Intonation in Hong Kong English and Guangzhou Cantonese-Accented English: a Phonetic Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Status of Cantonese in the Education Policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung*

Lee and Leung Multilingual Education 2012, 2:2 http://www.multilingual-education.com/2/1/2 RESEARCH Open Access The status of Cantonese in the education policy of Hong Kong Kwai Sang Lee and Wai Mun Leung* * Correspondence: waimun@ied. Abstract edu.hk Department of Chinese, The Hong After the handover of Hong Kong to China, a first-ever policy of “bi-literacy and Kong Institute of Education, Hong tri-lingualism” was put forward by the Special Administrative Region Government. Kong Under the trilingual policy, Cantonese, the most dominant local language, equally shares the official status with Putonghua and English only in name but not in spirit, as neither the promotion nor the funding approaches on Cantonese match its legal status. This paper reviews the status of Cantonese in Hong Kong under this policy with respect to the levels of government, education and curriculum, considers the consequences of neglecting Cantonese in the school curriculum, and discusses the importance of large-scale surveys for language policymaking. Keywords: the status of Cantonese, “bi-literacy and tri-lingualism” policy, language survey, Cantonese language education Background The adjustment of the language policy is a common phenomenon in post-colonial societies. It always results in raising the status of the regional vernacular, but the lan- guage of the ex-colonist still maintains a very strong influence on certain domains. Taking Singapore as an example, English became the dominant language in the work- place and families, and the local dialects were suppressed. It led to the degrading of both English and Chinese proficiency levels according to scholars’ evaluation (Goh 2009a, b). -

Children's Consonant Acquisition in 27 Languages

AJSLP Review Article Children’s Consonant Acquisition in 27 Languages: A Cross-Linguistic Review Sharynne McLeoda and Kathryn Crowea Purpose: Theaimofthisstudywastoprovideacross- most of the world’s consonants were acquired by 5;0 years; linguistic review of acquisition of consonant phonemes to months old. By 5;0, children produced at least 93% of inform speech-language pathologists’ expectations of children’s consonants correctly. Plosives, nasals, and nonpulmonic developmental capacity by (a) identifying characteristics consonants (e.g., clicks) were acquired earlier than trills, of studies of consonant acquisition, (b) describing general flaps, fricatives, and affricates. Most labial, pharyngeal, and principles of consonant acquisition, and (c) providing case posterior lingual consonants were acquired earlier than studies for English, Japanese, Korean, and Spanish. consonants with anterior tongue placement. However, Method: A cross-linguistic review was undertaken of there was an interaction between place and manner where 60 articles describing 64 studies of consonant acquisition by plosives and nasals produced with anterior tongue placement 26,007 children from 31 countries in 27 languages: Afrikaans, were acquired earlier than anterior trills, fricatives, and Arabic, Cantonese, Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, affricates. Greek, Haitian Creole, Hebrew, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Conclusions: Children across the world acquire consonants Jamaican Creole, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Maltese, Mandarin at a young age. Five-year-old children have acquired (Putonghua), Portuguese, Setswana (Tswana), Slovenian, most consonants within their ambient language; however, Spanish, Swahili, Turkish, and Xhosa. individual variability should be considered. Results: Most studies were cross-sectional and examined Supplemental Material: https://doi.org/10.23641/asha. single word production. Combining data from 27 languages, 6972857 hildren’s acquisition of speech involves mastery and the longer bars indicated greater variability (e.g., /t, s/). -

Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: Morphology and Syntax*

Breaking Down the Barriers, 785-816 2013-1-050-037-000234-1 Pan-Sinitic Object Marking: * Morphology and Syntax Hilary Chappell (曹茜蕾) EHESS In Chinese languages, when a direct object occurs in a non-canonical position preceding the main verb, this SOV structure can be morphologically marked by a preposition whose source comes largely from verbs or deverbal prepositions. For example, markers such as kā 共 in Southern Min are ultimately derived from the verb ‘to accompany’, pau11 幫 in many Huizhou and Wu dialects is derived from the verb ‘to help’ and bǎ 把 from the verb ‘to hold’ in standard Mandarin and the Jin dialects. In general, these markers are used to highlight an explicit change of state affecting a referential object, located in this preverbal position. This analysis sets out to address the issue of diversity in such object-marking constructions in order to examine the question of whether areal patterns exist within Sinitic languages on the basis of the main lexical fields of the object markers, if not the construction types. The possibility of establishing four major linguistic zones in China is thus explored with respect to grammaticalization pathways. Key words: typology, grammaticalization, object marking, disposal constructions, linguistic zones 1. Background to the issue In the case of transitive verbs, it is uncontroversial to state that a common word order in Sinitic languages is for direct objects to follow the main verb without any overt morphological marking: * This is a “cross-straits” paper as earlier versions were presented in turn at both the Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica, during the joint 14th Annual Conference of the International Association of Chinese Linguistics and 10th International Symposium on Chinese Languages and Linguistics, held in Taipei in May 25-29, 2006 and also at an invited seminar at the Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing on 23rd October 2006. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

Study on the Golf Professional Education Curriculum System in Colleges and Universities in China*

International Conference on Educational Research and Sports Education (ERSE 2013) Study on the Golf Professional Education Curriculum System in Colleges and Universities in China* Xueyun Shao Golf College Shenzhen University, Guangdong Province, China [email protected] Abstract - This paper, beginning with the status quo of meet the demand of high quality professional talent by the golf professional education in colleges and universities in our rapid development of golf sports in China, the author puts country. Three representatives colleges and universities of golf forward the proposal that the present golf professional professional education curriculum system are selected, i.e., education course system should be overall optimized based on Golf College of Shenzhen University (GC-SZU), Shenzhen principles systematicness and adaptability, feasibility and Tourism Institute of Jinan University (STI-JNU) and Tourism individualization and prominent golf professional Institute of Guangzhou University (TI-GZU). Those research characteristics and so on. At the same time, it has positive results of this paper have a positive practical significance on practical significance on improving the level of golf courses in improving the level of golf courses in colleges and universities colleges and universities in our country and also promoting the in our country, as well as promoting the development of development of China's golf industry. China's golf industry. II. Objects and Methods Index Terms - golf professional education, curriculum system, colleges and universities, China A. Objects I. Introduction In this paper, we take golf professional education curriculum system in Colleges and universities in China as the Within 20 years of time, the golf higher education in our research object. -

Download Our Latest Allegravita Backgrounder Booklet Here (PDF)

Name: Allegravita is an award-winning, multi- disciplinary public relations and strategic communications agency focused on supporting international clients in the China region and taking Chinese clients to the world. We were voted China's most entrepreneurial company by the Australian Chambers of ABOUT ALLEGRAVITA Commerce in China in 2008. Allegravita is a boutique global agency A PORTFOLIO OF SERVICES TO BORN IN CHINA, with personnel and offices in Beijing, HELP YOU SUCCEED IN CHINA EFFECTIVE WORLDWIDE Guangzhou, Kunming, Hong Kong, Public Relations for proactive and Although our focus is on the China New York City and San Francisco. Since reactive messaging. region, our services are very effective 2003 we have provided high-quality Marketing and Communications in markets worldwide, with proven PR, marketing and corporate advisory Collateral to present your messages outcomes. Allegravita works within services with a special focus on achiev- with excellent credibility. a highly-accountable and disciplined ing excellent results for international Media Relations & Media Training Western management style, executing clients in the China region and in Chi- to insert your messages into Chinese the highest quality of work for our nese speaking markets worldwide, and and international media in the most clients, which we deliver with agility, international results for our Chinese compelling way possible. flexibility, creativity and cultural savvy. clients. Corporate Identity localization to Allegravita is an ethnically diverse, We incorporate expert public relations communicate your brand values and multi-cultural team of professionals abilities with a firm grasp of contempo- benefits to Chinese markets, and for of different cultural heritages. What rary China-region marketplaces to help Chinese clients, to international inves- we share in common is our passion for our clients communicate effectively, tors and influencers. -

Development Strategy and Its Relevance to Higher

Policy Review ECNU Review of Education 2021, Vol. 4(1) 210–221 The Greater Bay Area (GBA) ª The Author(s) 2020 Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions Development Strategy and Its DOI: 10.1177/2096531120964466 Relevance to Higher Education journals.sagepub.com/home/roe Ailei Xie (谢爱磊) Guangzhou University Gerard A. Postiglione The University of Hong Kong Qian Huang (黄倩) The University of Hong Kong Abstract Purpose: This article provides a policy review of the Greater Bay Area (GBA) development strategies and their relevance to higher education. Design/Approach/Methods: This article reviews key GBA policies adopted by the central government of China and interprets higher education cooperation policies at provincial and national levels before discussing the opportunities and challenges for higher education. Findings: The GBA Development Strategy aims to build an integrated, innovative, and inter- nationalized economy. It presents an opportunity for universities to attract new funding opportunities as well as to prepare graduates to play a key role in the GBA. The shift toward a high-tech service-led economy would hinge upon creating an effective partnerships platform between industry and higher education institutions. To do so would require greater institutional and professional autonomy for the academic research enterprises. There is also a need for evidence-based policies by the Central and GBA regional governments. Corresponding author: Xie Ailei, School of Education, Guangzhou University, Rm 415, Wenqing Building, Guangzhou 510006, China. Email: [email protected] Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage). -

A Preliminary Analysis of Chinese-Foreign Higher Education Partnerships in Guangdong, China∗

US-China Education Review B, March 2019, Vol. 9, No. 3, 79-89 doi: 10.17265/2161-6248/2019.03.001 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Stay Local, Go Global: A Preliminary Analysis of Chinese-Foreign Higher Education Partnerships in Guangdong, China∗ Wong Wei Chin, Yuan Wan, Wang Xun United International College (UIC), Zhuhai, China Yan Siqi London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), London, England As China moves toward a market system after the “reforms and opening-up” policy since the late 1970s, internationalization is receiving widespread attention at many academic institutions in mainland China. Today, there are 70 Sino-Foreign joint institutions (namely, “Chinese-Foreign Higher Education Partnership”) presently operating within the Chinese nation. Despite the fact that the majority of these joint institutions have been developed since the 1990s, surprisingly little work has been published that addresses its physical distribution in China, and the prospects and challenges faced by the faculty and institutions on an operational level. What are the incentives of adopting both Western and Chinese elements in higher education? How do we ensure the higher education models developed in the West can also work well in mainland China? In order to answer the aforementioned questions, the purpose of this paper is therefore threefold: (a) to navigate the current development of internationalization in China; (b) to compare conventional Chinese curriculum with the “hybrid” Chinese-Foreign education model in present Guangdong province, China; and -

Cifu: a Frequency Lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 3069–3077 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Cifu: a frequency lexicon of Hong Kong Cantonese Regine Lai, Grégoire Winterstein The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Université du Québec à Montréal Department of Linguistics and Modern Languages, Département de Linguistique [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This paper introduces Cifu, a lexical database for Hong Kong Cantonese (HKC) that offers phonological and orthographic information, frequency measures, and lexical neighborhood information for lexical items in HKC. The resource can be used for NLP applications and the design and analysis of psycholinguistic experiments on HKC. We elaborate on the characteristics and challenges specific to HKC that were relevant in the design of Cifu. This includes lexical, orthographic and phonological aspects of HKC, word segmentation issues, the place of HKC in written media, and the availability of data. We discuss the measure of Neighborhood Density (ND), highlighting how the analytic nature of Cantonese and its writing system affect that measure. We justify using six different variations of ND, based on the possibility of inserting or deleting phonemes when searching for neighbors and on the choice of data for retrieving frequencies. Statistics about the four genres (written, adult spoken, children spoken and child-directed) within the dataset are discussed. We find that the lexical diversity of the child-directed speech genre is particularly low, compared to a size-matched written corpus. The correlations of word frequencies of different genres are all high, but in general decrease as word length increases. -

Stem Consonant Cooccurrence Restrictions in Ngbaka

Stem Consonant Cooccurrence Restrictions in Ngbaka Jeroen van de Weijer 1. Introduction Ngbaka is one of the languages spoken in the Central African Republic.1 It is part of the Adamawa Ubanguian branch of the Niger-Congo language family. The root cooccurrence restrictions in this language have attracted considerable attention since they were first reported by Thomas (1963) (see Wescott 1965; Chomsky and Halle 1968: 387; Clements 1982; Itô 1984; Churma 1984; Herbert 1986: 113-16; Mester 1986: 32-45; Sagey 1986: 260-66; Mester 1988; Lombardi 1990: 376 (fn. 2), among others). In Ngbaka there are vowel cooccurrence restrictions (not discussed here) and restrictions on the occurrence of consonants with the same point of articulation. The latter are stated below (from Wescott 1965, who summarises Thomas 1963: 63ff.): (1) (...) if a disyllabic word contains a voiceless consonant, it does not also contain the voiced counterpart of that consonant (that is, /p/ excludes /b/, /s/ excludes /z/, etc.). Similarly, if a disyllabic word contains a voiced obstruent, it does not also contain the prenasalized counterpart of that obstruent (that is, /b/ excludes /mb/, /z/ excludes /nz/, etc.); if such a word contains a prenasalized obstruent, it does not also contain the corresponding nasal (that is, /mb/ excludes /m/, /nz/ excludes /n/, etc.). (Wescott 1965: 346) The consonant inventory of Ngbaka is given below (see Thomas 1963: 55): Thanks to Colin Ewen, Harry van der Hulst, Grazyna Rowicka and an anonymous reviewer for useful discussion. All errors are my own. Linguistics in the Netherlands 1994, 259–266. DOI 10.1075/avt.11.25wei ISSN 0929–7332 / E-ISSN 1569–9919 © Algemene Vereniging voor Taalwetenschap 260 JEROEN VAN DE WEIJER (2) vcl obs p f t s k kp vcd obs b v d z g gb glottalised 'b prenasal mb nd nz ng ngb nasal m n p glide j w liquid 1 glottal stop ? glottal fricative h Ngbaka has seven oral and three nasal vowels (/ieeaoouâê ô/) and three tones (high, low, and mid - the latter of which is not marked in this paper). -

Biliterate and Trilingual: Actions in Response to the Economic Restructuring of Hong Kong

Published in Bulletin VALS-ASLA (Swiss association of applied linguistics) 82, 167-179, 2005 which should be used for any reference to this work Biliterate and Trilingual: Actions in response to the economic restructuring of Hong Kong Yinbing LEUNG Dept. of Education Studies, Hong Kong Baptist University, 33 Renfrew Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong; [email protected] Depuis le transfert de souveraineté de la Grande-Bretagne à la Chine en 1997, les structures politiques, sociales et économiques de Hong Kong ont subi de rapides changements, entraînant un réalignement linguistique au sein de la société. Le putonghua (la langue nationale de Chine) occupe une place de plus en plus importante, en partie à cause des liens politiques avec la Chine, mais surtout à cause de la dépendance grandissante économique de Hong Kong vis-à-vis d'elle. Le dialecte local, le cantonais, est la langue maternelle d'environ 90% de la population. En vue de ce contexte linguistique, le gouvernement s'est engagé à poursuivre une politique linguistique de "double alphabétisation et de trilinguisme". Dans le dernier rapport sur l'enseignement linguistique (SCOLAR 2003), plusieurs propositions sont faites afin de promouvoir la compétence des étudiants et de la population active en anglais et en putonghua. Le dialecte local fait l'objet de peu d'attention. Dans cet article, je soutiens que ces diverses propositions favorisent l'anglais et le putonghua afin d'assurer la compétitivité de Hong Kong dans l'économie mondiale. Le succès de la promotion du putonghua n'est pas lié aux questions d'identité nationale mais dû à une combinaison d'affinités culturelles et de ration- alité économique. -

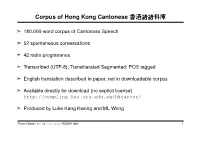

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港港港語語語語語語料料料庫庫庫

Corpus of Hong Kong Cantonese 香香香港nn;;;;;;$$$庫庫庫 ã 180,000-word corpus of Cantonese Speech ã 52 spontaneous conversations ã 42 radio programmes ã Transcribed (UTF-8); Transliterated Segmented; POS tagged ã English translation described in paper, not in downloadable corpus ã Available directly for download (no explicit license) http://compling.hss.ntu.edu.sg/hkcancor/ ã Produced by Luke Kang Kwong and ML Wong Francis Bond <[email protected]> HG3051 lab2 1 Creation ã 30 hours of recordings (March 1997 — August 1998) ã Native speakers of Cantonese ã ordinary settings with family members, friends and colleagues talking with each other freely on everyday topics such as current affairs, work and study, and personal hobbies ã Some parts selected 2 Meta-Data/Annotation ã Meta-Data Tape number (of recording); Date of recording Number of Speakers; List of Speakers (Code-Sex-Age-Origin) (e.g. A-M-22-HK says A is a 22-year-old male speaker from Hong Kong) ã Annotation Each Utterance has the speaker code Utterances are segmented, POS tagged and transliterated Ç%h/d/ge3i1bun2soeng6/ 2個/r/ni1go3/ze ... ã The whole corpus is wrapped in xml (but not very well) 3 Usage ã Used to examine the uses of the frequently used sentence final particles woˇ and boˇ in the 1990s in Hong Kong Cantonese by examining speech data. ã Question: are woˇ (喎) and boˇ (S) variant forms? ã Answer: No “[. ] the two SFPs carry and serve different meanings and functions in modern Hong Kong Cantonese, and thus they are not exactly the same particles and not interchangeable as previously assumed.” (Leung, 2010, p21) ã Also used as a corpus in the PyCantonese Project: Working with Cantonese corpus data using Python, by Jackson L.