Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who's Who at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1939)

W H LU * ★ M T R 0 G 0 L D W Y N LU ★ ★ M A Y R MyiWL- * METRO GOLDWYN ■ MAYER INDEX... UJluii STARS ... FEATURED PLAYERS DIRECTORS Astaire. Fred .... 12 Lynn, Leni. 66 Barrymore. Lionel . 13 Massey, Ilona .67 Beery Wallace 14 McPhail, Douglas 68 Cantor, Eddie . 15 Morgan, Frank 69 Crawford, Joan . 16 Morriss, Ann 70 Donat, Robert . 17 Murphy, George 71 Eddy, Nelson ... 18 Neal, Tom. 72 Gable, Clark . 19 O'Keefe, Dennis 73 Garbo, Greta . 20 O'Sullivan, Maureen 74 Garland, Judy. 21 Owen, Reginald 75 Garson, Greer. .... 22 Parker, Cecilia. 76 Lamarr, Hedy .... 23 Pendleton, Nat. 77 Loy, Myrna . 24 Pidgeon, Walter 78 MacDonald, Jeanette 25 Preisser, June 79 Marx Bros. —. 26 Reynolds, Gene. 80 Montgomery, Robert .... 27 Rice, Florence . 81 Powell, Eleanor . 28 Rutherford, Ann ... 82 Powell, William .... 29 Sothern, Ann. 83 Rainer Luise. .... 30 Stone, Lewis. 84 Rooney, Mickey . 31 Turner, Lana 85 Russell, Rosalind .... 32 Weidler, Virginia. 86 Shearer, Norma . 33 Weissmuller, John 87 Stewart, James .... 34 Young, Robert. 88 Sullavan, Margaret .... 35 Yule, Joe.. 89 Taylor, Robert . 36 Berkeley, Busby . 92 Tracy, Spencer . 37 Bucquet, Harold S. 93 Ayres, Lew. 40 Borzage, Frank 94 Bowman, Lee . 41 Brown, Clarence 95 Bruce, Virginia . 42 Buzzell, Eddie 96 Burke, Billie 43 Conway, Jack 97 Carroll, John 44 Cukor, George. 98 Carver, Lynne 45 Fenton, Leslie 99 Castle, Don 46 Fleming, Victor .100 Curtis, Alan 47 LeRoy, Mervyn 101 Day, Laraine 48 Lubitsch, Ernst.102 Douglas, Melvyn 49 McLeod, Norman Z. 103 Frants, Dalies . 50 Marin, Edwin L. .104 George, Florence 51 Potter, H. -

December 2016 Calendar

December Calendar Exhibits In the Karen and Ed Adler Gallery 7 Wednesday 13 Tuesday 19 Monday 27 Tuesday TIMNA TARR. Contemporary quilting. A BOB DYLAN SOUNDSWAP. An eve- HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free AFTERNOON ON BROADWAY. Guys and “THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY” (2015- December 1 through January 2. ning of clips of Nobel laureate Bob blood pressure screening conducted Dolls (1950) remains one of the great- 108 min.). Writer/director Matt Brown Dylan. 7:30 p.m. by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. est musical comedies. Frank Loesser’s adapted Robert Kanigel’s book about music and lyrics find a perfect match pioneering Indian mathematician Registrations “THE DRIFTLESS AREA” (2015-96 min.). in Damon Runyon-esque characters Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) and Bartender Pierre (Anton Yelchin) re- and a New York City that only exists in his friendship with his mentor, Profes- In progress turns to his hometown after his parents fantasy. Professor James Kolb discusses sor G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons). Stephen 8 Thursday die, and finds himself in a dangerous the show and plays such unforgettable Fry co-stars as Sir Francis Spring, and Resume Workshop................December 3 situation involving mysterious Stella songs as “A Bushel and a Peck,” “Luck Be Jeremy Northam portrays Bertrand DIRECTOR’S CUT. Film expert John Bos- Entrepreneurs Workshop...December 3 (Zoe Deschanel) and violent crimi- a Lady” and “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ Russell. 7:30 p.m. co will screen and discuss Woody Al- Financial Checklist.............December 12 nal Shane (John Hawkes). Directed by the Boat.” 3 p.m. -

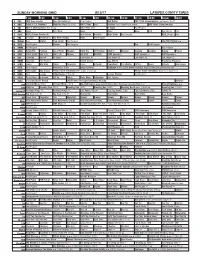

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

Raymond Burr

Norma Shearer Biography Norma Shearer was born on August 10, 1902, in Montreal's upper-middle class Westmount area, where she studied piano, took dance lessons, and learned horseback riding as a child. This fortune was short lived, since her father lost his construction company during the post-World War I Depression, and the Shearers were forced to leave their mansion. Norma's mother, Edith, took her and her sister, Athole, to New York City, hoping to get them into acting. They stayed in an unheated boarding house, and Edith found work as a sales clerk. When the odd part did come along, it was small. Athole was discouraged, but Norma was motivated to work harder. A stream of failed auditions paid off when she landed a role in 1920's The Stealers. Arriving in Los Angeles in 1923, she was hired by Irving G. Thalberg, a boyish 24-year- old who was production supervisor at tiny Louis B. Mayer Productions. Thalberg was already renowned for his intuitive grasp of public taste. He had spotted Shearer in her modest New York appearances and urged Mayer to sign her. When Mayer merged with two other studios to become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, both Shearer and Thalberg were catapulted into superstardom. In five years, Shearer, fueled by a larger-than-life ambition, would be a Top Ten Hollywood star, ultimately becoming the glamorous and gracious “First Lady of M-G-M.” Shearer’s private life reflected the poise and elegance of her onscreen persona. Smitten with Thalberg at their first meeting, she married him in 1927. -

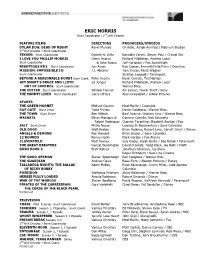

ERIC NORRIS Stunt Coordinator / 2Nd Unit Director

ERIC NORRIS Stunt Coordinator / 2nd Unit Director FEATURE FILMS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS DYLAN DOG: DEAD OF NIGHT Kevin Munroe Gil Adler, Ashok Amritraj / Platinum Studios 2nd Unit Director / Stunt Coordinator TEKKEN Stunt Coordinator Dwight H. Little Benedict Carver, Steven Paul / Crystal Sky I LOVE YOU PHILLIP MORRIS Glenn Ficarra Richard Middleton, Andrew Lazar Stunt Coordinator & John Requa Jeff Harlacker / Fox Searchlight RIGHTEOUS KILL Stunt Coordinator Jon Avnet Rob Cowan, Emmett/Furla Films / Overture MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE III J.J. Abrams Tom Cruise, Paula Wagner Stunt Coordinator Stratton Leopold / Paramount BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT Stunt Coord. Peter Hyams Kevin Cornish, Ted Hartley GET SMART’S BRUCE AND LLOYD Gil Junger Richard Middleton, Andrew Lazar OUT OF CONTROL Stunt Coordinator Warner Bros. THE CUTTER Stunt Coordinator William Tannen Avi Lerner, Trevor Short / Sony THE MUMMY LIVES Stunt Coordinator Gerry O’Hara Allan Greenblatt / Global Pictures STUNTS THE GREEN HORNET Michael Gondry Neal Moritz / Columbia DUE DATE Stunt Driver Todd Phillips Daniel Goldberg / Warner Bros. THE TOWN Stunt Driver Ben Affleck Basil Iwanyk, Graham King / Warner Bros. MACHETE Ethan Maniquis & Dominic Cancilla, Rick Schwartz Robert Rodriguez Quentin Tarantino, Elizabeth Avellan / Fox SALT Stunt Driver Phillip Noyce Lorenzo Di Bonaventura / Sony Columbia OLD DOGS Walt Becker Brian Robbins, Robert Levy, Garrett Grant / Disney ANGELS & DEMONS Ron Howard Brian Grazer / Sony Columbia 12 ROUNDS Renny Harlin Mark Gordon / Fox Atomic CLOVERFIELD Matt Reeves Guy Riedel, Bryan Burke / Bad Robot / Paramount THE GREAT DEBATERS Denzel Washington David Crockett, Todd Black, Joe Roth / MGM RUSH HOUR 3 Brett Ratner Jonathan Glickman, Jay Stern Roger Birnbaum / New Line Cinema THE GOOD GERMAN Steven Soderbergh Ben Cosgrove / Warner Bros. -

The Sopranos Episode Guide Imdb

The sopranos episode guide imdb Continue Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 200102 200204 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Edit It's time for the annual ecclera and, as usual, Pauley is responsible for the 5 day affair. It's always been a money maker for Pauley - Tony's father, Johnny Soprano, had control over him before him - but a new parish priest believes that the $10,000 Poly contributes as the church's share is too low and believes $50,000 would be more appropriate. Pauley shies away from that figure, at least in part, he says, because his own spending is rising. One thing he does to save money to hire a second course of carnival rides, something that comes back to haunt him when one of the rides breaks down and people get injured. Pauley is also under a lot of stress after his doctor dislikes the results of his PSA test and is planning a biopsy. When Christopher's girlfriend Kelly tells him he is pregnant, he asks her to marry him. He is still struggling with his addiction however and falls off the wagon. Written by GaryKmkd Plot Summary: Add a Summary Certificate: See All The Certificates of the Parents' Guide: Add Content Advisory for Parents Edit Vic Noto plays one of the bikies from the Vipers group that Tony and Chris steal wine from. -

The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman in July

CORE © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016. This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyeditMetadata, version of citation a chapter and published similar papers in at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive Lasting Screen Stars: Images that Fade and Personas that Endure. The final authenticated version is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40733-7_6 ‘What Price Widowhood?’: The Faded Stardom of Norma Shearer Lies Lanckman In July 1934, Photoplay magazine featured an article entitled ‘The Real First Lady of Film’, introducing the piece as follows: The First Lady of the Screen – there can be only one – who is she? Her name is not Greta Garbo, or Katharine Hepburn, not Joan Crawford, Ruth Chatterton, Janet Gaynor or Ann Harding. It’s Norma Shearer (p. 28). Originally from Montréal, Canada, Norma Shearer signed her first MGM contract at age twenty. By twenty-five, she had married its most promising producer, Irving Thalberg, and by thirty-five, she had been widowed through the latter’s untimely death, ultimately retiring from the screen forever at forty. During the intervening twenty years, Shearer won one Academy Award and was nominated for five more, built up a dedicated, international fan base with an active fan club, was consistently featured in fan magazines, and starred in popular and critically acclaimed films throughout the silent, pre-Code and post-Code eras. Shearer was, at the height of her fame, an institution; unfortunately, her career is rarely as well-remembered as those of her contemporaries – including many of the stars named above. -

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida

Boca Raton, Florida 1 Boca Raton, Florida City of Boca Raton — City — Downtown Boca Raton skyline, seen northwest from the observation tower of the Gumbo Limbo Environmental Complex Seal Nickname(s): A City for All Seasons Location in Palm Beach County, Florida Coordinates: 26°22′7″N 80°6′0″W Country United States State Florida County Palm Beach Settled 1895 Boca Raton, Florida 2 Incorporated (town) May, 1925 Government - Type Commission-manager - Mayor Susan Whelchel (N) Area - Total 29.1 sq mi (75.4 km2) - Land 27.2 sq mi (70.4 km2) - Water 29.1 sq mi (5.0 km2) Elevation 13 ft (4 m) Population - Total 86396 ('06 estimate) - Density 2682.8/sq mi (1061.7/km2) Time zone EST (UTC-5) - Summer (DST) EDT (UTC-4) ZIP code(s) Area code(s) 561 [1] FIPS code 12-07300 [2] GNIS feature ID 0279123 [3] Website www.ci.boca-raton.fl.us Boca Raton (pronounced /ˈboʊkə rəˈtoʊn/) is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, USA, incorporated in May 1925. In the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 74,764; the 2006 population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 86,396.[4] However, the majority of the people under the postal address of Boca Raton, about 200,000[5] in total, are not actually within the City of Boca Raton's municipal boundaries. It is estimated that on any given day, there are roughly 350,000 people in the city itself.[6] In terms of both population and land area, Boca Raton is the largest city between West Palm Beach and Pompano Beach, Broward County. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

The Wire the Complete Guide

The Wire The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 29 Jan 2013 02:03:03 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 The Wire 1 David Simon 24 Writers and directors 36 Awards and nominations 38 Seasons and episodes 42 List of The Wire episodes 42 Season 1 46 Season 2 54 Season 3 61 Season 4 70 Season 5 79 Characters 86 List of The Wire characters 86 Police 95 Police of The Wire 95 Jimmy McNulty 118 Kima Greggs 124 Bunk Moreland 128 Lester Freamon 131 Herc Hauk 135 Roland Pryzbylewski 138 Ellis Carver 141 Leander Sydnor 145 Beadie Russell 147 Cedric Daniels 150 William Rawls 156 Ervin Burrell 160 Stanislaus Valchek 165 Jay Landsman 168 Law enforcement 172 Law enforcement characters of The Wire 172 Rhonda Pearlman 178 Maurice Levy 181 Street-level characters 184 Street-level characters of The Wire 184 Omar Little 190 Bubbles 196 Dennis "Cutty" Wise 199 Stringer Bell 202 Avon Barksdale 206 Marlo Stanfield 212 Proposition Joe 218 Spiros Vondas 222 The Greek 224 Chris Partlow 226 Snoop (The Wire) 230 Wee-Bey Brice 232 Bodie Broadus 235 Poot Carr 239 D'Angelo Barksdale 242 Cheese Wagstaff 245 Wallace 247 Docks 249 Characters from the docks of The Wire 249 Frank Sobotka 254 Nick Sobotka 256 Ziggy Sobotka 258 Sergei Malatov 261 Politicians 263 Politicians of The Wire 263 Tommy Carcetti 271 Clarence Royce 275 Clay Davis 279 Norman Wilson 282 School 284 School system of The Wire 284 Howard "Bunny" Colvin 290 Michael Lee 293 Duquan "Dukie" Weems 296 Namond Brice 298 Randy Wagstaff 301 Journalists 304 Journalists of The Wire 304 Augustus Haynes 309 Scott Templeton 312 Alma Gutierrez 315 Miscellany 317 And All the Pieces Matter — Five Years of Music from The Wire 317 References Article Sources and Contributors 320 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 324 Article Licenses License 325 1 Overview The Wire The Wire Second season intertitle Genre Crime drama Format Serial drama Created by David Simon Starring Dominic West John Doman Idris Elba Frankie Faison Larry Gilliard, Jr. -

September 8, 2009 (XIX:2) Raoul Walsh HIGH SIERRA (1941, 100 Min)

September 8, 2009 (XIX:2) Raoul Walsh HIGH SIERRA (1941, 100 min) Directed by Raoul Walsh Screenplay by John Huston and W.R. Burnett Cinematography by Tony Gaudio Ida Lupino...Marie Humphrey Bogart...Roy Earle Alan Curtis...'Babe' Arthur Kennedy...'Red' Joan Leslie...Velma Henry Hull...'Doc' Banton Henry Travers...Pa Jerome Cowan...Healy Minna Gombell...Mrs. Baughmam Barton MacLane...Jake Kranmer Elisabeth Risdon...Ma Cornel Wilde...Louis Mendoza George Meeker...Pfiffer Zero the Dog...Pard RAOUL WALSH (11 March 1887, NYC—31 December 1980, Simi Valley, CA), directed 136 films, the last of which was A Distant Trumpet (1964). Some of the others were The Naked and the Dead (1958), Band of Angels (1957), The King and Four Queens (1956), officials they kept it under lock and key for 25 years because they Battle Cry (1955), Blackbeard, the Pirate (1952), Along the Great were convinced that if the American public saw Huston’s scenes of Divide (1951), Captain Horatio Hornblower R.N.(1951), White American soldiers crying and suffering what in those days was Heat (1949), Cheyenne (1947), The Horn Blows at Midnight called “shellshock” and “battle fatigue” they would have an even (1945), They Died with Their Boots On (1941), High Sierra more difficult time getting Americans to go off and get themselves (1941), They Drive by Night (1940), The Roaring Twenties (1939), killed in future wars. One military official accused Huston of being Sadie Thompson (1928), What Price Glory (1926), Thief of “anti-war,” to which he replied, “If I ever make a pro-war film I Baghdad (1924), Evangeline (1919), Blue Blood and Red (1916), hope they take me out and shoot me.” During his long career he The Fatal Black Bean (1915), Who Shot Bud Walton? (1914) and made a number of real dogs e.g. -

FOREST LAWN MEMORIAL PARK Hollywood Hills Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills

Welcome to FOREST LAWN MEMORIAL PARK Hollywood Hills Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Order of Service Waltzing Matilda Played by the Forest Lawn Organist – Anthony Zediker Eulogy to be read by Jack. L. Warner Pall Bearers, To be Announced. Photo by Tony Duran Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Photo by Tony Duran Orry George Kelly December 31, 1897 - February 27, 1964 Forest Lawn Memorial Park Hollywood Hills Orry-Kelly Filmography 1963 Irma la Douce 1942 Always in My Heart (gowns) 1936 Isle of Fury (gowns) 1963 In the Cool of the Day 1942 Kings Row (gowns) 1936 Cain and Mabel (gowns) 1962 Gypsy (costumes designed by) 1942 Wild Bill Hickok Rides (gowns) 1936 Give Me Your Heart (gowns) 1962 The Chapman Report 1942 The Man Who Came to Dinner (gowns) 1936 Stage Struck (gowns) 1962 Five Finger Exercise 1941 The Maltese Falcon (gowns) 1936 China Clipper (gowns) (gowns: Miss Russell) 1941 The Little Foxes (costumes) 1936 Jailbreak (gowns) 1962 Sweet Bird of Youth (costumes by) 1941 The Bride Came C.O.D. (gowns) 1936 Satan Met a Lady (gowns) 1961 A Majority of One 1941 Throwing a Party (Short) 1936 Public Enemy’s Wife (gowns) 1959 Some Like It Hot 1941 Million Dollar Baby (gowns) 1936 The White Angel (gowns) 1958 Auntie Mame (costumes designed by) 1941 Affectionately Yours (gowns) 1936 Murder by an Aristocrat (gowns) 1958 Too Much, Too Soon (as Orry Kelly) 1941 The Great Lie (gowns) 1936 Hearts Divided (gowns)