Robbing Hood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Statesman, V.49, N. 50.PDF

the stony brook Statesman -.~---~~~'---------------~~--~~-~---~- - ------- I--- ~~~---~--I-I---1- VOLUME XLIX, ISSUE 48 THURSDAY MAY 4, 2006 PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY Campus Wide UREA Celebration Impresses A L' Inits 5tn year, tne annuai celeoration or unaergraduate researcn and creativity was neic last week. URECA Celebration photos: ©John Griffin/Media Services Photography, Art Show photos: ©Jeanne Neville/Media Services Photography BY Sunr RAMBHIA and Sociology." Kudos goes to the Department of Bio- News Editor medical Engineering, which had the greatest number of abstract submissions, 25 in total. Last week, students had the opportunity to attend The main event of the Celebration was an ,all day the annual SBU Celebration of Undergraduate Research poster presentation session where students and faculty and Creativity. The event featured the work of students. were able to see type of research that goes on across involved in undergraduate research as well as activities campus all throughout the year. Some of the other in the arts. According to a recent press release issued by featured events included symposia held concurrently Karen Kernan, the Director of Programs for Research and by the Departments of English, History, and Psychology Creative Activity (as a part of the Office of the Provost), involving student oral presentations. Also,the College there were over 225 abstracts compiled in this year's. of Engineering and Applied Sciences held its annual book of Collected Abstracts. senior design conference comprising the two best senior the day's events to a close, the purpose and scope of the These 225 project descriptions represented over 300 design projects from each of the four major engineer- Celebration of Undergraduate and Creative Activities undergraduates in the various departments of"Anesthe- ing departments, Biomedical Engineering, Electrical was clear. -

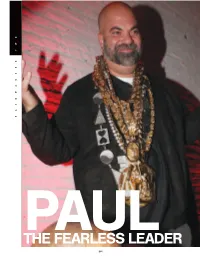

The Fearless Leader Fearless the Paul 196

TWO RAINMAKERS PAUL THE FEARLESS LEADER 196 ven back then, I was taking on far too many jobs,” Def Jam Chairman Paul Rosenberg recalls of his early career. As the longtime man- Eager of Eminem, Rosenberg has been a substantial player in the unfolding of the ‘‘ modern era and the dominance of hip-hop in the last two decades. His work in that capacity naturally positioned him to seize the reins at the major label that brought rap to the mainstream. Before he began managing the best- selling rapper of all time, Rosenberg was an attorney, hustling in Detroit and New York but always intimately connected with the Detroit rap scene. Later on, he was a boutique-label owner, film producer and, finally, major-label boss. The success he’s had thus far required savvy and finesse, no question. But it’s been Rosenberg’s fearlessness and commitment to breaking barriers that have secured him this high perch. (And given his imposing height, Rosenberg’s perch is higher than average.) “PAUL HAS Legendary exec and Interscope co-found- er Jimmy Iovine summed up Rosenberg’s INCREDIBLE unique qualifications while simultaneously INSTINCTS assessing the State of the Biz: “Bringing AND A REAL Paul in as an entrepreneur is a good idea, COMMITMENT and they should bring in more—because TO ARTISTRY. in order to get the record business really HE’S SEEN healthy, it’s going to take risks and it’s going to take thinking outside of the box,” he FIRSTHAND told us. “At its height, the business was run THE UNBELIEV- primarily by entrepreneurs who either sold ABLE RESULTS their businesses or stayed—Ahmet Ertegun, THAT COME David Geffen, Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert FROM ALLOW- were all entrepreneurs.” ING ARTISTS He grew up in the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, surrounded on all sides TO BE THEM- by music and the arts. -

Rapparen & Gourmetkocken Action Bronson Tillbaka Med Nytt Album

2015-03-03 10:31 CET Rapparen & gourmetkocken Action Bronson tillbaka med nytt album Hiphoparen och kocken Arian Asllani, aka Action Bronson, från Queens New York släpper nya albumet Mr. Wonderful den 25 mars. Bronson har med flertalet album, EP’s och mixtapes i ryggen gjort sig ett namn som en utav vår tids bästa rappare. Det sätt han levererar sitt artisteri och kombinerar sina rapfärdigheter med humor, självdistans och genomgående matreferenser gör honom unik i musikvärlden. Innan Bronson påbörjade sin karriär som rappare, som ursprungligen endast var en hobby för honom, var han en respekterad gourmetkock i New York City. Han drev sin egen online matlagnings show med titeln "Action In The Kitchen". Efter att han bröt benet i köket bestämde han sig för att enbart koncentrera sig på musiken. Debutalbumet Dr. Lecter släpptes 2011 såväl som ett par mixtapes, däribland Blue Chips. Sent år 2012 signade rapparen med Warner Music via medieföretaget VICE och för två år sedan släppte han EP’n Saaab Stories samt spelade på en av världens viktigaste musikfestivaler, nämligen Coachella Music Festival. Genom åren har han haft samarbeten med flera stor rappare såsom Wiz Khalifa, Raekwon, Eminem och Kendrick Lamar. Enligt Bronson är det kommande albumet hans bästa verk hittills. “I gave this my most incredible effort,” säger han. “If you listen to everything I’ve put out and then listen to this you’ll hear the steps that I’ve taken to go all out and show progression.” Singeln Baby Blue ft. Chance The Rapper, producerad av Mark Ronson, premiärspelades igår av Zane Lowe på BBC Radio 1. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Ivan Lins: Um “Ator Móvel” Na MPB Dos Anos 1970

Revista Brasileira de Estudos da Canção – ISSN 2238-1198 Natal, v.1, n.1, jan-jun 2012. Disponível em: www.rbec.ect.ufrn.br Ivan Lins: um “ator móvel” na MPB dos anos 1970 Thaís Lima Nicodemo16 [email protected] Resumo: O tema central do presente artigo é a produção do compositor Ivan Lins entre os anos 1970 e o início dos anos 1980. Ao longo desse período sua trajetória passou por significativas transformações, que trazem à tona contradições e conflitos, demarcando a atuação de um artista em busca de seu espaço, mediado pelas relações de mercado. Nos discos de Ivan Lins lançados nesse período, é possível notar uma frequente mudança de estilos musicais e do conteúdo poético das letras, que revelam a maneira como se ajustou à dinâmica da indústria cultural, assim como às transformações nos planos político, ideológico e econômico, durante a década de 1970, no Brasil. Palavras-chave: MPB; anos 1970; Ivan Lins. Abstract: The main subject of this paper is the production of songwriter Ivan Lins from the 1970s to the beginning of the 1980s. Throughout this period his career underwent significant changes, which bring about contradictions and conflicts, showing an artist’s search for his own ground, a process mediated by market relations. In his albums from this period, one notes a frequent shift in musical style and in the poetic contents of the lyrics, which reveal the way by which he adapted himself to the dynamics of cultural industry, as well as the political, ideological and economical transformations that took place in Brazil in the 1970s. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

Fresh Connect Marketing Plan 2020

Fresh Connect Marketing Plan 2020 Operational Budget: Individual Paid Ads Fresh Connect Week Flier Facebook: A budget of $5.00 per day for 2 weeks (Week: Start Nov. 22nd and Week Nov. 29) - $70.00 Instagram: A budget of $5.00 per day for 30 days (Week: Start Nov. 11) - $150.00 _________________________________________________________ Smaller Ad Placements (Fundraising/Spons placement content) Facebook: A budget of $5.00 per day for 5 days (2 Posts in total) - $50.00 Instagram: A Budget of $5.00 per day for 7 days (2 Posts in total) - $70.00 _________________________________________________________ Graphic Designer: Logo and additional expenses for fliers - $220.00 Physical Posters (Digital Printing Center) 30 Posters (8x11 or 11x17) - Waiting on the center to reach out Total: $560.00 Platform Daily Price Duration Total Days Posts Total Week Flier Facebook $5 Nov22 - 14 $70 Dec 5 Instagram $5 Nov11 - 30 $150 Dec 10 Smaller Ad Facebook $5 5 2 $50 Placements Instagram $5 7 2 $70 Unit Price Amount Total Logo $100 1 $100 Graphic Designer Flyer $30 3 $120 Physical Posters 30 In Total: $560 EVENT / CONTENT Calendar: FOR THE MONTH OF NOVEMBER Funding proposal documentation must include (but is not limited to) the following: Team Objectives ● Objective 1: Increase the amount of social interaction we get on social media by utilizing ads and interactions. We hope to raise Facebook's followers up to 700 from 243 and Instagram from 176 to 500 by December 7th. ● Objective 2: To market as many artists as we can through proposals, video interactions and articles. We will showcase each featured artist twice a week on Facebook and Instagram closer to the programming(2-3 weeks before December 7th). -

Smifnwessun Jeru 17.12.11 DRESDEN Pressetext

krasscore concerts presents SMIF N WESSUN & JERU THA DAMAJA „90ies Rap X-Mas Special pt.2“ date: Sa. 17.12.2011 venue: Scheune Alaunstr. 36/40 01099 Dresden acts: Smif N Wessun (Brooklyn / NYC) Jeru tha Damaja (Brooklyn / NYC) special: AFTER-SHOW-PARTY mit DJ Access (New DEF / Dresden) Einlass: 21:00 Beginn: 22:00 Eintritt: 18 € im VVK (incl. After-Show-Party!) ohne Gebühren: in allen Harlem Stores, Supreme, Titus und Späti (Striesen) zzgl. VVK-Geb.: VVK bundesweit an allen VVK-Stellen, online unter www.krasscore.com/tickets und in Dresden z.B. bei Dresden Ticket, KoKa Florentinum & Schillergalerie allen SZ-Treffpunkten (Altmarktgalerie, Elbe Park, Karstadt, Seidnitz Center) & Sax-Ticket www.krasscore.com Seit 2001 kümmert sich die Crew von krasscore concerts um die Belange der Rap-Fans in Dresden & Umgebung. Seit letztem Jahr ist es nun fast schon Tradition, dass sich alle Ami-Rap Fans am letzten Samstag vor Weihnachten auf ein Highlight in dieser Sparte freuen können. Denn am 17.12. werden nach Group Home, Dilated Peoples, Lootpack, Black Milk, Sean Price, Brand Nubian, Camp Lo, Das EFX, Masta Ace und vielen anderen amerikanischen Rap- Größen endlich auch SMIF N WESSUN die Bühne der Scheune rocken - und das zum ersten Mal überhaupt in Dresden! Um die Sache richtig abzurunden, konnte der ebenfalls aus Brooklyn stammende JERU THA DAMAJA gewonnen werden, der nach über neun Jahren Pause Dresden erneut beehren wird. Und da Weihnachten nun mal die Zeit der Geschenke ist, möchte sich das Team von krasscore bei allen Gästen für die teilweise jahrelange Treue bedanken, weshalb die Karten für das X-mas-HipHop-Spektakel im Supreme & den Harlem Stores lediglich 18 Euro kosten. -

Gravediggaz 6 Feet Deep Mp3, Flac, Wma

Gravediggaz 6 Feet Deep mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: 6 Feet Deep Country: US Style: Horrorcore MP3 version RAR size: 1839 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1113 mb WMA version RAR size: 1634 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 977 Other Formats: AHX WAV AU WMA FLAC MP4 VOC Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Just When You Thought It Was Over (Intro) 0:10 2 Constant Elevation 2:28 3 Nowhere To Run, Nowhere To Hide 3:54 4 Defective Trip (Trippin') 5:04 5 2 Cups Of Blood 1:26 Blood Brothers 6 4:47 Producer – Gatekeeper 360 Questions 7 Vocals [Voice] – Amier, Derrick Lovelace, Djinji Brown, Eddie Berkley*, Hellrazor*, Tracey 0:33 Witherspoon, Vernon Reid 1-800 Suicide 8 4:17 Bass [Bass Guitar] – Scott "The Moleman" Harding* Diary Of A Madman 9 4:34 Co-producer – Prince PaulFeaturing – Killah Priest, Scientific Shabazz*Producer – RNS Mommy, What's A Gravedigga? 10 1:44 Bass – Scott Harding 11 Bang Your Head 3:23 Here Comes The Gravediggaz 12 3:44 Producer – Mr. Sime Graveyard Chamber 13 4:56 Featuring – Dreddy Kruger, Killah Priest, Scientific Shabazz* Deathtrap 14 2:57 Keyboards – Don NewkirkVoice – Masta Ace 6 Feet Deep 15 4:36 Producer – Gravediggaz 16 Rest In Peace (Outro) 2:00 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Island Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Island Records Ltd. Licensed To – Island Records Inc. Manufactured For – BMG Direct Marketing, Inc. – D 106000 Credits Producer – Prince Paul (tracks: 1 to 5, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16), RZA (tracks: 9, 13, 15) Scratches, Mixed By, Other [Overseen By] – Prince Paul Notes © 1994 Island Records Ltd.