Language Policy, Language Attitudes and Identity in Hong Kong Vian Yuen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-Accented English: a Phonetic Comparison

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 724-738, September 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1105.07 Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-accented English: A Phonetic Comparison Yunyun Ran School of Foreign Languages, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, 333 Long Teng Road, Shanghai 201620, China Jeroen van de Weijer School of Foreign Languages, Shenzhen University, 3688 Nan Hai Avenue, Shenzhen 518060, China Marjoleine Sloos Fryske Akademy (KNAW), Doelestrjitte 8, 8911 DX Leeuwarden, The Netherlands Abstract—Hong Kong English is to a certain extent a standardized English variety spoken in a bilingual (English-Cantonese) context. In this article we compare this (native) variety with English as a foreign language spoken by other Cantonese speakers, viz. learners of English in Guangzhou (mainland China). We examine whether the notion of standardization is relevant for intonation in this case and thus whether Hong Kong English is different from Cantonese English in a wider perspective, or whether it is justified to treat Hong Kong English and Cantonese English as the same variety (as far as intonation is concerned). We present a comparison between intonational contours of different sentence types in the two varieties, and show that they are very similar. This shows that, in this respect, a learned foreign-language variety can resemble a native variety to a great extent. Index Terms—Hong Kong English, Cantonese-accented English, intonation I. INTRODUCTION Cantonese English may either refer to Hong Kong English (HKE), or to a broader variety of English spoken in the Cantonese-speaking area, including Guangzhou (Wong et al. -

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

Download Our Latest Allegravita Backgrounder Booklet Here (PDF)

Name: Allegravita is an award-winning, multi- disciplinary public relations and strategic communications agency focused on supporting international clients in the China region and taking Chinese clients to the world. We were voted China's most entrepreneurial company by the Australian Chambers of ABOUT ALLEGRAVITA Commerce in China in 2008. Allegravita is a boutique global agency A PORTFOLIO OF SERVICES TO BORN IN CHINA, with personnel and offices in Beijing, HELP YOU SUCCEED IN CHINA EFFECTIVE WORLDWIDE Guangzhou, Kunming, Hong Kong, Public Relations for proactive and Although our focus is on the China New York City and San Francisco. Since reactive messaging. region, our services are very effective 2003 we have provided high-quality Marketing and Communications in markets worldwide, with proven PR, marketing and corporate advisory Collateral to present your messages outcomes. Allegravita works within services with a special focus on achiev- with excellent credibility. a highly-accountable and disciplined ing excellent results for international Media Relations & Media Training Western management style, executing clients in the China region and in Chi- to insert your messages into Chinese the highest quality of work for our nese speaking markets worldwide, and and international media in the most clients, which we deliver with agility, international results for our Chinese compelling way possible. flexibility, creativity and cultural savvy. clients. Corporate Identity localization to Allegravita is an ethnically diverse, We incorporate expert public relations communicate your brand values and multi-cultural team of professionals abilities with a firm grasp of contempo- benefits to Chinese markets, and for of different cultural heritages. What rary China-region marketplaces to help Chinese clients, to international inves- we share in common is our passion for our clients communicate effectively, tors and influencers. -

Cifu: a Frequency Lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 3069–3077 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Cifu: a frequency lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese Regine Lai, Grégoire Winterstein The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Université du Québec à Montréal Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, Département de Linguistique [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper introduces Cifu, a lexical database for Hong Kong Cantonese (HKC) that offers phonological and orthographic information, frequency measures, and lexical neighborhood information for lexical items in HKC. The resource can be used for NLP applications and the design and analysis of psycholinguistic experiments on HKC. We elaborate on the characteristics and challenges specific to HKC that were relevant in the design of Cifu. This includes lexical, orthographic and phonological aspects of HKC, word segmentation issues, the place of HKC in written media, and the availability of data. We discuss the measure of Neighborhood Density (ND), highlighting how the analytic nature of Cantonese and its writing system affect that measure. We justify using six different variations of ND, based on the possibility of inserting or deleting phonemes when searching for neighbors and on the choice of data for retrieving frequencies. Statistics about the four genres (written, adult spoken, children spoken and child-directed) within the dataset are discussed. We find that the lexical diversity of the child-directed speech genre is particularly low, compared to a size-matched written corpus. The correlations of word frequencies of different genres are all high, but in general decrease as word length increases. -

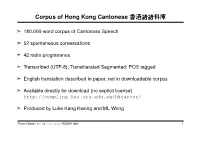

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港港港語語語語語語料料料庫庫庫

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港nn;;;;;;$$$庫庫庫 ã 180,000-word corpus of Cantonese Speech ã 52 spontaneous conversations ã 42 radio programmes ã Transcribed (UTF-8); Transliterated Segmented; POS tagged ã English translation described in paper, not in downloadable corpus ã Available directly for download (no explicit license) http://compling.hss.ntu.edu.sg/hkcancor/ ã Produced by Luke Kang Kwong and ML Wong Francis Bond <[email protected]> HG3051 lab2 1 Creation ã 30 hours of recordings (March 1997 — August 1998) ã Native speakers of Cantonese ã ordinary settings with family members, friends and colleagues talking with each other freely on everyday topics such as current affairs, work and study, and personal hobbies ã Some parts selected 2 Meta-Data/Annotation ã Meta-Data Tape number (of recording); Date of recording Number of Speakers; List of Speakers (Code-Sex-Age-Origin) (e.g. A-M-22-HK says A is a 22-year-old male speaker from Hong Kong) ã Annotation Each Utterance has the speaker code Utterances are segmented, POS tagged and transliterated Ç%h/d/ge3i1bun2soeng6/ 2個/r/ni1go3/ze ... ã The whole corpus is wrapped in xml (but not very well) 3 Usage ã Used to examine the uses of the frequently used sentence final particles woˇ and boˇ in the 1990s in Hong Kong Cantonese by examining speech data. ã Question: are woˇ (喎) and boˇ (S) variant forms? ã Answer: No “[. ] the two SFPs carry and serve different meanings and functions in modern Hong Kong Cantonese, and thus they are not exactly the same particles and not interchangeable as previously assumed.” (Leung, 2010, p21) ã Also used as a corpus in the PyCantonese Project: Working with Cantonese corpus data using Python, by Jackson L. -

The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname Under New Migration

CHAPTER 9 They Might as Well Be Speaking Chinese: The Changing Chinese Linguistic Situation in Suriname under New Migration Paul B. Tjon Sie Fat 1 Introduction This chapter presents one of the most obvious local examples, to the Surinamese public at least, of the link between mobility, language, and iden- tity: current Chinese migration. These ‘New Chinese’ migrants since the 1990s were linguistically quite different from the established Hakkas in Suriname, and were the cause of an upsurge in anti-Chinese sentiments. It will be argued that the aforementioned link is constructed in the Surinamese imagination in the context of ethnic and civic discourse to reproduce the image of a mono- lithic, undifferentiated, Chinese migrant group, despite increasing variety and change within the Chinese segment of Surinamese society. The point will also be made that the Chinese stereotype affects the way demographic and linguis- tic data relating to Chinese are produced by government institutions. We will present a historic overview of the Chinese presence in Suriname, a brief eth- nographic description of Chinese migrant cohorts, followed by some data on written Chinese in Suriname. Finally we present the available data on Chinese ethnicity and language from the Surinamese General Bureau of Statistics (abs). An ethnic Chinese segment has existed in Surinamese society since the middle of the nineteenth century, as a consequence of Dutch colonial policy to import Asian indentured labour as a substitute for African slave labour. Indentured labourers from Hakka villages in the Fuitungon Region (particu- larly Dongguan and Baoan)1 in the second half of the nineteenth century made way for entrepreneurial chain migrants up to the first half of the twentieth 1 The established Hakka migrants in Suriname refer to the area as fui5tung1on1 (惠東安), which is an anagram of the Kejia pronunciation of the names of the three counties where the ‘Old Chinese’ migrant cohorts in Suriname come from: fui5jong2 (惠陽 Putonghua: huìyáng), tung1kon1 (東莞 pth: dōngguǎn), and pau3on1 (寳安 pth: bǎoān). -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

Rendering the Regional

Rendering the Regional Rendering the Regional LOCAL LANGUAGE IN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE MEDIA Edward M.Gunn University of Hawai`i Press Honolulu Publication of this book was aided by the Hull Memorial Publication Fund of Cornell University. ( 2006 University of Hawai`i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 111009080706654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gunn, Edward M. Rendering the regional : local language in contemporary Chinese media / Edward M. Gunn. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2883-6 (alk. paper) 1. Language and cultureÐChina. 2. Language and cultureÐTaiwan. 3. Popular cultureÐChina. 4. Popular cultureÐTaiwan. I. Title. P35.5.C6G86 2005 306.4400951Ðdc22 2005004866 University of Hawai`i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by University of Hawai`i Press Production Staff Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Contents List of Maps and Illustrations /vi Acknowledgments / vii A Note on Romanizations /ix Introduction / 1 1 (Im)pure Culture in Hong Kong / 17 2 Polyglot Pluralism and Taiwan / 60 3 Guilty Pleasures on the Mainland Stage and in Broadcast Media / 108 4 Inadequacies Explored: Fiction and Film in Mainland China / 157 Conclusion: The Rhetoric of Local Languages / 204 Notes / 211 Sources Cited / 231 Index / 251 ±v± List of Maps and Illustrations Figure 1. Map showing distribution of Sinitic (Han) Languages / 2 Figure 2. Map of locations cited in the text / 6 Figure 3. The Hong Kong ®lm Cageman /42 Figure 4. Illustrated romance and pornography in Hong Kong / 46 Figure 5. -

Dana Scott Bourgerie Office Tel.: (801) 422-4952 E-Mail: [email protected] Website

Dana Scott Bourgerie Office Tel.: (801) 422-4952 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://bourgerie.byu.edu EDUCATION THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Columbus, Ohio. Ph.D. East Asian Languages and Literatures. 1990. Thesis: A Quantitative Study of Sociolinguistic Variation in Cantonese. THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Columbus, Ohio. M.A. East Asian Languages and Literatures. 1987. Thesis: Particles of Uncertainty: a Discourse Approach to the Cantonese Final Particle. UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Minneapolis, Minnesota. B.A. Linguistics and Chinese, Minor in French. 1982. ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE DEPARTMENT CHAIR. (June 2015-present). Asian and Near Eastern Languages, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. DIRECTOR. (January 2016-present). Cambodia Oral History Project. Humanities Center, BYU College of Humanities. VISITING PROFESSOR. (Fall 2014). Paññāsāstra University of Cambodia. College of Education. PROFESSOR. (2010-Present). Asian and Near Eastern Languages. Brigham Young University. DIRECTOR, NATIONAL CHINESE FLAGSHIP CENTER at Brigham Young University. Center for Language Studies and College of Humanities. (September 2002- August 2013). (National Security Education Program Grant). ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR. (1997-2010). Asian and Near Eastern Languages. Brigham Young University. ASSISTANT PROFESSOR. (1991-1997). Asian and Near Eastern Languages. Brigham Young University. LECTURER. (1990-91). Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures/The Center for Comparative Studies, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. RESEARCH ASSOCIATE. (3/89-6/90). East Asian Languages and Literatures, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. VISITING SCHOLAR. (1988-1989) Department of Anthropology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. LECTURER. (Winter and Fall terms 1988). Department of Languages, City Polytechnic of Hong Kong. PRINCIPAL INSTRUCTOR/TEACHING ASSOCIATE. (1983-1987). East Asian Languages and Literatures, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. -

Changes in the Language of Perception in Cantonese Hilário De

Changes in the language of perception in Cantonese Hilário de Sousa École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris, France 20100827 draft of: de Sousa, Hilário. 2011. Changes in the language of perception in Cantonese. Senses and Society6(1). 38–47. Do not quote or cite this draft. Changes in Cantonese 2 Biography Hilário de Sousa, formerly a postdoctoral researcher at the Language and Cognition Group at Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics, is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales. He has published on the morphosyntax of Papuan and Oceanic languages, and has recently started doing fieldwork on Southern Pinghua, a lesser-known Sinitic language spoken in Guangxi, China. Lexical semantics is his newest passion. [email protected]. Changes in Cantonese 3 Abstract The way a language encodes sensory experiences changes over time, and often this correlates with other changes in the society. There are noticeable differences in the language of perception between older and younger speakers of Cantonese in Hong Kong and Macau. Younger speakers make finer distinctions in the distal senses, but have less knowledge of the finer categories of the proximal senses than older speakers. The difference in the language of perception between older and younger speakers probably reflects the rapid changes that happened in Hong Kong and Macau in the last fifty years, from a under-developed and less-literate society, to a developed and highly- literate society. In addition to the increase in literacy, the education system has also undergone significant Westernization. Western-style education systems have most likely created finer categorizations in the distal senses. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES Hilary Chappell

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES Hilary Chappell To cite this version: Hilary Chappell. LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES. Alexandra Aikhenvald & RMW Dixon. Areal diffusion and genetic inheritance: problems for typology and genetic affiliation, Oxford University Press, pp.328-357, 2006, 0199283087. hal-00850205 HAL Id: hal-00850205 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00850205 Submitted on 5 Aug 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships.