Proceeding Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

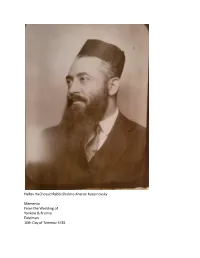

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

301 Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon By: ZVI RON In this article we investigate the origin and development of saying vari- ous Psalms and selected verses from Psalms before Birkat Ha-Mazon. In particular, we will attempt to explain the practice of some Ashkenazic Jews to add Psalms 145:21, 115:18, 118:1 and 106:2 after Ps. 126 (Shir Ha-Ma‘alot) and before Birkat Ha-Mazon. Psalms 137 and 126 Before Birkat Ha-Mazon The earliest source for reciting Ps. 137 (Al Naharot Bavel) before Birkat Ha-Mazon is found in the list of practices of the Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero (1522–1570). There are different versions of this list, but all versions include the practice of saying Al Naharot Bavel.1 Some versions specifically note that this is to recall the destruction of the Temple,2 some versions state that the Psalm is supposed to be said at the meal, though not specifically right before Birkat Ha-Mazon,3 and some versions state that the Psalm is only said on weekdays, though no alternative Psalm is offered for Shabbat and holidays.4 Although the ex- act provenance of this list is not clear, the parts of it referring to the recitation of Ps. 137 were already popularized by 1577.5 The mystical work Seder Ha-Yom by the 16th century Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe ben Machir was first published in 1599. He also mentions say- ing Al Naharot Bavel at a meal in order to recall the destruction of the 1 Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalah in Liturgy, Halakhah and Customs (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2000), pp. -

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner A Student's Guide and Preparation for Observant Jews ♦California State University, Monterey Bay♦ 1 Contents Introduction 1 Chp. 1, Kiddush/Hillul Hashem 9 Chp. 2, Torah Study 28 Chp. 3, Kashrut 50 Chp. 4, Shabbat 66 Chp. 5, Sexual Relations 87 Chp. 6, Social Relations 126 Conclusion 169 2 Introduction Today, all Jews have the option to pursue a college education. However, because most elite schools were initially directed towards training for the Christian ministry, nearly all American colonial universities were off limits to Jews. So badly did Jews ache for the opportunity to get themselves into academia, that some actually converted to Christianity to gain acceptance.1 This began to change toward the end of the colonial period, when Benjamin Franklin introduced non-theological subjects to the university. In 1770, Brown University officially opened its doors to Jews, finally granting equal access to a higher education for American Jews.2 By the early 1920's Jewish representation at the leading American universities had grown remarkably. For example, Jews made up 22% of the incoming class at Harvard in 1922, while in 1909 they had been only 6%.3 This came at a time when there were only 3.5 millions Jews4 in a United States of 106.5 million people.5 This made the United States only about 3% Jewish, rendering Jews greatly over-represented in universities all over the country. However, in due course the momentum reversed. During the “Roaring 1920’s,” a trend towards quotas limiting Jewish students became prevalent. Following the lead of Harvard, over seven hundred liberal arts colleges initiated strict quotas, denying Jewish enrollment.6 At Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons for instance, Jewish enrollment dropped from 50% in 1 Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1959), 557. -

The Month of Elul Is the Last Month of the Jewish Civil Year

The Jewish Month of Elul A Month of Mercy and Forgiveness Hodesh haRahamin vehaSelihot The month of Elul is the last month of the Jewish civil year. However, according to the biblical Calendar, it is also the sixth month, counting from Nisan which is called the “first of the months” in the Torah (Ex. 12:2). This document explores the spirituality of Elul for Jews and Judaism. Etz Hayim—“Tree of Life” Publishing “It is a Tree of Life to all who hold fast to It” (Prov. 3:18) The Month of Elul The month of Elul1 is the last month of the Jewish civil year. However, according to the biblical Calendar, it is also the sixth month, counting from Nisan which is called the “first of the months” in the Torah (Ex. 12:2). Elul precedes the month of Tishrei (called the seventh month, Numbers 29:1). Placed as the last of the months and followed by the New Year, Elul invites an introspective reflection on the year that has been. Elul begins the important liturgical season of Return and Repentance which culminates with Rosh HaShanah,2 the Days of Awe3 and Yom Kippur4 (1-10 Tishrei). Elul takes its place as an important preparation time for repentance. Elul follows the months of Tammuz and Av, both catastrophic months for Israel according to tradition. Tammuz is remembered as the month in which the people of Israel built the Golden Calf (Ex. 32) and Av, the month of the sin of the spies (Num. 13). The proximity of Tammuz and Av to Elul underscores the penitential mode of this, the last of the months, before the new beginning and spiritual re-creation that is precipitated with the New Year beginning the following month of Tishrei. -

The Morning Prayers the Prayers and Blessings to Be Said Daily Upon Awakening, for Both Weekdays and Shabbat

בס""" "דד תפלת השחר The Morning Prayers The prayers and blessings to be said daily upon awakening, for both weekdays and Shabbat Comparable to the Siddur Tehillat H ASHEM NUSACH HA,A RI ZAL According to the Text of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Compiled and newly typeset by Shmuel Gonzales. The text is comparable with the text of the Siddur Tehillat Hashem . It is provided via the Internet as a resource for study and for use for prayer when a Siddur is not immediately available. This text was created with the many people in mind that travel through out the world and find, to their horror, that their Siddur is missing. Now it’s accessible for all of us in those emergency situations. One should not rely only upon this text. A Siddur is not just an order of prayer. It is intended to serve as a text for education in Jewish tradition and the keeping of mitzvot. This text lacks many of those qualities. Thus, one should own a Siddur of their own and study it. When printed this text is “sheymish”, or bearing the Divine Name. On paper it is fit for sacred use and therefore should not be disposed of or destroyed. If you print it, when you are finished it should be taken to a local Orthodox synagogue so that it may be buried in honor, according to Jewish Law. Version 3.2 C November 2010 - 1 - ✶✶✶ ברכות השח ר ✶ Morning Blessings Upon awakening, before saying any other words or arising from bed, one is obligated to first acknowledge God as King, worthy of our gratitude: מLֶדמLֶד ה ה ֲאִני ְלָפֶניך ֶמֶלך ַ חי ְוַקָיּם, ֶשֶׁהֱחַזְרָתּ ִבּי ִנְשָׁמִתי ְבֶּחְמָל ה. -

706 Beis Moshiach

706:Beis Moshiach 03/08/2009 9:43 AM Page 3 contents IN THE ERA OF THE HEELS OF 4 MOSHIACH D’var Malchus | Sichos in English REB LEVI YITZCHOK’S VICTORY 6 Shlichus | Chani Nussbaum THE REBBE’S WAR FOR CROWN 10 HEIGHTS Feature | Avrohom Ber THE ART OF STORYTELLING 18 Inisght | Ofra Bedosa RABBI YITZCHOK ISAAC HERZOG Z”L USA 24 Feature | Gershon Nof 744 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Tel: (718) 778-8000 Fax: (718) 778-0800 [email protected] SOUL CONNECTION WITH RABBI LEVI www.beismoshiach.org 30 YITZCHOK Z”L EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: 20 Av | Nosson Avrohom M.M. Hendel ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur CHASSIDIC ADVENTURES IN SOVIET [email protected] 34 RUSSIA HEBREW EDITOR: Memoirs of R’ Hillel Zaltzman | Avrohom Rainitz Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan [email protected] Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish holidays (only once in April and October) for $160.00 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and in all other places for $180.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2009 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. 706:Beis Moshiach 03/08/2009 9:43 AM Page 4 dvar malchus IN THE ERA OF THE HEELS OF MOSHIACH Sichos In English (Adapted from Likkutei Sichos, Vol. IX, p. 71ff, Sefer HaSichos 5749, p. -

WE WANT MOSHIACH NOW! MOSHIACH WE WANT Nanna Rosengård: Messiah.”

“When the Rebbe was alive, just about every Lubavitcher (---) was confident that he was the Nanna Rosengård: WE WANT MOSHIACH NOW! MOSHIACH WE WANT Nanna Rosengård: Messiah.” Is this sort of a belief a new phenomenon in the Chabad-Lubavitch movement or is there more to the story? Chabad-Lubavitch is a Jewish movement that has become well known both for its active outreach campaigns, bringing life to Jewish communites around the world, and their expectant belief in the Messiah. This belief is often WE WANT associated with Rabbi Schneerson, who MOSHIACH is said to be the Messiah by some NOW! Lubavitchers, and by scholars to have created a messianic fervor among his Understanding the adherents. The thesis at hand pinpoints Messianic Message the most important messianic beliefs put in the Jewish forward by the last two generations of Chabad-Lubavitch leaders in Chabad-Lubavitch, relating Movement them back to the first generations of the movement in the 1700s. Åbo Akademi University Press ISBN 978-951-765-514-9 Nanna Rosengård 2009 Photo: Ville Kavilo Ville Photo: Nanna Rosengård, was born 1978 in Stockholm, Sweden and grew up in Dagsmark, Kristinestad in Finland. She received a Masters of Theology from Åbo Akademi University 2005 and enrolled in the doctoral program of Jewish Studies the following year. Photo on front page taken by Nanna Rosengård in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York 2006. Design: Laura Karanko Åbo Akademi University Press Biskopsgatan 13, FIN-20500 ÅBO, Finland Tel. +258-20 786 1468 Fax +358-20 786 1459 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.abo.fi/stiftelsen/forlag Distribution: Oy Tibo-Trading Ab P.O.Box 33, FIN-21601 PARGAS, Finland Tel. -

Likkutei Sichos the Announcement of the Redemption

IN LOVING MEMORY OF A DEAR FREIND Reb Yosef Yisroel ben Reb Sholom vWg Rosner Passed away on 7 Menachem-Av, 5777 /v /c /m /b /, yhiee`aeil Ð miciqgd xve` Ð 'ixtq * ________________________________________________ DEDICATED BY HIS FRIENDS Mr. & Mrs. Gershon and Leah uhjha Wolf Rabbi & Mrs. Yosef Y. and Gittel Rochel uhjha Shagalov LIKKUTEI * * * IN LOVING MEMORY OF OUR DEAR FATHER zegiy ihewl Reb Kalman ben Reb Menachem Mendel vWg Rubin SICHOS Passed away on 23 Nissan, 5764 zyecw ceakn /v /c /m /b /, AN lcprnANTHOLOGY mgpn x"enc` OF TALKS AND IN HONOR OF OUR DEAR MOTHER od`qxe`ipy מליובאוויטש Mrs. Elisheva (Elly) bas Rina whj,a Rubin May she go from strength to strength byb the in health, happiness, Torah and mitzvot. Lubavitcher Rebbe * Rabbi Menachemjzelrdaglya M. Schneerson DEDICATED BY THEIR CHILDREN uhjha `kbk wlg wlg zegiy zegiy ihewl ihewl ly ly zegiyd zegiyd itl itl caerne caerne mbxezn mbxezn (iytg mebxz) 5HSULQWHGIRUWKH6HYHQWK'D\RI3HVDFK vhw au,; cvpm, gbhbh "nahj udtukv"!!! "nahj gbhbh cvpm, au,; vhw 9RO30 kvesau, ukpryho buxpho: buxpho: ukpryho kvesau, yk/: 4486-357 )817( tu 5907-439 )323( 5907-439 tu )817( 4486-357 yk/: C LQIR#WRUDKEOLQGRUJ thnhhk: ici lr xe`l `vei %H$3DUWQHU iciC lr xe`l `vei ,Q6SUHDGLQJInyonei Moshiach U'geula "wgvi iel oekn 7R'HGLFDWH7KLV3XEOLFDWLRQ "wgvi iel oekn" 'a c"ag xtk " ,Q+RQRU2I<RXU)DPLO\2U$/RYHG2QHV 'a c"ag xtk )RU0RUH,QIR&DOO RU RUHPDLOLQIR#WRUDKEOLQGRUJ שנת שנת חמשת חמשת אלפי אלפי שבע שבע מאות מאות שישי ושבעי ותשע לבריאהלבריאה שנת חמשת אלפי שבע מאות ושבעי לבריאה giynd jln x"enc` w"k ze`iypl -

Nova Law Review

Nova Law Review Volume 19, Issue 3 1995 Article 5 Halacha as a Model for American Penal Practice: A Comparison of Halachic and American Punishment Methods Kenneth Shuster∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Halacha as a Model for American Penal Practice: A Comparison of Halachic and American Punishment Methods Kenneth Shuster Abstract America’s punishment system is not working.2 In the United States, in 1991 alone, a murder was committed every twenty-one minutes, a woman was raped every five minutes, a person was robbed every forty-six seconds, and a burglary occurred every ten seconds KEYWORDS: penal, American, Halachic Shuster: Halacha as a Model for American Penal Practice: A Comparison of H Halacha as a Model for American Penal Practice: A Comparison of Halachic and American Punishment Methods Kenneth Shuster" TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 965 II. HALACHIC PUNISHMENT ........................ 971 A. CapitalPunishment ........................ 971 B. Indentured Servitude ....................... 978 C. CorporalPunishment ....................... 981 D. Excommunication ......................... 983 IL. AMERICAN LAW. .............................. 986 A. CapitalPunishment ........................ 986 B. Indentured Servitude ....................... 993 C. CorporalPunishment ....................... 997 D. Excommunication ........................ 1001 IV. OTHER ARGUMENTS AGAINST PENAL SERVITUDE AND SHAMING ................................ 1007 A. Prison Servitude ....................... 1007 B. Sign and Advertisement Shaming Sanctions .... 1010 V. CONCLUSION ............................. 1011 I. INTRODUCTION It is with the unfortunate, above all, that humane conduct is necessary.' * Bachelor of Religious Education (B.R.E.), Talmudic University of Florida, 1983; M.S., Bernard Revel Graduate School, Yeshiva University, 1988; J.D., New York Law School, 1993; LL.M., New York University Law School, 1994. -

Temple Beth Or Library

Temple Beth Or Library Item Listing by Author All Author(s) Title : Subtitle (Series) Call#1 Call#2 Call#3 Aaron, David Endless Light : The Ancient Path of Kabbalah 150 Aar Aaron, David Seeing God : ten life-changing lessons of the Kabbalah 162.3 Aar Abe, Masao / Borowitz, Buddhist-Jewish Dialogue 661 Abe Eugene B. Abraham, Michelle Shapiro Good Night (Lilah Tov) Abr Abraham, Michelle Shapiro My Cousin Tamar Lives in Israel Abr Abraham, Pearl Romance Reader 560 Abr Abramovitsh, S.Y. / Miron, Tales of Mendele the Book Peddler : Fishke the Lame and Benjamin 190 Abr Dan. / Frieden, Ken , 1955 the Third (Library of Yiddish classics) Abramowitz, Yosef / Jewish Family and Life : traditions, holidays, and values for today's T 220 Abr Silverman, Susan parents and children Abrams, Judith Z. Rosh Hashanah (A Family Service) Abr Abrams, Judith Z. The Talmud for Beginners : Prayer (Volume 1) 102.1 Abr Abramson, Glenda, ed. Oxford Book of Hebrew Short Stories 550.3 Oxf Ackerman, Diane Zookeeper's Wife : A War Story 738.30 ZAB Ack 9 Address, Richard and That You May Live Long: Caring for Our Aging Parents, Caring for 653 Add Person, Hara / Address, Ri Ourselves : Caring for Our Aging Parents, Caring for Ourselves Address, Richard F. time to prepare, A : a practical guide for individuals and families in 222.5 Add determining one's wishes for extraordinary medical treatment and fi Address, Richard F. / To Honor and Respect : A Program and Resource Guide for 653 Add Rosenkranz, Andrew L. Congregations on Sacred Aging Adelman, Peninah J Girl's Guide YA 619.9 Ade Adelson, Leone Mystery Bear: A Purim Story Ade Adelson, Leone , 1908- / mystery bear, The : a Purim story J 249.5 Ade Howland, Naomi , ill. -

The-Divine-Code-Bibliography

1 BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR THE DIVINE CODE B”H (.is usually spelled ch כ ,ח R. is the abbreviation for Rabbi. Phonetic ĥ for) Ahavat Ĥesed. By R. Yisrael Meir (HaKohen) Kagan of Radin (1838-1933). Aĥiezer. Responsa by R. Ĥayim Ozer Gradzinski of Vilna, Lithuania (1863-1940). Ari (AriZal). Pseudonym of R. Yitzĥak Luria of Tzefat, Israel (1534-1572), the most renowned Kabbalist Rabbi, and an important teacher of Torah-law rulings. Aruĥ. Dictionary of Talmud terms by R. Natan ben Yeĥiel of Rome (c. 1045-1103). Aruĥ HaShulĥan. Code of Torah Law by R. Yeĥiel Miĥel HaLevi Epstein, Rabbi of Novardok, Russia (1829-1908). It follows the sequence of the Shulĥan Aruĥ. Aruĥ Le’Nair. Analyses on Talmud, by R. Yaacov Etlinger, Germany (1798-1871). Auerbach, R. Ĥayim Yehuda. One of the founders and first Head of Yeshivas Sha’arei Shamayim, Jerusalem, Israel (1883-1954). Avnei Neizer. Responsa by R. Avraham Borenstein of Poland (1839-1910). Avot D’Rabbi Natan. Chapters of ethics, compiled by Rabbi Natan (2nd century). Baal Halaĥot Gedolot. One of the earliest Codes of Torah Law, by R. Shimon Kayyara, who is believed to have lived in Babylonia in the ninth century, and to have studied under the Geonim Rabbis of the Academy in Sura, Babylon. Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli). Talmud composed by the Sages in Babylonia (present day Iraq) in the second to the fifth centuries, completed 450-500. Baĥ. Acronym for Bayit Ĥadash, a work of Torah Law by R. Yoel Sirkis of Cracow, Poland (c. 1561-1640). Bedek HaBayit. Additions to Beit Yosef by R. -

Michael Strassfeld Papers Ms

Michael Strassfeld papers Ms. Coll. 1218 Finding aid prepared by John F. Anderies; Hebrew music listed by David Kalish and Louis Meiselman. Last updated on May 15, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2016 December 14 Michael Strassfeld papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Series I. Education.................................................................................................................................10 Series