samuels Napurrurlarlu Jungami-manu Valerie Patterson Napanangkarlu Lajamanu CEC Literacy Centre 2001 Warlpiri ISBN: 1 920752 14 5 1 Wangkami ka Victor Simon Jupurrurla: Nyampu yarturlu kuja kama mardami ngulaji nyampu-wardingki nyampu-jangka. Ngula kalalu ngunju-manu manganiji manangkarra-wardingki, nyampuju kalalu yirdi-manu ngurlu, kalalu puyupungu pamanpa-jarra kurlurlu. Ngulajangka kalalu ngunju-manu mangarrilki. 2 Panu-jarlu kalalu nyinaja yapaju nyampurlaju kalalu warru-wapaja jalya-nyayimi wiyarrpa kurdu-kurdu, manu wiri-wiri. Ngulajangka kardiyalku yanumu kawartawararla. Kardiya yanu nguru-kari-kirra tamngalku kuja yalirra-wana palijalku. 3 Nyampurra-piya kalalu ngurrju-manu mangarriji mungalyurru, karlarlarla, manu wuraji-wurajirla. Kalalu-jana ngunju-manu mangarriji warlungka. Ngulajangkajuku kalalu ngamu mangarriji. 4 Nyampu nguruju ngulaji ka nyinami warlu jukurrpa. Yali kanpa nyanyi warlu, ngula-piya kala jankaja, kala wantija yimtiji nyampu-kurraju. Warlu-jangka kala warlpangku kujumu yimtiji. Jankajalpa warluju wiri-jarlu nyampurra-wana, karlaira-pura tarnnga-juku Ringer Soak-wana. Nyampu-wana-jangka ngula yanu Pinja-jangka wiri-jarlu-nyayimi warluju wantiki yinya-wana Tanami- Highway-wana, ngula-wana ngulalpa warluju jankaja. 5 Wangkamilki ka Maggie Blacksmith Napangardi: Nyampuju nguirara ngaju-nyangu warringiyi-kirlangu manu jamirdi-kirlangu. Nyampu kula ka nyina walya, walku, nyampuju ngayi kamalu wapami nganimpa kankarlumparralku, kurdu-kurdu wamulku kamalu wapami nyampurlaju mukulu wantija. Manulu-jana muku luwamu. 6 Kardiyalpalu nyampurlaju warru-wapaja kawartawara-kurlu kujalu ngunju-manu yardi nyampurla manu mulju-piya ngapa-kurlu. Kardiyarlu pangumulpalu nyampu kankalarra pirli. Kuja yimti wantija Malungurru- jangka. 7 Pirlingkilpalu yurrpamu ngurlu. -

Origins of NZ English

Origins of NZ English There are three basic theories about the origins of New Zealand English, each with minor variants. Although they are usually presented as alternative theories, they are not necessarily incompatible. The theories are: • New Zealand English is a version of 19th century Cockney (lower-class London) speech; • New Zealand English is a version of Australian English; • New Zealand English developed independently from all other varieties from the mixture of accents and dialects that the Anglophone settlers in New Zealand brought with them. New Zealand as Cockney The idea that New Zealand English is Cockney English derives from the perceptions of English people. People not themselves from London hear some of the same pronunciations in New Zealand that they hear from lower-class Londoners. In particular, some of the vowel sounds are similar. So the vowel sound in a word like pat in both lower-class London English and in New Zealand English makes that word sound like pet to other English people. There is a joke in England that sex is what Londoners get their coal in. That is, the London pronunciation of sacks sounds like sex to other English people. The same joke would work with New Zealanders (and also with South Africans and with Australians, until very recently). Similarly, English people from outside London perceive both the London and the New Zealand versions of the word tie to be like their toy. But while there are undoubted similarities between lower-class London English and New Zealand (and South African and Australian) varieties of English, they are by no means identical. -

Etytree: a Graphical and Interactive Etymology Dictionary Based on Wiktionary

Etytree: A Graphical and Interactive Etymology Dictionary Based on Wiktionary Ester Pantaleo Vito Walter Anelli Wikimedia Foundation grantee Politecnico di Bari Italy Italy [email protected] [email protected] Tommaso Di Noia Gilles Sérasset Politecnico di Bari Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS Italy Grenoble INP, LIG, F-38000 Grenoble, France [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT a new method1 that parses Etymology, Derived terms, De- We present etytree (from etymology + family tree): a scendants sections, the namespace for Reconstructed Terms, new on-line multilingual tool to extract and visualize et- and the etymtree template in Wiktionary. ymological relationships between words from the English With etytree, a RDF (Resource Description Framework) Wiktionary. A first version of etytree is available at http: lexical database of etymological relationships collecting all //tools.wmflabs.org/etytree/. the extracted relationships and lexical data attached to lex- With etytree users can search a word and interactively emes has also been released. The database consists of triples explore etymologically related words (ancestors, descendants, or data entities composed of subject-predicate-object where cognates) in many languages using a graphical interface. a possible statement can be (for example) a triple with a lex- The data is synchronised with the English Wiktionary dump eme as subject, a lexeme as object, and\derivesFrom"or\et- at every new release, and can be queried via SPARQL from a ymologicallyEquivalentTo" as predicate. The RDF database Virtuoso endpoint. has been exposed via a SPARQL endpoint and can be queried Etytree is the first graphical etymology dictionary, which at http://etytree-virtuoso.wmflabs.org/sparql. -

Multilingual Ontology Acquisition from Multiple Mrds

Multilingual Ontology Acquisition from Multiple MRDs Eric Nichols♭, Francis Bond♮, Takaaki Tanaka♮, Sanae Fujita♮, Dan Flickinger ♯ ♭ Nara Inst. of Science and Technology ♮ NTT Communication Science Labs ♯ Stanford University Grad. School of Information Science Natural Language ResearchGroup CSLI Nara, Japan Keihanna, Japan Stanford, CA [email protected] {bond,takaaki,sanae}@cslab.kecl.ntt.co.jp [email protected] Abstract words of a language, let alone those words occur- ring in useful patterns (Amano and Kondo, 1999). In this paper, we outline the develop- Therefore it makes sense to also extract data from ment of a system that automatically con- machine readable dictionaries (MRDs). structs ontologies by extracting knowledge There is a great deal of work on the creation from dictionary definition sentences us- of ontologies from machine readable dictionaries ing Robust Minimal Recursion Semantics (a good summary is (Wilkes et al., 1996)), mainly (RMRS). Combining deep and shallow for English. Recently, there has also been inter- parsing resource through the common for- est in Japanese (Tokunaga et al., 2001; Nichols malism of RMRS allows us to extract on- et al., 2005). Most approaches use either a special- tological relations in greater quantity and ized parser or a set of regular expressions tuned quality than possible with any of the meth- to a particular dictionary, often with hundreds of ods independently. Using this method, rules. Agirre et al. (2000) extracted taxonomic we construct ontologies from two differ- relations from a Basque dictionary with high ac- ent Japanese lexicons and one English lex- curacy using Constraint Grammar together with icon. -

AUSTRALIAN FOOD SLANG Abstract

UNIWERSYTET HUMANISTYCZNO-PRZYRODNICZY IM. JANA DŁUGOSZA W CZĘSTOCHOWIE Studia Neofilologiczne 2020, z. XVI, s. 151–170 http://dx.doi.org/10.16926/sn.2020.16.08 Dana SERDITOVA https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1206-8507 (University of Heidelberg) AUSTRALIAN FOOD SLANG Abstract The article analyzes Australian food slang. The first part of the research deals with the definition and etymology of the word ‘slang’, the purpose of slang and its main characteristics, as well as the history of Australian slang. In the second part, an Australian food slang classification consisting of five categories is provided: -ie/-y/-o and other abbreviations, words that underwent phonetic change, words with new meaning, Australian rhyming slang, and words of Australian origin. The definitions of each word and examples from the corpora and various dictionaries are provided. The paper also dwells on such particular cases as regional varieties of the word ‘sausage’ (including the map of sausages) and drinking slang. Keywords: Australian food slang, Australian English, varieties of English, linguistic and culture studies. Australian slang is a vivid and picturesque part of an extremely fascinating variety of English. Just like Australian English in general, the slang Down Under is influenced by both British and American varieties. Australian slang started as a criminal language, it moved to Australia together with the British convicts. Naturally, the attitude towards slang was negative – those who were not part of the criminal culture tried to exclude slang words from their vocabulary. First and foremost, it had this label of criminality and offense. This attitude only changed after the World War I, when the soldiers created their own slang, parts of which ended up among the general public. -

1/4 Here You Can Find an Overview of the 50 Must

Here you can find an overview of the 50 must-know British slang words and phrases. Print out this PDF document and practice them with your British Tandem partner: Bloke “Bloke” would be the American English equivalent of “dude.” It means a “man.” Lad In the same vein as “bloke,” “lad” is used, however, for boys and younger men. Bonkers Not necessarily intended in a bad way, “bonkers” means “mad” or “crazy.” Daft Used to mean if something is a bit stupid. It’s not particularly offensive, just mildly silly or foolish. To leg it This term means to run away, usually from some trouble! “I legged it from the Police.” These two words are British slang for drunk. One can get creative here Trollied / Plastered and just add “-ed” to the end of practically any object to get across the same meaning eg. hammered. Quid This is British slang for British pounds. Some people also refer to it as “squid.” Used to describe something or someone a little suspicious or Dodgy questionable. For example, it can refer to food which tastes out of date or, when referring to a person, it can mean that they are a bit sketchy. This is a truly British expression. “Gobsmacked” means to be utterly Gobsmacked shocked or surprised beyond belief. “Gob” is a British expression for “mouth”. Bevvy This is short for the word “beverages,” usually alcoholic, most often beer. Knackered “Knackered” is used when someone is extremely tired. For example, “I was up studying all night last night, I’m absolutely knackered.” Someone who has “lost the plot” has become either angry, irrational, Lost the plot or is acting ridiculously. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Not Taking Yourself Too Seriously in Australian English: Semantic Explications, Cultural Scripts, Corpus Evidence

Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence Author Goddard, Cliff Published 2009 Journal Title Intercultural Pragmatics Version Version of Record (VoR) DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/IPRG.2009.002 Copyright Statement © 2009 Walter de Gruyter & Co. KG Publishers. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/44428 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Not taking yourself too seriously in Australian English: Semantic explications, cultural scripts, corpus evidence CLIFF GODDARD Abstract In the mainstream speech culture of Australia (as in the UK, though per- haps more so in Australia), taking yourself too seriously is culturally proscribed. This study applies the techniques of Natural Semantic Meta- language (NSM) semantics and ethnopragmatics (Goddard 2006b, 2008; Wierzbicka 1996, 2003, 2006a) to this aspect of Australian English speech culture. It first develops a semantic explication for the language-specific ex- pression taking yourself too seriously, thus helping to give access to an ‘‘in- sider perspective’’ on the practice. Next, it seeks to identify some of the broader communicative norms and social attitudes that are involved, using the method of cultural scripts (Goddard and Wierzbicka 2004). Finally, it investigates the extent to which predictions generated from the analysis can be supported or disconfirmed by contrastive analysis of Australian English corpora as against other English corpora, and by the use of the Google search engine to explore di¤erent subdomains of the World Wide Web.