Nova Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

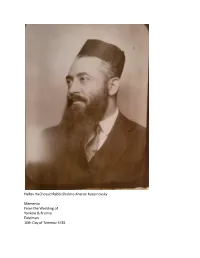

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

301 Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon By: ZVI RON In this article we investigate the origin and development of saying vari- ous Psalms and selected verses from Psalms before Birkat Ha-Mazon. In particular, we will attempt to explain the practice of some Ashkenazic Jews to add Psalms 145:21, 115:18, 118:1 and 106:2 after Ps. 126 (Shir Ha-Ma‘alot) and before Birkat Ha-Mazon. Psalms 137 and 126 Before Birkat Ha-Mazon The earliest source for reciting Ps. 137 (Al Naharot Bavel) before Birkat Ha-Mazon is found in the list of practices of the Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero (1522–1570). There are different versions of this list, but all versions include the practice of saying Al Naharot Bavel.1 Some versions specifically note that this is to recall the destruction of the Temple,2 some versions state that the Psalm is supposed to be said at the meal, though not specifically right before Birkat Ha-Mazon,3 and some versions state that the Psalm is only said on weekdays, though no alternative Psalm is offered for Shabbat and holidays.4 Although the ex- act provenance of this list is not clear, the parts of it referring to the recitation of Ps. 137 were already popularized by 1577.5 The mystical work Seder Ha-Yom by the 16th century Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe ben Machir was first published in 1599. He also mentions say- ing Al Naharot Bavel at a meal in order to recall the destruction of the 1 Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalah in Liturgy, Halakhah and Customs (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2000), pp. -

Redalyc.Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII Th–XIX Th Centuries

REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña E-ISSN: 1659-4223 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Khalturin, Yuriy Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysicsin Russian Freemasonry of the XVIII th–XIX th centuries REHMLAC. Revista de Estudios Históricos de la Masonería Latinoamericana y Caribeña, vol. 7, núm. 1, mayo-noviembre, 2015, pp. 128-140 Universidad de Costa Rica San José, Costa Rica Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=369539930009 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, Vol. 7, no. 2, Mayo - Noviembre 2015/ 128-140 128 Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the XVIIIth – XIXth centuries Yuriy Khalturin PhD in Philosophy (Russian Academy of Science), independent scholar, member of ESSWE. E-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recibido: 20 de noviembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 8 de enero de 2015 Palabras clave Cábala, masonería, rosacrucismo, teosofía, sofilogía, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanación, alquimia, la estrella llameante, columnas Jaquín y Boaz Keywords Kabbalah, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Sophiology, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanation, alchemy, Flaming Star, Columns Jahin and Boaz Resumen Este trabajo considera algunas conexiones entre la Cábala y la masonería en Rusia como se refleja en los archivos del Departamento de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Estatal Rusa (DMS RSL). El vínculo entre ellos se basa en la comprensión tanto de la Cabala y la masonería como la filosofía simbólica y “verdaderamente metafísica”. -

Cross on the Star of David: the Christian World in Israel's Foreign Policy, 1948-1967 REVIEW

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 3(2008): R1-2 REVIEW Uri Bialer Cross on the Star of David: The Christian World in Israel’s Foreign Policy, 1948-1967 Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005, 233 pp. Reviewed by Michael B. McGarry, Tantur Ecumenical Institute, Jerusalem Over the last few decades, scholarly interest in political relations between the Christian world and the State of Israel has focused primarily on the Roman Catholic Church’s view of the Zionist movement (before the founding of the State) and its perceived slowness in establishing full diplomatic relations with the Jewish State. But here in his Cross on the Star of David: The Christian World in Israel’s Foreign Policy, 1948-1967, Dr. Uri Bialer addresses the question in the opposite direction. Drawing on Israel’s diplomatic history from 1948 to the 1967 war, Dr. Bialer traces the attitude and actions of the fledgling Jewish state towards the Christian world. Currently occupying the chair in International Relations – Middle East Studies in the Department of International Relations at the Hebrew University, Dr. Bialer has opened up a seldom- addressed topic both fascinating and illuminating: In its first twenty years, how did the new-born State of Israel, in its foreign diplomacy and internal policies, address the Christian world? Bialer, a perspicacious historian with the necessary language skills to analyze recently declassified (1980) Israeli governmental archives, recognizes and honors the complexity of his topic. He carefully notes the multiple factors affecting the new state’s diplomats and policy makers in assessing their delicate but forceful formulation of policy towards the Christian world – both those Christians living in Israel and those countries, often overwhelmingly Christian, whose support the young state desperately needed, even and maybe especially after its United Nations’ authorization. -

“Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782

Jewish Day School “Cliff Notes” 2021-2022 5781-5782 A quick run-down with need-to-know info on: • Jewish holidays • Jewish language • Jewish terms related to prayer service SOURCES WE ACKNOWLEDGE THAT THE INFORMATION FOR THIS BOOKLET WAS TAKEN FROM: • www.interfaithfamily.com • Living a Jewish Life by Anita Diamant with Howard Cooper FOR MORE LEARNING, YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN THE FOLLOWING RESOURCES: • www.reformjudaism.org • www.myjewishlearning.com • Jewish Literacy by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin • The Jewish Book of Why by Alfred J. Kolatch • The Jewish Home by Daniel B. Syme • Judaism for Dummies by Rabbi Ted Falcon and David Blatner Table of Contents ABOUT THE CALENDAR 5 JEWISH HOLIDAYS Rosh haShanah 6 Yom Kippur 7 Sukkot 8 Simchat Torah 9 Chanukah 10 Tu B’Shevat 11 Purim 12 Pesach (Passover) 13 Yom haShoah 14 Yom haAtzmaut 15 Shavuot 16 Tisha B’Av 17 Shabbat 18 TERMS TO KNOW A TO Z 20 About the calendar... JEWISH TIME- For over 2,000 years, Jews have juggled two calendars. According to the secular calendar, the date changes at midnight, the week begins on Sunday, and the year starts in the winter. According to the Hebrew calendar, the day begins at sunset, the week begins on Saturday night, and the new year is celebrated in the fall. The secular, or Gregorian calendar is a solar calendar, based on the fact that it takes 365.25 days for the earth to circle the sun. With only 365 days in a year, after four years an extra day is added to February and there is a leap year. -

STAR of DAVID the COSMIC COUNTDOWN Alignments, Symmetry and Patterns from 1990-2013

STAR OF DAVID THE COSMIC COUNTDOWN Alignments, Symmetry and Patterns from 1990-2013 By Luis B. Vega [email protected] The purpose of this study is to highlight a key celestial occurrence in the Heavens called the Star of David planetary alignments. The focus of the timeline presented will be from the most recent occurrences in our modern time. Starting from 1990 to 2013, these peculiar planetary alignments seem to be clustered. In particular, since 1990, there are 13 Star of David configurations that occurs leads up to the Tetrad of 2014-2015. The 13th occurrence* is the ‘last one’ leading up to the Tetrad of 2014-2015. *As the date rage is noted on the chart as being from July 22 - Aug 26, 2013 the 13th alignment is a ‘twin’ star with its double occurring on Aug 25/26. The time difference from the first ‘Twin’ Star to occur in 1996 to the ‘Twin’ Star of 2013 is 17 years. What is sort of similar is that the Twin Star of 1996 to the Tetrad of 2003 is 7 years. After 2013, there will not be another such configuration of either a Tetrad or Star of David alignment associated with a Tetrad for another 100 years or so. The Star of David alignments appears to follow a ‘countdown’ sequence or frequency of sorts. It very much appears to be like the Total Solar Eclipses that occurred consecutively on the 1st of Av in 2008, 2009 and 2010. Those 3 consecutive Eclipses appeared to signal the ‘countdown’ to the start of the 7-Year Solar-Lunar pattern. -

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner

Jason Yehuda Leib Weiner A Student's Guide and Preparation for Observant Jews ♦California State University, Monterey Bay♦ 1 Contents Introduction 1 Chp. 1, Kiddush/Hillul Hashem 9 Chp. 2, Torah Study 28 Chp. 3, Kashrut 50 Chp. 4, Shabbat 66 Chp. 5, Sexual Relations 87 Chp. 6, Social Relations 126 Conclusion 169 2 Introduction Today, all Jews have the option to pursue a college education. However, because most elite schools were initially directed towards training for the Christian ministry, nearly all American colonial universities were off limits to Jews. So badly did Jews ache for the opportunity to get themselves into academia, that some actually converted to Christianity to gain acceptance.1 This began to change toward the end of the colonial period, when Benjamin Franklin introduced non-theological subjects to the university. In 1770, Brown University officially opened its doors to Jews, finally granting equal access to a higher education for American Jews.2 By the early 1920's Jewish representation at the leading American universities had grown remarkably. For example, Jews made up 22% of the incoming class at Harvard in 1922, while in 1909 they had been only 6%.3 This came at a time when there were only 3.5 millions Jews4 in a United States of 106.5 million people.5 This made the United States only about 3% Jewish, rendering Jews greatly over-represented in universities all over the country. However, in due course the momentum reversed. During the “Roaring 1920’s,” a trend towards quotas limiting Jewish students became prevalent. Following the lead of Harvard, over seven hundred liberal arts colleges initiated strict quotas, denying Jewish enrollment.6 At Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons for instance, Jewish enrollment dropped from 50% in 1 Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1959), 557. -

The Jews of Simferopol

BE'H The Jews of Simferopol This article is dedicated to two of our grandsons who are now Israeli soldiers: Daniel Prigozin and Yonaton Inegram. Esther (Herschman) Rechtschafner Kibbutz Ein-Zurim 2019 Table of Contents Page Introduction 1 Basic Information about Simferopol 2 Geography 2 History 3 Jewish History 4 The Community 4 The Holocaust 6 After the Holocaust 8 Conclusion 11 Appendices 12 Maps 12 Photos 14 Bibliography 16 Internet 16 Introduction The story of why I decided to write about the history of Simferopol is as follows. As many know, I have written a few articles and organized a few websites1. All of these are in connection to the places in Eastern Europe that my extend family comes from. A short while ago Professor Jerome Shapiro2,who had previously sent me material about his family for my Sveksna website wrote me an email and mentioned that he would like to have an article written about the place where his wife's family comes from: Simferopol, Crimea. Since I did not know anything about this place, I decided to take this upon myself as a challenge. This meant: 1. researching a place that I am not emotionally attached to 2. finding material about a place that is not well known 3. finding a website for placement of the article With the help of people I know by way of my previous researching3, people I met while looking for information, the internet (and the help of G-d), I felt that I had enough information to write an article. While researching for material for this article, I became acquainted with Dr. -

Igbos: the Hebrews of West Africa

Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa by Michelle Lopez Wellansky Submitted to the Board of Humanities School of SUY Purchase in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Purchase College State University of New York May 2017 Sponsor: Leandro Benmergui Second Reader: Rachel Hallote 1 Igbos: The Hebrews of West Africa Michelle Lopez Wellansky Introduction There are many groups of people around the world who claim to be Jews. Some declare they are descendants of the ancient Israelites; others have performed group conversions. One group that stands out is the Igbo people of Southeastern Nigeria. The Igbo are one of many groups that proclaim to make up the Diasporic Jews from Africa. Historians and ethnographers have looked at the story of the Igbo from different perspectives. The Igbo people are an ethnic tribe from Southern Nigeria. Pronounced “Ee- bo” (the “g” is silent), they are the third largest tribe in Nigeria, behind the Hausa and the Yoruba. The country, formally known as the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is in West Africa on the Atlantic Coast and is bordered by Chad, Cameroon, Benin, and Niger. The Igbo make up about 18% of the Nigerian population. They speak the Igbo language, which is part of the Niger-Congo language family. The majority of the Igbo today are practicing Christians. Though they identify as Christian, many consider themselves to be “cultural” or “ethnic” Jews. Additionally, there are more than two million Igbos who practice Judaism while also reading the New Testament. In The Black -

The Month of Elul Is the Last Month of the Jewish Civil Year

The Jewish Month of Elul A Month of Mercy and Forgiveness Hodesh haRahamin vehaSelihot The month of Elul is the last month of the Jewish civil year. However, according to the biblical Calendar, it is also the sixth month, counting from Nisan which is called the “first of the months” in the Torah (Ex. 12:2). This document explores the spirituality of Elul for Jews and Judaism. Etz Hayim—“Tree of Life” Publishing “It is a Tree of Life to all who hold fast to It” (Prov. 3:18) The Month of Elul The month of Elul1 is the last month of the Jewish civil year. However, according to the biblical Calendar, it is also the sixth month, counting from Nisan which is called the “first of the months” in the Torah (Ex. 12:2). Elul precedes the month of Tishrei (called the seventh month, Numbers 29:1). Placed as the last of the months and followed by the New Year, Elul invites an introspective reflection on the year that has been. Elul begins the important liturgical season of Return and Repentance which culminates with Rosh HaShanah,2 the Days of Awe3 and Yom Kippur4 (1-10 Tishrei). Elul takes its place as an important preparation time for repentance. Elul follows the months of Tammuz and Av, both catastrophic months for Israel according to tradition. Tammuz is remembered as the month in which the people of Israel built the Golden Calf (Ex. 32) and Av, the month of the sin of the spies (Num. 13). The proximity of Tammuz and Av to Elul underscores the penitential mode of this, the last of the months, before the new beginning and spiritual re-creation that is precipitated with the New Year beginning the following month of Tishrei. -

Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the Xviiith – Xixth Centuries

REHMLAC+, ISSN 1659-4223, Vol. 7, no. 2, Mayo - Noviembre 2015/ 128-140 128 Kabbalah, Symbolism and Metaphysics in Russian Freemasonry of the XVIIIth – XIXth centuries Yuriy Khalturin PhD in Philosophy (Russian Academy of Science), independent scholar, member of ESSWE. E-mail: [email protected] Fecha de recibido: 20 de noviembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 8 de enero de 2015 Palabras clave Cábala, masonería, rosacrucismo, teosofía, sofilogía, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanación, alquimia, la estrella llameante, columnas Jaquín y Boaz Keywords Kabbalah, Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Sophiology, Sephiroth, Ein-Soph, Adam Kadmon, emanation, alchemy, Flaming Star, Columns Jahin and Boaz Resumen Este trabajo considera algunas conexiones entre la Cábala y la masonería en Rusia como se refleja en los archivos del Departamento de Manuscritos de la Biblioteca Estatal Rusa (DMS RSL). El vínculo entre ellos se basa en la comprensión tanto de la Cabala y la masonería como la filosofía simbólica y “verdaderamente metafísica”. En el artículo se muestra cómo los masones rusos adoptaron doctrinas cabalísticas de Ein-Soph, Sephiroth, Adam Kadmon y los mezclan con la teoría del neoplatonismo de la emanación, el misticismo cristiano apofática, la cosmovisión hermética, la alquimia y la sofilogía cristiana. Esta adaptación ecléctica se basa en la interpretación de estos símbolos masónicos como punto en un círculo, columnas Jaquín y Boaz, y la estrella flameante. El simbolismo masónico permitió la combinación de diferentes doctrinas esotéricas en una cosmovisión unificada para hacer símbolos masónicos más atractivos para la “medio educada” nobleza rusa. Abstract This paper considers some connections between Kabbalah and Freemasonry in Russia as reflected in the archives of the Department of Manuscripts of the Russian State Library (DMS RSL). -

Judaism Religion Video Symbol the Six-Pointed Star of David Is The

Judaism Religion Video https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/znwhfg8/articles/zh77vk7 Symbol The six-pointed Star of David is the symbol of Judaism. Founder God first revealed himself to a Hebrew man named Abraham, who became known as the founder of Judaism. Jews believe that God made a special covenant with Abraham and that he and his descendants were chosen people who would create a great nation. Place of Worship Jewish people attend services at the synagogue on Saturdays during Shabbat. Shabbat (the Sabbath) is the most important time of the week for Jews. It begins on Friday evenings and ends at sunset on Saturdays. During Shabbat, Jews remember that God created the world and on the seventh day he rested. Jews believe God's day of rest was a Saturday. The services in the synagogue are led by a religious leader called a rabbi, which means ‘Teacher’ in Hebrew. Holy book The Jewish holy book is called the Torah. The Torah is written in Hebrew. It is the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Christians call this book The Old Testament. The Torah has 613 commandments which are called mitzvah. They are the rules that Jews try to follow. The most important ones are the Ten Commandments. The Torah is so special that people are not allowed to touch it. It is kept in a safe place called an ark in the Jewish temple and when people read from the Torah, they use a special pointer stick called a yad to follow the words. Special Holidays Jewish people observe several important days and events in history, such as: Passover: This holiday lasts seven or eight days and celebrates Jewish freedom from slavery in Egypt.