Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Angola Background Paper

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM ANGOLA UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, APRIL 1999 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY INFORMATION UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. PREFACE Angola has been an important source country of refugees and asylum-seekers over a number of years. This paper seeks to define the scope, destination, and causes of their flight. The first and second part of the paper contains information regarding the conditions in the country of origin, which are often invoked by asylum-seekers when submitting their claim for refugee status. The Country Information Unit of UNHCR's Centre for Documentation and Research (CDR) conducts its work on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment, with all sources cited. In the third part, the paper provides a statistical overview of refugees and asylum-seekers from Angola in the main European asylum countries, describing current trends in the number and origin of asylum requests as well as the results of their status determination. The data are derived from government statistics made available to UNHCR and are compiled by its Statistical Unit. Table of Contents 1. -

Angola Cabinda

Armed Conflicts Report - Angola Cabinda Armed Conflicts Report Angola-Cabinda (1994 - first combat deaths) Update: January 2007 Summary Type of Conflict Parties to the Conflict Status of the Fighting Number of Deaths Political Developments Background Arms Sources Economic Factors Summary: 2006 The Angolan government signed the Memorandum of Understanding in July 2006, a peace agreement with one faction of the rebel group FLEC (Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave). Because of this, and few reported conflict related deaths over the past two years (less than 25 per year), this armed conflict is now deemed to have ended. 2005 Government troops and rebels clashed on several occasions and the Angolan army continued to be accused of human rights abuses in the region. Over 50,000 refugees returned to Cabinda this year. 2004 There were few reported violent incidences this year. Following early reports of human rights abuses by both sides of the conflict, a visit by a UN representative to the region noted significant progress. Later, a human rights group monitoring the situation in Cabinda accused government security forces of human rights abuses. 50,000 refugees repatriated during the year, short of the UNHCR’s goal of 90,000. 2003 Rebel bands remained active even as the government reached a “clean up” phase of the military campaign in the Cabinda enclave that began in 2002. Both sides were accused of human rights violations and at least 50 civilians died. Type of Conflict: State formation Parties to the Conflict: 1) Government, led by President Jose Eduardo dos Santos: Ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA); 2) Rebels: The two main rebel groups, the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave (FLEC) and the Front for the Liberation of the Cabinda Enclave Cabinda Armed Forces (FLEC FAC), announced their merger on 8 September 2004. -

Saved by the Civil War: African 'Loyalists' in the Portuguese Armed Forces and Angola's Transition to Independence

Saved by the civil war: African ‘loyalists’ in the Portuguese armed forces and Angola’s transition to independence Pedro Aires Oliveira Instituto de História Contemporânea, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 1069-061 Lisboa [email protected] Abstract: The article examines the trajectories of ‘loyal’ African troops in Angola before and after the demise of Portugal’s authoritarian regime in 1974. It starts by placing the ‘Africanization’ drive of the Portuguese counterinsurgency campaign in a historical perspective; it then explores the rocky transition from colonial rule to independence in the territory between April 1974 and November 1975, describing the course of action taken by the Portuguese authorities vis-à-vis their former collaborators in the security forces. A concluding section draws a comparison between the fate of Portugal’s loyalists in Angola and the one experienced by similar groups in other ex-Portuguese colonies. The choice of Angola has the advantage of allowing us to look into a complex scenario in which the competition amongst rival nationalist groups, and a number of external factors, helped to produce a more ambiguous outcome for some of the empire’s local collaborators than what might have been otherwise expected. Keywords: Angola; colonial troops; Loyalists; counter-insurgency; Decolonization The dissolution of Portugal’s overseas empire in 1975 happened after a protracted counterinsurgency war which took place in three of its African territories (Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique), a 13 year conflict (1961- 74) that put an enormous strain on the limited demographic and economic resources of what was then Western Europe’s poorest and most undeveloped 1 state. -

A Military History of the Angolan Armed Forces from the 1960S Onwards—As Told by Former Combatants

Evolutions10.qxd 2005/09/28 12:10 PM Page 7 CHAPTER ONE A military history of the Angolan Armed Forces from the 1960s onwards—as told by former combatants Ana Leão and Martin Rupiya1 INTRODUCTION The history of the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) remains largely unwritten—yet, understanding the FAA’s development is undoubtedly important both for future Angolan generations as well as for other sub- Saharan African countries. The FAA must first and foremost be understood as a result of several processes of integration—processes that began in the very early days of the struggle against Portuguese colonialism and ended with the April 2002 Memorandum of Understanding. Today’s FAA is a result of the integration of the armed forces of the three liberation movements that fought against the Portuguese—the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), the FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola) and UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola). This was a process that developed over more than 30 years. The various phases that characterise the formation and development of the FAA are closely related to Angola’s recent political history, particularly the advent of independence in 1975 and the civil war that ensued. This chapter introduces that history with a view to contributing to a clearer understanding of the development of the FAA and its current role in a peaceful Angola. As will be discussed, while the FAA was formerly established in 1992 following the provisions of the Bicesse Peace Accords, its origins go back to: 7 Evolutions10.qxd 2005/09/28 12:10 PM Page 8 8 Evolutions & Revolutions • the Popular Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA) and the integration over more than three decades of elements of the Portuguese Colonial Army; • the FNLA’s Army for the National Liberation of Angola (ELNA); and • UNITA’s Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FALA). -

A Rebelião Interna No Mpla Em 1977 E As Confusões No Noticiário De Zero Hora E Correio Do Povo

QUEM SÃO OS REBELDES, AFINAL? A REBELIÃO INTERNA NO MPLA EM 1977 E AS CONFUSÕES NO NOTICIÁRIO DE ZERO HORA E CORREIO DO POVO. MAURO LUIZ BARBOSA MARQUES 1 O presente artigo buscar analisar as dicotomias e as abordagens contraditórias dos periódicos gaúchos Zero Hora e Correio do Povo 2 durante a crise interna do MPLA 3, partido governante em Angola no ano de 1977. Angola foi a principal possessão lusitana até 1975 – ano da ruptura colonial angolana -, quando a partir de um cenário marcado por violentas disputas internas e externas, parte do contexto internacional daquele período, houve caminhos e descaminhos na consolidação deste novo Estado Nacional pós colonização, especialmente entre os anos 1975 e 1979 quando Agostinho Neto 4 e o MPLA comandaram o primeiro governo independente contemporâneo de Angola. Um destes fatores de consolidação política de um novo Estado Nacional se deu na disputa da esfera superior de poder no interior do MPLA durante a condução do Estado Nacional, em maio de 1977. Algo tradicional, em especial na tradição africana contemporânea permeada com debilidades nas estruturas estatais e disputas palacianas. 1 Mestre em História pela UFRGS (Porto Alegre/RS) atua na rede pública estadual e municipal na cidade de São Leopoldo (RS). 2 Estes periódicos tinham grande circulação estadual e somados tinham uma tiragem superior a cem mil exemplares no período analisado por esta pesquisa, conforme informado na capa dos mesmos (nota do autor). 3 O médico e poeta Antonio Agostinho Neto formou o MPLA (Movimento Popular para Libertação de Angola), que tinha como referência o bloco socialista e contou com o apoio decisivo da URSS e dos cubanos na hora da ruptura com Portugal em novembro de 1975. -

Angola and the MPLA

No One Can Stop the Rain: Angola and the MPLA http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.af000173 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org No One Can Stop the Rain: Angola and the MPLA Alternative title No One Can Stop the Rain: Angola and the MPLA Author/Creator Houser, George M.; Davis, Jennifer; Rogers, Susan Geiger; Shore, Herb Publisher Africa Fund Date 1976-07 Resource type Pamphlets Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, South Africa, United States, Namibia, Zambia Coverage (temporal) 1482 - 1976 Source Africa Action Archive Rights By kind permission of Jennifer Davis, David G. -

Angola and the Mplu J-- by Jennifer Davis, George M

angola and the mplu J-- by Jennifer Davis, George M. Houser, Susan Rogers and Herb Shore published by THE AFRICA FUND 305 E. 46th St. New York, N.Y. 10017 ANGOLA eLllSO DtWieJQI)<Ail - · -O rm.el~ co...._ l'hme -of CO{I(elflf! Of t:I~UIUCUfio Wt\111 difl~11romthi! O isea1 -- l n dau l l)lllf -- bldcl.lU fa.d + + ATLA.N TIC OC£AN + + ,.. + ... + NAM IBIA n..~·w·----~~-~~j> _,., ..,,,.~, 1'1/ti.W vtrh"~- • • ..,,._,... b lh u.ud ·"•'"""' f•UI.J'NO lOft ltt:" ..O oc:TQIIIliiUU price $1.50 NO ONE CAN STOP THE RAIN Angola and The MPLA by George Houser Jennifer Davis Herb Shore Susan Rogers THE AFRICA FUND (associated with the American Committee on Africa) 305 East 46th Street New York, New York 10017 (212) 838-5030 r----1ea = I No One Can Stop The Rain Here in prison rage contained in my breast I patiently wait for the clouds to gather 1 blown by the wind of history j l Noone l can stop the rain 1 -from "Here in Prison" by Agostinho Neto PIDE Prison Luanda, July 1960 I PREFACE This pamphlet represents a collaborative effort. Originally, much of the material included was written by George Houser as sections of an Angola chapter for a book on liberation move ments in southern Africa. Events overtook the writing of that book. Following the April, 1974 coup in Portugal and subse quent rapid changes in Guinea Bissau, Angola and Mozambique, it became impossible to find the necessary time for re-writing and updating the book manuscript in its entirety. -

As Memórias Do 27 De Maio De 1977 Em Angola

As memórias do 27 de maio de 1977 em Angola Inácio Luiz Guimarães Marques 27 de maio de 1977. Há 34 anos aconteceu em Angola um dos episódios mais polêmicos, controversos e violentos de sua história recente. 18 meses após a Independência, proclamada pelo MPLA em 11 de novembro de 1975, a crise nitista evidenciou o alcance das contradições internas no MPLA. A expressão nitista, ou nitismo, refere-se a um dos principais lideres da contestação, Alves Bernardo Baptista, Nito Alves, guerrilheiro da 1ª região Político-militar durante a guerra de libertação, que aparece com mais evidencia no Movimento durante o Congresso de Lusaka, em 1974, defendendo as posições do presidente Agostinho Neto. Como aliado chegou aos altos escalões do Movimento, o que lhe rendeu o cargo de Ministro da Administração Interna no primeiro governo independente, em 1975. Durante o ano de 1976, grosso modo, sua posição político-ideológica – a favor do estabelecimento de um governo marxista- leninista – foi progressivamente conquistando adeptos e, ao mesmo tempo, provocando atritos com o Governo, que ao contrário insistia em uma chamada Revolução democrática e popular que não ameaçasse sua legitimidade. Em outubro deste mesmo ano foi acusado, juntamente com seus principais aliados, José-Van-Dunem e Sita Vales, de traição, o que lhe custou a perda do cargo de Ministro. Apesar disso, não cedeu aos pedidos para que se calasse, o que rendeu a Nito Alves – e também a Van-Dunem – a expulsão formal em 20 de Maio de 1977 dos quadros do Movimento. Apenas uma semana depois, no dia 27, tentaria sem sucesso derrubar o Governo. -

Cabinda Notes on a Soon-To-Be-Forgotten War

INSTITUTE FOR Cabinda Notes on a soon-to-be-forgotten war João Gomes Porto Institute for Security Studies SECURITY STUDIES ISS Paper 77 • August 2003 Price: R10.00 CABINDA’S YEAR OF WAR: 2002 the Angolan government allegedly used newly- incorporated UNITA soldiers to “all but vanquish the The government of Angola considers… that it is indis- splintered separatist factions of the FLEC.”6 pensable to extend the climate of peace achieved in the whole territory and hence to keep its firm com- When the Angolan government and UNITA signed the mitment of finding a peaceful solution to the issue of Memorandum of Understanding on 4 April 2002, the Cabinda, within the Constitutional legality in force, situation in Cabinda had been relatively quiet for taking into account the interests of the country and the several months. Soon after, however, reports of clashes local population.1 in the Buco-Zau military region between government forces and the separatists began pouring out of Cabinda is the Cabindan’s hell.2 Cabinda. The FAA gradually advanced to the heart of the rebel-held territory, and by the end of October War in Angola may only now be over, 15 2002 it had destroyed Kungo-Shonzo, months after the government and UNITA the FLEC-FAC’s (Front for the Liberation (National Union for the Total Indepen- of the Enclave of Cabinda-Armed Forces dence of Angola) formally ended the The FAA are of Cabinda) main base in the munici- civil war that has pitted them against one pality of Buco-Zau. Situated 110km from another for the last three decades. -

Angola's Foreign Policy

ͻͺ ANGOLA’S AFRICA POLICY PAULA CRISTINA ROQUE ʹͲͳ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Paula Cristina Roque is currently finalising her PhD on wartime guerrilla governance (using Angola and South Sudan as case studies) at Oxford University. She is also a founding member of the South Sudan Centre for Strategic and policy Studies in Juba. She was previously the senior analyst for Southern Africa (covering Angola and Mozambique) with the International Crisis Group, and has worked as a consultant for several organizations in South Sudan and Angola. From 2008-2010 she was the Horn of Africa senior researcher, also covering Angola, for the Institute for Security Studies in Pretoria. ABOUT THE EGMONT PAPERS The Egmont Papers are published by Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an independent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision-making process. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 Operating Principles: permanent interests and shifting levers . 4 Bilateral Miscalculations in Guinea-Bissau and Cote D’Ivoire . 8 Democratic Republic of Congo and Republic of Congo: National Security Interests. 11 Multilateral Engagements: AU, Regional Organisations and the ICGLR . 16 Conclusion . 21 1 INTRODUCTION Angola is experiencing an existential transition that will change the way power in the country is reconfigured and projected. -

Cuba E União Soviética Em Angola: 1977

Cuba e União Soviética em Angola: 1977 Cristina Portella Doutoranda em História Social Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil) Luis Leiria Jornalista Portal Esquerda.net (Portugal) Resumo: No dia 27 de maio de 1977, em Angola, o governo de Agostinho Neto desencadeou um processo repressivo que ocasionou a morte de milhares de aderentes do MPLA. O objetivo, de acordo com a justificação oficial, seria impedir um golpe de Estado liderado pelo ex-ministro da Administração Interna Nito Alves. Nessa altura, estavam presentes em Angola tropas cubanas e oficiais da URSS. A historiografia oferece várias interpretações para este episódio, marcante na história do país recém-independente. Este artigo discute os fatos, as causas e as consequências do “27 de Maio”, à luz de documentos cubanos recentemente desclassificados, reunidos por Piero Gleijeses, professor de política externa norte-americana na School of Advanced International Studies da Universidade Johns Hopkins, no portal do Wilson Center Digital Archive International - History Declassified. Palavras-chave: 1. Angola, 2. MPLA, 3. Cuba, 4. União Soviética Abstract: On May 27, 1977, in Angola, the government of Agostinho Neto triggered a repressive process that led to the deaths of thousands of MPLA members. The goal, according to official justification, would be to prevent a coup led by former Home Minister Nito Alves. At that time, Cuban troops and USSR officers were present in Angola. Historiography offers several interpretations for this episode, striking in the history of the newly independent country. This article discusses the facts, causes, and consequences of “May 27,” in light of recently declassified Cuban documents, gathered by Piero Gleijeses, a professor of US foreign policy at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Wilson Center Digital Archive International Portal - History Declassified Keywords: 1. -

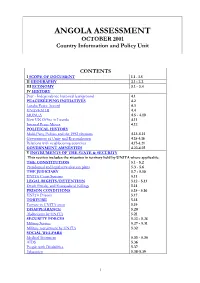

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit

ANGOLA ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2001 Country Information and Policy Unit CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 - 1.5 II GEOGRAPHY 2.1 - 2.2 III ECONOMY 3.1 - 3.4 IV HISTORY Post - Independence historical background 4.1 PEACEKEEPING INITIATIVES 4.2 Lusaka Peace Accord 4.3 UNAVEM III 4.4 MONUA 4.5 - 4.10 New UN Office in Luanda 4.11 Internal Peace Moves 4.12 POLITICAL HISTORY Multi-Party Politics and the 1992 elections 4.13-4.14 Government of Unity and Reconciliation 4.15-4.16 Relations with neighbouring countries 4.17-4.21 GOVERNMENT AMNESTIES 4.22-4.25 V INSTRUMENTS OF THE STATE & SECURITY This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable. THE CONSTITUTION 5.1 - 5.2 Presidential and legislative election plans 5.3 - 5.6 THE JUDICIARY 5.7 - 5.10 UNITA Court Systems 5.11 LEGAL RIGHTS/DETENTION 5.12 - 5.13 Death Penalty and Extrajudicial Killings 5.14 PRISON CONDITIONS 5.15 - 5.16 UNITA Prisons 5.17 TORTURE 5.18 Torture in UNITA areas 5.19 DISAPPEARANCE 5.20 Abductions by UNITA 5.21 SECURITY FORCES 5.22 - 5.26 Military Service 5.27 - 5.31 Military recruitment by UNITA 5.32 SOCIAL WELFARE Medical Treatment 5.33 - 5.35 AIDS 5.36 People with Disabilities 5.37 Education 5.38-5.39 1 VI HUMAN RIGHTS- GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE SITUATION Introduction 6.1 SECURITY SITUATION Recent developments in the Civil War 6.2 - 6.17 Security situation in Luanda 6.18 - 6.19 Landmines 6.20 - 6.22 Human Rights monitoring 6.23 - 6.26 VII SPECIFIC GROUPS REFUGEES 7.1 Internally Displaced Persons & Humanitarian Situation 7.2-7.5 UNITA 7.6-7.8 Recent Political History of UNITA 7.9-7.12 UNITA-R 7.13-7.14 UNITA Military Wing 7.15-7.20 Surrendering UNITA Fighters 7.21 Sanctions against UNITA 7.22-7.25 F.L.E.C/CABINDANS 7.26 History of FLEC 7.27-7.28 Recent FLEC activity 7.29-7.34 The future of Cabindan separatists 7.35 ETHNIC GROUPS 7.36-7.37 Bakongo 7.38-7.46 WOMEN 7.47 Discrimination against women 7.48-7.59 CHILDREN 7.50-7.55 VIII RESPECT FOR CIVIL LIBERTIES This section includes the situation in territory held by UNITA where applicable.