Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

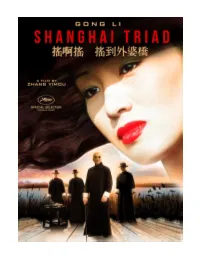

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

I Cento Passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) Is Giordana's Biopic About Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a Leftist Anti-Mafia Activist Murdered in Sicily in 1978

33 Marco Tullio Giordana' s The Hundred Steps: The Biopic as Political Cinema GEORGE DE STEFANO During the 1980s, the political engagement that fuelled much of Italy's postwar realist cinema nearly vanished, a casualty of both the domin ance of television and the decline of the political Left. The generation of great postwar auteurs - Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, and Pier Paolo Pasolini - had disappeared. Their departure, notes Millicent Marcus, was followed by 'the waning of the ideological and generic impulses that fueled the revolutionary achievement of their successors: Rosi, Petri, Bertolucci, Bellocchio, Ferreri, the Tavianis, Wertmuller, Cavani, and Scola.' 1 The decline of political cinema was inextricable from the declining fortunes of the Left following the vio lent extremism of the 1970s, the so-called leaden years and, a decade later, the fall of Communism. The waning of engage cinema continued throughout the 1990s, with a few exceptions. But as the twentieth cen tury drew to a close, the director Marco Tullio Giordana made a film that represented a return to the tradition of political commitment. I cento passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) is Giordana's biopic about Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a leftist anti-Mafia activist murdered in Sicily in 1978. The film was critically acclaimed, winning the best script award at the Venice Film Festival and acting awards for two of its stars. It was a box office success in Italy, with its popularity extending beyond the movie theatres. Giordana's film, screened in schools and civic as sociations throughout Sicily, became a consciousness-raising tool for anti-Mafia forces, as well as a memorial to a fallen leader of the anti Mafia struggle. -

Thatcher Alle Corde Sgrida Martelli Eliache Svanisce La Minaccia Militare

Giornale + Salvagente L. 1500 Giornale Anno 67°, n. 105 Spedizione m abb. post. gr. 1/70 del Partito arretrati L. 3300 comunista T'Unita italiano 5 maggio 1990 La dottrina Bush: «Una Nato I laburisti col 43% (+11%) sorpassano i conservatori (31%) che perdono 12 punti Bobbio e Occhietto perplessi più politica* Avanzata tory solo in alcuni distretti londinesi. Annunciato un minirimpasto di governo sul verdetto contro Loto continua «C li Stati Uniti devono restare una potenza europea nel sen- sc più ampio, dal punto di vista politico, militare ed econo mici:». Bush (nella foto) teme che gli Usa vengano tagliati fuori dal processo di unificazione europea, per questo rilan- Andreotti cii II vertice "costituente»della Nato, in programma perfine pijgno. L'Alleanza atlantica - dice il presidente - deve •prendere in considerazione la sua futura missione politica» Thatcher alle corde sgrida Martelli eliache svanisce la minaccia militare. A PAGINA 5 In autostrada Ci si avvia alla fine delle lun ghe ed estenuami code nei con il Telepass caselli delle autostrade? Da sul caso Sofri peir evitare lunedi sull'Autosole, a Mila La destra battuta nel suo «tempio» no, a Roma e a Napoli, in via li! lunghe code sperimentale, va in funzione il Telepass, un sistema tele Per i conservatori è stato un autentico tracollo. Martelli sconfessalo da Andreotti. Sul caso Sofri scen malico che consente all'au- C'è anche Nelle amministrative di giovedì i tories sono calati de in campo il presidente del Consiglio per criticare il tcmobilista di entrare ed uscire senza fermare il veicolo. Il del 12% rispetto al risultato ottenuto nelle ultime suo vice e polemizzare con «quel mondo culturale percorso ed il pedaggio viene registrato attraverso un appa elezioni politiche tre anni fa. -

Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´Y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha)

Journal of Film Preservation Contributors to this issue... Ont collaboré à ce numéro... Journal Han participado en este número... 73 04/2007 ANTTI ALANEN of Film Head of the FIAF Programming and Access to KAE ISHIHARA Collections Commission, Programmer at the Finnish Film Archive Film archivist, Head of Film Preservation Society (Helsinki) (Tokyo) Preservation RENÉ BEAUCLAIR JEANICK LE NAOUR Directeur de la Médiathèque Guy L. Côté, Responsable de la Cinémathèque Afrique (Paris) Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) ÉRIC LE ROY EILEEN BOWSER Chef du Service accès, valorisation et Film historian, Honorary Member of FIAF (New enrichissement des collections, Archives York) françaises du film-CNC (Bois d’Arcy) PAOLO CHERCHI USAI PATRICK LOUGHNEY Director, National Film and Sound Archive Senior Curator, George Eastman House - Motion (Canberra) Picture Department (Rochester) Revista de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA NWANNEKA OKONKWO Film archivist, Cinemateca portuguesa / Museo Head of the do cinema (Lisbon) National Film Video and Sound Archive (Jos) ROBERT DAUDELIN VLADIMIR OPELA Rédacteur en chef du Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha) MARCO DE BLOIS PAULO EMILIO SALLES GOMES the by Published International Federation of Film Archives Conservateur cinéma d’animation, Film scholar and archivist (1929 -1977) (São Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) Paulo) CHRISTIAN DIMITRIU ROGER SMITHER Éditeur et membre du comité de rédaction du Keeper, Film and Video -

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative Carmela Coccimiglio Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Carmela Coccimiglio, Ottawa, Canada, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One 27 “Senza Mamma”: Mothers, Stereotypes, and Self-Empowerment Chapter Two 57 “Three Corners Road”: Molls and Triangular Relationship Structures Chapter Three 90 “[M]arriage and our thing don’t jive”: Wives and the Precarious Balance of the Marital Union Chapter Four 126 “[Y]ou have to fucking deal with me”: Female Gangsters and Textual Outcomes Chapter Five 159 “I’m a bitch with a gun”: African-American Female Gangsters and the Intersection of Race, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Conclusion 186 Works Cited 193 iii ABSTRACT Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative investigates women characters in American gangster narratives through the principal roles accorded to them. It argues that women in these texts function as an “absent presence,” by which I mean that they are a convention of the patriarchal gangster landscape and often with little import while at the same time they cultivate resistant strategies from within this backgrounded positioning. Whereas previous scholarly work on gangster texts has identified how women are characterized as stereotypes, this dissertation argues that women characters frequently employ the marginal positions to which they are relegated for empowering effect. This dissertation begins by surveying existing gangster scholarship. There is a preoccupation with male characters in this work, as is the case in most gangster texts themselves. -

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019

Copyright by Amanda Rose Bush 2019 The Dissertation Committee for Amanda Rose Bush Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso Buscetta Committee: Paola Bonifazio, Supervisor Daniela Bini Circe Sturm Alessandra Montalbano Self-presentation, Representation, and a Reconsideration of Cosa nostra through the Expanding Narratives of Tommaso by Amanda Rose Bush Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 Dedication I dedicate this disseration to Phoebe, my big sister and biggest supporter. Your fierce intelligence and fearless pursuit of knowledge, adventure, and happiness have inspired me more than you will ever know, as individual and as scholar. Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the sage support of Professor Paola Bonifazio, who was always open to discussing my ideas and provided both encouragement and logistical prowess for my research between Corleone, Rome, Florence, and Bologna, Italy. Likewise, she provided a safe space for meetings at UT and has always framed her questions and critiques in a manner which supported my own analytical development. I also want to acknowledge and thank Professor Daniela Bini whose extensive knowledge of Sicilian literature and film provided many exciting discussions in her office. Her guidance helped me greatly in both the genesis of this project and in understanding its vaster implications in our hypermediated society. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Circe Sturm and Professor Alessandra Montalbano for their very important insights and unique academic backgrounds that helped me to consider points of connection of this project to other larger theories and concepts. -

L'italiano Al Cinema, L'italiano Del Cinema

spacca LA LINGUA ITALIANA NEL MONDO Nuova serie e-book L’ebook è molto di + Seguici su facebook, twitter, ebook extra spacca © 2017 Accademia della Crusca, Firenze – goWare, Firenze ISBN 978-88-6797-874-8 LA LINGUA ITALIANA NEL MONDO. Nuova serie e-book Nessuna parte del libro può essere riprodotta in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo senza l’autorizzazione dei proprietari dei diritti e dell’editore. Accademia della Crusca Via di Castello 46 – 50141 Firenze +39 055 454277/8 – Fax +39 055 454279 Sito: www.accademiadellacrusca.it Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AccademiaCrusca Twitter: https://twitter.com/AccademiaCrusca YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/AccademiaCrusca Contatti: http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/it/contatta-la-crusca goWare è una startup fiorentina specializzata in nuova editoria Fateci avere i vostri commenti a: [email protected] Blogger e giornalisti possono richiedere una copia saggio a Maria Ranieri: [email protected] Redazione a cura di Dalila Bachis Copertina: Lorenzo Puliti Premessa La storia della lingua italiana del Novecento è legata a quella del cinema a doppio no- do: inscenando dapprima l’italiano letterario nelle didascalie del muto e nei dialoghi d’ascendenza teatrale del primo sonoro, per poi dar voce sempre più spesso a tutte le varietà d’Italia, lo schermo, più che da diaframma, ha fatto da mezzo di continuo in- terscambio tra usi reali e riprodotti. Lo testimonia, tuttora, la ricca messe di “filmismi” nell’italiano di tutti i giorni, da quarto potere all’attimo fuggente, dall’Armata Branca- leone alla grande abbuffata, alcuni dei quali migrati addirittura in molte altre lingue del mondo, come i fellinismi dolcevita e paparazzo. -

Hoods and Yakuza the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Hoods and Yakuza The Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film. Pate, Simon The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/13034 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Hoods and Yakuza: the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film 1 Hoods and Yakuza The Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film by Simon Pate Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages, Linguistics and Film Queen Mary University of London March 2016 Hoods and Yakuza: the Shared Myth of the American and Japanese Gangster Film 2 Statement of Originality I, Simon Pate, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. -

Uba-Foundation-Fine-Boys.Pdf

Praise for Fine Boys ‘Fine Boys is the first African novel I know that takes us deep into the world of the children of IMF: those post-Berlin wall Africans, like myself, who came of age in the days of The Conditionalities, those imposed tools and policies that made our countries feral; the days that turned good people into beasts, the days that witnessed the great implosion and scattering of the middle classes of a whole continent. Fine Boys takes us deep into the lives of the notorious gangs that took over universities all over Nigeria in the 1990s and early this century. We saw our universities collapse, and we struggled to educate ourselves through very harsh times. It is a beautifully written novel, heartfelt, deeply knowledgeable, funny, a love story, a tragedy; an important book, a book of our times; a book for all Africans everywhere.’ —Binyavanga Wainaina, author of One Day I Will Write about This Place ‘With Fine Boys, Eghosa Imasuen proves himself to be a keen observer of Nigerian urban life. He has written an unflinching and witty book, difficult to resist, impossible to ignore. He imbues his energetic prose and compelling characters with candour, grace, and pidgin inventiveness. A writer to watch.’ —A. Igoni Barrett, author of From Caves of Rotten Teeth ‘In Fine Boys, Imasuen writes fearlessly and beautifully of friend- ship, love, loss, and betrayal. It is thought-provoking, perfectly paced, uniformly delightful, compassionate, full of humour but also heart-breaking. Eghosa Imasuen has remarkable gifts.’ —Chika Unigwe, author -

The United States As Seen Through French and Italian Eyes

FANTASY AMERICA: THE UNITED STATES AS SEEN THROUGH FRENCH AND ITALIAN EYES by MARK HARRIS M.A., The University of British Columbia, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Programme in Comparative Literature) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1998 © Mark Robert Harris, 1998 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) - i i - Abstract For the past two decades, scholars have been reassessing the ways in which Western writers and intellectuals have traditionally misrepresented the non-white world for their own ideological purposes. Orientalism, Edward Said's ground-breaking study of the ways in which Europeans projected their own social problems onto the nations of the Near East in an attempt to take their minds off the same phenomena as they occurred closer to home, was largely responsible for this shift in emphasis. Fantasy America: The United States as Seen Through French and Italian Eyes is an exploration of a parallel occurrence that could easily be dubbed "Occidentalism." More specifically, it is a study of the ways in which French and Italian writers and filmmakers have sought to situate the New World within an Old World context. -

The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 2/9/20, 9'57 PM

Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 2/9/20, 9'57 PM ISSN 1554-6985 VOLUME IV · NUMBER (/current) 2 SPRING/SUMMER 2009 (/previous) EDITED BY (/about) Christy Desmet and Sujata (/archive) Iyengar CONTENTS "Nisht kayn Desdemona, nisht kayn Dzulieta": Yiddish Farrah Adaptations of The Merchant of Venice and the Early Modern Lehman Father-Daughter Bond (/782243/show) (pdf) (/782243/pdf) Time Lord of Infinite Space: Celebrity Casting, Andrew Romanticism, and British Identity in the RSC's "Doctor Who James Hamlet" (/782252/show) (pdf) (/782252/pdf) Hartley A SIAN SHAKESPEARES ON SCREEN: TWO F ILMS IN PERSPECTIVE E DITED BY ALEXA HUANG Alexa Introduction (/1404/show) (pdf) (/1404/pdf) Huang Mark Extending the Filmic Canon: The Banquet and Maqbool Thornton (/1405/show) (pdf) (/1405/pdf) Burnett Martial Arts and Masculine Identity in Feng Xiaogang's The Yu Jin Ko http://borrowers.uga.edu/7158/toc Page 1 of 3 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation 2/9/20, 9'57 PM Banquet (/1406/show) (pdf) (/1406/pdf) Amy Shakespeare: It's What's for Dinner (/1407/show) (pdf) Scott- (/1407/pdf) Douglass Woodcocks to Springes: Generic Disjunction in The Banquet Scott (/1410/show) (pdf) (/1410/pdf) Hollifield Spectator Violence and Queenly Desire in The Banquet Rebecca (/1411/show) (pdf) (/1411/pdf) Chapman Interiority, Masks, and The Banquet (/1413/show) (pdf) Yuk Sunny (/1413/pdf) Tien The Banquet as Cinematic Romance (/1414/show) (pdf) Charles (/1414/pdf) Ross A Thousand Universes: Zhang Ziyi in Feng Xiaogang's The Woodrow Banquet (/1418/show) (pdf) (/1418/pdf) B. -

Robbing Hood

Robbing Hood Re-appropriation of an African-American ‘keeping it real’ in hip-hop through the sampling of films, during times of glocalization and appropriation Stef Mul 10523537 Erik Laeven Second reader: Catherine Lord Word Count: 17.936 PREFACE Hip-hop is, and has from the very first beat, rhyme and dance, been a culture with a certain narrative. One that for purists and originators might be seen as lead astray in a globalizing circus of commercialization and remediation of itself, handing this hip-hop narrative over to people, who do not stem from the streets of suburban New York and of African-American decent, initially, as well as Latin- Americans and other ethnic minorities living in these same neighborhoods. Hip- hop artists are often anxious to defend its own original ethnical and socio- geographical confines. “First there was African music,” Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson firmly states in his book about his life as a hip-hop artist – among other things. “You know how Public Enemy says, in “Can’t Truss It,” that they came from “the base motherland, the place of the drums”? Africa, that’s the place they’re talking about,” quoting the hip-hop moguls, formed in 1986 (9). If one feels like subscribing to these thoughts, they might agree on the idea that the authentic culture of hip-hop stems from 1970 to 1979 and is interwoven with a great deal of African heritage. This was “before hip-hop was “commercialized” in the form of recordings,” according to some of the firmest purist fans, artists and scientists out there (Justin A.