A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century

Politics, Commerce, and Colonization in Angola at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century John Whitney Harvey Dissertação em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos Orientador: Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim Setembro, 2012 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em História Moderna e dos Descobrimentos realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Pedro Cardim e a coorientação científica do Professor Doutor Diogo Ramada Curto. I dedicate this dissertation to my father, Charles A. Harvey Jr. (1949-2009), whose wisdom, hard work, and dedication I strive to emulate. The last thing he knew about me was that I was going to study at FCSH, and I hope that I have made him proud. Acknowledgements There are so many people that were instrumental to the production of this dissertation that it would be impossible to include everyone in this space. I want to take the opportunity to thank everyone that supported me emotionally and academically throughout this year. Know that I know who you are, I appreciate everything done for me, and hope to return the support in the future. I would also like to thank the Center for Overseas History for the resources and opportunities afforded to me, as well as all of my professors and classmates that truly enriched my academic career throughout the last two years. There are some people whom without, this would not have been possible. The kindness, friendship, and support shown by Nuno and Luisa throughout this process I will never forget, and I am incredibly grateful and indebted to you both. -

A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade? Boxell, Levi Stanford University 3 March 2016 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/69853/ MPRA Paper No. 69853, posted 06 Mar 2016 12:59 UTC A Drought-Induced African Slave Trade?∗ Levi Boxell† Stanford University First Version: June 6, 2015 This Version: March 4, 2016 Abstract Historians have frequently suggested that droughts helped facilitate the African slave trade. By introducing a previously unused dataset on historical rainfall levels in Africa, I provide the first empirical answer to this hypothesis. I demonstrate how negative rainfall shocks and long-run shifts in the mean level of rainfall increased the number of slaves exported from a given region and can have persistent effects on the level of development today. Using a simple economic model of an individual’s decision to participate in the slave trade, along with observed empirical heterogeneity and historical anecdotes, I argue that consumption smoothing and labor allocation adjustments are the primary causal mechanisms for the negative relationship between droughts and slave exports. These findings contribute to our understanding of the process of selection into the African slave trade and have policy implications for contemporary human trafficking and slavery. JEL Classification: N37, N57, O15, Q54 Keywords: slave trade, climate, droughts, consumption smoothing, human trafficking ∗Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Jiwon Choi, John T. Dalton, James Fenske, Matthew Gentzkow, Namrata Kala, Andres Shahidinejad, Jesse M. Shapiro, and Michael Wong for their comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are mine. †SIEPR, Stanford University (Email: [email protected]) 1 1 Introduction The African slave trade significantly altered modern economic and cultural outcomes (Nunn, 2008). -

Intimate Encounters with the State in Post-War Luanda, Angola

Intimate Encounters with the State in Post-War Luanda, Angola Chloé Buire Les Afriques dans le Monde, CNRS, Pessac, France Abstract: Since the end of the war in 2002, Luanda has become an iconic site of urban transformation in the context of a particularly entrenched oligarchic regime. In practice however, urban dwellers are often confronted with a ‘deregulated system’ that fails to advance a coherent developmental agenda. The paper narrates the trajectory of a family forcibly removed from the old city to the periphery. It shows how city- dwellers experience the control of the party-state through a series of encounters with authority across the city. Questioning the intentionality of a state that appears at the same time omnipotent and elusive, openly violent and subtly hegemonic, the paper reveals the fine mechanisms through which consent is fabricated in the intimacy of the family. In 2001, guerrilla leader Jonas Savimbi is hiding in the hinterlands of Angola; but on the Atlantic coast, the shadows of the civil war are dissipating and the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the ruling party of Angola since 1975, announces ambitious reconstruction works in the capital city Luanda. In an old bairro (neighbourhood) near the city centre, Avo Monteiro, once a cook at one of the best hotels in town, gets the notice that will change the life of his whole family: his house is to be demolished to give way to a new road. A few months later, Savimbi is killed; the peace treaty that unfolds allows the MPLA to extend its control to the entire country and consolidate its grasp on all levels of government. -

Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola

Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola By Aaron Laurence deGrassi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Professor Gillian P. Hart Professor Peter B. Evans Abstract Provisional Reconstructions: Geo-Histories of Infrastructure and Agrarian Configuration in Malanje, Angola by Aaron Laurence deGrassi Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Fueled by a massive offshore deep-water oil boom, Angola has since the end of war in 2002 undertaken a huge, complex, and contradictory national reconstruction program whose character and dynamics have yet to be carefully studied and analyzed. What explains the patterns of such projects, who is benefitting from them, and how? The dissertation is grounded in the specific dynamics of cassava production, processing and marketing in two villages in Western Malanje Province in north central Angola. The ways in which Western Malanje’s cassava farmers’ livelihoods are shaped by transport, marketing, and an overall agrarian configuration illustrate how contemporary reconstruction – in the context of an offshore oil boom – has occurred through the specific conjunctures of multiple geo-historical processes associated with settler colonialism, protracted war, and leveraged liberalization. Such an explanation contrasts with previous more narrow emphases on elite enrichment and domination through control of external trade. Infrastructure projects are occurring as part of an agrarian configuration in which patterns of land, roads, and markets have emerged through recursive relations, and which is characterized by concentration, hierarchy and fragmentation. -

A History of Angola

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Faculty and Staff Publications By Year Faculty and Staff Publications 11-2017 A History of Angola Jeremy R. Ball Dickinson College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.dickinson.edu/faculty_publications Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Ball, Jeremy. "The History of Angola." In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. (Article published online November 2017). http://africanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/ 9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-180 This article is brought to you for free and open access by Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The History of Angola Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History The History of Angola Jeremy Ball Subject: Central Africa, Colonial Conquest and Rule Online Publication Date: Nov 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.180 Summary and Keywords Angola’s contemporary political boundaries resulted from 20th-century colonialism. The roots of Angola, however, reach far into the past. When Portuguese caravels arrived in the Congo River estuary in the late 15th century, independent African polities dotted this vast region. Some people lived in populous, hierarchical states such as the Kingdom of Kongo, but most lived in smaller political entities centered on lineage-village settlements. The Portuguese colony of Angola grew out of a settlement established at Luanda Bay in 1576. From its inception, Portuguese Angola existed to profit from the transatlantic slave trade, which became the colony’s economic foundation for the next three centuries. A Luso- African population and a creole culture developed in the colonial nuclei of Luanda and Benguela (founded 1617). -

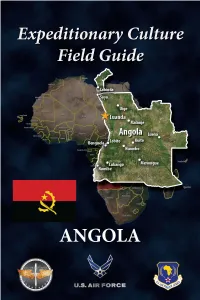

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Angola After 40 Years of Independence: the Way Ahead

Africa Conference Meeting Summary Angola after 40 Years of Independence: The Way Ahead 12 November 2015 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2016. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Angola after 40 Years of Independence: The Way Ahead Introduction On 12 November 2015, Chatham House’s Africa Programme hosted a conference to mark the 40th anniversary of Angola’s independence. Since the 2002 Luena Memorandum of Understanding that ended one of the continent’s longest civil wars, Angola has enjoyed a prolonged period of extractives-driven growth. But the new realities of low commodity prices and depleting oil resources are creating pressure for economic diversification. -

The Economy of Angola: from Independence to the 2008 Worldwide Crisis

THE ECONOMY OF ANGOLA: FROM INDEPENDENCE TO THE 2008 WORLDWIDE CRISIS Jonuel Gonçalves* ABSTRACT Since abolition of slavery, the Angolan economy has been dependant upon production of primary goods. Throughout most of the 20th Century, coffee and diamonds were the main exports. With the discovery of offshore oil fields in the early 1970s, Angola became a major oil exporter. Since then, the Angolan economy has revolved almost entirely around oil, which now pays for everything, including food imports to compensate for lost domestic production, machinery replacement for industry, and the war effort. Against this background, the 2008 crisis left the Angolan economy in an extremely critical condition, owing to the drop in oil prices. This article undertakes an historical analysis of Angola, from independence up until the 2008 crisis and its aftermath. 1 INTRODUCTION After independence, on November 11, 1975, Angola spent most of the interven- ing period plunged in warfare, and only in the past eight years1 has it enjoyed peace. This had grave repercussions on the Angolan economy which, currently, is the second-largest in southern Africa. Angola’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is second to, but much smaller than, that of South Africa. It has surpassed the GDP of Zimbabwe, the economy of which is in a deplorable state. Aside from the effects of war, other elements that hamper Angolan eco- nomic performance are a lack of qualified human resources and the persistence of extractive activities. According to domestic and international forecasts, by the end of 2010 An- golan GDP will amount to US$ 87.5 billion (calculated by the official exchange rate TCO). -

The Black Woman from the Countryside in Angolan Literature

A Body to Make Luanda: The Black Woman from the Countryside in Angolan Literature JÚLIA GARRAIO Universidade de Coimbra Abstract: In this article, I examine how the image of the black woman from the countryside who moves to Luanda was developed at three key moments in Angolan literature as a means of constructing national identity. I focus on three prose works: Alfredo Troni’s Nga Mutúri (1882); António Cardoso’s short story “Linda,” from A Casa da Mãezinha (1980); and Fragata de Morais’s short story “Martinha,” from Momento de Ilusão (2000). Keywords: Alfredo Troni; António Cardoso; Fragata de Morais; Gender; lieux de mémoire In this article, I examine how the image of the black woman from the countryside who moves to Luanda was developed at three key moments in Angolan literature as a means of constructing national identity. 1 My analysis focuses on the following works, all of which participated in the construction of Luanda as an Angolan lieu de mémoire: Nga Mutúri (1882), a novella by Alfredo Troni about mestiço Luandan society in the second half of the nineteenth century; “Linda,” a short story from A Casa da Mãezinha, by António Cardoso, an emblematic work 1 This article results from the project “De S. Paulo de Luanda a Luuanda, de Lourenço Marques a Maputo: capitais coloniais em tempos pós-coloniais” (PTDC/CLE- LLI/122229/2010 - FCOMP-01- 0124-FEDER- 019830), which was financed by Fundos FEDER through the Programa Operacional Factores de Competitividade and by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia. 177 Garraio of anti-colonial literature that was written in 1962 from within a PIDE prison; and “Martinha,” a short story by Fragata de Morais from Momento de Ilusão (2000), which takes us to the last years of the civil war and to the city’s demographic explosion as a refuge sought by those displaced by the conflict. -

An Environmental History of Angola

Book Review Page 1 of 2 An environmental history of Angola BOOK TITLE: Wildlife at war in Angola: The In stark contrast to other countries in the southern third of Africa, very little is known about the ecosystems, rise and fall of an African Eden vegetation and wildlife of Angola. In almost 500 years of colonial rule, the nation of Portugal profited from the extraction from Angola of resources in the form of slaves, ivory, timber, diamonds and oil, but re-invested very little BOOK COVER: into development, or into the conservation of the country’s considerable wealth and diversity of landscapes and wildlife. The remarkably small settler community was dominated by poor and relatively uneducated Portuguese citizens, including a large proportion of exiled criminals. However, in the early 1970s, moves were afoot to strengthen the Angolan national park system, and to place the management of parks on a sound scientific footing. It was a brief but promising period in Angola’s conservation history – one in which this book’s author, Brian Huntley, played an important role. Huntley was appointed in 1971 as a scientific advisor to the colonial government, and was broadly tasked with documenting the status of the existing protected area network, and making proposals for their management and, where necessary, expansion. Unfortunately, the events that followed Angola’s independence in 1975 (including open warfare between rival liberation movements, and invasion of Angola by the South African Defence Force) forced Huntley to leave. However, he never lost interest in Angola, and the collapse of South Africa’s apartheid policies in 1990 made it possible for him to re-establish contact with Angolan colleagues and to regularly follow up on initiatives related to conservation and ecosystem management in Angola over the next 25 years. -

Angola's People

In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp20002 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org In the Eye of the Storm: Angola's People Author/Creator Davidson, Basil Publisher Anchor Books Anchor Press/Doubleday Date 1973-00-00 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Angola, Zambia, Congo, the Democratic Republic of the, Congo Coverage (temporal) 1600 - 1972 Rights By kind permission of Basil R. Davidson. Description This book provides both historical background and a description of Davidson's trip to eastern Angola with MPLA guerrilla forces. -

Angola, August 2001

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Angola, August 2001 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question.