Massimiliano L. Delfino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema

The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema Ekky Imanjaya Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies December 2016 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Abstract Classic Indonesian exploitation films (originally produced, distributed, and exhibited in the New Order’s Indonesia from 1979 to 1995) are commonly negligible in both national and transnational cinema contexts, in the discourses of film criticism, journalism, and studies. Nonetheless, in the 2000s, there has been a global interest in re-circulating and consuming this kind of films. The films are internationally considered as “cult movies” and celebrated by global fans. This thesis will focus on the cultural traffic of the films, from late 1970s to early 2010s, from Indonesia to other countries. By analyzing the global flows of the films I will argue that despite the marginal status of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films become the center of a taste battle among a variety of interest groups and agencies. The process will include challenging the official history of Indonesian cinema by investigating the framework of cultural traffic as well as politics of taste, and highlighting the significance of exploitation and B-films, paving the way into some findings that recommend accommodating the movies in serious discourses on cinema, nationally and globally. -

Latvian Neorealism in the Films of Laila Pakalniņa

BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2016 / VOLUME 4 / ARTICLE Article Alternative Networks of Globalisation: Latvian Neorealism in the Films of Laila Pakalniņa KLĀRA BRŪVERIS, University of New South Wales, Australia; email: [email protected] 38 DOI: 10.1515/bsmr-2017-0003 BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2016 / VOLUME 4 / ARTICLE ABSTRACT This paper examines the development of neorealist tendencies in the oeuvre of contemporary Latvian filmmaker Laila Pakalnina. Her work is positioned within the global dissemination of cinematic neorealism, and its local manifestations, which, it is argued, develop in specific national contexts in reaction to dramatic societal and political changes. Pakalniņa’s films are examined as a documentation of the change from a communist satellite state to an independent democratic, capitalist country. Heavily influenced by the Riga School of Poetic Documentary, a movement in Latvian cinema that adhered to the conventions of poetic documentary filmmaking, the article analyses how her films replicate and further develop the stylistic and aesthetic devices of the Italian neorealists and the succeeding cinematic new waves. In doing so the argument is put forth that Pakalnina has developed neorealism Latvian style. Due to their size, small nations do not pos- grassroots globalisation is also occurring in sess the economic or political capital to Latvia. More specifically, the Latvian direc- participate in dominant networks of globali- tor Laila Pakalniņa is participating in an sation, which serve the interests of larger, alternative network of cinema globalisation wealthier nations that use global networks by re-appropriating the stylistic and aes- for political or financial gain (Hjort, Petrie thetic tropes of Italian neorealism, which 2007: 8). -

Thea Supervisor

Constructions of Cinematic Space: Spatial Practice at the Intersection of Film and Theory by Brian R. Jacobson B.S. Computer Science Appalachian State University, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTSINSTTTIJTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2005 AUG 18 2005 I I LIBRARtF F3., C 2005 Brian R. Jacobson. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: ,epartment of Comparative Media Studies August 1, 2005 Certified by: , '/ 0%1111-- - V./ V William Uricchio Professor and Co-Director of Comparative Mania Studies / TheAHer Supervisorekn Accepted by: I .My ,/t Henry Jenkins III Professor and Co-Director ¢jtomparative Media Studies .ARCHIVES >.-M- Constructions of Cinematic Space: Spatial Practice at the Intersection of Film and Theory by Brian R. Jacobson Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on August 1, 2005 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT This thesis is an attempt to bring fresh insights to current understandings of cinematic space and the relationship between film, architecture, and the city. That attempt is situated in relation to recent work by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Saskia Sassen, and others on the importance of the city in the current global framework, along with the growing body of literature on film, architecture, and urban space. -

The Cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele

WHO IS BEHIND THE CAMERA? The cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele Silvana Tuccio Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2009 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Who is behind the camera? Abstract The cinema of independent film director Giorgio Mangiamele has remained in the shadows of Australian film history since the 1960s when he produced a remarkable body of films, including the feature film Clay, which was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. This thesis explores the silence that surrounds Mangiamele’s films. His oeuvre is characterised by a specific poetic vision that worked to make tangible a social reality arising out of the impact with foreignness—a foreign society, a foreign country. This thesis analyses the concept of the foreigner as a dominant feature in the development of a cinematic language, and the extent to which the foreigner as outsider intersects with the cinematic process. Each of Giorgio Mangiamele’s films depicts a sharp and sensitive picture of the dislocated figure, the foreigner apprehending the oppressive and silencing forces that surround his being whilst dealing with a new environment; at the same time the urban landscape of inner suburban Melbourne and the natural Australian landscape are recreated in the films. As well as the international recognition given to Clay, Mangiamele’s short films The Spag and Ninety-Nine Percent won Australian Film Institute awards. Giorgio Mangiamele’s films are particularly noted for their style. This thesis explores the cinematic aesthetic, visual style and language of the films. -

Italian Neo-Realism Italian Nation Film School Created by Facists 1935-Run by Mussolini’S Son

Italian Neo-Realism Italian Nation Film School created by Facists 1935-run by Mussolini’s son. Cinecetta Studios (Hollywood on the Tiber)-1937 Begins: Rome, Open City (filmed between 43-45) - Roberto Rossellin 1945 (makes Paisan 1946) Ends: Umberto D- De Sica (1952) Most Popular Films: Ladri di biciclette (aka Bicycle Thieves) (1948) Sciuscià (aka ShoeShine) (1946) 1) Movement is characterized by stories set amongst the poor and working class. Neorealist films generally feature children in major roles, though their roles are frequently more observational than participatory. Based on real or “composite” events. 2) Brought about in part, by end of Facism, poverty, destruction at end of WWII. 3) Semi-documentary Styles: a. Long takes, natural light, Location Shooting, Non-professional actors, Naturalistic Costumes, makeup, sets. b. Lack of Artiface c. Camera angles from normal perspectives d. Less Dominant Musical Scores 4) Dubbing of dialogue. The dubbing allowed for filmmakers to move in a more open mise-en-scene. 5) Filmed in long takes and almost exclusively on location, mostly in poor neighborhoods and in the countryside. Frequently using non-actors for secondary and sometimes primary roles. (though, in a number of cases, well known actors were cast in leading roles, playing strongly against their normal character types in front of a background populated by local people rather than extras brought in for the film). 6) Italian neorealist films mostly contend with the difficult economical and moral conditions of postwar Italy, reflecting the changes in the Italian psyche and the conditions of everyday life: defeat, poverty, and desperation. 7) A blending of Christian and Marxist humanism, with emphasis on the value of ordinary people . -

Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected]

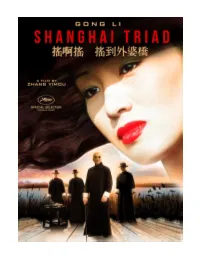

presents a film by ZHANG YIMOU starring GONG LI LI BAOTIAN LI XUEJIAN SUN CHUN WANG XIAOXIAO ————————————————————— “Visually sumptuous…unforgettable.” –New York Post “Crime drama has rarely been this gorgeously alluring – or this brutal.” –Entertainment Weekly ————————————————————— 1995 | France, China | Mandarin with English subtitles | 108 minutes 1.85:1 Widescreen | 2.0 Stereo Rated R for some language and images of violence DIGITALLY RESTORED Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Jimmy Weaver | Theatrical | (216) 704-0748 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Hired to be a servant to pampered nightclub singer and mob moll Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), naive teenager Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao) is thrust into the glamorous and deadly demimonde of 1930s Shanghai. Over the course of seven days, Shuisheng observes mounting tensions as triad boss Tang (Li Baotian) begins to suspect traitors amongst his ranks and rivals for Xiao Jinbao’s affections. STORY Shanghai, 1930. Mr. Tang (Li Boatian), the godfather of the Tang family-run Green dynasty, is the city’s overlord. Having allied himself with Chiang Kai-shek and participated in the 1927 massacre of the Communists, he controls the opium and prostitution trade. He has also acquired the services of Xiao Jinbao (Gong Li), the most beautiful singer in Shanghai. The story of Shanghai Triad is told from the point of view of a fourteen-year-old boy, Shuisheng (Wang Xiaoxiao), whose uncle has brought him into the Tang Brotherhood. His job is to attend to Xiao Jinbao. -

I Cento Passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) Is Giordana's Biopic About Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a Leftist Anti-Mafia Activist Murdered in Sicily in 1978

33 Marco Tullio Giordana' s The Hundred Steps: The Biopic as Political Cinema GEORGE DE STEFANO During the 1980s, the political engagement that fuelled much of Italy's postwar realist cinema nearly vanished, a casualty of both the domin ance of television and the decline of the political Left. The generation of great postwar auteurs - Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, and Pier Paolo Pasolini - had disappeared. Their departure, notes Millicent Marcus, was followed by 'the waning of the ideological and generic impulses that fueled the revolutionary achievement of their successors: Rosi, Petri, Bertolucci, Bellocchio, Ferreri, the Tavianis, Wertmuller, Cavani, and Scola.' 1 The decline of political cinema was inextricable from the declining fortunes of the Left following the vio lent extremism of the 1970s, the so-called leaden years and, a decade later, the fall of Communism. The waning of engage cinema continued throughout the 1990s, with a few exceptions. But as the twentieth cen tury drew to a close, the director Marco Tullio Giordana made a film that represented a return to the tradition of political commitment. I cento passi (The Hundred Steps, 2000) is Giordana's biopic about Giuseppe 'Peppino' Impastato, a leftist anti-Mafia activist murdered in Sicily in 1978. The film was critically acclaimed, winning the best script award at the Venice Film Festival and acting awards for two of its stars. It was a box office success in Italy, with its popularity extending beyond the movie theatres. Giordana's film, screened in schools and civic as sociations throughout Sicily, became a consciousness-raising tool for anti-Mafia forces, as well as a memorial to a fallen leader of the anti Mafia struggle. -

Experiences of Flânerie and Cityscapes in Italian Postwar Film

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks STROLLING THE STREETS OF MODERNITY: EXPERIENCES OF FLÂNERIE AND CITYSCAPES IN ITALIAN POSTWAR FILM TORUNN HAALAND Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of French and Italian, Indiana University OCTOBER 2007 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee Distinguished Professor Emeritus Peter Bondanella Professor Andrea Ciccarelli, Rudy Professor Emeritus James Naremore, Professor Massimo Scalabrini September 24 2007 ii © 2007 Torunn Haaland ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For Peter – for all the work, for all the fun iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thanks go to the members of my dissertation committee, who all in their own way inspired the direction taken in this study while crucially contributing with acute observations and suggestions in its final stages. Even more significant was however the distinct function each of them came to have in encouraging my passion for film and forming the insight and intellectual means necessary to embark on this project in the first place. Thanks to Andrea for being so revealingly lucid in his digressions, to Jim for asking the questions only he could have thought of, to Massimo for imposing warmheartedly both his precision and encyclopaedic knowledge, and thanks to Peter for never losing faith in this or anything else of what he ever made me do. Thanks to my brother Vegard onto whom fell the ungrateful task of copyediting and converting my rigorously inconsistent files. -

Italian Neorealism, Vittorio De Sica, and Bicycle Thieves

CHAPTER 4 ITALIAN NEOREALISM, VITTORIO DE SICA, AND BICYCLE THIEVES The post-World War II birth or creation of neorealism was anything but a collective theoretical enterprise—the origins of Italian neorealist cinema were far more complex than that. Generally stated, its roots were political, in that neorealism reacted ideologically to the control and censorship of the prewar cinema; aesthetic, for the intuitive, imaginative response of neorealist directors coincided with the rise or resurgence of realism in Italian literature, particularly the novels of Italo Calvino, Alberto Moravia, Cesare Pavese, Elio Vittorini, and Vasco Pratolini (a realism that can be traced to the veristic style first cultivated in the Italian cinema between 1913 and 1916, when films inspired by the writings of Giovanni Verga and others dealt with human problems as well as social themes in natural settings); and economic, in that this new realism posed basic solutions to the lack of funds, of functioning studios, and of working equipment. Indeed, what is sometimes overlooked in the growth of the neorealist movement in Italy is the fact that some of its most admired aspects sprang from the dictates of postwar adversity: a shortage of money made shooting in real locations an imperative choice over the use of expensive studio sets, and against such locations any introduction of the phony or the fake would appear glaringly obvious, whether in the appearance of the actors or the style of the acting. It must have been paradoxically exhilarating for neorealist filmmakers to be able to stare unflinchingly at the tragic spectacle of a society in shambles, its values utterly shattered, after years of making nice little movies approved by the powers that were within the walls of Cinecittà. -

Thatcher Alle Corde Sgrida Martelli Eliache Svanisce La Minaccia Militare

Giornale + Salvagente L. 1500 Giornale Anno 67°, n. 105 Spedizione m abb. post. gr. 1/70 del Partito arretrati L. 3300 comunista T'Unita italiano 5 maggio 1990 La dottrina Bush: «Una Nato I laburisti col 43% (+11%) sorpassano i conservatori (31%) che perdono 12 punti Bobbio e Occhietto perplessi più politica* Avanzata tory solo in alcuni distretti londinesi. Annunciato un minirimpasto di governo sul verdetto contro Loto continua «C li Stati Uniti devono restare una potenza europea nel sen- sc più ampio, dal punto di vista politico, militare ed econo mici:». Bush (nella foto) teme che gli Usa vengano tagliati fuori dal processo di unificazione europea, per questo rilan- Andreotti cii II vertice "costituente»della Nato, in programma perfine pijgno. L'Alleanza atlantica - dice il presidente - deve •prendere in considerazione la sua futura missione politica» Thatcher alle corde sgrida Martelli eliache svanisce la minaccia militare. A PAGINA 5 In autostrada Ci si avvia alla fine delle lun ghe ed estenuami code nei con il Telepass caselli delle autostrade? Da sul caso Sofri peir evitare lunedi sull'Autosole, a Mila La destra battuta nel suo «tempio» no, a Roma e a Napoli, in via li! lunghe code sperimentale, va in funzione il Telepass, un sistema tele Per i conservatori è stato un autentico tracollo. Martelli sconfessalo da Andreotti. Sul caso Sofri scen malico che consente all'au- C'è anche Nelle amministrative di giovedì i tories sono calati de in campo il presidente del Consiglio per criticare il tcmobilista di entrare ed uscire senza fermare il veicolo. Il del 12% rispetto al risultato ottenuto nelle ultime suo vice e polemizzare con «quel mondo culturale percorso ed il pedaggio viene registrato attraverso un appa elezioni politiche tre anni fa. -

Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´Y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha)

Journal of Film Preservation Contributors to this issue... Ont collaboré à ce numéro... Journal Han participado en este número... 73 04/2007 ANTTI ALANEN of Film Head of the FIAF Programming and Access to KAE ISHIHARA Collections Commission, Programmer at the Finnish Film Archive Film archivist, Head of Film Preservation Society (Helsinki) (Tokyo) Preservation RENÉ BEAUCLAIR JEANICK LE NAOUR Directeur de la Médiathèque Guy L. Côté, Responsable de la Cinémathèque Afrique (Paris) Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) ÉRIC LE ROY EILEEN BOWSER Chef du Service accès, valorisation et Film historian, Honorary Member of FIAF (New enrichissement des collections, Archives York) françaises du film-CNC (Bois d’Arcy) PAOLO CHERCHI USAI PATRICK LOUGHNEY Director, National Film and Sound Archive Senior Curator, George Eastman House - Motion (Canberra) Picture Department (Rochester) Revista de la Federación Internacional de Archivos Fílmicos JOSÉ MANUEL COSTA NWANNEKA OKONKWO Film archivist, Cinemateca portuguesa / Museo Head of the do cinema (Lisbon) National Film Video and Sound Archive (Jos) ROBERT DAUDELIN VLADIMIR OPELA Rédacteur en chef du Journal of Film Preservation Director and Curator, Národní Filmov´y Archiv (Montréal) (Praha) MARCO DE BLOIS PAULO EMILIO SALLES GOMES the by Published International Federation of Film Archives Conservateur cinéma d’animation, Film scholar and archivist (1929 -1977) (São Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) Paulo) CHRISTIAN DIMITRIU ROGER SMITHER Éditeur et membre du comité de rédaction du Keeper, Film and Video -

Neorealism: What Is and Is Not

PART I Neorealism: What Is and Is Not Creating their works out of the ruins of World War II, authors and fi lm- makers such as Primo Levi, Alberto Moravia, and Vittorio De Sica attracted international acclaim for their elaboration of neorealism as the aesthetic defi ning post-Fascist, or “new,” Italy. Although not a formalized artistic school with prescriptive tenets, Italian neorealism became noted for its literary and cinematic focus on stories that arose from the everyday lives of common people during Fascism, the Nazi occupation, World War II, and the immediate postwar period. Generally viewed as fl ourishing from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s, the movement broadened signifi cantly during the 1960s and 1970s as several authors and directors returned to the original themes of neorealism. 1 The neorealist movement has been associated primarily with leftist intel- lectuals who hoped that “communism or a more egalitarian form of gov- ernment would eventually prevail” in Italy after the defeat of Fascism to “transform Italian society” (Pastina 86). Thus, these artists renounced the rhetorical fl ourishes generally associated with the Fascist regime (1922– 1942) and fashioned a documentary style, describing the often brutal material conditions of postwar Italy in simple, colloquial language. They devoted substantial attention to social, economic, and political problems, giving rise to the concept of impegno sociale , or the “social commitment” of artists to renewing Italy and its citizens. 2 Neorealism made it possible to express emotions, realities, and problems previously camoufl aged by the Fascists (Leprohon). Theorists have attrib- uted the international success of Italian neorealism to “the compassion of its products,” as authors and fi lmmakers created “poignant syntheses 10 NEOREALISM AND THE “NEW” ITALY of the anguish experienced by a whole nation” (Pacifi ci 241).