Good Distribution, Bad Delivery, and Ugly Politics: The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei Gegenüber Dem

1 2 3 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei gegenüber dem 4 Nationalsozialismus und dem Reichskonkordat 1930–1933: 5 Motivationsstrukturen und Situationszwänge* 6 7 Von Winfried Becker 8 9 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei wurde am 13. Dezember 1870 von ca. 50 Man- 10 datsträgern des preußischen Abgeordnetenhauses gegründet. Ihre Reichstagsfrak- 11 tion konstituierte sich am 21. März 1871 beim Zusammentritt des ersten deut- 12 schen Reichstags. 1886 vereinigte sie sich mit ihrem bayerischen Flügel, der 1868 13 eigenständig als Verein der bayerischen Patrioten entstanden war. Am Ende des 14 Ersten Weltkriegs, am 12. November 1918, verselbständigte sich das Bayerische 15 Zentrum zur Bayerischen Volkspartei. Das Zentrum verfiel am 5. Juli 1933 der 16 Selbstauflösung im Zuge der Beseitigung aller deutschen Parteien (außer der 17 NSDAP), ebenso am 3. Juli die Bayerische Volkspartei. Ihr war auch durch die 18 Gleichschaltung Bayerns und der Länder der Boden entzogen worden.1 19 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei der Weimarer Republik war weder mit der 20 katholischen Kirche dieser Zeit noch mit dem Gesamtphänomen des Katho- 21 lizismus identisch. 1924 wählten nach Johannes Schauff 56 Prozent aller Ka- 22 tholiken (Männer und Frauen) und 69 Prozent der bekenntnistreuen Katholiken 23 in Deutschland, von Norden nach Süden abnehmend, das Zentrum bzw. die 24 Bayerische Volkspartei. Beide Parteien waren ziemlich beständig in einem 25 Wählerreservoir praktizierender Angehöriger der katholischen Konfession an- 26 gesiedelt, das durch das 1919 eingeführte Frauenstimmrecht zugenommen hat- 27 te, aber durch die Abwanderung vor allem der männlichen Jugend von schlei- 28 chender Auszehrung bedroht war. Politisch und parlamentarisch repräsentierte 29 die Partei eine relativ geschlossene katholische »Volksminderheit«.2 Ihre re- 30 gionalen Schwerpunkte lagen in Bayern, Südbaden, Rheinland, Westfalen, 31 32 * Erweiterte und überarbeitete Fassung eines Vortrags auf dem Symposion »Die Christ- 33 lichsozialen in den österreichischen Ländern 1918–1933/34« in Graz am 4. -

Adam Stegerwald Und Die Krise Des Deutschen Parteiensystems. Ein

VIERTELJAHRSHEFTE FÜR ZEITGESCHICHTE 27. Jahrgang 1979 Heft 1 LARRY EUGENE JONES ADAM STEGERWALD UND DIE KRISE DES DEUTSCHEN PARTEIENSYSTEMS Ein Beitrag zur Deutung des „Essener Programms" vom November 1920* Die Auflösung des bürgerlichen Parteiensystems war in der Weimarer Republik bereits weit fortgeschritten, als die Weltwirtschaftskrise in den frühen 30er Jah ren mit voller Intensität über Deutschland hereinbrach und die Nationalsoziali stische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei ihren entscheidenden Einbruch in die deutschen Mittelparteien erzielte. Der Anfang der Weltwirtschaftskrise und der Aufstieg des Nationalsozialismus haben die Auflösung des Weimarer Parteiensystems zweifellos beschleunigt, doch lag ihre Hauptwirkung darin, Auflösungstendenzen zu verstärken, die bereits bei der Entstehung der Weimarer Republik vorhanden waren. Parteipolitisch gesehen, hing also das Schicksal der Weimarer Republik weitgehend davon ab, ob es den Parteien der sogenannten bürgerlichen Mitte - insbesondere der Deutschen Zentrumspartei, der Deutschen Demokratischen Par tei (DDP) und der Deutschen Volkspartei (DVP) - gelang, die verschiedenen Sozial- und Berufsgruppen, die die deutsche Mittelschicht bildeten, zusammen mit den nichtsozialistischen Teilen der deutschen Arbeiterschaft zu einem lebens fähigen und schlagkräftigen politischen Machtfaktor zu integrieren. Eine starke Mitte hätte die spätere Polarisierung des deutschen Parteiensystems und den dadurch ermöglichten Aufstieg des Nationalsozialismus vermutlich aufhalten können. Jedoch zeigten die deutschen -

Christliche Demokratie in Deutschland

Christliche Demokratie in Deutschland Winfried Becker Geschichtserzählungen können bekanntlich vielen Er- kenntniszielen dienen. Nicht nur Staaten, sondern auch Na- tionen übergreifende Großgruppen bilden ein Gedächtnis aus, bauen ein Erinnerungsvermögen auf. Durch den Blick in ihre Vergangenheit gewinnen sie Aufschlüsse über ihre Herkunft und ihre Identität. Dabei muss die Fragemethode dem Sujet, dem Gegenstand gerecht werden, den sie aller- dings selbst gewissermaßen mit konstituiert. Die Ge- schichte der an christlichen Wertmaßstäben (mit-)orientier- ten politischen und sozialen Kräfte in Deutschland kann zureichend weder aus der nationalliberalen Sichtweise des 19. Jahrhunderts noch mit den ökonomischen Begriffen der marxistischen Klassenanalyse erfasst werden. Sie wurzelte im politischen Aufbruch der katholischen Minderheit. De- ren Etikettierung als „reichsfeindlich“, national unzuver- lässig, „ultramontan“ und „klerikal“, d. h. unzulässig ins politische Gebiet eingreifend, entsprang nationalliberalen Sichtweisen, wurde vom Nationalsozialismus rezipiert und wirkte wohl unbewusst darüber hinaus.1 Auf die Dauer konnte sich aber in einem pluralistischer werdenden Geschichtsbewusstsein eine so einspännige Be- trachtungsweise nicht halten. Aus internationaler Perspek- tive stellt sich die katholische Bewegung heute eher facet- tenreich und durchaus politikrelevant dar. Sie entfaltete in ihren Beziehungen zur römischen Kurie und zu den be- nachbarten christlichen Konfessionen eine kirchenge- schichtliche Dimension. Sie zeigte ideengeschichtliche -

Anti-Semitic Propaganda and the Christian Church in Hitler's Germany

Advances in Historical Studies, 2018, 7, 1-14 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs ISSN Online: 2327-0446 ISSN Print: 2327-0438 Anti-Semitic Propaganda and the Christian Church in Hitler’s Germany: A Case of Schrödinger’s Cat Angelo Nicolaides School of Business Leadership, University of South Africa, Midrand, South Africa How to cite this paper: Nicolaides, A. Abstract (2018). Anti-Semitic Propaganda and the Christian Church in Hitler’s Germany: A In his epic Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler made a point of disparaging the intelli- Case of Schrödinger’s Cat. Advances in gentsia. He asserted that propaganda was the most effective tool to use in po- Historical Studies, 7, 1-14. litical campaigns since especially the popular masses generally possessed li- https://doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2018.71001 mited astuteness and were generally devoid of intellect. This article examines Received: December 5, 2017 the part played by Nazi propaganda in bolstering the National Socialist cause Accepted: March 13, 2018 and how it netted the German youth. Nazi indoctrination nurtured racial ha- Published: March 16, 2018 tred and resulted in especially vitriolic anti-Semitism. The policy of Gleich- schaltung (coordination) brought state governments, professional bodies, Copyright © 2018 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. German political parties and a range of cultural bodies under the Nazi um- This work is licensed under the Creative brella, thus education, legal systems and the entire economy became “cap- Commons Attribution International tured” entities. Germany became dominated by the effective propaganda ma- License (CC BY 4.0). chine via which virtually all aspects of life was dictated. -

The German Center Party and the League of Nations: International Relations in a Moral Dimension

InSight: RIVIER ACADEMIC JOURNAL, VOLUME 4, NUMBER 2, FALL 2008 THE GERMAN CENTER PARTY AND THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS: INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN A MORAL DIMENSION Martin Menke, Ph.D.* Associate Professor, Department of History, Law, and Political Science, Rivier College During the past two decades, scholarly interest in German political Catholicism, specifically in the history of the German Center Party has revived.1 As a spate of recent publication such as Stathis Kalyvas’s The Rise of Christian Democracy in Europe and the collection of essays, Political Catholicism in Europe, 1918-1965, 2 show, this renewed interest in German political Catholicism is part of a larger trend. All of these works, however, show how much work remains to be done in this field. While most research on German political Catholicism has focused on the period before 1918, the German Center Party’s history during the Weimar period remains incompletely explored. One of the least understood areas of Center Party history is its influence on the Weimar government’s foreign policy. After all, the Center led nine of the republic’s twenty cabinets. Karsten Ruppert, for example, relies almost exclusively on Peter Krüger’s Die Außenpolitik der Republik von Weimar,3 which emphasizes the role of Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann almost to the exclusion of all other domestic decision-makers. Weimar’s foreign policy largely consisted of a series of responses to crises caused by political and economic demands made by the victors of the First World War. These responses in turn were determined by the imperatives of German domestic politics. -

Mommsen, Hans, Germans Against Hitler

GERMANS AGAINST HITLER HANS MOMMSEN GERMANSGERMANSGERMANS AGAINSTAGAINST HITLERHITLER THE STAUFFENBERG PLOT AND RESISTANCE UNDER THE THIRD REICH Translated and annotated by Angus McGeoch Introduction by Jeremy Noakes New paperback edition published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com First published in hardback in 2003 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd as Alternatives to Hitler. Originally published in 2000 as Alternative zu Hitler – Studien zur Geschichte des deutschen Widerstandes. Copyright © Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munchen, 2000 Translation copyright © I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2003, 2009 The translation of this work has been supported by Inter Nationes, Bonn. The right of Hans Mommsen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 852 5 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library Project management by Steve Tribe, Andover Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press India Ltd ContentsContentsContents Preface by Hans Mommsen vii Introduction by Jeremy Noakes 1 1. Carl von Ossietzky and the concept of a right to resist in Germany 9 2. German society and resistance to Hitler 23 3. -

German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Zetsche, Anne (2016) The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/31606/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974 Anne Zetsche PhD 2016 The Quest for Atlanticism: German-American Elite Networking, the Atlantik-Brücke and the American Council on Germany, 1952-1974 Anne Zetsche, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Department of Humanities August 2016 Abstract This work examines the role of private elites in addition to public actors in West German- American relations in the post-World War II era and thus joins the ranks of the “new diplomatic history” field. -

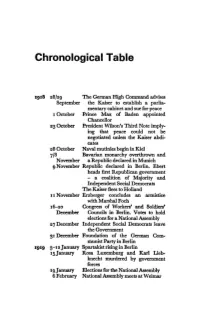

Chronological Table

Chronological Table 1918 28/29 The German High Command advises September the Kaiser to establish a parlia mentary cabinet and sue for peace 1 October Prince Max of Baden appointed Chancellor 23 October President Wilson's Third Note imply ing that peace could not be negotiated unless the Kaiser abdi cates 28 October Naval mutinies begin in Kiel 7/8 Bavarian monarchy overthrown and November a Republic declared in Munich 9 November Republic declared in Berlin. Ebert heads first Republican government - a coalition of Majority and Independent Social Democrats The Kaiser flees to Holland I I November Erzberger concludes an armistice with Marshal Foch 16-20 Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' December Councils in Berlin. Votes to hold elections for a National Assembly 27 December Independent Social Democrats leave the Government 31 December Foundation of the German Com munist Party in Berlin 1919 5-12january SpartakistrisinginBerlin 15january Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Lieb knecht murdered by government forces Igjanuary Elections for the National Assembly 6 February National Assembly meets at Weimar 174 CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE 7 April Bavarian Soviet Republic proclaimed in Munich 1May Bavarian Soviet suppressed by Reichs wehr and Bavarian Freikorps 28june Treaty of Versailles signed II August The Constitution of the German Republic formally promulgated 2I August Friedrich Ebert takes the oath as President September Hitler joins the German Workers' Party in Munich 1920 24 February Hitler announces new programme of the National Socialist German Workers Party (formally German Workers' Party) 13 March Kapp Putsch. Ebert and Ininisters flee to Stuttgart 17March Collapse of Putsch 24March Defence Minister Noske and army chief Reinhardt resign. -

William L. Patch the William R

William L. Patch The William R. Kenan Professor of History Washington and Lee University 204 West Washington Street Lexington, VA 24450 e-mail: [email protected] Office telephone: 540-458-8774 Fax: 540-458-8498 Education 1975-1981 Yale University New Haven, CT Ph.D. in German Social and Political History, 1848-1945 ▪ Related minor field: European cultural history, 1860-1930 ▪ Unrelated minor field: Reformation Europe, 1500-1648 1971-1975 University of California Berkeley, CA B.A. with Great Distinction ▪ Graduated with High Honors in the History Major ▪ Studied at the University of Göttingen in 1973-74 Academic Honors & Fellowships Appointed the William R. Kenan Professor of History at 2006 Washington and Lee University National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship for 1999-2000 Independent Study and Research 1989 Helena Percas de Ponseti Research Scholar 1979-1980 Charles A. Whiting Fellow 1978-1979 German Academic Exchange Fellow 1975-1978 Yale University Fellow 1975 Elected to Phi Beta Kappa Teaching Experience Since 2006 Washington and Lee University Lexington, VA The William R. Kenan Professor of History, teaching: ▪ Introductory surveys of modern Europe, and intermediate courses on German history and the history of international relations since 1800 ▪ Advanced undergraduate seminars on “Nazism and the Third Reich” and “The Great War in History and Literature” 1 William L. Patch 1985-2006 Grinnell College Grinnell, IA Professor of History, 1998-2005 Associate Professor of History, 1989-1998 Assistant Professor of History, 1985-1989 -

The German Center Party and the Reichsbanner

THOMAS A. KNAPP THE GERMAN CENTER PARTY AND THE REICHSBANNER A CASE STUDY IN POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CONSENSUS IN THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The problem of paramilitary organizations in Germany after 1918 forms an interesting and crucial chapter in the story of the ill-fated Weimar Republic. The organizations which gained the most notoriety stood on the far political right, unreconciled and unreconcilable both to military defeat and to the republic which was the child of that defeat. But the republic did have its militant defenders, who were recruited on the democratic left and organized in the Reichsbanner.1 The history of the Reichsbanner not only vividly demonstrated "the sharpness of political antagonisms"2 in the republic, but also reflected several developments during Germany's so-called golden years after 1924: the balance of political forces, Catholic-socialist and bourgeois- socialist relations, and in no small degree the disintegration of the Weimar Coalition (Social Democratic Party, Democratic Party, and Center Party). It is felt that the relationship between the Reichsbanner and the Center party can be treated as one important test case of political and social stability in Germany during the 1920's. Apart from the size and relative electoral stability of the Center, and the potential contribution it could make to the Reichsbanner, this question had some far-reaching ramifications. At least three interconnected problems were brought into play, namely, unresolved social tensions inherited from pre-war Germany, the Center's attitude towards the republic, and the role of that party's republican left wing and its most outspoken representative, Joseph Wirth. -

Adam Stegerwald Und Die Große Koalition in Denanfangsjahren

Böhlau, Fr. Fichtner, Historisch-Politische-Mitteilungen, 1. AK, MS Ein christlich-nationaler Politiker zwischen Sammlung und Abgrenzung: Adam Stegerwald und die große Koalition in den Anfangsjahren der Weimarer Republik Von Bernhard Forster »Grundsätzlich kann es in dem Verhältnis zwischen dem Unternehmertum und den Arbeitern auch nur zweierlei geben: entweder Klassenkampf von unten und oben oder verstärkte Friedensbereitschaft in beiden Lagern. Alles andere ist Halbheit und bringt nur Verwirrung und Unsicherheit in beide Lager. Man redet seit vielen Wochen von einer großen Koalition in Deutschland. Große Koalition nach der politischen Seite hat nur einen Sinn, wenn auch nach der wirtschaftlichen Seite der Weg zur beiderseitigen Verständigungsbereitschaft resolut betreten wird. ... Wenn aber die Verständigungsbereitschaft auf wirt- schaftlichem Gebiete meinetwegen einstweilen nur für einige Jahre nicht zur Tat wird, dann schlagen wir praktisch wirtschaftlich das wieder entzwei, was wir politisch aufzubauen suchen.«1 Mit diesen Worten forderte Adam Steger- wald, Vorsitzender des Gesamtverbandes der christlichen Gewerkschaften Deutschlands und des »Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes« (DGB), namens der zu dieser Zeit von ihm kommissarisch geleiteten Zentrumsfraktion des Reichs- tags am 12. November 1928 die Parteien zur Bildung der großen Koalition von Zentrum, SPD, DDP und DVP auf, die von einem grundlegenden Ein- vernehmen zwischen den Wirtschaftsverbänden und den Gewerkschaften flan- kiert sein sollte. Bezweckte der Appell Stegerwalds konkret