Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

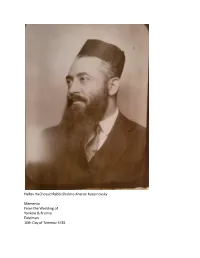

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

Fundamentals of Judaism

Fundamentals of Judaism Selections from the works of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and outstanding Torah-true thinkers I Edited by JACOB BREUER Published for THE RABBI SAMSON RAPHAEL HIRSCH SOCIETY by Philipp Feldheim, Publisher New York CHAPTER EIGHT l' l' l' PROBLEMS OF THE DIASPORA IN THE SHULCHAN ARUCH By DR. DAVID HOFFMAN According to the Shulchan Aruch the support of a needy Jew is a law. Charity for the needy "Akkum," while considered a moral obligation, is urged on the basis of Oi'it!' ~::Ji' as a means of maintaining peaceful relations with the non-Jewish world. This qualified motivation has become the target of widespread and indignant criticism. One of the critics, the frankly prejudiced Justus, voiced his opposition as follows: "The tendency under lying these rules is to create the belief in the "Akkum" (Christ ians) that they have good friends in the Jews." This materialistic concept is pure nonsense; perhaps it is an outgrowth of wishful thinking. That it is utterly unfounded is substantiated by the oldest source of this rule, the Mishna in Gittin (59 a): "The following rules were inaugurated because of o''i~ ~::Ji': " .... the release of game, birds or fish from a trap set by another person is considered robbery; objects found by a deaf-mute, mentally deficient or minor (including Jews) must not be forcibly seized; .... impoverished heathens must nof be restrained from collecting the gleanings, forgotten sheaves and the fruit left for the poor at the edge of the this "for the sake of peace." On the basis of this Mishna it is difficult to see how any ob server can side with Justus' interpretation. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

January-February 2018

Shofar Tevet - Adar 5778 • January/February 2018 In this issue...you can click on the Rabbi’s Message page you would like to read first. Acts of Tzedakah ....................................... 32 Seeking Higher Purpose in the Biennial Impressions ...........................14-16 New Year Calendar .............................................34-35 Cantor .....................................................4-5 A new secular year has dawned, and, as with all things new, it brings the opportunity to greet it with optimism Chanukah Around the World ...................6-7 and thoughtfulness for its possibilities. College Connection ................................... 22 For some of us, the possibility exists of choosing to do something truly different with our lives in this new year. Most of us, however, Community ............................................... 19 will find ourselves carrying forward on a path that has been defined by our prior commitments to family, community, and work. Does this mean that Cultural Arts .............................................. 22 2018 must be merely a continuation of the things that defined 2017? Not Education Directors .................................. 10 necessarily. Hebrew Corner ......................................... 11 Continued on page 3 Honorable Menschen ................................. 9 Jewish LIFE ..........................................14-16 Legacy Circle ............................................... 7 Tu BiShvat Celebration Lifecycle (TBE Family News) ...................... 29 -

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

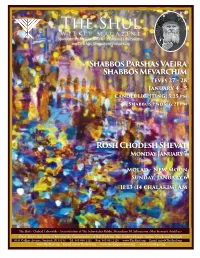

The Shul Weekly Magazine Sponsored by Mr

B”H The Shul weekly magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Parshas Vaeira Shabbos Mevarchim Teves 27 - 28 January 4 - 5 CANDLE LIGHTING: 5:25 pm Shabbos Ends: 6:21 pm Rosh Chodesh Shevat Monday January 7 Molad - New Moon Sunday, January 6 11:13 (14 chalakim) AM Te Shul - Chabad Lubavitch - An institution of Te Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson (May his merit shield us) Over Tirty fve Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.theshulpreschool.org www.cyscollege.org The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Our Teen girls go out onto the streets of 33154 before Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar Shabbos to hand out shabbos candles and encourage all A Time to Pray 5 Jewish women and girls to light. Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week Celebrating Shabbos 6-7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience Community Happenings 8 - 9 Sharing with your Shul Family 10-15 Inspiration, Insights & Ideas Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE 16- 19 Get The Picture The full scoop on all the great events around town 20 French Connection Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 21 Refexion Semanal 22 In a woman’s world Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman The Hebrew School children who are participating in a 23-24 countrywide Jewish General Knowledge competition, take Networking Effective Advertising the 2nd of 3 tests. -

Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

301 Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon By: ZVI RON In this article we investigate the origin and development of saying vari- ous Psalms and selected verses from Psalms before Birkat Ha-Mazon. In particular, we will attempt to explain the practice of some Ashkenazic Jews to add Psalms 145:21, 115:18, 118:1 and 106:2 after Ps. 126 (Shir Ha-Ma‘alot) and before Birkat Ha-Mazon. Psalms 137 and 126 Before Birkat Ha-Mazon The earliest source for reciting Ps. 137 (Al Naharot Bavel) before Birkat Ha-Mazon is found in the list of practices of the Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero (1522–1570). There are different versions of this list, but all versions include the practice of saying Al Naharot Bavel.1 Some versions specifically note that this is to recall the destruction of the Temple,2 some versions state that the Psalm is supposed to be said at the meal, though not specifically right before Birkat Ha-Mazon,3 and some versions state that the Psalm is only said on weekdays, though no alternative Psalm is offered for Shabbat and holidays.4 Although the ex- act provenance of this list is not clear, the parts of it referring to the recitation of Ps. 137 were already popularized by 1577.5 The mystical work Seder Ha-Yom by the 16th century Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe ben Machir was first published in 1599. He also mentions say- ing Al Naharot Bavel at a meal in order to recall the destruction of the 1 Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalah in Liturgy, Halakhah and Customs (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2000), pp. -

June-July 2018 | Sivan/Tammuz 5778 | Vol

June-July 2018 | Sivan/Tammuz 5778 | Vol. 44 No. 9 Take a walk. Say a prayer. Find your space. PAGES 8-9 Kleinman Pecan Grove Re-energize and refocus with a peaceful walk through our beautiful pecan grove located along Northwest Highway. CINEMA EMANU-EL 2018 P. 14 CLERGY MESSAGE Making a Splash, ly Herzo er g C b o im h e K n i Jewishly b b a R ’ve always been drawn to water. domestic abuse, a painful divorce, a complicated surgery, a I grew up by the Pacific Ocean tragic loss. And the mikvah continues to be one way to mark and loved early morning the gratitude and responsibility of becoming a parent, to drives along Route 1 when the prepare for an upcoming wedding or to start any exciting waterI was calm, a mix of purples and new life chapter. blues. I love hikes along creeks that lead to I often marvel at the “glow” that radiates from people a glistening pond or lake. I treasure the delicious moments after they immerse. I believe that glow emerges from a sense of bathing my kiddos, which has now become more like an of renewed hope, embedded in the word itself which shares effort to keep the tidal waves of splashes from crashing over the same root with the Hebrew word for hope (tikvah). As we onto the bathroom floor. sense our strength and our vulnerability in the face of life’s I have also been frightened by water, its power and might. joys and challenges, the waters hold us in the hope of God’s Our home was nestled in the mountains which dramatically presence as we make our way forward. -

Sanctity As Defined by the Silent Prayer Benjamin Blech Sanctity Isn't

145 Sanctity as Defined by the Silent Prayer Sanctity as Defined by the Silent Prayer Benjamin Blech Sanctity isn’t meant to be an esoteric subject reserved solely for rabbis, theologians, and scholars. It is a theme that has been accorded a blessing that is to be recited by every Jew three times a day as part of the Amidah, the Silent Prayer composed by the Men of the Great Assembly, in order to give voice to our collective desire to communicate with the Almighty. The Amidah is the paradigm of prayer. It is what the Talmud and rabbinic commentators refer to as “[the] t’fillah.” It is the one prayer at whose beginning and ending we take three steps backward followed by three steps forward, indicating our awareness of entering and then subsequently leaving the presence of the supreme Sovereign. The wording and structure of this prayer are profoundly significant. Its text carries the spiritual weight of authorship by saintly scholars imbued with prophetic inspiration. All this is by way of introducing the reader to the importance (as well as the practical relevance) of the insights of the Amidah regarding the theme of holiness. It is within the context of the words chosen for our daily conversations with God that we will discover how the concept of sanctity helps us resolve two of the most pressing problems of life: How can we be certain that God exists? And if indeed there is a God, what does that mean for our mission here on earth? 146 Benjamin Blech Can We Ever Prove God’s Existence? Philosophers throughout the ages have debated this issue without coming to a universally agreed-upon resolution. -

Orthodoxy in American Jewish Life1

ORTHODOXY IN AMERICAN JEWISH LIFE1 by CHARLES S. LIEBMAN INTRODUCTION • DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF ORTHODOXY • EARLY ORTHODOX COMMUNITY • UNCOMMITTED ORTHODOX • COM- MITTED ORTHODOX • MODERN ORTHODOX • SECTARIANS • LEAD- ERSHIP • DIRECTIONS AND TENDENCIES • APPENDLX: YESHIVOT PROVIDING INTENSIVE TALMUDIC STUDY A HIS ESSAY is an effort to describe the communal aspects and institutional forms of Orthodox Judaism in the United States. For the most part, it ignores the doctrines, faith, and practices of Orthodox Jews, and barely touches upon synagogue hie, which is the most meaningful expression of American Orthodoxy. It is hoped that the reader will find here some appreciation of the vitality of American Orthodoxy. Earlier predictions of the demise of 11 am indebted to many people who assisted me in making this essay possible. More than 40, active in a variety of Orthodox organizations, gave freely of their time for extended discussions and interviews and many lay leaders and rabbis throughout the United States responded to a mail questionnaire. A number of people read a draft of this paper. I would be remiss if I did not mention a few by name, at the same time exonerating them of any responsibility for errors of fact or for my own judgments and interpretations. The section on modern Orthodoxy was read by Rabbi Emanuel Rackman. The sections beginning with the sectarian Orthodox to the conclusion of the paper were read by Rabbi Nathan Bulman. Criticism and comments on the entire paper were forthcoming from Rabbi Aaron Lichtenstein, Dr. Marshall Ski are, and Victor Geller, without whose assistance the section on the number of Orthodox Jews could not have been written. -

Rabbi Eliezer Levin, ?"YT: Mussar Personified RABBI YOSEF C

il1lj:' .N1'lN1N1' invites you to join us in paying tribute to the memory of ,,,.. SAMUEL AND RENEE REICHMANN n·y Through their renowned benevolence and generosity they have nobly benefited the Torah community at large and have strengthened and sustained Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah here in Toronto. Their legendary accomplishments have earned the respect and gratitude of all those whose lives they have touched. Special Honorees Rabbi Menachem Adler Mr. & Mrs. Menachem Wagner AVODASHAKODfSHAWARD MESORES A VOS AW ARD RESERVE YOUR AD IN OUR TRIBUTE DINNER JOURNAL Tribute Dinner to be held June 3, 1992 Diamond Page $50,000 Platinum Page $36, 000 Gold Page $25,000 Silver Page $18,000 Bronze Page $10,000 Parchment $ 5,000 Tribute Page $3,600 Half Page $500 Memoriam Page '$2,500 Quarter Page $250 Chai Page $1,800 Greeting $180 Full Page $1,000 Advertising Deadline is May 1. 1992 Mall or fax ad copy to: REICHMANN ENDOWMENT FUND FOR YYH 77 Glen Rush Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario M5N 2T8 (416) 787-1101 or Fax (416) 787-9044 GRATITUDE TO THE PAST + CONFIDENCE IN THE FUTURE THEIEWISH ()BSERVER THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021 -6615 is published monthly except July and August by theAgudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid in New York, N.Y. LESSONS IN AN ERA OF RAPID CHANGE Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $1 O.00 6 surcharge per year. -

Spring 2004 Template

Society THE VANISHING AMERICAN JEW By Berel Wein The recent population study of born to Jewish parents and claimed has been a feature of American Jewry American Jewry by The Graduate Judaism as their religion. By 2001 that since 1970.” The children of such mar- Center of The City University of New number had shrunk to 2,760,000. In riages are in the main being raised out- York, published in 2001 (and repub- 1990 there were 813,000 people born side of Judaism—in any of its forms. lished in 2003 by The Center For to Jewish parents but claimed no reli- The rates for intermarriage were Cultural Judaism), reveals one glaring gion as their own. In 2001 that num- reported at 52 percent in 2001, no real fact behind all of the graphs, technical ber had risen to 1,120,000. The study change from 51 percent in 1990. language and statistical weights— also shows that there are approximate- What this demographic disaster may American Jewry is shrinking, American Jewry is shrinking, and at a ly 2,300,000 people who somehow yet mean in terms of Jewish political rapid and seemingly irreversible rate. consider themselves Jewish or were influence and philanthropic support of In 1990 there were, according to either born to Jewish parents and/or Jewish causes and institutions is truly and at a rapid and seemingly this census report, 3,365,000 people had a Jewish upbringing, yet currently frightening to contemplate. living in the United States who were adhere to or practice a faith other than Judaism.