Scandinavian Review Independent Visions Spring—2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War Two

World War Two Library of Congress: After the day of Infamy After the Day of Infamy: "Man-on-the-Street" Interviews Following the Attack on Pearl Harbour presents approximately twelve hours of opinions recorded in the days and months following the bombing of Pearl Harbour from more than two hundred individuals in cities and towns across the United States. Royal Air Force History section contains pictures and documents on the Royal Air Force from 1918 to 2010. Database includes sources on the Berlin airlift and the Battle of Britain. The Canadian Letters & Image Project: WWII – Canadian War Museum This collection contains all materials relating to Canadian from 1939 to 1945. Some individual collections may contain materials beyond this time frame. External links in collection descriptions are to casualty and burial information at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum This collection focuses on The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. It includes documents totalling almost 600 pages, covering the years 1945-1964. Supporting materials include an online version of "Truman and the Bomb: A Documentary History," edited by Robert H. Ferrell. Democracy at War: Canadian Newspapers and the Second World War During the Second World War, the staff of the century-old Hamilton Spectator newspaper kept its own monumental record of the war. This collection of more than 144,000 newspaper articles, manually clipped, stamped with the date, and arranged by subject, includes news stories and editorials from newspapers, mostly Canadian, documenting every aspect of the war. Dutch East Indies Camp Drawings Some inmates kept in diaries record of daily life in the camps, others laid down their memories into memoirs. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited Stenius, Henrik; Österberg, Mirja; Östling, Johan 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stenius, H., Österberg, M., & Östling, J. (Eds.) (2011). Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 nordic narratives of the second world war Nordic Narratives of the Second World War National Historiographies Revisited Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.) nordic academic press Nordic Academic Press P.O. Box 1206 SE-221 05 Lund, Sweden [email protected] www.nordicacademicpress.com © Nordic Academic Press and the authors 2011 Typesetting: Frederic Täckström www.sbmolle.com Cover: Jacob Wiberg Cover image: Scene from the Danish movie Flammen & Citronen, 2008. -

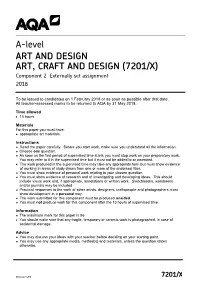

ART, CRAFT and DESIGN (7201/X) Component 2 Externally Set Assignment 2018

A-level ART AND DESIGN ART, CRAFT AND DESIGN (7201/X) Component 2 Externally set assignment 2018 To be issued to candidates on 1 February 2018 or as soon as possible after that date. All teacher-assessed marks to be returned to AQA by 31 May 2018. Time allowed • 15 hours Materials For this paper you must have: appropriate art materials. Instructions Read the paper carefully. Before you start work, make sure you understand all the information. Choose one question. As soon as the first period of supervised time starts you must stop work on your preparatory work. You may refer to it in the supervised time but it must not be added to or amended. • The work produced in the supervised time may take any appropriate form but must show evidence of working in areas of study drawn from one or more of the endorsed titles. You must show evidence of personal work relating to your chosen question. You must show evidence of research and of investigating and developing ideas. This should include visual work and, if appropriate, annotations or written work. Sketchbooks, workbooks and/or journals may be included. Practical responses to the work of other artists, designers, craftspeople and photographers must show development in a personal way. The work submitted for this component must be produced unaided. You must not produce work for this component after the 15 hours of supervised time. Information The maximum mark for this paper is 96. • You should make sure that any fragile, temporary or ceramic work is photographed, in case of accidental damage. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin

The Compass Volume 1 Issue 4 Volume 1, Issue 4, The Compass Article 3 January 2017 Redefining the Gaze: The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin Megan D'Avella Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/thecompass Recommended Citation Megan D'Avella (2017) "Redefining the Gaze: The Self Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin," The Compass: Vol. 1 : Iss. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/thecompass/vol1/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@Arcadia. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Compass by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@Arcadia. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Redefining the Gaze: The Self-Portraiture of Helene Schjerfbeck, Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin By Megan D’Avella, Arcadia University Introduction manner, males boldly presented themselves through self-imagery.1 This can make early Throughout the history of art, self-portrai- female self-portraiture difficult to read autobi- ture has been explored by artists as means ographically, as a subdued painting does not to emphasize their artistic capabilities, claim necessarily translate into a subdued woman. their importance in modern art, and solidify Keeping in mind the traditional stan- their existence. The work accomplished by dard of female portraiture, the un-idealized female artists, however, must be considered self-representations that Helen Schjerfbeck, separately from the overall genre of portrai- Romaine Brooks, and Marianne Werefkin ture. Women in the early twentieth century painted were no small statement at the turn of needed to approach the canvas with careful the century. -

Finnish Narratives of the Horse in World War II 123

Finnish Narratives of the Horse in World War II 123 FINNISH NARRATIVES OF THE HORSE IN WORLD WAR II Riitta-Marja Leinonen Introduction There were millions of horses involved in World War II, most of them in supply and transport service or in the field artillery. The time of cavalries was passing and only Germany and the Soviet Union had large cavalry forces.1 Finland had only one cavalry brigade in World War II and it was incorporated into the infantry in battle situations.2 Nevertheless, the role of the horse was crucial for Finland, especially in the Winter War3 when most army transportation was conducted using horses. Horses were ideal for transportation use in the roadless terrain of the boreal forests in the borderlands of Finland and the Soviet Union. The World War II means three wars to Finns: the Winter War (November 1939 to March 1940), the Continuation War (June 1941 to September 1944) and the Lapland War (September 1944 to April 1945). The underlying cause of the Winter War was Soviet concern about Nazi Germanyʼs expansionism. The secret protocol of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of August 1939 gave the Soviet Union influence over Finland, the Baltic states, and parts of Eastern Europe. The Winter War started when Soviet troops invaded Finland, and it ended 105 days later in the Moscow treaty where Finland lost 11% of its surface area and its second largest city, Viipuri. The Interim peace lasted for fifteen months. During that time Finland was trying to find an ally and finally made an agreement with Germany hoping to get the lost land areas back. -

Mo Birget Soađis (How to Cope with War) – Strategies of Sámi Resilience During the German Influence

Mo birget soađis (How to cope with war) – strategies of Sámi resilience during the German influence Adaptation and resistance in Sámi relations to Germans in wartime Sápmi, Norway and Finland 1940-1944 Abstract The article studies the Sámi experiences during the “German era” in Norway and Finland, 1940-44, before the Lapland War. The Germans ruled as occupiers in Norway, but had no jurisdiction over the civilians in Finland, their brothers-in-arms. In general, however, encounters between the local people and the Germans appear to have been cordial in both countries. Concerning the role of racial ideology, it seems that the Norwegian Nazis had more negative opinions of the Sámi than the occupiers, while in Finland the racial issues were not discussed. The German forces demonstrated respect for the reindeer herders as communicators of important knowledge concerning survival in the arctic. The herders also possessed valuable meat reserves. Contrary to this, other Sámi groups, such as the Sea Sámi in Norway, were ignored by the Germans resulting in a forceful exploitation of sea fishing. Through the North Sámi concept birget (coping with) we analyse how the Sámi both resisted and adapted to the situation. The cross-border area of Norway and Sweden is described in the article as an exceptional arena for transnational reindeer herding, but also for the resistance movement between an occupied and a neutral state. Keyword: Sámi, WWII, Norway and Finland, reindeer husbandry, local meetings, Birget Sámi in different wartime contexts In 1940 the German forces occupied Norway. Next year, as brothers-in-arms, they got northern Finland under their military command in order to attack Soviet Union. -

Travelling in a Palimpsest

MARIE-SOFIE LUNDSTRÖM Travelling in a Palimpsest FINNISH NINETEENTH-CENTURY PAINTERS’ ENCOUNTERS WITH SPANISH ART AND CULTURE TURKU 2007 Cover illustration: El Vito: Andalusian Dance, June 1881, drawing in pencil by Albert Edelfelt ISBN 978-952-12-1869-9 (digital version) ISBN 978-952-12-1868-2 (printed version) Painosalama Oy Turku 2007 Pre-print of a forthcoming publication with the same title, to be published by the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, Humaniora, vol. 343, Helsinki 2007 ISBN 978-951-41-1010-8 CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. 5 INTRODUCTION . 11 Encountering Spanish Art and Culture: Nineteenth-Century Espagnolisme and Finland. 13 Methodological Issues . 14 On the Disposition . 17 Research Tools . 19 Theoretical Framework: Imagining, Experiencing ad Remembering Spain. 22 Painter-Tourists Staging Authenticity. 24 Memories of Experiences: The Souvenir. 28 Romanticism Against the Tide of Modernity. 31 Sources. 33 Review of the Research Literature. 37 1 THE LURE OF SPAIN. 43 1.1 “There is no such thing as the Pyrenees any more”. 47 1.1.1 Scholarly Sojourns and Romantic Travelling: Early Journeys to Spain. 48 1.1.2 Travelling in and from the Periphery: Finnish Voyagers . 55 2 “LES DIEUX ET LES DEMI-DIEUX DE LA PEINTURE” . 59 2.1 The Spell of Murillo: The Early Copies . 62 2.2 From Murillo to Velázquez: Tracing a Paradigm Shift in the 1860s . 73 3 ADOLF VON BECKER AND THE MANIÈRE ESPAGNOLE. 85 3.1 The Parisian Apprenticeship: Copied Spanishness . 96 3.2 Looking at WONDERS: Becker at the Prado. 102 3.3 Costumbrista Painting or Manière Espagnole? . -

LANDSCAPES of LOSS and DESTRUCTION Sámi Elders’ Childhood Memories of the Second World War

LANDSCAPES OF LOSS AND DESTRUCTION Sámi Elders’ Childhood Memories of the Second World War Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto, University of Jyväskylä Oula Seitsonen, University of Helsinki The so-called Lapland War between Finland and Germany at the end of the Second World War led to a mass-scale destruction of Lapland. Both local Finnish residents and the indigenous Sámi groups lost their homes, and their livelihoods suffered in many ways. The narratives of these deeply traumatic experiences have long been neglected and suppressed in Finland and have been studied only recently by academics and acknowledged in public. In this text, we analyze the interviews with four elders of one Sámi village, Vuotso. We explore their memories, from a child’s perspective, scrutinizing the narration as a multilayered affective process that involves sensual and embodied dimensions of memory.1 Keywords: Second World War, Sámi, post-colonialism, memory, Lapland Introduction in 1944, due to the so-called Lapland War, a conflict Linguistically, “loss” suggests absence, but this between Finland and the former ally, Nazi Germany. loss of home and community has an ongoing Most Laplanders were eventually able to return to emotional presence. (Field 2008: 115) their home villages, but, in most cases, there were no homes left. Lapland, its villages, dwellings and in- Losing one’s home is a deeply traumatic experience frastructure had suffered massive destruction by the for all family members, including children. During German army, which, while retreating to northern the Second World War (henceforth WWII), hun- Norway, applied “scorched earth tactics”.2 The dreds of thousands of European families left their German troops also booby-trapped the smoking ru- homes due to mass evacuations of civilians. -

FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL and BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O

JOURNAL OF INNISH TUDIES F S Volume 19 Number 1 June 2016 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-937875-94-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University; hilary.virtanen@finlandia. edu Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Titus Hjelm, Reader, University College London Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of Finnish Literature, University of Helsinki Juha -

“Ghosts in the Background” and “The Price of the War” Representations of the Lapland War in Finnish Museums

Nordisk Museologi 2016 • 2, s. 60–77 “Ghosts in the background” and “The price of the war” Representations of the Lapland War in Finnish museums Suzie Thomas & Eerika Koskinen-Koivisto Abstract: Museums decide which events and perspectives to privilege over others in their exhibitions. In the context of “difficult” or “dark” histories – in which the subject matter might be painful, controversial or in some other way challenging for one or more community or interest groups to reconcile with – some events may be marginalized or ignored. This may also happen due to official narratives diverting attention to other events that have come to be seen as more “important” or worthy of discussion. We explore the ways that information about the Lapland War (1944–1945) is incorporated into permanent exhibitions at five Finnish museums: the Provincial Museum of Lapland; Siida – the National Museum of the Finnish Sámi; the Gold Prospector Museum; the Military Museum of Finland; and the Finnish Airforce Museum. Despite the significant social and environmental upheavals brought about by the brief but destructive conflict, it seems surprisingly rarely addressed.1 Keywords: Dark heritage, dark tourism, difficult histories, exhibition analysis, Second World War, Lapland War, Sámi heritage, military history. Over the past few decades, interest has immaterial legacies of the Second World War, noticeably increased in “dark” or “difficult” how visitors experience them, and the strategies history, heritage and tourism. This has impacted employed to commemorate, preserve or curate academic research, in which we have seen sites connected to this conflict heritage (e.g. areas of study emerge such as “dark tourism” Moshenska 2015).