Angola: Nationalist Narratives and Alternative Histories Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century John Whitney Harvey Dissertação em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos Orientador: Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim Setembro, 2012 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim e a coorientação científica do Professor Doutor Diogo Ramada Curto. I dedicate this dissertation to my father, Charles A. Harvey Jr. (1949-2009), whose wisdom, hard work, and dedication I strive to emulate. The last thing he knew about me was that I was going to study at FCSH, and I hope that I have made him proud. Acknowledgements There are so many people that were instrumental to the production of this dissertation that it would be impossible to include everyone in this space. I want to take the opportunity to thank everyone that supported me emotionally and academically throughout this year. Know that I know who you are, I appreciate everything done for me, and hope to return the support in the future. I would also like to thank the Center for Overseas History for the resources and opportunities afforded to me, as well as all of my professors and classmates that truly enriched my academic career throughout the last two years. There are some people whom without, this would not have been possible. The kindness, friendship, and support shown by Nuno and Luisa throughout this process I will never forget, and I am incredibly grateful and indebted to you both. -

Introduction

Introduction The cover image of a wire-and-bead-art radio embodies some of this book’s key themes. I purchased this radio on tourist-thronged Seventh Street in the Melville neighborhood of Johannesburg. The artist, Jonah, was an im- migrant who fled the authoritarianism and economic collapse in his home country of Zimbabwe. The technology is stripped down and simple. It is also a piece of art and, as such, a representation of radio. The wire, beadwork, and swath of a Coca-Cola can announce radio’s energy, commercialization, and global circulation in an African frame. The radio works, mechanically and aesthetically. The wire radio is whimsical. It points at itself and outward. No part of the radio is from or about Angola. But this little radio contains a regional history of decolonization, national liberation movements, people crossing borders, and white settler colonies that turned the Cold War hot in southern Africa. Powerful Frequencies focuses on radio in Angola from the first quarter of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first century. Like a radio tower or a wire-and-bead radio made in South Africa by a Zimbabwean im- migrant and then carried across the Atlantic to sit on a shelf in Bloomington, Indiana, this history exceeds those borders of space and time. While state broadcasters have national ambitions—having to do with creating a com- mon language, politics, identity, and enemy—the analysis of radio in this book alerts us to the sub- and supranational interests and communities that are almost always at play in radio broadcasting and listening. -

A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade? Boxell, Levi Stanford University 3 March 2016 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/69853/ MPRA Paper No. 69853, posted 06 Mar 2016 12:59 UTC A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?∗ Levi Boxell† Stanford University First Version: June 6, 2015 This Version: March 4, 2016 Abstract Historians have frequently suggested that droughts helped facilitate the African slave trade. By introducing a previously unused dataset on historical rainfall levels in Africa, I provide the first empirical answer to this hypothesis. I demonstrate how negative rainfall shocks and long-run shifts in the mean level of rainfall increased the number of slaves exported from a given region and can have persistent effects on the level of development today. Using a simple economic model of an individual’s decision to participate in the slave trade, along with observed empirical heterogeneity and historical anecdotes, I argue that consumption smoothing and labor allocation adjustments are the primary causal mechanisms for the negative relationship between droughts and slave exports. These findings contribute to our understanding of the process of selection into the African slave trade and have policy implications for contemporary human trafficking and slavery. JEL Classification: N37, N57, O15, Q54 Keywords: slave trade, climate, droughts, consumption smoothing, human trafficking ∗Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Jiwon Choi, John T. Dalton, James Fenske, Matthew Gentzkow, Namrata Kala, Andres Shahidinejad, Jesse M. Shapiro, and Michael Wong for their comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are mine. †SIEPR, Stanford University (Email: [email protected]) 1 1 Introduction The African slave trade significantly altered modern economic and cultural outcomes (Nunn, 2008). -

A Rebelião Interna No Mpla Em 1977 E As Confusões No Noticiário De Zero Hora E Correio Do Povo

QUEM SÃO OS REBELDES, AFINAL? A REBELIÃO INTERNA NO MPLA EM 1977 E AS CONFUSÕES NO NOTICIÁRIO DE ZERO HORA E CORREIO DO POVO. MAURO LUIZ BARBOSA MARQUES 1 O presente artigo buscar analisar as dicotomias e as abordagens contraditórias dos periódicos gaúchos Zero Hora e Correio do Povo 2 durante a crise interna do MPLA 3, partido governante em Angola no ano de 1977. Angola foi a principal possessão lusitana até 1975 – ano da ruptura colonial angolana -, quando a partir de um cenário marcado por violentas disputas internas e externas, parte do contexto internacional daquele período, houve caminhos e descaminhos na consolidação deste novo Estado Nacional pós colonização, especialmente entre os anos 1975 e 1979 quando Agostinho Neto 4 e o MPLA comandaram o primeiro governo independente contemporâneo de Angola. Um destes fatores de consolidação política de um novo Estado Nacional se deu na disputa da esfera superior de poder no interior do MPLA durante a condução do Estado Nacional, em maio de 1977. Algo tradicional, em especial na tradição africana contemporânea permeada com debilidades nas estruturas estatais e disputas palacianas. 1 Mestre em História pela UFRGS (Porto Alegre/RS) atua na rede pública estadual e municipal na cidade de São Leopoldo (RS). 2 Estes periódicos tinham grande circulação estadual e somados tinham uma tiragem superior a cem mil exemplares no período analisado por esta pesquisa, conforme informado na capa dos mesmos (nota do autor). 3 O médico e poeta Antonio Agostinho Neto formou o MPLA (Movimento Popular para Libertação de Angola), que tinha como referência o bloco socialista e contou com o apoio decisivo da URSS e dos cubanos na hora da ruptura com Portugal em novembro de 1975. -

As Memórias Do 27 De Maio De 1977 Em Angola

As memórias do 27 de maio de 1977 em Angola Inácio Luiz Guimarães Marques 27 de maio de 1977. Há 34 anos aconteceu em Angola um dos episódios mais polêmicos, controversos e violentos de sua história recente. 18 meses após a Independência, proclamada pelo MPLA em 11 de novembro de 1975, a crise nitista evidenciou o alcance das contradições internas no MPLA. A expressão nitista, ou nitismo, refere-se a um dos principais lideres da contestação, Alves Bernardo Baptista, Nito Alves, guerrilheiro da 1ª região Político-militar durante a guerra de libertação, que aparece com mais evidencia no Movimento durante o Congresso de Lusaka, em 1974, defendendo as posições do presidente Agostinho Neto. Como aliado chegou aos altos escalões do Movimento, o que lhe rendeu o cargo de Ministro da Administração Interna no primeiro governo independente, em 1975. Durante o ano de 1976, grosso modo, sua posição político-ideológica – a favor do estabelecimento de um governo marxista- leninista – foi progressivamente conquistando adeptos e, ao mesmo tempo, provocando atritos com o Governo, que ao contrário insistia em uma chamada Revolução democrática e popular que não ameaçasse sua legitimidade. Em outubro deste mesmo ano foi acusado, juntamente com seus principais aliados, José-Van-Dunem e Sita Vales, de traição, o que lhe custou a perda do cargo de Ministro. Apesar disso, não cedeu aos pedidos para que se calasse, o que rendeu a Nito Alves – e também a Van-Dunem – a expulsão formal em 20 de Maio de 1977 dos quadros do Movimento. Apenas uma semana depois, no dia 27, tentaria sem sucesso derrubar o Governo. -

Intimate Encounters with the State in Post-War Luanda, Angola

Intimate Encounters with the State in Post-War Luanda, Angola Chloé Buire Les Afriques dans le Monde, CNRS, Pessac, France Abstract: Since the end of the war in 2002, Luanda has become an iconic site of urban transformation in the context of a particularly entrenched oligarchic regime. In practice however, urban dwellers are often confronted with a ‘deregulated system’ that fails to advance a coherent developmental agenda. The paper narrates the trajectory of a family forcibly removed from the old city to the periphery. It shows how city- dwellers experience the control of the party-state through a series of encounters with authority across the city. Questioning the intentionality of a state that appears at the same time omnipotent and elusive, openly violent and subtly hegemonic, the paper reveals the fine mechanisms through which consent is fabricated in the intimacy of the family. In 2001, guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi is hiding in the hinterlands of Angola; but on the Atlantic coast, the shadows of the civil war are dissipating and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the ruling party of Angola since 1975, announces ambitious reconstruction works in the capital city Luanda. In an old bairro (neighbourhood) near the city centre, Avo Monteiro, once a cook at one of the best hotels in town, gets the notice that will change the life of his whole family: his house is to be demolished to give way to a new road. A few months later, Savimbi is killed; the peace treaty that unfolds allows the MPLA to extend its control to the entire country and consolidate its grasp on all levels of government. -

Cuba E União Soviética Em Angola: 1977

Cuba e União Soviética em Angola: 1977 Cristina Portella Doutoranda em História Social Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil) Luis Leiria Jornalista Portal Esquerda.net (Portugal) Resumo: No dia 27 de maio de 1977, em Angola, o governo de Agostinho Neto desencadeou um processo repressivo que ocasionou a morte de milhares de aderentes do MPLA. O objetivo, de acordo com a justificação oficial, seria impedir um golpe de Estado liderado pelo ex-ministro da Administração Interna Nito Alves. Nessa altura, estavam presentes em Angola tropas cubanas e oficiais da URSS. A historiografia oferece várias interpretações para este episódio, marcante na história do país recém-independente. Este artigo discute os fatos, as causas e as consequências do “27 de Maio”, à luz de documentos cubanos recentemente desclassificados, reunidos por Piero Gleijeses, professor de política externa norte-americana na School of Advanced International Studies da Universidade Johns Hopkins, no portal do Wilson Center Digital Archive International - History Declassified. Palavras-chave: 1. Angola, 2. MPLA, 3. Cuba, 4. União Soviética Abstract: On May 27, 1977, in Angola, the government of Agostinho Neto triggered a repressive process that led to the deaths of thousands of MPLA members. The goal, according to official justification, would be to prevent a coup led by former Home Minister Nito Alves. At that time, Cuban troops and USSR officers were present in Angola. Historiography offers several interpretations for this episode, striking in the history of the newly independent country. This article discusses the facts, causes, and consequences of “May 27,” in light of recently declassified Cuban documents, gathered by Piero Gleijeses, a professor of US foreign policy at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Wilson Center Digital Archive International Portal - History Declassified Keywords: 1. -

Uma Punhalada Na História Lara Pawson 163 Citação, Os Autores Levantam Suspeitas O Casal Mateus Diria Provavelmente Que Quanto À Veracidade Da Mesma

rece n s ão DALILA CABRITA MATEUS Uma punhalada e ÁLVARO MATEUS Purga em Angola – na história nito Alves, Sita Valles, Zé Van Lara Pawson Dunem, o 27 de Maio de 1977 Lisboa, Edições ASA, 2007, 208 páginas quilo que não foi publicado acerca do 27 de Maio A ao longo das três últimas décadas consegue ser tão intrigante quanto aquilo que o foi. A ausência de infor- mação pública sobre um dos mais significativos aconte- cimentos da história de Angola dos últimos cinquenta anos é frustrante, e exemplar da natureza autoritária do regime do Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA). Tão-só por esse motivo, estas cerca de 200 pági- nas, da autoria de Dalila e Álvaro Mateus, constituem um contributo valiosíssimo. O aspecto mais forte do texto resulta da circunstância, nova e necessária, de os autores se recusarem a aceitar uma vírgula sequer da versão oficial que o MPLA propala acerca dos aconteci- mentos, não obstante a ampla aceitação O primeiro capítulo apresenta-nos os qua- de que tal versão ainda goza, nomeada- tro homens que não se limitam a ser os mente entre estrangeiros – intelectuais, protagonistas desta obra; são verdadeira- jornalistas e observadores da realidade mente os heróis não celebrados do MPLA angolana. Ao invés, insistem em aprofun- e de Angola. Eduardo Artur Santana Valen- dar a outra faceta da história, a perspectiva tim, dito «Juca Valentim», José Jacinto da do «outro MPLA» como gostam de se lhe Silva Vieira Dias Van Dunem, João Jacob referir. É pena que essa ambição, ao desa- Caetano, dito «Monstro Imortal», e Ber- fiar corajosamente tanta sabedoria esta- nardo Alves Baptista, mais conhecido por belecida, acabe por se revelar a principal «Nito Alves», «não eram burocratas, fraqueza da obra. -

Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola

Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola By Aaron Laurence deGrassi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Professor Gillian P. Hart Professor Peter B. Evans Abstract Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola by Aaron Laurence deGrassi Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Fueled by a massive offshore deep-water oil boom, Angola has since the end of war in 2002 undertaken a huge, complex, and contradictory national reconstruction program whose character and dynamics have yet to be carefully studied and analyzed. What explains the patterns of such projects, who is benefitting from them, and how? The dissertation is grounded in the specific dynamics of cassava production, processing and marketing in two villages in Western Malanje Province in north central Angola. The ways in which Western Malanje’s cassava farmers’ livelihoods are shaped by transport, marketing, and an overall agrarian configuration illustrate how contemporary reconstruction – in the context of an offshore oil boom – has occurred through the specific conjunctures of multiple geo-historical processes associated with settler colonialism, protracted war, and leveraged liberalization. Such an explanation contrasts with previous more narrow emphases on elite enrichment and domination through control of external trade. Infrastructure projects are occurring as part of an agrarian configuration in which patterns of land, roads, and markets have emerged through recursive relations, and which is characterized by concentration, hierarchy and fragmentation. -

Nascimento E Morte Do Poder Popular Em Angola (1974- 1977)

Nascimento e morte do Poder Popular em Angola (1974- 1977) Maria Cristina Portella Ribeiro A partir de 25 de Abril de 1974, quando um golpe militar contra a ditadura chefiada por Marcelo Caetano desencadeia em Portugal a Revolução dos Cravos,1 abre-se em Angola uma nova situação política. A até então colônia portuguesa começará a viver um levante popular semelhante em muitos aspectos ao verificado na metrópole. Ambos terão como base a questão colonial e a democracia e irão dar origem a modelos de auto- organização da população. Assim como os portugueses, os trabalhadores de Angola, brancos e negros, começam a fazer greves e manifestações para exigir direitos. Nos musseques,2 os seus habitantes, quase todos negros, irão expulsar os informantes da PIDE-DGS,3 travestidos de comerciantes, organizar comitês para se defenderem das agressões da extrema-direita branca e garantir o abastecimento de gêneros de primeira necessidade. Na universidade e nas escolas secundárias, os estudantes irão criar os seus órgãos de representação e tentar vincular a sua luta à do conjunto da população. Nos quartéis, soldados brancos irão recusar-se a continuar a participar na guerra contra os movimentos de libertação, enquanto soldados negros vão exigir serem eles a policiar os musseques para defender os seus irmãos africanos. A independência de Angola começa a ser defendida timidamente por setores da população. Doutoranda do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História Social (PPGHIS/UFRJ) e bolsista do CNPq. 1 Nome pelo qual ficou conhecida a revolução que derrubou a ditadura do Estado Novo em Portugal, instaurou a democracia e chegou a questionar as bases do sistema capitalista no país. -

A History of Angola

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 11-2017 A History of Angola Jeremy R. Ball Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Ball, Jeremy. "The History of Angola." In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. (Article published online November 2017). http://africanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/ 9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-180 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History of Angola Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History The History of Angola Jeremy Ball Subject: Central Africa, Colonial Conquest and Rule Online Publication Date: Nov 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.180 Summary and Keywords Angola’s contemporary political boundaries resulted from 20th-century colonialism. The roots of Angola, however, reach far into the past. When Portuguese caravels arrived in the Congo River estuary in the late 15th century, independent African polities dotted this vast region. Some people lived in populous, hierarchical states such as the Kingdom of Kongo, but most lived in smaller political entities centered on lineage-village settlements. The Portuguese colony of Angola grew out of a settlement established at Luanda Bay in 1576. From its inception, Portuguese Angola existed to profit from the transatlantic slave trade, which became the colony’s economic foundation for the next three centuries. A Luso- African population and a creole culture developed in the colonial nuclei of Luanda and Benguela (founded 1617). -

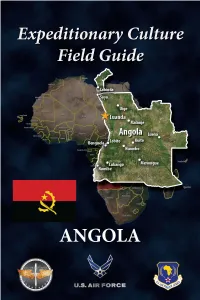

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values.