Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

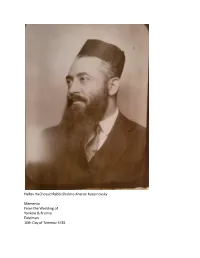

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC 2019-20 – HISTORICAL, MEDICAL and HALAKHIC PERSPECTIVES Second Edition Rabbi Prof

THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC RABBI PROF. AVRAHAM STEINBERG, MD THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC 2019-20 – HISTORICAL, MEDICAL AND HALAKHIC PERSPECTIVES Second Edition Rabbi Prof. Avraham Steinberg, MD Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Historical Background 3 a. Pandemics in the past b. The Coronavirus pandemic 3. Medical Background 5 4. Specific rulings and Halakhot 7 a. General behavior and the obligation to listen to the government and experts during a plague b. Defining plague c. Prayers, fasts and charity d. Self-endangerment of the healthcare providers – doctors, nurses, lab personnel, technicians e. Self-endangerment for experimental treatment and discovering a vaccine f. Prayer with a minyan, nesiyat kapayim, Torah reading, yeshivot g. Ha'gomel Blessing h. Shabbat and festivals i. Passover j. Sefirat Ha'omer k. Rosh Hashanah l. Yom Kippur m. Purim n. Immersion in the mikvah o. Immersion of utensils p. Visiting the sick q. Circumcision r. Marriage s. Burial t. Mourning 5. Triage in treating coronavirus patients during severe shortage 32 a. Introduction b. Determining triage priority in various situations when there are insufficient resources I am greatly indebted to Rabbi Dr. Jason Weiner for the English translation & to Dr. Lazar Friedman for his editorial work. 1 THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC RABBI PROF. AVRAHAM STEINBERG, MD c. Halakhic sources on determining lifesaving triage d. Halakhic guidelines on determining priority 6. Miscellaneous 40 7. Conclusion 41 1. Introduction In the modern era, the coronavirus1 pandemic2 has been the most shocking pandemic to the entire world, including experts and scientists, since the Spanish influenza pandemic 100 years ago.3 In recent decades many scientists have arrogantly claimed that in the modern and technologically advanced world there will be no more global pandemics of this sort. -

SHALOM Magazine August 2020

AUGUST 2020 AV- ELUL 5780 JNF AUSTRALIA SUPPORTING THE CHILDREN OF SDEROT WITH ANIMAL ASSISTED THERAPY 1964-2020 Celebrating 56 years JOIN THE JNF VIRTUAL of publishing GALA PROJECT LAUNCH GEORGE FREY OAM - FOUNDING EDITOR, 1964 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 - BOOK NOW BUILDING RESILIENCE, GROWING OUR FUTURE JNF VIRTUAL GALA 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 WITH SPECIAL INTERNATIONAL GUESTS FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY LORD JOHN MANN JASON ALEXANDER LIOR SUCHARD UK GOVT ANTISEMITISM TSAR ACTOR & COMEDIAN MENTALIST GAL GADOT MICHAEL ALONI EDEN ALENE HAGIT YASO ACCLAIMED CELEBRATED ISRAEL‘S EUROVISION PAST WINNER OF ACTRESS ACTOR 2020 REPRESENTATIVE ISRAELI IDOL TUESDAY 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 8:00PM - 9:00PM COMPLIMENTARY TICKETS BOOKINGS ESSENTIAL: WWW.JNF.ORG.AU/VIRTUALGALA OR 1300 563 563 BOOK NOW 2 SHALOM MAGAZINE | AV- ELUL 5780 THE JNF VIRTUAL GALA ON 1ST OF SEPTEMBER WILL BE SUPPORTING THE LATEST PROJECT OF JNF AUSTRALIA THE SDEROT RESILIENCE CENTRE In cooperation with the Municipality In addition, part of the complex will be of Sderot, JNF Australia will support allocated as an agility space for dog- the construction of the new Sderot assisted therapy. Resilience Centre to assist children living with PTSD. The connection between the child and the animals will give the child a sense of Animal-assisted therapy is an important responsibility as the animal’s caregiver, tool in helping to improve a patient’s and teach them to develop the skills for social, emotional, or cognitive dealing with crisis situations, making it functioning. easier to cope. The existing Animal-Assisted Therapy All the rooms in the Centre will be Centre was established three years ago, rocket-proof, negating the need to run providing treatment to hundreds of for cover during times of emergency. -

Shavuot Nation 5774

NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG ISRAEL Shavuot Nation 5774 JEWISH EDITION Compiled by Gabi Weinberg Teen Program Director ! Table of Contents Sources: Got Milk? Or, Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? page 4 Shiur Guide: Got Milk? Or, Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? page 7 Sources: Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? page 10 Shiur Guide: Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? page 12 Sources: Do Jews have horns? If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,!what!did!he!have?!page!20 Sources: Do Jews have horns? If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,!what!did!he!have?!page!24 Shiur Guide: Pronouncing the “Z” in Pizza – which bracha is right? page 28 Shiur Guide: Pronouncing the “Z” in Pizza, which bracha is right? page 32 12:00AM - 1:00AM Welcome and Opening Shiur: Got Milk? Or Perhaps we should be eating meat on Shavuot? • 1:00 - 1:10 Snack Break 1:15AM - 2:00AM Just Dress? Or is Tzniut something more? • 2:00 - 2:45 - Big Food, BBQ, Sushi or Alternative fun food 2:50AM - 3:35AM Sources:!Do!Jews!have!horns?!If!Moshe!didn't!have!horns,! what!did!he!have? • 3:35!B!3:45!Final!Snack!Break! 3:40AM!B!4:25AM!Pronouncing!the!“Z”!in!Pizza,!which!bracha!is!right?! • Wash!hands!and!Say!Brachot!Before!TePillah! 4:30!B!Shacharit!! Dear Young Israel Community, Shavuot is a special time of year where we put an extra emphasis on limmud Torah, study of Torah. The concept of a tikkun leil Shavuot, staying up all night immersed in Torah study, started as a kabbalistic custom that became popular across all sections of Judaism in the late 16th-century. -

Monatsschrift Für Geschichte Und Wissenschaft Des Judenthums

'^i^fiti 100 =00 iOO =o IS ico M^i^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto littp://www.archive.org/details/monatsschriftf59gese Monatsschrift FÜR GESCHICHTE UND WISSENSCHAFT DES JUDENTUMS BEGRÜNDET VON Z. FRANKEL. Organ der Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaft des Judentums Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. M. BRANN. Neunundfünfzigster Jahrgang. NEUE FOLGE, DREIUNDZWANZIGSTEB JAHRGANG. BRESLAU. KOEBNER'SCHE VERLAGSBUCHHANDLUNG. (BARASCH UND RIESENFELD.) 1915. Der jetzige Weltkrieg und die Bibel. Vortrag gehalten in der Wiener »Urania« am g. Januar 1915 von M. Güdemann. I. Nichts wird in der Bibel als so erstrebenswert hingestellt, kein Gut wird mit so warmen, eindringlichen Worten als der Güter höchstes gepriesen, wie der Friede. Der Priestersegen, der in allen Gotteshäusern, welcher Konfession sie dienen mögen, in verehrungsvoller Übung steht, lautet in seiner Kürze und Einfach- heit: »Der Herr segne dich und behüte dich. Der Herr lasse dir sein Antlitz leuchten und sei dir gnädig. Der Herr wende dir sein Antlitz zu und gebe dir Frieden.« Der ganze Satz ist bild- haft, nur ein Gut wird ausdrücklich namhaft gemacht und er- beten: das ist nicht Reichtum, nicht Ehre, Herrschaft, Macht und Größe, sondern dasjenige Gut, um das der Mächtigste, der es nicht besitzt, den Ärmsten beneidet, der es besitzt — der Friede. Wir werden diese hohe Veranschlagung des Friedens heute mehr als je begreifen, weil wir uns in einem Weltkriege, in einem Welt- brande befinden. Denn was heute alle im tiefsten Innern bewegt, was alle Herzen ausfüllt, alle Gemüter beseelt, das läßt sich unter Anwendung und entsprechender Umänderung eines be- kannten Goetheschen Satzes in die Worte zusammenfassen: »Nach Frieden drängt, am Frieden hängt doch alles«. -

CCAR Journal the Reform Jewish Quarterly

CCAR Journal The Reform Jewish Quarterly Halachah and Reform Judaism Contents FROM THE EDITOR At the Gates — ohrgJc: The Redemption of Halachah . 1 A. Brian Stoller, Guest Editor ARTICLES HALACHIC THEORY What Do We Mean When We Say, “We Are Not Halachic”? . 9 Leon A. Morris Halachah in Reform Theology from Leo Baeck to Eugene B . Borowitz: Authority, Autonomy, and Covenantal Commandments . 17 Rachel Sabath Beit-Halachmi The CCAR Responsa Committee: A History . 40 Joan S. Friedman Reform Halachah and the Claim of Authority: From Theory to Practice and Back Again . 54 Mark Washofsky Is a Reform Shulchan Aruch Possible? . 74 Alona Lisitsa An Evolving Israeli Reform Judaism: The Roles of Halachah and Civil Religion as Seen in the Writings of the Israel Movement for Progressive Judaism . 92 David Ellenson and Michael Rosen Aggadic Judaism . 113 Edwin Goldberg Spring 2020 i CONTENTS Talmudic Aggadah: Illustrations, Warnings, and Counterarguments to Halachah . 120 Amy Scheinerman Halachah for Hedgehogs: Legal Interpretivism and Reform Philosophy of Halachah . 140 Benjamin C. M. Gurin The Halachic Canon as Literature: Reading for Jewish Ideas and Values . 155 Alyssa M. Gray APPLIED HALACHAH Communal Halachic Decision-Making . 174 Erica Asch Growing More Than Vegetables: A Case Study in the Use of CCAR Responsa in Planting the Tri-Faith Community Garden . 186 Deana Sussman Berezin Yoga as a Jewish Worship Practice: Chukat Hagoyim or Spiritual Innovation? . 200 Liz P. G. Hirsch and Yael Rapport Nursing in Shul: A Halachically Informed Perspective . 208 Michal Loving Can We Say Mourner’s Kaddish in Cases of Miscarriage, Stillbirth, and Nefel? . 215 Jeremy R. -

UNVERISTY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative In

UNVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 © Copyright by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim by Zachary Alexander Klein Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Richard Dane Danielpour , Co-Chair Professor David Samuel Lefkowitz, Co-Chair In the Chabad-Lubavitch chasidic community, the singing of religious folksongs called nigunim holds a fundamental place in communal and individual life. There is a well-known saying in Chabad circles that while words are the pen of the heart, music is the pen of the soul. The implication of this statement is that music is able to express thoughts and emotions in a deeper way than words could on their own could. In chasidic thought, there are various spiritual narratives that may be expressed through nigunim. These narratives are fundamental in understanding what is being experienced and performed through singing nigunim. At times, the narrative has already been established in Chabad chasidic literature and knowing the particular aspects of this narrative is indispensible in understanding how the nigun unfolds in musical time. ii In other cases, the particular details of this narrative are unknown. In such a case, understanding how melodic construction, mode, ornamentation, and form function to create a musical syntax can inform our understanding of how a nigun can reflect a particular spiritual narrative. This dissertation examines the ways in which musical syntax and spiritual parameters work together to express these various spiritual narratives in sound and structure of nigunim. -

Minyan Vs. Medicine ... משנה שלוחי מצוה פטורין מן הסוכה ... " רט לעוסק במצוה פ

Minyan vs. Medicine R' Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] A core principle: One who is involved in a mitzvah is exempt from further mitzvot 1. Talmud, Succah 25a-b משנה שלוחי מצוה פטורין מן הסוכה... גמרא מנא הני מילי דתנו רבנן "'בשבתך בביתך' פרט לעוסק במצוה"... והעוסק במצוה פטור מן המצוה מהכא נפקא? מהתם נפקא דתניא "'ויהי אנשים אשר היו טמאים לנפש אדם וכו'' אותם אנשים מי היו? נושאי ארונו של יוסף היו, דברי רבי יוסי הגלילי. רבי עקיבא אומר מישאל ואלצפן היו שהיו עוסקין בנדב ואביהוא. רבי יצחק אומר אם נושאי ארונו של יוסף היו כבר היו יכולין ליטהר, אם מישאל ואלצפן היו יכולין היו ליטהר! אלא עוסקין במת מצוה היו..."! צריכא, דאי אשמעינן התם משום דלא מטא זמן חיובא דפסח, אבל הכא דמטא זמן קריאת שמע אימא לא, צריכא. ואי אשמעינן הכא משום דליכא כרת, אבל התם דאיכא כרת אימא לא, צריכא... תניא "אמר רבי חנניא בן עקביא כותבי ספרים תפילין ומזוזות הן ותגריהן ותגרי תגריהן וכל העוסקין במלאכת שמים לאתויי מוכרי תכלת פטורין מקריאת שמע ומן התפילה ומן התפילין ומכל מצות האמורות בתורה, לקיים דברי רבי יוסי הגלילי שהיה רבי יוסי הגלילי אומר העוסק במצוה פטור מן המצוה." תנו רבנן "הולכי דרכים ביום פטורין מן הסוכה ביום וחייבין בלילה. הולכי דרכים בלילה פטורין מן הסוכה בלילה וחייבין ביום. הולכי דרכים ביום ובלילה פטורין מן הסוכה בין ביום ובין בלילה. הולכין לדבר מצוה פטורין בין ביום ובין בלילה." Mishnah: Those who are on a mitzvah mission are exempt from Succah. Gemara: How do we know this? The sages taught, "'When you lie down in your house' excludes one who is involved in a mitzvah"… But do we learn [this lesson] from this source? It is deduced from that: "'And there were men who were impure from contact with the dead' – Who were those men? The bearers of Joseph's casket, per R' Yosi haGlili. -

Toronto Torah Beit Midrash Zichron Dov

בס“ד Toronto Torah Beit Midrash Zichron Dov Parshat Vayyigash 5 Tevet 5772/December 31, 2011 Vol.3 Num. 14 To sponsor an edition of Toronto Torah, please email [email protected] or call 416-781-1777 Age: More Than Just a Number Hillel Horovitz נדמיין לעצמנו מפגש פסגה בין שני מנהיגים אברהם בא ללמד אותנו כיצד יש לגשת לחיי משמעותית ביותר ולכן הן גם מקבלות משקל מהגדולים בעולם. האפיפיור מגיע לוושינגטון המעשה בעולמנו . עלינו למלא כל יום בעשייה רב כל כך בחיבור התורה. לפגוש את נשיא ארצות הברית . הנשיא רואה ולהבין שאין כל חשיבות בימים שעוברים עלינו נוכל גם לענות באמצעות כך על השאלה למולו את האפיפיור ואת המשלחת הנכבדה בעולם הזה מצד הזמן שעובר כי אם מצד התמידית שמהדהדת בין עולם התורה לעולם שעומדת לפניו ושואל לפתע : התוכן שאנו יוצקים אל תוך החיים הללו. המדע . כיצד ייתכן שלפי המדע העולם קיים "בן כמה אתה אדוני האפיפיור? אתה נראה די נוכל אולי באמצעות הבנה זו גם לעמוד על מאות מיליוני ואפילו מיליארדי שנים ואילו מבוגר!" דרכה של התורה בתיאור המהלכים לפי התורה העולם קיים רק 0222 שנה לערך . התיתכן מציאות שכזו ? האם היינו מעלים על ההיסטוריים הקורים בתוכה . במהלך התורה לפי ההבנה בפרשתנו נוכל להגיד גם כן , כי דעתנו שאחד ממנהיגי העולם ידבר כך ? כולה על חמישים וארבע פרשיותיה עוברים אנו יכול להיות שהעולם התקיים שנים רבות לפני כנראה שלא , זו נראית כשאלה מאוד אישית מהלך של 0022 שנה , ניתן לצפות בחישוב בריאת האדם אולם התורה מחשיבה את ואפילו חצופה ופוגעת , אולם בפרשת השבוע פשוט כי כל פרשה תספר על כחמישים שנה . העולם כקיים ונברא רק כאשר יש בתוכו אדם אנו מגלים שאין הדבר פשוט כלל וכלל . -

Davening with a Minyan

T December 25- January 1, 2020 • Tevet 10-17, 5781 This Week at YICC VAYIGASH m SHABBAT MINYANIM IN SHUL @ YICC HALAKHIC CORNER You MUST be pre-registered and on our security list to Q: Do any of the laws change when the fast of Asarah B'Tevet falls be allowed entry into our Minyanim. out on Friday? ALL Minyanim meet in our Shul’s Backyard A: From time to time, the fast of the 10th of Tevet falls out on Friday as it does this year. While we generally treat a Friday fast Erev Shabbat, Fri, Dec 25th (Fast-Tenth of Tevet) the same as we would treat a fast during the week, it is Fast Begins ..................................................... 5:37 am interesting to note that some Rabbis called for substantial Shacharit ......................................... 6:00/7:00/8:00 am changes as they relate to the Mincha prayers. Rav Yosef Karo, Mincha & Kabbalat Shabbat ........................... 4:25 pm in Beit Yosef (O”C 550), quotes the Shibolei HaLeket (Rabbi Fast Ends With Kiddush .......................... after 5:27 pm Tzidkeya ben Abraham Anaw, 1210 – 1280) who posits that when a fast occurs on Friday, the special Torah reading for a Shabbat Day: fast day is not read at Mincha in order to give people adequate time to properly prepare for Shabbat. Rabbi Avraham Gombiner Shacharit ........................................... 7:00 & 8:30 am in the Magen Avraham notes that the Mishna in Ta’anit teaches Shabbat Afternoon: the same law in a slightly different context. The Mishna records Mincha .......................................................... 4:30 pm that when special convoys of Israelite men would ascend the Shiur by Rabbi Dr. -

This Week at Nitzavim-Vayeilech

.4 September 12, 2020 23rd of Elul 5780 This Week At Nitzavim-Vayeilech SHABBAT MINYANIM IN SHUL @ YICC HALAKHIC CORNER You MUST be pre-registered and on our security list Q: Is one permitted to recite the prayer of Machnisei Rachamim at the end of the Selichot service in which we to be allowed entry into our Minyanim. beseech the angels to help present our prayers to G-d? ALL Minyanim meet in our Shul’s Backyard A: The 5th of the Rambam’s 13 Principles of Faith states that Friday Night: we believe that one must only pray to Hashem and to no other being. Precisely because of this belief, the Maharal Mincha & Kabbalat Shabbat ................. 6:55 pm (Netiv Olam) writes that the paragraph of Machnisei Rachami, one of the concluding prayers of the Selichot Shabbat Day: service this Motzei Shabbat, should be omitted since it is Shacharit .................................. 7:00 & 8:30 am a prayer to angels. Similarly, the Chatam Sofer (Sh”T Shabbat Afternoon: O”C 166) expresses his reservations about this prayer. Mincha .................................................. 6:40 pm He adds that he would regularly elongate his Tachanun at Shiur by Rabbi Proops the conclusion of Selichot so that by the time he was Maariv................................................... 7:38 pm ready to recite Machnisei Rachamim the Chazan had already concluded the service thereby circumventing the Shabbat ends & Havdalah .................... 7:48 pm issue altogether. Interestingly, Rabbi Asher Weiss (Minchas Asher - Moadim) opines that reciting Machnisei SHABBAT AT HOME Rachamim is completely permitted. He reasons that when the Rambam prohibited praying to other beings, the Shabbat Candle Lighting .................. -

Wordplay in Genesis 2:25-3:1 and He

Vol. 42:1 (165) January – March 2014 WORDPLAY IN GENESIS 2:25-3:1 AND HE CALLED BY THE NAME OF THE LORD QUEEN ATHALIAH: THE DAUGHTER OF AHAB OR OMRI? YAH: A NAME OF GOD THE TRIAL OF JEREMIAH AND THE KILLING OF URIAH THE PROPHET SHEPHERDING AS A METAPHOR SAUL AND GENOCIDE SERAH BAT ASHER IN RABBINIC LITERATURE PROOFTEXT THAT ELKANAH RATHER THAN HANNAH CONSECRATED SAMUEL AS A NAZIRITE BOOK REVIEW: ONKELOS ON THE TORAH: UNDERSTANDING THE BIBLE BOOK REVIEW: JPS BIBLE COMMENTARY: JONAH LETTER TO THE EDITOR www.jewishbible.org THE JEWISH BIBLE QUARTERLY In cooperation with THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, THE JEWISH AGENCY AIMS AND SCOPE The Jewish Bible Quarterly provides timely, authoritative studies on biblical themes. As the only Jewish-sponsored English-language journal devoted exclusively to the Bible, it is an essential source of information for anyone working in Bible studies. The Journal pub- lishes original articles, book reviews, a triennial calendar of Bible reading and correspond- ence. Publishers and authors: if you would like to propose a book for review, please send two review copies to BOOK REVIEW EDITOR, POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel. Books will be reviewed at the discretion of the editorial staff. Review copies will not be returned. The Jewish Bible Quarterly (ISSN 0792-3910) is published in January, April, July and October by the Jewish Bible Association , POB 29002, Jerusalem, Israel, a registered Israe- li nonprofit association (#58-019-398-5). All subscriptions prepaid for complete volume year only. The subscription price for 2014 (volume 42) is $60. Our email address: [email protected] and our website: www.jewishbible.org .