Finnish Women Artists in the Modern World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

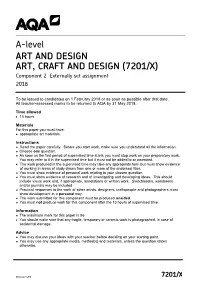

ART, CRAFT and DESIGN (7201/X) Component 2 Externally Set Assignment 2018

A-level ART AND DESIGN ART, CRAFT AND DESIGN (7201/X) Component 2 Externally set assignment 2018 To be issued to candidates on 1 February 2018 or as soon as possible after that date. All teacher-assessed marks to be returned to AQA by 31 May 2018. Time allowed • 15 hours Materials For this paper you must have: appropriate art materials. Instructions Read the paper carefully. Before you start work, make sure you understand all the information. Choose one question. As soon as the first period of supervised time starts you must stop work on your preparatory work. You may refer to it in the supervised time but it must not be added to or amended. • The work produced in the supervised time may take any appropriate form but must show evidence of working in areas of study drawn from one or more of the endorsed titles. You must show evidence of personal work relating to your chosen question. You must show evidence of research and of investigating and developing ideas. This should include visual work and, if appropriate, annotations or written work. Sketchbooks, workbooks and/or journals may be included. Practical responses to the work of other artists, designers, craftspeople and photographers must show development in a personal way. The work submitted for this component must be produced unaided. You must not produce work for this component after the 15 hours of supervised time. Information The maximum mark for this paper is 96. • You should make sure that any fragile, temporary or ceramic work is photographed, in case of accidental damage. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

Vieraita Vaikutteita Karsimassa Helene Schjerfbeck Ja Juho Rissanen Sukupuoli, Luokka Ja Suomen Taiteen Rakentuminen 1910-20

Vieraita vaikutteita karsimassa Helene Schjerfbeck ja Juho Rissanen Sukupuoli, luokka ja Suomen taiteen rakentuminen 1910–20 -luvulla Esitetään Helsingin yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi pienessä juhlasalissa perjantaina 21. helmikuuta 2014 klo 12. !"# $ %& ' () * "! Väitöskirja on prosessi – ”art as existence”, taidehistoriaa ja elämää. Vuosia sitten muuan ystävä esitti, että vasta akateeminen kirjoittaminen on oikeaa kirjoittamista. Päätin testata väitteen. Prosessi ainakin on ollut antoisa, ja sen aikana olen saanut myös tukea ja ymmärrystä: kollegoilta Helsingin yliopistossa ja muissa yliopistoissa, ystäviltä ja perheeltä. Tutkimuksen alkuun en olisi kuitenkaan päässyt ilman taidehistorian emeritoja, kiitos heille. Silloinen taidehistorian professori Riitta Nikula vastaanotti mutkattomasti vuosien jälkeen takaisin yliopistolle, samoin kuin hänen kaimansa, professori Riitta Konttinen. Jälkimmäisestä Riitasta tuli väitöskirjan toinen ohjaaja. Upean tilaisuuden tutkimustyölle tarjosi toinen ohjaaja, dosentti, yliopistonlehtori Renja Suominen-Kokkonen kutsumalla johtamaansa ”Taidehistorian omakuva” -projektiin, jossa työskentelin kolme vuotta Suomen akatemian rahoituksella. Projekti on ollut melkoinen tutkijakoulu. Sen kautta olen tavannut monia eteviä taidehistorioitsijoita ja visuaalisen kulttuurin tutkijoita. Heitä on ollut Suomesta, Ruotsista, Tanskasta, Norjasta, Britanniasta, Itävallasta, Saksasta ja USA:sta, kun projektimme -

European Revivals from Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange

European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange EUROPEAN REVIVALS From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange FNG Research 1/2020 Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Illustration for the novel, Seven Brothers, by Aleksis Kivi, 1907, watercolour and pencil, 23.5cm x 31.5cm. Ahlström Collection, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Aaltonen European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange European Revivals From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange European Revivals. From Dreams of a Nation to Places of Transnational Exchange FNG Research 1/2020 Publisher Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki Editors-in-Chief Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff and Riitta Ojanperä Editor Hanna-Leena Paloposki Language Revision Gill Crabbe Graphic Design Lagarto / Jaana Jäntti and Arto Tenkanen Printing Nord Print Oy, Helsinki, 2020 Copyright Authors and the Finnish National Gallery Web magazine and web publication https://research.fng.fi/ ISBN 978-952-7371-08-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-7371-09-1 (pdf) ISSN 2343-0850 (FNG Research) Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................. vii ANNA-MARIA VON BONSDORFF AND RIITTA OJANPERÄ VISIONS OF IDENTITY, DREAMS OF A NATION Ossian, Kalevala and Visual Art: a Scottish Perspective ........................... 3 MURDO MACDONALD Nationality and Community in Norwegian Art Criticism around 1900 .................................................. 23 TORE KIRKHOLT Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity: Three Key Images in Focus ...................................................................... 49 FRANCES FOWLE Listening to the Voices: Joan of Arc as a Spirit-Medium in the Celtic Revival .............................. 65 MICHELLE FOOT ARTISTS’ PLACES, LOCATION AND MEANING Inventing Folk Art: Artists’ Colonies in Eastern Europe and their Legacy ............................. -

The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin

The Compass Volume 1 Issue 4 Volume 1, Issue 4, The Compass Article 3 January 2017 Redefining the Gaze: The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin Megan D'Avella Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/thecompass Recommended Citation Megan D'Avella (2017) "Redefining the Gaze: The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin," The Compass: Vol. 1 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/thecompass/vol1/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@Arcadia. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Compass by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@Arcadia. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Redefining the Gaze: The Self-Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin By Megan D’Avella, Arcadia University Introduction manner, males boldly presented themselves through self-imagery.1 This can make early Throughout the history of art, self-portrai- female self-portraiture difficult to read autobi- ture has been explored by artists as means ographically, as a subdued painting does not to emphasize their artistic capabilities, claim necessarily translate into a subdued woman. their importance in modern art, and solidify Keeping in mind the traditional stan- their existence. The work accomplished by dard of female portraiture, the un-idealized female artists, however, must be considered self-representations that Helen Schjerfbeck, separately from the overall genre of portrai- Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin ture. Women in the early twentieth century painted were no small statement at the turn of needed to approach the canvas with careful the century. -

Uusinta Kirjallisuudentutkimusta

UUSINTA KIRJALLISUDENTUTKIMUSTA Uusinta kirjallisuudentutkimusta Aarnio, Juuso, Rhetoric and Representation. Exploring the Cultural Meaning of the Natural Sciences in Contemporary Popular Science Writing and Literature. – [Hki : Juuso Aarnio], 2008. – 505 s. – Diss. Helsingin yliopisto. Andersson Wretmark, Astrid, Tito Colliander och den ryska heligheten. – Skellefteå : Artos, 2008. – 182 s. Atilla, Jorma, Bulgarianturkkilainen romaani 1960luvulla. – Turku : Turun yliopisto, 2008. – 222 s. – Väitösk. Turun yliopisto. – Turun yliopiston julkaisuja. Sarja C, Scripta lingua Fennica edita 276. Cederholm, Per-Erik, Juhani Aho i Sverige. Pressmottagande och Nobelpriskandidatur. – Sthlm : Stockholm University, 2008. – 117 s. – Stockholm Studies in Finnish Language and Literature 12. Comparative Approaches to European and Nordic Modernisms. Edited by Mats Jansson, Janna Kantola, Jakob Lothe and H. K. Riikonen. – Hki : Palmenia, 2008. – 238 s. – Palmenia-sarja 39. Eilittä, Leena, Ingeborg Bachmann’s utopia and disillusionment. Introduction. – Hki : Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, 2008. – 164 s. – Suomalaisen tiedeakatemian toimituksia. Humaniora 347. Enckell, Emelie. Över språkets gränser. En presentation av diktaren Aaro Hellaakoski. – [Hfors : Emelie Enckell], 2008. – 141 s. Forssell, Pia, J. L. Runebergs samlade skrifter i textkritisk belysning. – [Hfors : Pia Forssell], 2008. – 247 s. – Diss. Helsingfors universitet. Gränser i nordisk litteratur = Borders in Nordic Literature. IASS XXVI 2006. Vol. 1–2. Utgivare = edited by Clas Zilliacus, redaktörer = coeditors: Heidi Grönstrand & Ulrika Gustafsson. – Åbo : Åbo Akademis förlag, 2008. – 752 s. Hakapää, Jyrki, Kirjan tie lukijalle. Kirjakauppojen vakiintuminen Suomessa 1740–1860. – Hki: SKS, 2008. – 466 s. – Väitösk. Helsingin yliopisto. – Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 1166. Homeroksesta Hessu Hopoon. Antiikin traditioiden vaikutus myöhempään kirjallisuuteen. Toimittaneet Janna Kantola ja Heta Pyrhönen. – Hki : SKS, 2008. – 280 s. – Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran toimituksia 1184. -

Artisti Finlandesi in Italia E La Rinascita Della Pittura Murale in Finlandia Tra Otto E Novecento

DOTTORATO DI RICERCA in Strumenti e metodi per la Storia dell’arte XXII CICLO coordinatore prof.ssa Silvia Danesi Squarzina Dipartimento di Storia dell’arte Università degli Studi di Roma ‘Sapienza’ Titolo della tesi di dottorato: “Perché vai in Italia?” – Artisti finlandesi in Italia e la rinascita della pittura murale in Finlandia tra Otto e Novecento Candidato: dott.ssa Maria Stella Bottai Coordinatore del dottorato: prof.ssa Silvia Danesi Squarzina Relatore di tesi per parte italiana: prof.ssa Antonella Sbrilli Consulente esterno per parte finlandese: prof.ssa Johanna Vakkari (Helsinki University) DOTTORATO DI RICERCA in Strumenti e metodi per la Storia dell’arte XXII CICLO coordinatore prof.ssa Silvia Danesi Squarzina Dipartimento di Storia dell’arte Università degli Studi di Roma ‘Sapienza’ Titolo della tesi di dottorato: “Perché vai in Italia?” – Artisti finlandesi in Italia e la rinascita della pittura murale in Finlandia tra Otto e Novecento Relazione del tutor sulla tesi di ricerca della dottoranda BOTTAI M. STELLA a.a. 2008-2009 Candidato: dott.ssa Maria Stella Bottai Coordinatore del dottorato: prof.ssa Silvia Danesi Squarzina Relatore di tesi per parte italiana: prof.ssa Antonella Sbrilli Consulente esterno per parte finlandese: prof.ssa Johanna Vakkari (Helsinki University) “Perché vai in Italia?” – Artisti finlandesi in Italia e la rinascita della pittura murale in Finlandia tra Otto e Novecento 1. Obiettivi della ricerca La ricerca di dottorato della dott.ssa Maria Stella Bottai ha indagato i rapporti artistici intercorsi tra la Finlandia e l’Italia alla fine dell’Ottocento e in particolare il ruolo dell’arte italiana nella rinascita della pittura murale nel paese scandinavo. -

Franciska Sundholm

3 | Suomalainen polaariretkikunta Lapissa 1882–1884 FRANCISKA SUNDHOLM WILHELM RAMSAY Livslång vandring i Fennoskandia FINSKA VETENSKAPS- SOCIETETEN 2020 SOCIETAS SCIENTIARUM FENNICA Finska Vetenskaps-Societeten, grundad 1838, är Finlands äldsta vetenskapsakademi, som publicerar forskning, utdelar stipendier och pris, tar initiativ och håller möten med föredrag. Societeten inledde 1996 ett publiceringssamarbete med syskonakademin Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Vuonna 1838 perustettu Suomen Tiedeseura on Suomen vanhin tiedeakatemia, joka julkaisee tutkimuksia, myöntää tutkimusavustuksia ja palkintoja, tekee aloitteita ja järjestää kokouksia. Seura aloitti 1996 julkaisuyhteistyön sisarjärjestönsä Suomalaisen Tiedeakatemian kanssa. The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, founded in 1838, is the oldest scholarly academy of Finland. It publishes research, awards research grants and prizes, takes initiatives and organizes meetings. In 1996 the Society established cooperation with its sister organizarion the Finnish Academy of Sciences and Letters. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk Serien, som grundades år 1857, publicerar undersökningar om Finlands natur, befolkning och samhällsförhållanden. Utkommer med oregelbundna intervaller. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur och folk utges inom ramen för publiceringssamarbetet med Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. Vuonna 1857 perustettu sarja julkaisee Suomen luontoa, väestöä ja yhteiskuntaoloja käsitteleviä tutkielmia. Ilmestyy epäsäännöllisin välein. Bidrag till kännedom av Finlands natur -

Anna Möller-Sibelius MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL 2007 Anna Möller-Sibelius (F

Anna Möller-Sibelius MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL 2007 Anna Möller-Sibelius (f. 1971) är forskare och kritiker Pärm, foto: Anna Möller-Sibelius Åbo Akademis förlag Biskopsgatan 13, FIN-20500 ÅBO, Finland Tel. int. +358-2-215 3292 Fax int. + 358-2-215 4490 E-post: [email protected] http://www.abo.fi/stiftelsen/forlag/ Distribution: Oy Tibo-Trading Ab PB 33, FIN-21601 PARGAS, Finland Tel. int. +358-2-454 9200 Fax. int. +358-2-454 9220 E-post: [email protected] http://www.tibo.net MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL En tematisk analys av kvinnan och tiden i Solveig von Schoultz poesi Anna Möller-Sibelius ÅBO 2007 ÅBO AKADEMIS FÖRLAG – ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY PRESS CIP Cataloguing in Publication Möller-Sibelius, Anna Mänskoblivandets läggspel : en tematisk analys av kvinnan och tiden i Solveig von Schoultz poesi / Anna Möller-Sibelius. - Åbo : Åbo Akademis förlag, 2007. Diss.: Åbo Akademi. – Summary. ISBN 978-951-765-372-5 ISBN 978-951-765-372-5 ISBN 978-951-765-372-2 (digital) Åbo Akademis tryckeri Åbo 2007 Och hur kan det ta så lång tid att börja förstå sig själv och andra, hur kan det dröja så länge innan man blir mänska? Varje dikt är en bit i mänskoblivandets läggspel som väl aldrig blir färdigt. (Den heliga oron) Lika litet som livet kommer med definitiva lösningar, lika litet kan författaren göra det när han lägger pussel med bitar ur det vi kallar verklighet. Men man vet vad man hoppas på. (Ur författarens verkstad) Nu när jag ser tillbaka tycker jag att det under alltsammans går en envis strävan att komma vidare, jag menar: att genom att helt och fullt bejaka det här, att vara kvinna, kunna nå fram till en fri rymd där båda könen förenas i det viktigaste: att vara mänska. -

The Artist, His Admirers, His Dealers and Inheritors – Ilya Repin and His Career in the Republic of Finland

Issue No. 2/2021 The Artist, his Admirers, his Dealers and Inheritors – Ilya Repin and his Career in the Republic of Finland Timo Huusko, Ph.Lic., Chief Curator, Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum This is a revised and extended version of Timo Huusko’s article ‘Ilya Repin’s early art exhibitions in Finland’, published in Anne-Maria Pennonen (ed.), Ilya Repin. Ateneum Publications Vol. 147. Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, 2021, 103–27. Transl. Don McCracken Ilya Repin was faced with a new, unexpected situation when the October Revolution of 1917 severed the close ties between St Petersburg and Kuokkala in Finland. He had become accustomed to many changes in the course of his long life, but up until then these had been mainly due to his own decisions, especially his bold departure from Chuguev to St Petersburg to study art in 1863, then moving on to Moscow in 1877 and exhibiting with the non-academic Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) group. Repin returned to St Petersburg in 1882, and in 1892 he became first a teacher at the Imperial Academy of Arts, and later its Director. He also acquired a place in the countryside near Vitebsk in Zdrawneva, Belarus, in 1892, and subsequently entered into a relationship with Natalia Nordmann, with whom he purchased a house in Kuokkala on the Karelian Isthmus in 1899. In 1903, he moved permanently to Kuokkala and Ilya Repin, Double Portrait of Natalia Nordmann and Ilya Repin, 1903, oil on canvas, 78.5cm x 130cm Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Jenny Nurminen 2 The Artist, his Admirers, his Dealers and Inheritors – Ilya Repin and his Career in the Republic of Finland // Timo Huusko --- FNG Research Issue No.