Thai Cuisine Regional Cuisines and Historical Influences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese / Thai Entrees Soups Noodle Or Rice Bowls Stir-Fried

chinese / thai entrees soups Lunch Specials are served with Choice of Soup (Miso, Hot & Sour or Egg Drop) and Choice of Rice (White Rice or Vegetable Fried Rice) (Dine-In Only) Egg Drop Soup 蛋花湯 2.15 Lunch Dinner Fried Tofu or Vegetable 9.95 12.95 Hot and Sour Soup 酸辣湯 2.45 Chicken 10.50 14.95 Miso Soup 味噌湯 2.15 Beef or Medium-Size Shrimp 10.95 15.95 Combo (Medium-Size Shrimp, Beef, Chicken) 10.95 15.95 Japanese soybean paste (“miso”) soup Dinner Combo (Jumbo Shrimp, Beef, Chicken) 15.95 Creamy Chicken Corn Soup (For 2) 雞茸玉米湯 6.55 Jumbo Shrimp or Seafood 15.95 Vegetable and Tofu Soup (For 2) 蔬菜豆腐湯豆腐湯 6.55 Garlic Sauce 魚香汁 Stir-fried with chili peppers and garlic (vegetarian option Seafood and Tofu Soup (For 2)海鮮豆腐湯豆腐羹 8.75 is with eggplant) Chicken with Shitake Soup (For 2) 冬菇雞片湯 7.65 Hunan Style 湖南汁 Quick-fired with special hot & spicy sauce with mixed Minced Beef with Egg White Soup (for 2)西湖牛肉羹 8.75 vegetables Black Bean Sauce 豉椒汁 noodle or rice bowls Onions, red and green peppers in a spicy black bean sauce Stir-Fried Entrees with Savory Sauce Served over Cashew Nuts 腰果 Lo Mein Noodles or Rice (Brown Rice Add $1.25) Made with cashew nuts, peppers, zucchini and scallions Vegetable or Chicken $10.95 / Beef, Shrimp, or Combo (add $1.25) Chinese Mixed Vegetables 什錦蔬菜 Jumbo Shrimp (add $2.50) Quick-fired with a flavorful sauce General Tso’s (Chicken or Shrimp)左公雞(蝦)蓋飯/麵 Chinese Stir-Fried Broccoli 西芥蘭 Curry Sauce 咖哩蓋飯/麵 Sautéed with a light brown sauce Garlic Sauce 魚香蓋飯/麵 Kung Pao 宮保 Peanuts, chili peppers, zucchini, and scallions -

Dishes May Not Come out Exactly As Shown

= Favorites = Gluten Free V = Vegetarian = Contains Dairy = Spicy - served medium spicy unless otherwise requested *Images intended for reference only; dishes may not come out exactly as shown. *Please let your server know if you have any food allergies or dietary restrictions. * Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. Flat Rice Noodles Egg Wheat Noodles noodle types Vermicelli Rice Noodles Flat Egg Wheat Noodles Chow Fun Rice Noodles Lo Mein Wheat Noodles Round Rice Noodles Udon Noodles A1. Fried Eggrolls (Chả Giò) | 5.95 minced filling rolled in a crispy wrapper and deep fried until golden brown (4pc per order) shrimp and pork – served with fish sauce vegetable – served with sweet and sour sauce vegan net eggrolls – served with fish sauce A2. Fried Crab Rangoon (Hoành Thánh Chiên) | 5.95 appetizers creamy crab and veggie dumplings deep fried in a crispy golden wonton wrapper (8pcs per order) A3. Summer Rolls (Gỏi Cuốn) | 4.95 fresh rice paper rolls served cold with noodles, lettuce, mint, and a side of our delicious peanut sauce (2pcs per order) add avocado for 1.00 shrimp (tôm) grilled pork patties (nem nướng) shrimp and pork patty combo (tôm & nem nướng) A4. Dumplings (Sủi Cảo) | 5.95 savory steamed or fried dumplings with your choice of veggie or meat filling and a side of our tangy homemade dumpling sauce (8pcs per order) A5. Chicken Wings (Cánh Gà) | 6.95 seasoned grilled or fried chicken wings with a side of house spicy mayo (6pcs per order) A6. Crispy Squid (Mực Chiên Dòn) | 6.95 beautiful golden rings of squid deep fried in a crispy panko batter and served with a side of our homemade sweet and sour or spicy mayo (10 pcs per order) A7. -

Starters Soups Noodle Soups Pan Fried

We are not a fast food restaurant. Your dish is made fresh when ordered. PLEASE BE PATIENT. STARTERS FRIED CRAB WONTONS 6pcs $4 FIRECRACKER SHRIMP - marinated shrimp (mild) rolled inside egg roll wrappers & fried - served with sweet chili sauce FRIED PORK WONTONS 6pcs $4 6pcs $7.50 FRIED CABBAGE ROLLS - shredded cabbage and clear noodles BANH CUON - steamed rice rolls filled with ground pork and rolled into an egg roll, deep fried & served with our homemade wood ear mushrooms, topped with thinly sliced pork sausage and sweet & sour sauce 2pcs $4 fried garlic - served with a mild vinegar fish sauce (GF) 5pcs $7.50 FRIED EGG ROLLS - ground pork, shredded cabbage, carrots FRIED CHICKEN WINGS - 3 whole wings (separated) $7.50 and bean thread noodles. served with a mild vinegar fish sauce 2pcs $4 LAO SAUSAGE (SAI OUA) - minced pork belly blended with lemongrass, kaffir leaves, shallots, peppers, and other seasonings FRESH SPRING ROLLS (NOT FRIED) - Fresh lettuce, carrots, - served with our spicy roasted tomato dip (mild spice) 3 links $8 cilantro, cucumber, vermicelli noodles & your choice of protein rolled inside of rice wrappers - served with your choice of dipping FRIED RIBS - marinated pork ribs - served with our spicy roasted sauce: peanut sauce, sweet chili, or vinegar fish sauce tomato dip 7pcs $7.50 + beef, chicken, pork, tofu or vegetables 2pcs $4 STEAMED RICE $1 + shrimp 2pcs $5 STICKY RICE $3 CHICKEN SATAY - chicken strips pan fried with coconut cream, served with peanut sauce & pickled vegetables (GF) 5pcs $7.50 SOUPS HOT & SOUR - a -

Appetizers & Sandwiches Noodle Soups Vietnamese

APPETIZERS & SANDWICHES ASIAN SPECIALTIES SERVED 5PM - CLOSING 1 Chả Giò 12.95 16 Singapore Noodles 21.95 Authentic Vietnamese fried pork & Rice vermicelli noodles stir-fried to perfection, served with shrimp egg rolls. Chinese bbq pork, eggs, shrimp, green onions, celery and curry powder. 2 Gỏi Cuốn / Gỏi Cuốn Chay 12.95 Fresh pork & shrimp or vegetarian spring rolls, 17 Mongolian Beef 25.95 served with authentic Vietnamese peanut sauce. This American-Chinese fusion dish is sure to delight, 3 Bánh Mì 14.95 consisting of sautéed tender sliced beef, Choice of bbq pork or chicken, served with green onions, fresh tomatoes and bell peppers homemade mayonnaise, cilantro, jalapeños, cucumber, finished in a savory sauce, served with pickled carrots & daikon, on a French roll. steamed rice and crispy fried noodles. 4 Spicy Edamame 9.95 18 Szechuan-Style Lo Mein Beef 24.95 Shrimp 26.95 Lo mein noodles with choice of shrimp or beef in our homemade spicy szechuan sauce. NOODLE SOUPS 19 Chow Fun Noodles 5 Phở Tái*/** 19.95 Beef 24.95 Shrimp 26.95 Rare beef with rice noodle soup. Cantonese-style stir-fried wide rice noodles, served with choice of beef or shrimp. 6 Phở Chín** 19.95 Rice noodle soup served with tender 20 Sweet & Sour cooked beef brisket. Chicken 22.95 Shrimp 26.95 Stir-fried with pineapple chunks, red & green bell peppers, 7 Phở Bò Viên With Chả Lụa 20.95 yellow onions, tossed in our homemade sweet & sour sauce, Choice of pho noodles or vermicelli, served with served with steamed rice. -

THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK

ROUGH GUIDES THE ROUGH GUIDE to Bangkok BANGKOK N I H T O DUSIT AY EXP Y THANON L RE O SSWA H PHR 5 A H A PINKL P Y N A PRESSW O O N A EX H T Thonburi Democracy Station Monument 2 THAN BANGLAMPHU ON PHE 1 TC BAMRUNG MU HABURI C ANG h AI H 4 a T o HANO CHAROEN KRUNG N RA (N Hualamphong MA I EW RAYAT P R YA OAD) Station T h PAHURAT OW HANON A PL r RA OENCHI THA a T T SU 3 SIAM NON NON PH KH y a SQUARE U CHINATOWN C M HA H VIT R T i v A E e R r X O P E N R 6 K E R U S N S G THAN DOWNTOWN W A ( ON RAMABANGKOK IV N Y E W M R LO O N SI A ANO D TH ) 0 1 km TAKSIN BRI DGE 1 Ratanakosin 3 Chinatown and Pahurat 5 Dusit 2 Banglamphu and the 4 Thonburi 6 Downtown Bangkok Democracy Monument area About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The colour section is designed to give you a feel for Bangkok, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The city chapters cover each area of Bangkok in depth, giving comprehensive accounts of all the attractions plus excursions further afield, while the listings section gives you the lowdown on accommodation, eating, shopping and more. -

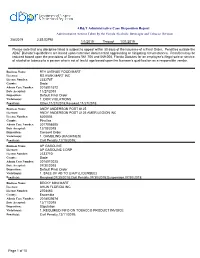

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report by Date

AB&T Administrative Case Disposition Report Administrative Actions Taken by the Florida Alcoholic Beverages and Tobacco Division 2/8/2019 2:35:52PM 1/1/2019 Through 1/31/2019 Please note that any discipline listed is subject to appeal within 30 days of the issuance of a Final Order. Penalties outside the AB&T Division's guildelines are based upon extensive documented aggravating or mitigating circumstances. Penalties may be reduced based upon the provisions of Sections 561.706 and 569.008, Florida Statutes for an employee's illegal sale or service of alcohol or tobacco to a person who is not of lawful age based upon the licensee's qualification as a responsible vendor. Business Name: 9TH AVENUE FOOD MART Licensee: RS KWIK MART INC License Number: 2332787 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018011572 Date Accepted: 11/27/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. DOR VIOLATIONS Penalty(s): Other,11/27/2018;Revoked,11/27/2018; Business Name: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 Licensee: ANDY ANDERSON POST #125 AMER LEGION INC License Number: 6200504 County: Pinellas Admin Case Number: 2017056505 Date Accepted: 12/18/2018 Disposition: Consent Order Violation(s): 1. GAMBLING (MACHINES) Penalty(s): Civil Penalty,12/18/2018; Business Name: AP GASOLINE Licensee: AP GASOLINE CORP License Number: 2333710 County: Dade Admin Case Number: 2018012025 Date Accepted: 07/30/2018 Disposition: Default Final Order Violation(s): 1. SALE OF AB TO U/A/P (LICENSEE) Penalty(s): Revoked,07/30/2018;Civil Penalty,07/30/2018;Suspension,07/30/2018; Business Name: BECKY MINI MART Licensee: AHUN FLORIDA INC License Number: 2704463 County: Escambia Admin Case Number: 2018039574 Date Accepted: 12/11/2018 Disposition: Stipulation Violation(s): 1. -

Restaurant Oriental Wa-Lok

RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK DIRECCIÓN:JR.PARURO N.864-LIMA TÉLEFONO: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK BOCADITOS APPETIZER 1. JA KAO S/.21.00 Shrimp dumpling 2. CHI CHON FAN CON CARNE S/.17.00 Rice noodle roll with beef 3. CHIN CHON FAN CON LAN GOSTINO S/.20.00 Rice noodle roll with shrimp 4. CHIN CHON FAN SOLO S/.14.00 Rice noodle roll 5. CHIN CHON FAN CON VERDURAS S/.17.00 Rice noodle with vegetables 6. SAM SEN KAO S/.25.00 Pork, mushrooms and green pea dumplings 7. BOLA DE CARNE S/.19.00 Steam meat in shape of ball 8. SIU MAI DE CARNE S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with beef 9. SIU MAI DE CHANCHO Y LANGOSTINO S/.18.00 Siumai dumpling with pork and shrimp 10. COSTILLA CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Steam short ribs with black beans sauce 11. PATITA DE POLLO CON TAUSI S/.17.00 Chicken feet with black beans 12. ENROLIADO DE PRIMAVERA S/.17.00 Spring rolls 13. ENROLLADO 100 FLORES S/.40.00 100 flowers rolls 14. WANTAN FRITO S/.18.00 Fried wonton 15. SUI KAO FRITO S/.20.00 Fried suikao 16. JAKAO FRITO S/.21.00 Fried shrimp dumpling Dirección: Jr. Paruro N.864-LIMA Tel: (01) 4270727 RESTAURANT ORIENTAL WA-LOK 17. MIN PAO ESPECIAL S/.13.00 Steamed special bun (baozi) 18. MIN PAO DE CHANCHO S/.11.00 Steamed pork bun (baozi) 19. MIN PAO DE POLLO S/.11.00 Steamed chicken bun (baozi) 20. MIN PAO DULCE S/.10.00 Sweet bun (baozi) 21. -

Cuisines of Thailand, Korea and China

Journal of multidisciplinary academic tourism ISSN: 2645-9078 2019, 4 (2): 109 - 121 OLD ISSN: 2548-0847 www.jomat.org A General Overview on the Far East Cuisine: Cuisines of Thailand, Korea and China ** Sevgi Balıkçıoğlu Dedeoğlu*, Şule Aydın, Gökhan Onat ABSTRACT Keywords: Far east cuisine Thailand The aim of this study is to examine the Thai, Korean and Chinese cuisines of the Far East. Far Eastern Korea cuisine has a rich culinary culture that has hosted many civilizations that serve as a bridge between past China and present. Thai, Korean and Chinese cuisines are the most remarkable ones among the Far Eastern Ethnic Food cuisines. Therefore, these three cuisines have been the main focus of this study. In this study, cuisines’ history and their development are explained by giving basic information about these three countries. After this step, the general characteristics of the cuisines of these countries are mentioned. Finally, some of the foods that are prominent in these countries and identified with these countries are explained in Article History: general terms. Submitted: 04.06.2019 Accepted:07.12.2019 Doi: https://doi.org/10.31822/jomat.642619 1. Introduction With the reflection of postmodern consumption East can be highlighted in order to be able to mentality on tourist behavior, national cuisines attract them to these regions. As a matter of fact, have reached another level of importance as tourist the popularity of many cuisines from the Far East attractions. Despite the fact that local food has an regions is gradually increasing and they are important place in the past as a touristic product, becoming an attraction element. -

Kûng Phrik H̄wān Kratium

Kûng Phrik H̄ wān Kratium Thai Sweet Chile Garlic Shrimp Yield: Serves 4-6 Ingredients: 1 lb Jumbo Shrimp [21-25] (Kûng) - shelled and deveined; tail on 4 cloves Fresh Garlic (Kratiam) - minced ¼ Cup Thai Sweet Chile Sauce (Sxs̄ Phrik H̄ wān / Nam Jim Kai) 1 Tbs Chile Garlic Sauce (Nam Phrik Pao) 2 tsp Palm Sugar (Nam Tan Puek) - grated fine 1 Tbs Thai Thin/Light Soy Sauce (Si-io Kaow) Juice of 1 Lime (Naam Manao) Ground White Pepper (Phrik Thai Bpon) to taste 3 Tbs Peanut Oil (Dtohn Thuaa li Sohng) – divided -OPTIONAL GARNISH- Fresh Coriander Leaves (Phak Chi) - small chopped Fresh Thai Basil Leaves (Horapha) - small chopped Green Onion (Hom) - thin sliced Lime wedges (Manao) Preparation: 1) Lightly season the shrimp with the white pepper to taste 2) Heat 1 ½ Tbs (half) of the peanut oil in a medium/large wok or skillet over medium-high heat until shimmering - Once the oil is hot, add the shrimp and fry until slightly browned (apx 1 minute) - Flip and repeat 3) Transfer the seared shrimp to a clean plate and set aside until needed 4) Return the wok/skillet to the heat and add the reaming 1 ½ Tbs of the peanut oil and allow to heat for 30 seconds or so 5) Add the garlic and sauté until just golden (apx 45 seconds) - Add back the shrimp and give it a toss 6) Add the sweet chile sauce, chile garlic sauce, palm sugar, soy sauce, and lime juice - Sauté until sugar is completely dissolved and shrimp is well coated 7) Transfer to a serving dish, garnish as desired, and serve immediately with jasmine rice and/or green papaya salad (Som Tam) Taz Doolittle www.TazCooks.com . -

Mamweb: Regional Styles of Thai Cuisine

Regional Styles of Thai Cuisine: Thailand is comprised of four main culinary regions, each with their own specialties, and each having slight deviations in flavor profile from that of the Central region, which is considered by most to be the ‘classic’ Thai culinary style. The variations are caused by differences in ethnicity, cultural background, geography, climate, and to some extent, politics. Each ethnographic group can lay claim to dishes which are known nationwide, whether they originated with the Chinese immigrants from Hainan, Fujian, Guangzhou, or Yunnan, the Sunni Muslim Malays or animist Moken sea gypsies in the South, the Mon of the west-Central, the Burmese Shan in the North, the Khmer in the East, or the Lao in the Northeast. Geography and climate determine what can be grown and harvested, and whether the aquatic species consumed in the region are derived from the sea or freshwater. The cuisine of Northeastern Thailand: Aahaan Issan: Issan (also written as Isaan, Isarn, Esarn, Isan) is Thailand’s poorest region, both economically and agriculturally. It is plagued by thin soils, with an underlying layer of mineral salts (mineral salt is harvested and exported country wide). The weather is a limiting factor in agricultural production: it is hotter and dryer during the dry season, and rains can easily become floods, since it is basically a large flat plateau (the Khorat Plateau), hemmed-in by mountain ranges to the west and the south. Watersheds are limited and flow into the Mekong, which serves as a transportation link for trade. Marshes and temporary lakes appear during the rainy season. -

MYANMAR POCKET GUIDE Hotline

Hotline: +95 9976535660 Bagan hello@trailsofindochina.com www.trailsofindochina.com MYANMAR POCKET GUIDE TRAILS OF INDOCHINA BAGAN 2 A glimpse back in time to the ancient Burmese Kingdom Situated on the plains next to the Ayeyarwaddy River, this ancient city is dotted with thousands of age-old stupas and temples from different eras, making it one of the most remarkable archaeological sites in Asia. The breathtaking views of the brick temples, against the backdrop of expansive plains, are unforgettable Bagan was the first capital of the Burmese Empire, between the 11th and 13th centuries. During this time there were over 10,000 Buddhist temples, pagodas and monasteries that populated the expansive plains of the ancient kingdom. TRAILS OF INDOCHINA BAGAN 2 Places To Eat Must-Try Local Foods Dine like Burmese royalty in Bagan. Traditions from the ancient kingdom live on in the city’s cuisine. Try the flavours of the local food in an authentic Myanmar atmosphere. PARATHA Indian-style flatbread typically eaten with curries BURMESE SALADS A variety of different salads varying from tofu to, tea leaf, and tomato and cabbage STICKY RICE Sticky rice typically served with shredded coconut BURMESE THALI MOHINGA A round platter serving Rice noodle and fish various dishes including soup, typically eaten for chutneys, beans and curries breakfast TRAILS OF INDOCHINA BAGAN 4 MYANMAR INTERNATIONAL DINING DINING Pricing Reference: $ - Inexpensive $$ - Moderate $$$ - Expensive Sunset Garden $$ This appropriately named and charming restaurant boasts Eden B.B.B $$$ a landscaped garden, stunning views, a cool breeze and This beautifully furnished restaurant offers a choice of mouth-watering food. -

Hua Hin Beach

Cover_m14.indd 1 3/4/20 21:16 Hua Hin Beach 2-43_m14.indd 2 3/24/20 11:28 CONTENTS HUA HIN 8 City Attractions 9 Activities 15 How to Get There 16 Special Event 16 PRACHUAP KHIRI KHAN 18 City Attractions 19 Out-Of-City Attractions 19 Local Products 23 How to Get There 23 CHA-AM 24 Attractions 25 How to Get There 25 PHETCHABURI 28 City Attractions 29 Out-Of-City Attractions 32 Special Events 34 Local Products 35 How to Get There 35 RATCHABURI 36 City Attractions 37 Out-Of-City Attractions 37 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 2-43_m14.indd 3 3/24/20 11:28 HUA HIN & CHA-AM HUA HIN & CHA-AM Prachuap Khiri Khan Phetchaburi Ratchaburi 2-43_m14.indd 4 3/24/20 11:28 2-43_m14.indd 5 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 6 3/24/20 11:28 The Republic of the Union of Myanmar The Kingdom of Cambodia 2-43_m14.indd 7 3/24/20 11:28 Hat Hua Hin HUA HIN 2-43_m14.indd 8 3/24/20 11:28 Hua Hin is one of Thailand’s most popular sea- runs from a rocky headland which separates side resorts among overseas visitors as well as from a tiny shing pier, and gently curves for Thais. Hua Hin, is located 281 kiometres south some three kilometres to the south where the of Bangkok or around three-hour for driving a Giant Standing Buddha Sculpture is located at car to go there.